Skin Signs of Hematologic Disease

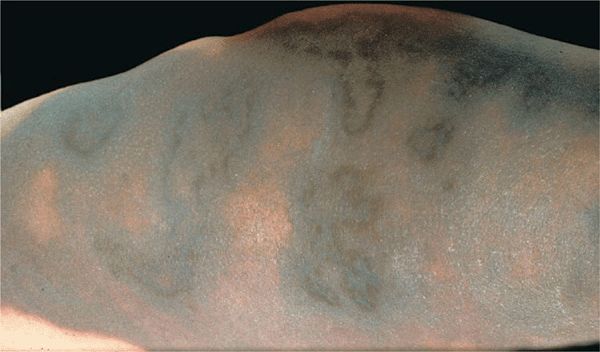

Figure 20-1. Thrombocytopenic purpura Multiple petechiae on the upper arm of an HIV-infected 25-year-old male were the presenting manifestation of his disease. The linear arrangement of petechiae at the site of minor trauma is called vibices.

Figure 20-2. Thrombocytopenic purpura Can first manifest on the oral mucosa or conjunctiva. Here, multiple petechial hemorrhages are seen on the palate.

Epidemiology

Age of Onset. All ages; occurs in children.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

• Events that initiate DIC: Tumor products, crushing trauma, extensive surgery, severe intracranial damage; retained contraception products, placental abruption, amniotic fluid embolism; certain snake bites; hemolytic transfusion reaction; acute promyelocytic leukemia.

• Extensive destruction of endothelial surfaces: Vasculitis in Rocky Mountain spotted fever, meningococcemia, or occasionally gram-negative septicemia; group A streptococcal infection, heat stroke, malignant hyperthermia; extensive pump oxygenation (repair of aortic aneurysm); eclampsia, preeclampsia; tufted angioma and Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: Kasabach–Merritt syndrome; immune complexes; postvaricella purpura gangrenosa.

• Events that complicate and propagate DIC: Shock, complement pathway activation.

Uncontrolled activation of coagulation results in thrombosis and consumption of platelets/clotting factors II, V, and VIII. Secondary fibrinolysis. If the activation occurs slowly, excess activated products are produced, predisposing to vascular infarctions/venous thrombosis. If the onset is acute, hemorrhage surrounding wound sites and IV lines/catheters or bleeding into deep tissues.

Clinical Manifestation

Hours to days; rapid evolution. Fever, chills associated with onset of hemorrhagic lesions.

Skin Lesions. Infarction (purpura fulminans) (Figs. 20-3–20-5): massive ecchymoses with sharp, irregular (“geographic”) borders with deep purple to blue color (Fig. 20-5) and erythematous halo, ± evolution to hemorrhagic bullae (Fig. 20-3), and blue to black gangrene (Fig. 20-5); multiple lesions are often symmetric; distal extremities, areas of pressure; lips, ears, nose, trunk; peripheral acrocyanosis followed by gangrene on hands, feet, tip of nose, with subsequent autoamputation if patient survives.

Figure 20-3. Disseminated intravascular coagulation: purpura fulminans Extensive geographic area of cutaneous infarction with hemorrhage involving the hand. Similar lesions were on the face, the other hand, and the feet.

Figure 20-4. Extensive cutaneous infarction with hemorrhage involving the entire leg This catastrophic event followed sepsis after abdominal surgery.

Figure 20-5. Disseminated intravascular coagulation: purpura fulminans Geographic cutaneous infarctions on the chest; lesions were also present on the hands, elbows, thighs, and feet. The patient was a diabetic with Staphylococcus aureus sepsis.

Hemorrhage from multiple cutaneous sites, i.e., surgical incisions, venipuncture, or catheter sites.

Mucous Membranes. Hemorrhage from gingiva.

General Examination. High fever, tachycardia, ± shock. Multitude of findings depending on the associated medical/surgical problem.

Laboratory Examinations

Dermatopathology. Occlusion of arterioles with fibrin thrombi. Dense PMN infiltrate around infarct and massive hemorrhage.

Hematologic Studies. CBC. Schistocytes (fragmented RBCs), arising from RBC entrapment and damage within fibrin thrombi, seen on blood smear; platelet count low. Leukocytosis.

Coagulation Studies. Reduced plasma fibrinogen; elevated fibrin degradation products; prolonged prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and thrombin time.

Blood Culture. For bacterial sepsis.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Clinical suspicion confirmed by coagulation studies. Differential diagnosis of large cutaneous infarctions: necrosis after initiation of warfarin therapy, heparin necrosis, calciphylaxis, atheroembolization.

Course and Prognosis

Mortality rate is high. Surviving patients require skin grafts or amputation for gangrenous tissue. Common complications: severe bleeding, thrombosis, tissue ischemia/necrosis, hemolysis, organ failure.

