Cheek

BIOANATOMY AND BIOMECHANICS

The cheek extends medially from the nasolabial fold and nasofacial sulcus laterally to the preauricular sulcus. Superomedially, the cheek ends at the infraorbital crease and laterally at the zygomatic arch. The inferolateral border is the margin of the mandible. The cheek is a convex structure in youth and often develops an inferolateral concavity with age consequent to volume loss. The skin is generally nonsebaceous. In men, the lateral and inferior cheek bares dense terminal hair. In youth, the medial border of the cheek with the upper lip lateral subunit is indistinct, but with age a visible nasolabial fold develops. The nasofacial sulcus is a concave deflection which defines the shape of the nose, and ablation of which leads to asymmetry.

The cheek is not the structure of greatest cosmetic significance on the face and a simple scar on the cheek is not indicative of disfigurement. Nonetheless, large complex scars on the cheek can be very distracting. Grafts are, with few exceptions, unaesthetic and unacceptable. Fortunately, large reconstructions can often be accomplished while maintaining aesthetic goals. Repairs that are designed to avoid the medial cheek are more aesthetically pleasing on frontal view. Because repairs on the cheek are often not anchored by deep restraint, horizontal and vertical tension vectors can be transmitted to free margins. It is important to direct tensions horizontally to avoid lower lid ectropion and to maintain the positions of the infraorbital crease, the alar crease, and the nasolabial fold.

The subcutaneous fatty tissue of the cheek is deep and extensive. Laterally, the fibrous septae of the fat intermingle with the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) as it extends inferiorly from the temple. Medially, the SMAS is much deeper, wrapping the underlying facial musculature. The fat of the medial cheek is particularly thick, thus providing a very mobile base for reconstruction. The superficial fat lobules of the cheek are dense and richly vascularized, especially in middle-aged to older patients with rosacea. The deeper fat lobules are elongated, much larger, and supplied by larger, less-frequent vessels. For this reason, it is far easier to undermine somewhat more deeply within the subcutaneous tissue of the cheek. The laxity available on the cheek is highly variable. Some older patients have loose, redundant skin and even extensive wounds can easily be closed with minimal undermining. In some middle-aged patients with thick, fibrous, highly vascularized cheeks, all reconstructions can be challenging.

The vascular supply of the cheek is highly redundant with multiple perforators and branches from the infraorbital artery, facial artery, and superficial temporal artery.

Neurovascular structures lie deeply in the cheek. The facial artery courses along and usually just lateral to the nasolabial fold. The infraorbital artery emerges deeply from the infraorbital foramen and branches extensively within the deep subcutaneous fat. Laterally, the origin of the superficial temporal artery is deep to the SMAS. The zygomatic and buccal branches of the facial nerve emerge from the anterior surface of the parotid gland along with the parotid duct and run over the surface of the masseter muscle to ramify in the muscles of facial expression. While these structures can be damaged in the extirpation of extensive tumors, they are not generally encountered with surgical reconstruction, which is a more superficial process.

LINEAR REPAIRS

Many wounds of the cheek are elegantly repaired with linear or S-shaped closures, and this approach is often preferable to a flap reconstruction. Literatures on reconstruction frequently note that a broken-up scar on the cheek from a Z-plasty or rhombic flap attracts less attention than a straight line of a similar length.1 This is a debatable point, and while transposition flaps are of great use on the cheek, in many cases nothing is as aesthetic as a well-planned and executed, well-healed linear repair.2

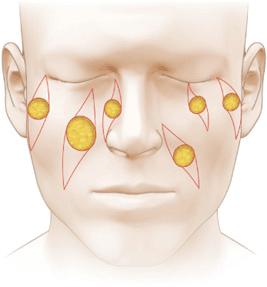

Linear repairs on the cheek are ideally oriented along an off vertical axis coursing from superomedial to inferolateral (Fig. 11.1). Appropriate incision orientations have been well described and lead to aesthetic closures. Near the nasolabial fold and nasofacial sulcus, repairs coursing within the preexisting cosmetic junction are highly aesthetic (Fig. 11.2). Small wounds of the mid-cheek are well repaired with straight lines coursing along the relaxed facial lines. For larger wound of the mid and outer cheek, a lazy S-shaped closure is usually preferable (Fig. 11.3). Fairly broad wounds of the cheek can be repaired linearly (Fig. 11.4). One challenge encountered is that in younger individuals in particular, the cheek is bowed outward in a convex manner. In such patients who retain their natural facial volume, strict linear repairs tend to cause superior and inferior standing tissue cones. Appropriate undermining of the tips and dog-ear revision can be needed, but with time, dog-ears on the cheek do tend to resolve and may not warrant making incisions overly long.

