Cutaneous Lymphomas and Sarcoma

Epidemiology and Etiology

Age of Onset. Median age at diagnosis 55–60 years.

Sex. Male:female ratio 2:1.

Incidence. Uncommon but not rare.

Etiology. Unknown. CTCL is a malignancy of skin-homing CTLA+ CD4+ T cells.

Clinical Manifestations

For months to years, often preceded by various diagnoses such as psoriasis, nummular dermatitis, and “large plaque” parapsoriasis. Symptoms: pruritus, often intractable, but may be none.

Skin Findings. Skin lesions are classified into patches, plaques, and tumors. Patients may have simultaneously more than one type of lesions.

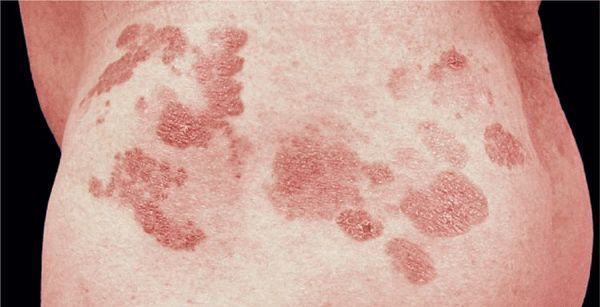

Patches. Randomly distributed, scaling or non-scaling patches in different shades of red (Fig. 21-3). Well- or ill-defined; at first superficial, much like eczema or psoriasis (Figs. 21-3 and 21-4) or mimicking dermatophytosis (“mycosis”), and later becoming thicker.

Figure 21-3. Mycosis fungoides In early stages, lesions consist of randomly distributed, well-, and/or ill-defined patches and later plaques as shown here in a 37-year-old male. They may be scaly and appear in various shades of red. They mimic eczema, psoriasis, or dermatophytosis.

Figure 21-4. Mycosis fungoides: patches/plaque stage More advanced stages show confluence of patches and plaques with irregular configuration. This patient had been treated unsuccessfully for psoriasis for 2 years. Morphologically, he could also have extensive, confluent dermatophytosis (see Section 26), but a negative KOH preparation ruled out this diagnosis. Only after a biopsy had been done was the correct diagnosis of MF made.

Plaques. Round, oval, but often also arciform, annular, and of bizarre configuration (Figs. 21-3 and 21-5). Lesions are randomly distributed but in early stages often spare exposed areas.

Figure 21-5. Mycosis fungoides Plaque and early nodular stage with reddish-brownish scaly, and crusted plaques and flat nodules.

Tumors. Later lesions consist of nodules (Figs. 21-5 and 21-6) and tumors, with or without ulceration (Fig. 21-7). Extensive infiltration can cause leonine facies (Fig. 21-8). Confluence may lead to erythroderma (see Section 8). There is palmoplantar keratoderma and there may be hair loss. Poikiloderma may be present from the onset or develop later (Fig. 21-9).

Figure 21-6. Mycosis fungoides: tumor stage Scaly and crusted eczema-like plaques seen on the arm and chest have turned nodular on the shoulder. This patient had similar lesions elsewhere and was staged IIB (T3 N1 M0).

Figure 21-7. Mycosis fungoides: tumors Two large ulcerated tumors on the lower leg of 58-year-old man. These lesions indeed look like mushrooms.

Figure 21-8. Mycosis fungoides: leonine facies In this 50-year-old patient, the disease had started with extremely pruritic, generalized eczema-like plaques on the trunk that had been treated as eczema over a course of 4 years. Massive nodular infiltration of the face occurred only recently leading to a leonine facies.