Management

Vigorous antibiotic therapy for infections. Control bleeding or thrombosis: heparin, pent-oxifylline, protein C concentrate.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Type I Cryoglobulins: Monoclonal immunoglobulins (IgM, IgG, IgA, light chains). Associated with plasma cell dyscrasias such as multiple myeloma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, lymphoproliferative disorders such as B cell lymphoma.

Type II Cryoglobulins: Mixed cryoglobulins: two immunoglobulin components, one of which is monoclonal (usually IgG, less often IgM) and the other polyclonal; components interact and cryoprecipitate. Associated with multiple myeloma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome.

Type III Cryoglobulins: Polyclonal immunoglobulins that form cryoprecipitate with polyclonal IgG or a nonimmunoglobulin serum component occasionally mixed with complement and lipoproteins. Represents immune complex disease. Associated with autoimmune diseases; connective tissue diseases; wide variety of infectious diseases, i.e., hepatitis B, hepatitis C, Epstein–Barr virus infection, cytomegalovirus infection, subacute bacterial endocarditis, leprosy, syphilis, streptococcal infections.

Clinical Manifestation

There is cold sensitivity in <50% of cases. Chills, fever, dyspnea, and diarrhea may occur following cold exposure. Purpura also may follow long periods of standing or sitting. Due to other organ system involvement, arthralgia, renal symptoms, neurologic symptoms, abdominal pain, arterial thrombosis.

• Noninflammatory purpura (usually type I), occurring at cold-exposed sites, e.g., helix (Fig. 20-6), tip of nose.

Figure 20-6. Cryoglobulinemia: monoclonal (type I) This noninflamed, purpuric lesion on the helix appeared on the first cold day in the fall.

• Acrocyanosis and Raynaud phenomenon, with or without severe resultant gangrene of fingertips and toes or elsewhere on arms or legs (usually type I or II) (Fig. 20-7).

Figure 20-7. Cryoglobulinemia: mixed (type II) (A) Extensive necrosis and hemorrhage on the skin of the forearm. There was also digital gangrene on hands and feet. (B) Extensive hemorrhagic necrosis on both legs. There was also acral gangrene on four toes.

• Palpable purpura with bullae and necroses (usually types II and III) due to hypersensitivity vasculitis, occurring in crops on lower extremities with extension to thighs, abdomen; precipitated by standing up (Fig. 20-8), less commonly by cold.

• Livedo reticularis mostly on lower and upper extremities.

Figure 20-8. Cryoglobulinemia: polyclonal (type III) Palpable purpura with widespread hemorrhagic blisters and necrosis as in any other type of hypersensitivity vasculitis (compare with Fig. 14-57). Patient had diabetes and amputation of several toes.

• Urticaria induced by cold, associated with purpura.

• Systemic involvement: Between 30% and 60% of individuals with essential mixed CG (type II) develop renal disease with hypertension, edema, or renal failure. Neurologic involvement manifests as peripheral sensorimotor polyneuropathy, presenting as paresthesias or foot drop. Arthritis. Hepatosplenomegaly.

• Diagnosis is confirmed by determination of cryoglobulins (blood drawn into warmed syringe, RBC removed via warmed centrifuge; plasma refrigerated in a Wintrobe tube at 4°C for 24–72 h, then centrifuged and cryocrit determined) and diagnosis of underlying disease.

• The course is characterized by cyclic eruptions induced by cold or fluctuations of the activity of the underlying disease.

• Treatment is that of the underlying disease.

ICD-10: D69.3

ICD-10: D69.3

Thrombocytopenic purpura (TP) is characterized by cutaneous hemorrhages occurring in association with a reduced platelet count.

Thrombocytopenic purpura (TP) is characterized by cutaneous hemorrhages occurring in association with a reduced platelet count. Occur at sites of minor trauma/pressure (platelet count <40,000/μL) or spontaneously (platelet count <10,000/μL).

Occur at sites of minor trauma/pressure (platelet count <40,000/μL) or spontaneously (platelet count <10,000/μL). Due to decreased platelet production, splenic sequestration, or increased platelet destruction.

Due to decreased platelet production, splenic sequestration, or increased platelet destruction. Decreased platelet production. Direct injury to bone marrow, drugs (cytosine arabinoside, daunorubicin, cyclophosphamide, busulfan, methotrexate, 6-mercaptopurine, vinca alkaloids, thiazide diuretics, ethanol, estrogens), replacement of bone marrow, aplastic anemia, vitamin deficiencies, Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome.

Decreased platelet production. Direct injury to bone marrow, drugs (cytosine arabinoside, daunorubicin, cyclophosphamide, busulfan, methotrexate, 6-mercaptopurine, vinca alkaloids, thiazide diuretics, ethanol, estrogens), replacement of bone marrow, aplastic anemia, vitamin deficiencies, Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome. Splenic sequestration. Splenomegaly, hypothermia.