Figure 11.1 Common orientation of linear repairs on the cheek. Medially the repairs often parallel the nasofacial sulcus. When coursing over a convexity, an S-shaped repair may be appropriate

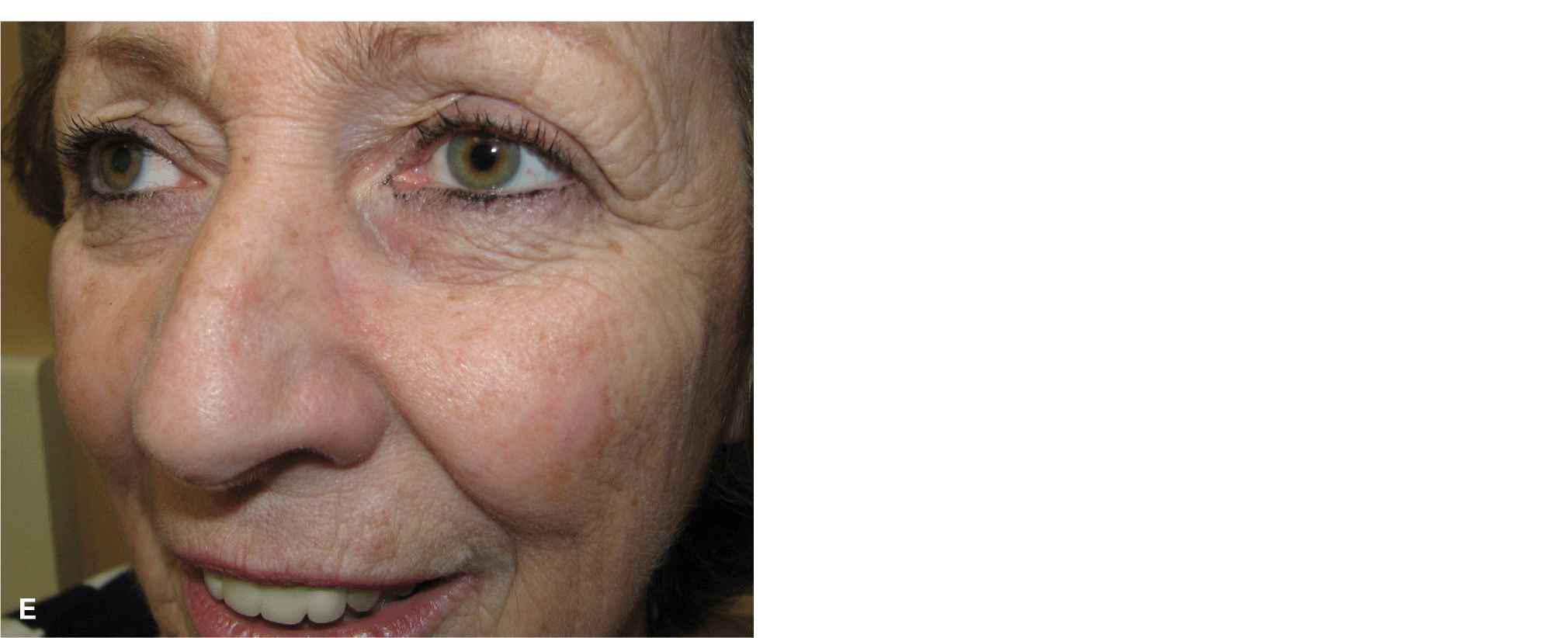

Figure 11.2 Linear repairs of the nasolabial fold and medial cheek. (A) Defect of the medial cheek adjacent to the apical triangle of the lip. (B) The wound is closed side to side along the nasolabial fold and curvilinearly around the ala, preserving the apical triangle. (C) Defect of the medial cheek/lateral nose. (D) Linear repair along the nasofacial sulcus. The junction of the cheek and nose is farther medial than is commonly recognized. (E) Closure at 6 months