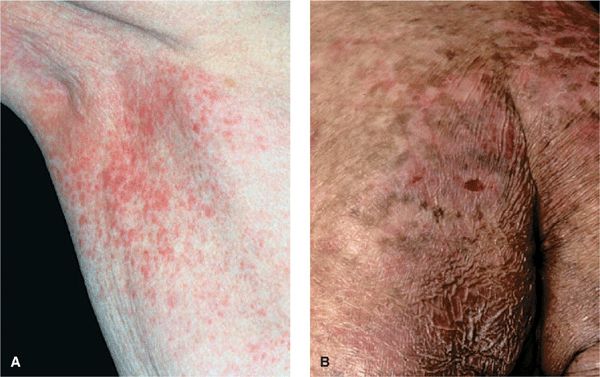

Figure 21-9. Mycosis fungoides: poikilodermatous lesions (A) Small reticulated, confluent papules mixed with superficial atrophy give the impression of poikiloderma. This patient had patches elsewhere on the body similar to those shown in Fig. 20-3. (B) Poikiloderma in MF can also result from treatment. This patient had been treated with electron beam.

General Examination. Lymphadenopathy, usually after thick plaques and nodules have appeared.

Laboratory Examinations

Dermatopathology. Bandlike and patchy infiltrate in upper dermis of atypical lymphocytes (mycosis cells) extending to epidermis and skin appendages. The classic finding is the epidermotropism of this T cell infiltrate, which will form microabscesses in the epidermis (Pautrier microabscesses). In the plaque and tumor stage, the infiltrate extends deep into the dermis and beyond. Mycosis cells are T cells with hyper-chromatic, irregularly shaped (cerebriform) nuclei. Mitoses vary from rare to frequent.

Mycosis cells are activated monoclonal CTLA+ CD4+ T cells. However, lesions of MF often have a CD8+ T cell component, and these cells are considered to reflect an antitumor response.

Hematology. Eosinophilia, 6–12%, can increase to 50%. Buffy coat: abnormal circulating T cells (mycosis cell-type) and increased WBC (20,000/μL). Bone marrow examination is not helpful in early stages.

Chemistry. Lactic dehydrogenase isoenzymes 1, 2, and 3 increased in erythrodermic stage.

Chest X-Ray. Search for hilar lymphadenopathy.

Imaging. In stage I and stage II disease, diagnostic imaging (CT, gallium scintigraphy, liver–spleen scan, and lymphangiography) does not provide more information than biopsies of lymph nodes.

CT Scan. With more advanced disease, to search for retroperitoneal nodes in patients with extensive skin involvement, lymphadenopathy.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

In the early stages, the diagnosis of MF is a problem. Clinical lesions may be typical, but histologic confirmation may not be possible for years despite repeated biopsies. Immunophenotyping of infiltrating T cells by use of monoclonal antibodies and T cell receptor rearrangement studies. Lymphadenopathy and the detection of abnormal circulating T cells in the blood appear to correlate well with internal organ involvement.

Differential Diagnosis. Mainly scaling plaques. High index of suspicion is needed in patients with atypical or refractory “psoriasis,” “eczema,” and poikiloderma. MF often mimics psoriasis in being a scaly plaque and disappearing with exposure to sunlight.

Patient Evaluation in MF and Staging. This has to focus on an evaluation of tumor burden, the degree of atypia of malignant cells, and the state of immunocompetence of the patient. Table 21-1 shows a flow sheet of patient evaluation, and Table 21-2 shows the TNM classification and staging of MF.

TABLE 21-1 PATIENT EVALUATION IN MF

TABLE 21-2 TNM STAGING OF MYCOSIS FUNGOIDES

Course and Prognosis

Unpredictable; MF (pre-MF) may be present for years. Course varies with the source of the patients studied. At the NIH, there was a median survival time of 5 years from the time of the histologic diagnosis, while in Europe a less malignant course is seen (survival time, up to 10–15 years). This, however, may be due to patient selection. Prognosis is much worse when (1) tumors are present (mean survival, 2.5 years), (2) there is lymphadenopathy (mean survival, 3 years), (3) >10% of the skin surface is involved with pretumor-stage MF, and (4) there is a generalized erythroderma. Patients <50 years have twice the survival rate of patients >60 years.

Management

Therapy is symptom-oriented and extent of disease- and stage-adapted. In the pre-MF stage, in which the histologic diagnosis is only compatible, but not confirmed, PUVA photochemo-therapy or narrowband UVB treatment is most effective. For histologically proven plaque-stage disease with no lymphadenopathy and no abnormal circulating T cells, PUVA photochemotherapy is also the method of choice, either alone or combined with oral isotretinoin or bexarotene or subcutaneous interferon-α. Also used at this stage are topical chemotherapy with nitrogen mustard in an ointment base (10 mg/dL), topical carmustine (BCNU) (for limited body surface area involvement), and total-body electron-beam therapy, singly or in combination. Isolated tumors are treated with local x-ray or electron-beam therapy. For extensive plaque stage with multiple tumors or in patients with lymphadenopathy or abnormal circulating T cells, electron-beam plus chemotherapy is probably the best combination for now; randomized, controlled studies of various combinations are in progress. Also, extracorporeal PUVA photochemotherapy is being evaluated in patients with Sézary syndrome.

Cutaneous lymphomas are clonal proliferations of neoplastic T or B cells, rarely natural killer cells or plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Cutaneous lymphomas are the second most common group of extranodal lymphomas. The annual incidence is estimated to be 1 per 100,000.

Cutaneous lymphomas are clonal proliferations of neoplastic T or B cells, rarely natural killer cells or plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Cutaneous lymphomas are the second most common group of extranodal lymphomas. The annual incidence is estimated to be 1 per 100,000. For rare conditions not dealt with in this Atlas, the reader is referred to Beyer M, Sterry W. Cutaneous lymphoma. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:1745-1782.

For rare conditions not dealt with in this Atlas, the reader is referred to Beyer M, Sterry W. Cutaneous lymphoma. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:1745-1782. ICD-10: C83/E88

ICD-10: C83/E88

Adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) is a neoplasm of CD4+/CD25+ T cells, caused by human T cell lymphotrophic virus I (HTLV-I).

Adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) is a neoplasm of CD4+/CD25+ T cells, caused by human T cell lymphotrophic virus I (HTLV-I). Manifested by skin infiltrates, hypercalcemia, visceral involvement, lytic bone lesions, and abnormal lymphocytes on peripheral smears.

Manifested by skin infiltrates, hypercalcemia, visceral involvement, lytic bone lesions, and abnormal lymphocytes on peripheral smears. HTLV-I is a human retrovirus. Infection by the virus does not usually cause disease, which suggests that other environmental factors are involved. Immortalization of some infected CD4+ T cells, increased mitotic activity, genetic instability, and impairment of cellular immunity can all occur after infection with HTLV-I. These events may increase the probability of additional genetic changes, which, by chance, may lead to the development of leukemia 20–40 years after infection in some people (<5%). Most of these effects have been attributed to the HTLV-I-encoded protein tax.

HTLV-I is a human retrovirus. Infection by the virus does not usually cause disease, which suggests that other environmental factors are involved. Immortalization of some infected CD4+ T cells, increased mitotic activity, genetic instability, and impairment of cellular immunity can all occur after infection with HTLV-I. These events may increase the probability of additional genetic changes, which, by chance, may lead to the development of leukemia 20–40 years after infection in some people (<5%). Most of these effects have been attributed to the HTLV-I-encoded protein tax. ATLL occurs in southwestern Japan (Kyushu), Africa, the Caribbean Islands, and southeastern United States. Transmission is by sexual intercourse, perinatally, or by exposure to blood or blood products (same as HIV).

ATLL occurs in southwestern Japan (Kyushu), Africa, the Caribbean Islands, and southeastern United States. Transmission is by sexual intercourse, perinatally, or by exposure to blood or blood products (same as HIV). There are four main categories. In the relatively indolent smoldering and chronic forms, the median survival is >2 years. In the acute and lymphomatous forms, it ranges from only 4 to 6 months.

There are four main categories. In the relatively indolent smoldering and chronic forms, the median survival is >2 years. In the acute and lymphomatous forms, it ranges from only 4 to 6 months. Symptoms include fever, weight loss, abdominal pain, diarrhea, pleural effusion, ascites, cough, and sputum. Skin lesions occur in 50% of patients with ATLL. Single to multiple small, confluent erythematous, violaceous papules (

Symptoms include fever, weight loss, abdominal pain, diarrhea, pleural effusion, ascites, cough, and sputum. Skin lesions occur in 50% of patients with ATLL. Single to multiple small, confluent erythematous, violaceous papules (

Patients are seropositive (ELISA, Western blot) to HTLV-I; in IV drug users, up to 30% have dual retroviral infection with both HTLV-I and HIV. WBC ranges from normal to 500,000/μL. Peripheral blood smears show polylobulated lymphocytic nuclei (“flower cells”). Dermatopathology reveals lymphomatous infiltrates composed of many large abnormal lymphocytes, ±giant cells, ±Pautrier microabscesses. There is hypercalcemia–in 25% at time of diagnosis of ATLL and in >50% during clinical course; this is thought to be due to osteoclastic bone resorption.

Patients are seropositive (ELISA, Western blot) to HTLV-I; in IV drug users, up to 30% have dual retroviral infection with both HTLV-I and HIV. WBC ranges from normal to 500,000/μL. Peripheral blood smears show polylobulated lymphocytic nuclei (“flower cells”). Dermatopathology reveals lymphomatous infiltrates composed of many large abnormal lymphocytes, ±giant cells, ±Pautrier microabscesses. There is hypercalcemia–in 25% at time of diagnosis of ATLL and in >50% during clinical course; this is thought to be due to osteoclastic bone resorption. Management consists of various regimens of cytotoxic chemotherapy; the rates of complete response are <30% and responses lack durability, but good results have been obtained with the combination of oral zidovudine and subcutaneous interferon-α in acute and lymphoma-type ATLL patients. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation holds some promise.

Management consists of various regimens of cytotoxic chemotherapy; the rates of complete response are <30% and responses lack durability, but good results have been obtained with the combination of oral zidovudine and subcutaneous interferon-α in acute and lymphoma-type ATLL patients. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation holds some promise. ICD-10: C84.0/C84.1

ICD-10: C84.0/C84.1

Cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) is a term that applies to T cell lymphoma first manifested in the skin, but since the neoplastic process involves the entire lymphoreticular system, the lymph nodes and internal organs become involved in the course of the disease. CTCL is a malignancy of helper T cells (CD4+).

Cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) is a term that applies to T cell lymphoma first manifested in the skin, but since the neoplastic process involves the entire lymphoreticular system, the lymph nodes and internal organs become involved in the course of the disease. CTCL is a malignancy of helper T cells (CD4+). In the classic form of CTCL, called mycosis fungoides (MF), the malignant cells are cutaneous CD4+ cells, but the clinical entity of MF has now been expanded to the spectrum of CTCL including non-MF CTCLs.

In the classic form of CTCL, called mycosis fungoides (MF), the malignant cells are cutaneous CD4+ cells, but the clinical entity of MF has now been expanded to the spectrum of CTCL including non-MF CTCLs. Whereas all MF is CTCL not all CTCLs are MF.

Whereas all MF is CTCL not all CTCLs are MF. Only the classic MF form is discussed here.

Only the classic MF form is discussed here. ICD-10: C84.0/C84.1

ICD-10: C84.0/C84.1

MF is the most common cutaneous lymphoma.

MF is the most common cutaneous lymphoma. Arising in mid-to-late adulthood with male predominance of 2:1.

Arising in mid-to-late adulthood with male predominance of 2:1. A clonal proliferation of skin-homing CTLA+ CD4+ T cells with an admixture of CD8+ T cells (antitumor response).

A clonal proliferation of skin-homing CTLA+ CD4+ T cells with an admixture of CD8+ T cells (antitumor response). Categorized as patch, plaque, or tumor stage.

Categorized as patch, plaque, or tumor stage. Related features are pruritus, alopecia, palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, and bacterial infections.

Related features are pruritus, alopecia, palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, and bacterial infections. Histologically, epidermotropism of T cells with hyperconvoluted nuclei. In the tumor stage dermal nodular infiltrates.

Histologically, epidermotropism of T cells with hyperconvoluted nuclei. In the tumor stage dermal nodular infiltrates. Prognosis related to stage.

Prognosis related to stage. Treatment: symptom-oriented and stage-adapted.

Treatment: symptom-oriented and stage-adapted.