Splenic sequestration. Splenomegaly, hypothermia. Increased platelet destruction. Immunologic: autoimmune TP, drug hypersensitivity (sulfonamides, quinine, quinidine, carbamazepine, digitoxin, methyldopa), after transfusion. Nonimmunologic: infection, prosthetic heart valves, disseminated intravascular coagulation, thrombotic TP.

Increased platelet destruction. Immunologic: autoimmune TP, drug hypersensitivity (sulfonamides, quinine, quinidine, carbamazepine, digitoxin, methyldopa), after transfusion. Nonimmunologic: infection, prosthetic heart valves, disseminated intravascular coagulation, thrombotic TP. Skin Lesions. Petechiae—small (pinpoint to pinhead), red, nonblanching macules that are not palpable and turn brown as they get older (

Skin Lesions. Petechiae—small (pinpoint to pinhead), red, nonblanching macules that are not palpable and turn brown as they get older ( Mucous Membranes. Petechiae—most often on palate (

Mucous Membranes. Petechiae—most often on palate ( General Examination. Possible CNS hemorrhage, anemia.

General Examination. Possible CNS hemorrhage, anemia. Laboratory Hematology. Thrombocytopenia.

Laboratory Hematology. Thrombocytopenia. Serology. Rule out HIV disease.

Serology. Rule out HIV disease. Lesional Skin Biopsy (usually can be controlled by suturing biopsied site) to rule out vasculitis

Lesional Skin Biopsy (usually can be controlled by suturing biopsied site) to rule out vasculitis Differential diagnosis. Senile purpura, purpura of scurvy, progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg disease), purpura following severe Valsalva maneuver (coughing, vomiting/retching), traumatic purpura, factitial or iatrogenic purpura, vasculitis.

Differential diagnosis. Senile purpura, purpura of scurvy, progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg disease), purpura following severe Valsalva maneuver (coughing, vomiting/retching), traumatic purpura, factitial or iatrogenic purpura, vasculitis. Management. Identify underlying cause and correct, if possible. Oral glucocorticoids, high-dose IV immunoglobulins, platelet transfusion, chronic ITP: splenectomy may be indicated.

Management. Identify underlying cause and correct, if possible. Oral glucocorticoids, high-dose IV immunoglobulins, platelet transfusion, chronic ITP: splenectomy may be indicated.

ICD-10: D65

ICD-10: D65

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a widespread blood clotting disorder occurring within blood vessels.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a widespread blood clotting disorder occurring within blood vessels. Associated with a wide range of clinical circumstances: bacterial sepsis, obstetric complications, disseminated malignancy, massive trauma.

Associated with a wide range of clinical circumstances: bacterial sepsis, obstetric complications, disseminated malignancy, massive trauma. Manifested by purpura fulminans (cutaneous infarctions and/or acral gangrene) or bleeding from multiple sites.

Manifested by purpura fulminans (cutaneous infarctions and/or acral gangrene) or bleeding from multiple sites. The spectrum of clinical symptoms associated with DIC ranges from relatively mild and subclinical to explosive and life threatening.

The spectrum of clinical symptoms associated with DIC ranges from relatively mild and subclinical to explosive and life threatening. Synonyms: Purpura fulminans, consumption coagulopathy, defibrination syndrome, coagulation fibrinolytic syndrome.

Synonyms: Purpura fulminans, consumption coagulopathy, defibrination syndrome, coagulation fibrinolytic syndrome. ICD-10: D89.1

ICD-10: D89.1

Cryoglobulinemia (CG) is the presence of serum immunoglobulin (precipitates at low temperature and redissolves at 37°C) complexed with other immunoglobulins or proteins.

Cryoglobulinemia (CG) is the presence of serum immunoglobulin (precipitates at low temperature and redissolves at 37°C) complexed with other immunoglobulins or proteins. Associated clinical findings include purpura in cold-exposed sites, Raynaud phenomenon, cold urticaria, acral hemorrhagic necrosis, bleeding disorders, vasculitis, arthralgia, neurologic manifestations, hepatosplenomegaly, and glomerulonephritis.

Associated clinical findings include purpura in cold-exposed sites, Raynaud phenomenon, cold urticaria, acral hemorrhagic necrosis, bleeding disorders, vasculitis, arthralgia, neurologic manifestations, hepatosplenomegaly, and glomerulonephritis. Precipitation of cryoglobulins (when present in large amounts) causes vessel occlusion, also associated with hyperviscosity.

Precipitation of cryoglobulins (when present in large amounts) causes vessel occlusion, also associated with hyperviscosity. Platelet aggregation/consumption of clotting factors by cryoglobulins, causing coagulation disorder.

Platelet aggregation/consumption of clotting factors by cryoglobulins, causing coagulation disorder. Immune complex deposition followed by complement activation and vasculitis.

Immune complex deposition followed by complement activation and vasculitis.