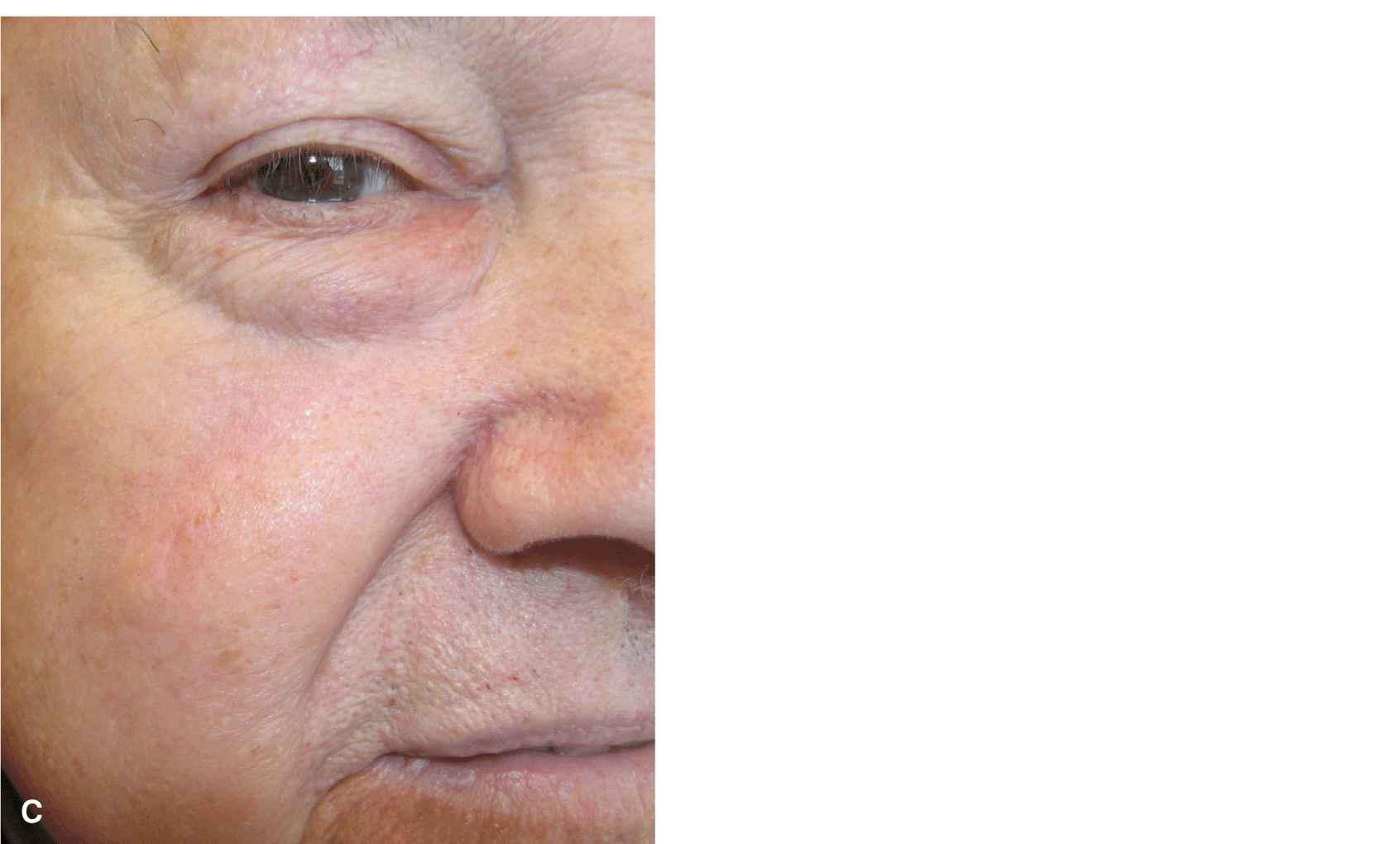

Figure 11.3 S-shaped repair of the mid-cheek. (A) Defect and planned S-shaped closure. (B) Closure follows the natural contour of the face. The upper portion is undermined above orbicularis. The lower portion is undermined in the deeper adipose. (C) Aesthetic closure at 6 months. The S-shaped closure in this area is more natural and may also minimize dog-ear formation

