Granuloma Faciale: Introduction

|

Epidemiology

Early cases of granuloma faciale were reported as “eosinophilic granuloma” of the skin. Weidman was the first to separate three cases that had been previously reported in the literature as variants of erythema elevatum diutinum.1 Lever and Leeper helped to differentiate the lesions from other eosinophil-rich diseases.2 Cobane, Straith, and Pinkus later stressed the histologic resemblance to erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) and termed the lesions “facial granulomas with eosinophilia” and later granuloma faciale.3 Granuloma faciale occurs predominantly in adult men and women. There is a slight male predominance, and mean age at presentation is 52 years.4,5 Granuloma faciale can occur in individuals of any race; however, it is more common in Caucasians. The disease presents most commonly with a single lesion on the face, but extrafacial lesions have been described.6 Patients with multiple lesions have also been reported.7 A rare mucosal variant has been described as eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis, which typically involves the upper respiratory tract.8

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The etiology of granuloma faciale is unknown. The disease can be considered a localized chronic fibrosing vasculitis.9 Immunofluorescence studies have revealed deposition of immunoglobulins and complement factors in the vessel walls consistent with a type III immunologic response, marked by deposition of circulating immune complexes surrounding superficial and deep blood vessels.10,11 However, other authors have described negative results with immunofluorescence.12

Clinical Findings

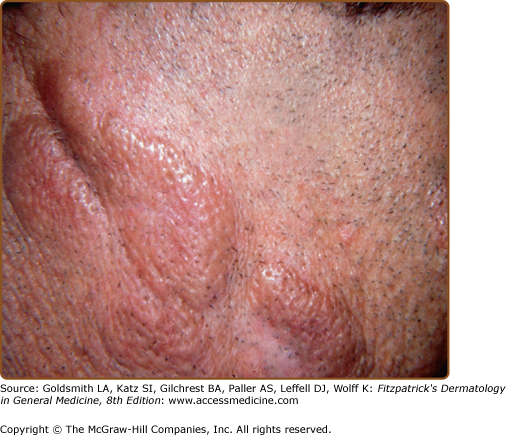

Granuloma faciale is characterized by solitary papules, plaques, or nodules. The lesions are typically asymptomatic red, brown, or violaceous plaques that are soft, smooth, and well circumscribed, often showing follicular accentuation and telangiectasia (Figs. 34-1 and 34-2). Ulceration is rare. Lesions are most common on the face. Sites of predilection include the nose, preauricular area, cheeks, forehead, eyelids, and ears.4,12 Rarely, patients may present with multiple lesions or lesions on the trunk or extremities. Extrafacial lesions have been reported both as isolated findings and in conjunction with facial lesions. Lesions may be present for weeks or months and tend to follow a chronic course. Lesions are typically asymptomatic; however, patients may complain of tenderness, burning, or pruritus.4 Photoexacerbation of lesions has been reported.13

Laboratory Findings

An extensive laboratory evaluation is not required. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is occasionally detected.

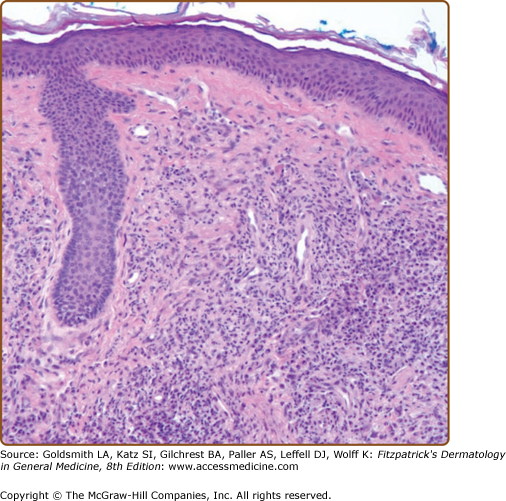

The diagnosis may be established by a combination of clinical findings and confirmatory tissue biopsy results. A punch biopsy that includes the full thickness of the dermis is recommended. Histologic examination shows a normal-appearing epidermis, which may be separated from the underlying inflammatory infiltrate by a narrow grenz zone (Fig. 34-3). Within the dermis is a dense and diffuse infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils with evidence of leukocytoclasis (Fig. 34-4). The inflammatory infiltrate surrounds the blood vessels, which show evidence of fibrin deposition. In later stages, the perivascular fibrin deposition becomes extensive and dominates the histologic picture. Deposition of hemosiderin may contribute to the brown color seen clinically. Electron microscopic studies confirm the presence of an extensive eosinophilic infiltrate with Charcot–Leyden crystals and numerous histiocytes filled with lysosomal vesicles; however, cases with few eosinophils in the infiltrate have also been described.14 Immunoglobulins, fibrin, and complement can be found deposited along the dermal–epidermal junction in a granular pattern and around blood vessels by direct immunofluorescence.10

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnosis for granuloma faciale includes discoid lupus erythematosus, polymorphous light eruption, fixed drug eruption, benign lymphocytic infiltrate of Jessner, lymphoma cutis, pseudolymphoma, sarcoidosis, granuloma annulare, tinea faciei, insect bite reaction, xanthogranuloma, mastocytoma, basal cell carcinoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and rosacea (Box 34-1). The diagnosis can be reliably made by histologic examination. Absence of serologic evidence of lupus erythematosus helps to differentiate these lesions from the lesions of discoid lupus erythematosus.