CHAPTER 9 Abnormal Movements of the Face

Anatomy and function

Facial nerve anatomy

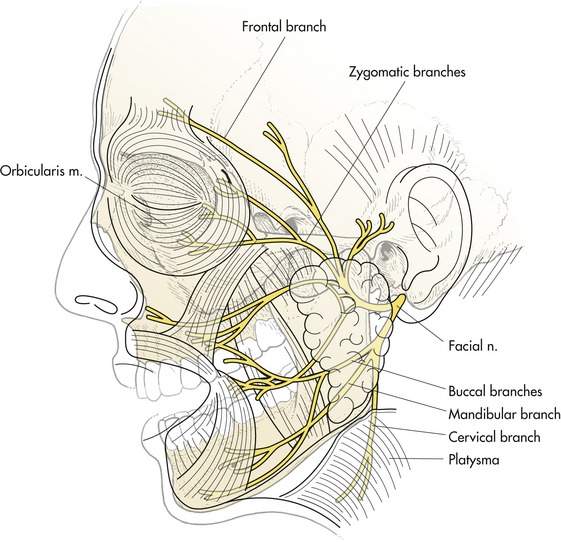

The facial nerve extends from its origin in the brainstem to the innervation of the facial muscles. There are two areas of particular interest to us. The first is the point at which the facial nerve leaves the brainstem in close proximity to the fifth and eighth nerves. The second location is distal to the appearance of the facial nerve trunk in the face anterior to the tragus of the ear. From this point, the facial nerve trunk divides into five branches (Figure 9-1):

These branches innervate groups of the facial muscles selectively. Depending on the cause, facial nerve weakness may involve the entire nerve or individual branches. Bell’s palsy or injury to the nerve proximal to the branching of the facial nerve involves the entire face. Accidental or surgical trauma to the face can result in injury localized to one or more branches. All nerves have the ability to regenerate. Unfortunately, regeneration of the facial nerve after injury frequently occurs in a nonanatomic manner known as aberrant regeneration of the facial nerve. You may see this in a patient after a cheek laceration heals. If you look carefully, you may see that the entire cheek moves as a whole. Similarly, after facial nerve palsy, all branches of the facial nerve will receive the same innervation. Pursing of the lips may also narrow the patient’s palpebral fissure (Figure 9-2).

The facial muscles

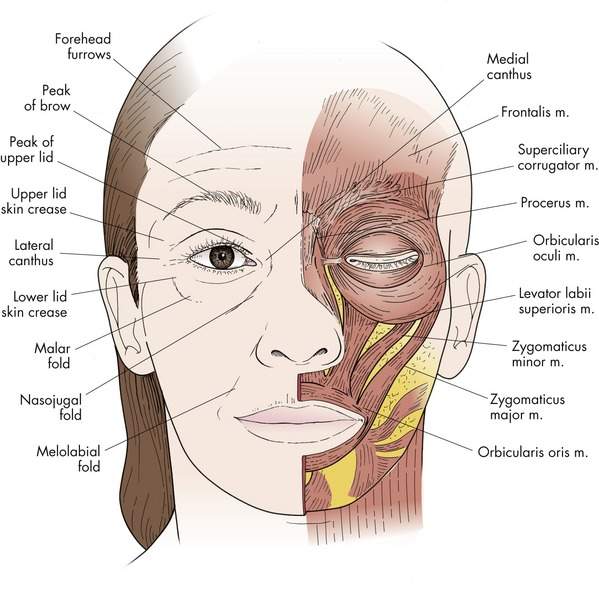

All the muscles of the face are innervated by branches of the seventh nerve. The orbicularis muscle is responsible for eyelid closure. The orbicularis is divided into three areas. The orbital orbicularis causes forceful squeezing of the eye. The preseptal and pretarsal portions of the orbicularis are responsible for the quick blinks that lubricate the cornea. The orbicularis muscle receives innervation from several branches of the facial nerve such that localized trauma has to be fairly extensive to cause a significant paralysis of the orbicularis muscle. You will remember that both the corrugator and the procerus muscles are also innervated by the facial nerve (Figure 9-3). These muscles are known for the creation of the vertical and horizontal glabellar wrinkles respectively. The corrugator muscle also plays a prominent role in the forceful eyelid closure of essential blepharospasm.

Overactivity of the facial muscles

Disorders

Facial tics

Facial tics are voluntary movements of a group of facial muscles. In most situations, the patient is actually not aware that he or she is controlling the movements, however. The condition may be a unilateral spasm of the eye and side of the face or may be simply a bilateral increase in blinking rate. There is often some secondary gain obtained with the tic, although that is difficult to identify. Tics occur most commonly in children, but can also be seen in adults. Probably you have already seen patients with tics. We will discuss their diagnosis in more detail later.

Hemifacial spasm

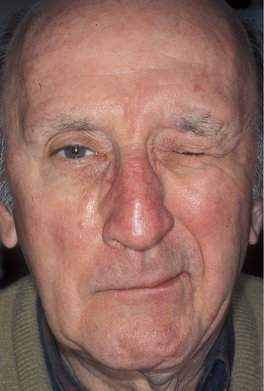

Hemifacial spasm is an involuntary movement of one side of the face (Figure 9-4). The movement may be a quick apparent twitch or may be seen as a sustained spasm involving all the facial muscles on the side. The etiology of facial spasm is thought to be vascular compression of the facial nerve where the nerve leaves the brainstem. Frequently, the hemifacial spasm is accompanied by signs of mild facial weakness and aberrant regeneration.

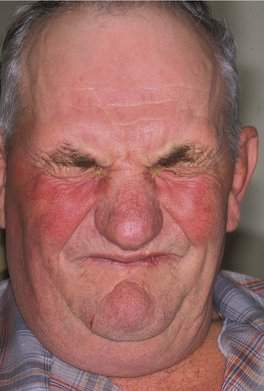

Essential blepharospasm

Essential blepharospasm is an uncontrolled blinking or spasm of both eyes (Figure 9-5). Essential blepharospasm results from progressive degeneration of the central nervous system thought to occur in the basal ganglia. It is most commonly seen in elderly patients. Initially, the disorder may start as increased blinking, but it generally progresses to a more sustained spasm of both eyes with prominent orbital orbicularis and corrugator muscle activity. Abnormal movements of the lower face may be seen in association with essential blepharospasm, known as Meige syndrome (Figure 9-6).

History and physical examination of the overactive face

Several factors are important in arriving at the correct diagnosis:

Orbicularis myokymia and tics tend to occur in younger patients. Orbicularis myokymia and hemifacial spasm tend to occur in older adults. Orbicularis myokymia has an abrupt onset and usually lasts less than a week. The onset of facial tics may follow a particular event, and they frequently disappear spontaneously over a variable period of time. Hemifacial spasm and essential blepharospasm generally do not have a specific onset and tend to progress. As you watch the patient, you will be able to get a feel for the character of the movement problem. Is the muscle activity a quick twitch or a sustained spasm? Are you seeing an involuntary muscle activity (myokymia, hemifacial spasm, or blepharospasm), or is the abnormal facial movement the result of a voluntary coordinated movement of a group of muscles (a facial tic)? Most of all, you will want to determine which parts of the face are involved. This leads the way to determining the diagnosis (Box 9-1).

Box 9-1 Diagnosis of the Overactive Face

Divide the face into four quadrants

First ask yourself if one or both eyes are involved

• If one eye is involved, ask yourself if the whole side of the face is involved

• If you have identified spasm in both eyes, the patient has either a form of blepharospasm or a facial tic

• If the upper and lower face are involved, the patient has Meige syndrome

• Facial tics can be unilateral or bilateral

It is helpful to divide the face into four quadrants when evaluating patients with movement abnormalities (Figure 9-7).

First ask yourself, “Is one or are both eyes involved?”

A tic can involve one side of the face as well. Patients with a unilateral periocular tic show orbital orbicularis activity because it is difficult to lightly blink one eye voluntarily. In most patients, it is easy to identify a tic because the movements seem somewhat bizarre and for some reason you get the idea that the patient is actually doing it. Sometimes I will pass by the examination room a few times to see if the movements are occurring in my absence. Frequently, when I enter the room, the facial movements of the tic will start.

Treatment of the overactive face

Botulinum toxin

The treatment of facial spasm was revolutionized by the introduction of botulinum toxin (Botox®, Allergan Pharmaceuticals, http://www.botoxmedical.com). The toxin serotype A is produced by Clostridium botulinum and is a potent muscle-paralyzing agent. Subcutaneous injection of botulinum toxin into the eyelids and eyebrow provides symptomatic relief of spasm for 3–6 months, depending on the disease process. Botulinum toxin is the primary treatment of hemifacial spasm and essential blepharospasm.

Hemifacial spasm

Botulinum toxin is the treatment of choice for most patients with hemifacial spasm. Five units of botulinum toxin are administered subcutaneously in five sites around the periocular region (Figure 9-8). The choice of sites can be individualized after the initial injection. Most patients with hemifacial spasm have an element of facial weakness, making the effects of the injections last longer than for patients with essential blepharospasm; 4–6 months is common. Remind your patients to use artificial tears frequently throughout the day and lubricating ointment at night for the first few weeks after injection to prevent corneal exposure.

Essential blepharospasm

Essential blepharospasm is a difficult disorder to treat completely. Most of your patients will see improvement with either botulinum toxin injections or surgical myectomy, but very few will be completely asymptomatic after treatment. The disease tends to be progressive and becomes a lifelong condition that will affect your patient for the rest of his or her life. I urge all patients to subscribe to the Benign Essential Blepharospasm Research Foundation newsletter (637 North 7th Street, Suite 102, PO Box 12468, Beaumont, TX 77726-2468, USA, bebrf@blepharospasm.org).

No oral medication has been proven to be effective for treatment of essential blepharospasm. Most patients will see considerable improvement from botulinum toxin injections. Initially 5 units of botulinum toxin are administered subcutaneously in five sites in the periocular area (Figure 9-9). Injections are given subcutaneously above and below the medial and lateral canthal tendons. No injection is made within the orbital bony rims. An additional 5 units is given above the head of the brow in the area of the corrugator and procerus muscles. Patients note the effect of the toxin over the following 48 hours. After the first injection, I check the patient in 1 week. After subsequent injections, I don’t see the patient before the next injection unless there is a problem. The effects of botulinum toxin last approximately 3–4 months. In some cases, you can modify the position of the injection to improve the effect or decrease a particular area of weakness (usually the mouth). I generally do not increase the dose. I will cut the dose in half for a patient who seems particularly sensitive.

Checkpoint

• Understand the mechanism and presentation of orbicularis myokymia, facial tics, hemifacial spasm, and essential blepharospasm.

• Imagine a patient in your office with some facial spasm. While you listen to and watch the patient, use this information to make the diagnosis. Remind yourself of the “facial quadrant” scheme.

• Botulinum toxin (Botox®) injections are the mainstay of treatment for hemifacial spasm and essential blepharospasm. You should know how to treat these disorders. What are the main side effects of botulinum toxin?