Figure 11.4 Linear closure of larger cheek wounds. (A) Moderate wound on the mid-cheek. (B) Long linear repair. (C) Result at 6 months. (D) Moderate wound on the mid-cheek. (E) Immediate long linear closure

Wounds along the malar eminence pose somewhat of a challenge as they often involve some eyelid skin and also cross over a prominent convexity. In such cases, an S-shaped closure is again very helpful. The upper portion of the repair courses nearly vertical with a slight slant to lateral. The S-portion of the wound jogs laterally at the infraorbital crease, and then the inferior portion of the wound continues in a more vertical fashion inferolaterally. This repair is performed at two planes. The upper portion is performed above orbicularis oculi and the central portion of the repair is separated from the infraorbital crease. The lower portion of the repair is performed in the deeper subcutis.

On the lateral cheek, a convex outwardly bowed repair is often successful. Even though the medial arc of the repair is substantially shorter than the outer arc, the fact that the closure is created over a highly convex surface allows for the tissue mismatch to be sewn out without visible redundancy.

ADVANCEMENT/ROTATION

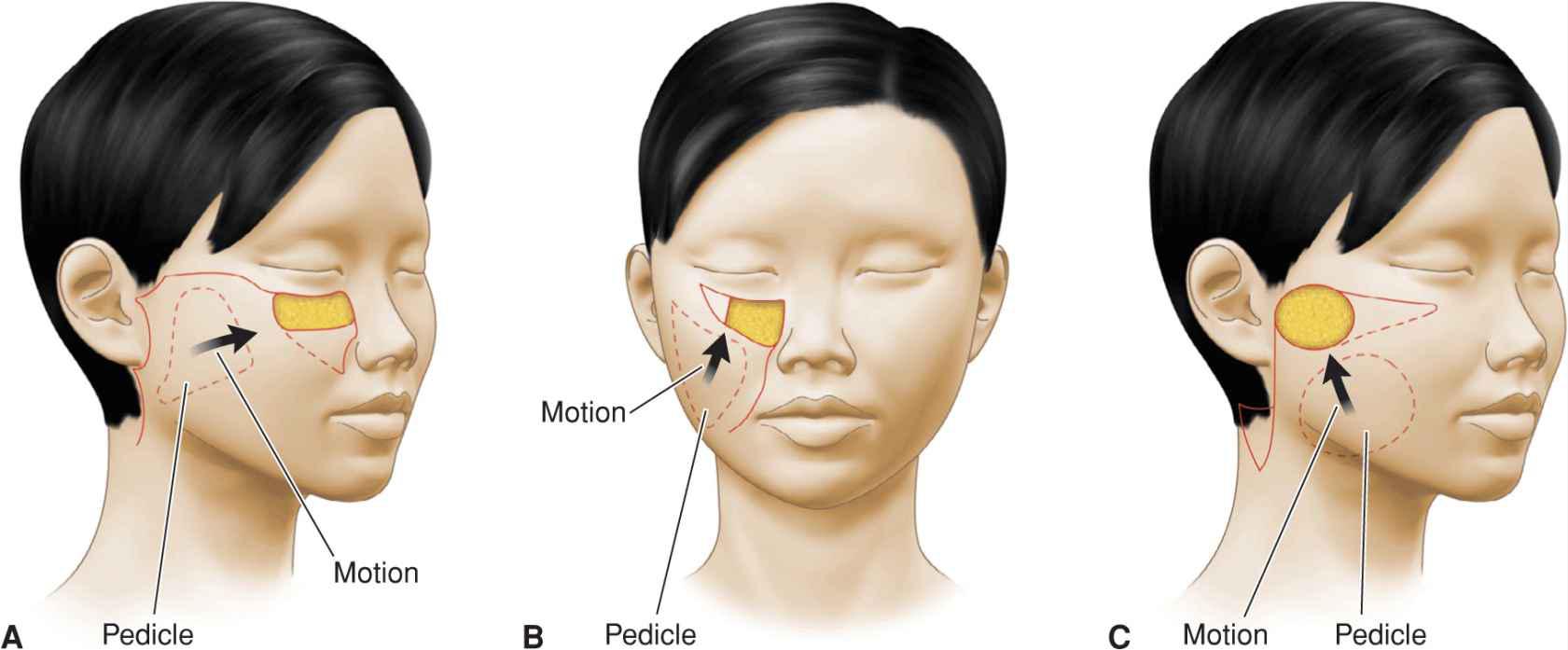

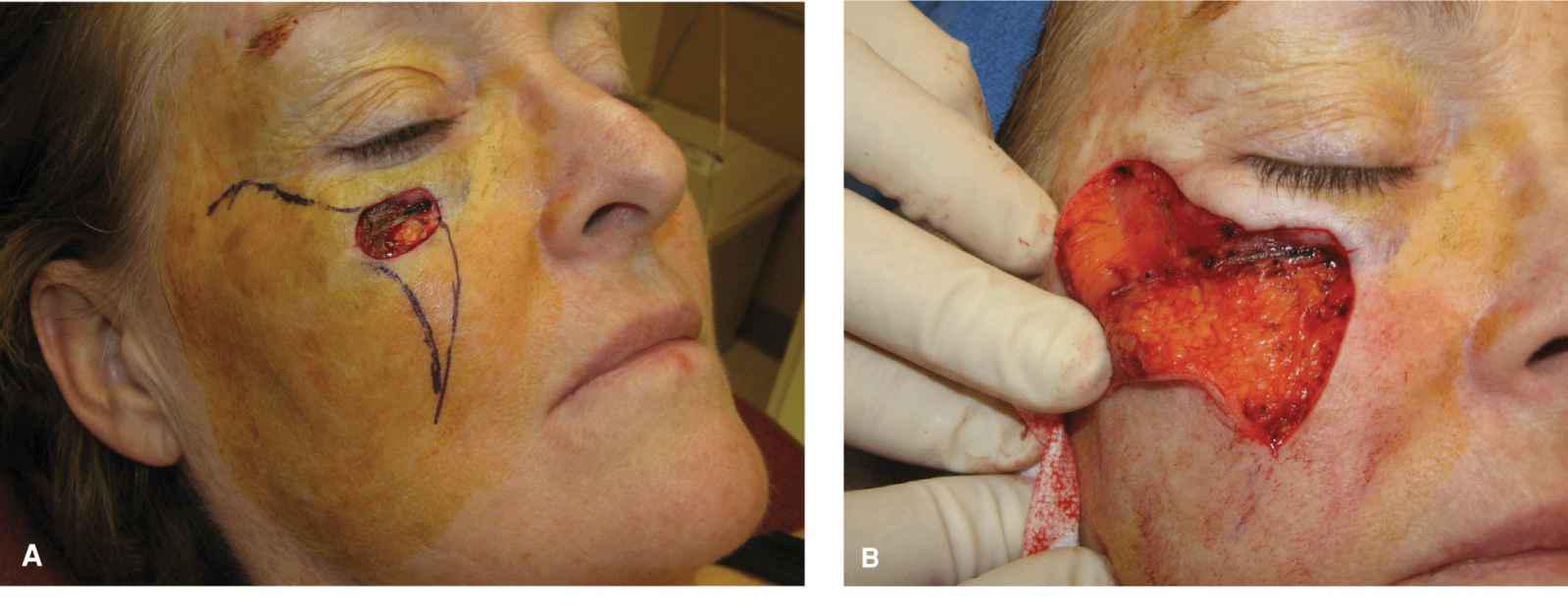

Sliding flaps on the cheek incorporate components of rotation and advancement and are of great benefit in the closure of large and complex wounds. These flaps take advantage of the mobility of the mid and lateral cheek, where deep and abundant, highly vascularized adipose creates a mobile and reliable pedicle (Fig. 11.5).3

Figure 11.5 Large sweeping flaps on the cheek. (A) Large operative wound of the medial cheek repaired with a rotation flap. The flap is pivoted on an inferior pedicle and rotated medially. (B) Medial cheek wound repaired with a rotation flap from below. The flap pivots on a lateral pedicle and is rotated superiorly. (C) Lateral wound repaired with a rotation flap from below. The flap pivots on an inferomedial pedicle

Horizontal Advancement/Rotation Flaps

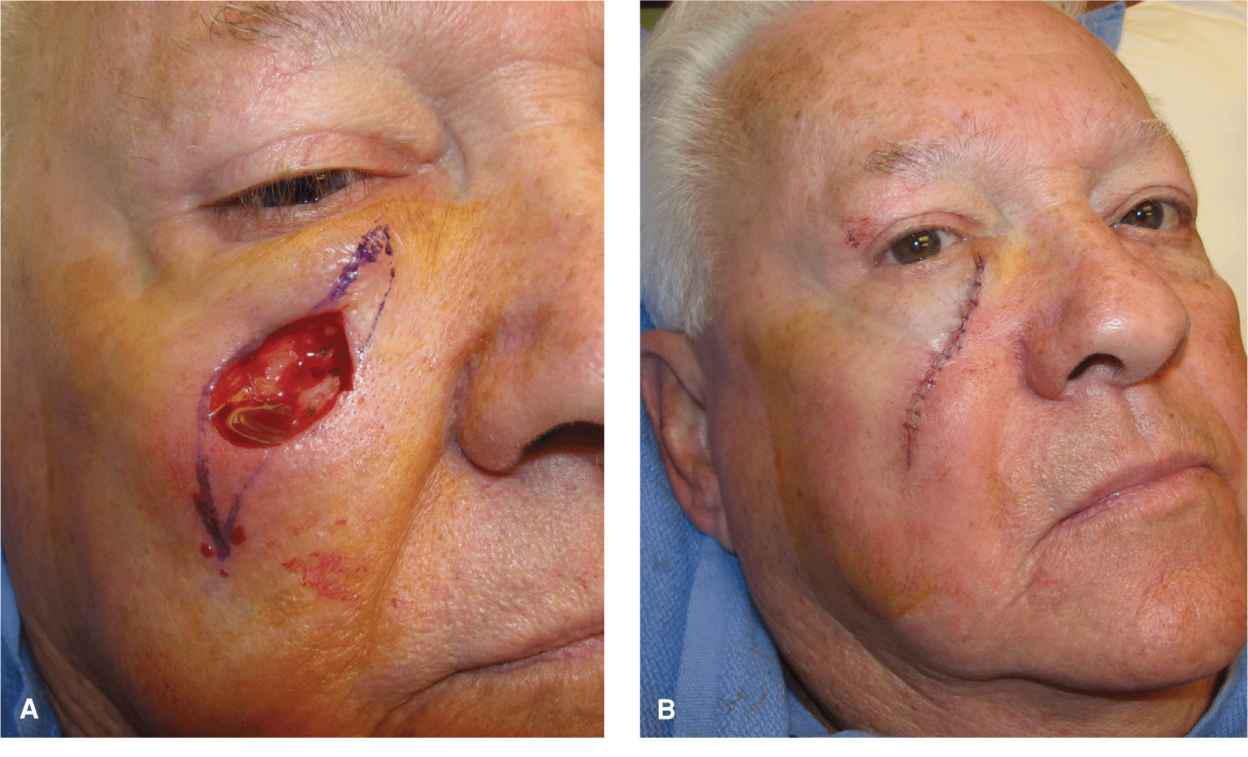

Large cheek wounds are reparable with a broad sweeping flap that extends along the infraorbital crease, arcs superiorly onto the temple, and then down in front of the hairline as needed. The inferomedial standing tissue cone created as the repair is advanced and rotated on its pedicle is taken out along or parallel to the nasolabial fold (Fig. 11.6). Such flaps are modifications of the original Mustarde flap, which was used to repair both eyelid and cheek wounds, and they can be used to repair large surgical defects. They are best elevated just above fascia in the deep, loose adipose. The medial and superior aspects of the flap may require some thinning as they are advanced and rotated into place medially, as the tissue they replace may be of a thinner quality.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree