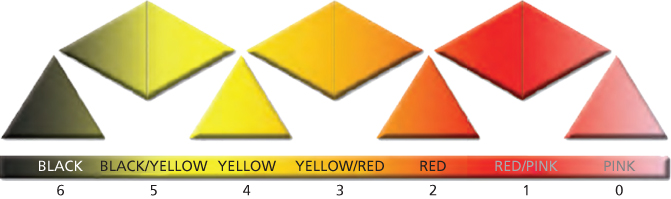

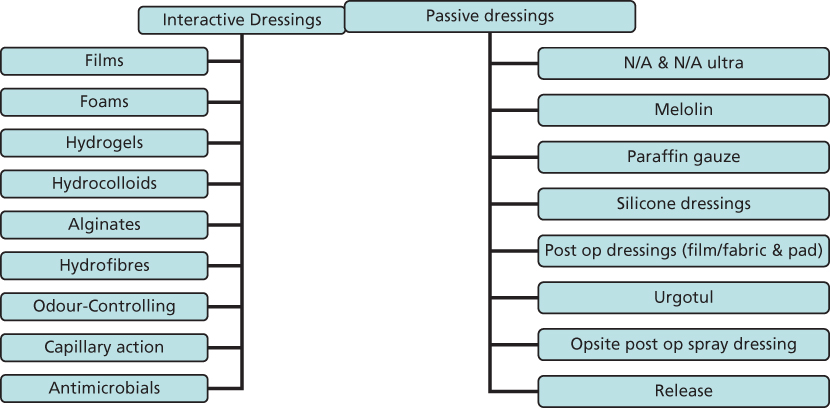

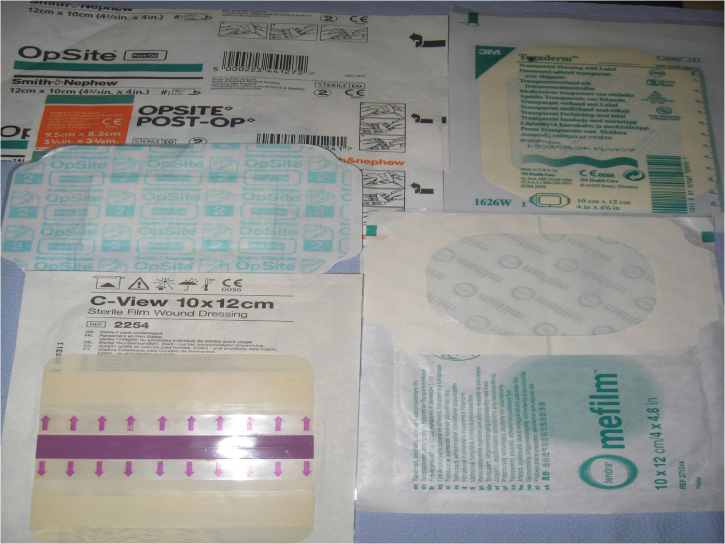

Chapter 25 Effective wound management relies heavily upon the selection of an appropriate dressing and an in-depth understanding of the normal physiology of wound healing. Wound dressings have developed in scientific standing over the years and the complexity of their action is reflected in the vast amount spent on their development to provide the optimum evidence-based wound care; however, there are very few large randomised studies to support their use. Without effective wound assessment there is a risk of selecting an inappropriate product which can lead to delayed wound healing. This chapter provides a practical approach to wound management rather than a detailed look at the physiology of the wound healing process. A wound is a cut or break in continuity of any tissue caused by injury or operation—a break in the skin that may consist of a tear, incision, cut, erosion, puncture or ulcer where the top layer of the skin is breached; if this occurs, tissues are vulnerable to fluid, blood and heat loss, allowing potential invasion of micro-organisms or foreign materials into the skin and possible loss of function. Since the introduction of modern wound dressings such as Granuflex in 1982 and subsequently Kaltostat in 1986 (Convatec), the science of wound healing has progressed rapidly and considerable advances have been made in the development of new products to enhance wound healing; this has led to explosion of wound care products available both in hospital and on FP10 prescription. While a greater choice of dressing products is beneficial to both the patient and the practitioner, it can lead to confusion on which dressings to select for each individual wound as different wound dressings often have specific indications for use. When assessing any wound, there are multiple factors that need to be taken into consideration in addition to the possible underlying aetiology; decisions on which product to apply are based on a full holistic assessment including short- and long-term aims of treatment, patients’ diagnosis and prognosis, availability of the product and the cost. Principles of local wound management include achieving haemostasis, correcting underlying causes, reducing bioburdon (micro-organisms), removing devitalised tissue if present by debridement (Figure 25.1), maintaining moisture balance and protecting the surrounding skin. Figure 25.1 Deep necrotic wound secondary to calciphylaxis being debrided. Source: Grey et al., 2010. Reprinted with kind permission of Wounds UK. Wound bed preparation: Achieving a healthy wound bed is a pre-requisite to the use of many advanced wound care products. The aim of wound bed preparation is to optimise the wound healing environment by removing barriers, that is, necrotic tissue, slough, exudate and bioburdon. Wound bed preparation is the management of the wound to accelerate endogenous healing or to facilitate the effectiveness of other therapeutic measures. The acronym TIME indicates the principles of wound bed preparation. (From Schultz et al., 2003) In order to manage wounds optimally, they are classified into four different types according to the appearance of the wound bed and surrounding tissues, as illustrated by the wound healing continuum below. The wound healing continuum is represented by the tissues in the wound and is colour-based (from Grey et al., 2013) (Figure 25.2). Figure 25.2 Wound healing continuum. Grey et al. (2010). Reprinted with kind permission of Wounds UK. Wound-related factors to be considered in selecting an ideal dressing Key factors affecting wound healing Table 25.1 Wound types and suitable dressings. TVN, tissue viability nurse. Check for sensitivities prior to application. Regardless of type, any wound may be additionally infected or colonised by micro-organisms. If organisms proliferate within the wound an infection may develop, causing a host reaction; this is characterised by pain, oedema, erythema, odour, increased or purulent exudate, abscess formation and local heat. The process of dressing selection is determined and influenced by a variety of factors. These include patient-focused issues and the types of dressings available. Principles for selecting an ideal dressing Modern dressings are described as either passive or interactive, depending on their composition and structure. Passive dressings Interactive dressings Both passive and interactive dressings are subdivided into several categories, as seen in Figure 25.3. Figure 25.3 Wound dressing categories. These are used for superficial, lightly exuding wounds (Figure 25.4). Their major function is to maintain a moist wound bed and allow the exudate to pass through to a secondary dressing and reduce trauma at dressing change. Newer silicone-based dressings are the most effective but tend to be more expensive. Figure 25.4 Non-adherent dressings. Examples include the following: These consist of a thin film of polyurethane, permeable to water vapour and oxygen yet impermeable to water and micro-organisms, allowing gaseous exchange and reducing risk of bacterial contamination (Figure 25.5). Films are flexible and therefore suitable for difficult anatomical sites such as across joints. They can be used on superficial wounds, donor sites, post-operative wounds and as a secondary dressing for other products. These dressings are not recommended for deep, infected or exuding wounds. Removal of these dressings can be traumatic to the surrounding skin and it is therefore recommended to follow the manufacturers’ instructions and remove by the ‘horizontal stretch’ technique. Figure 25.5 Film dressings allow wound monitoring. Examples include Opsite®, Tegaderm®, Bioclusive® and C-View®. These consist of insoluble polymers which are hydrophilic and can absorb excess fluid or produce a moist environment at the wound surface (Figure 25.6). They can be used on dry, sloughy and necrotic wounds which allow rehydration of devitalised tissue and facilitate autolysis. Hydrogel dressings may be suitable for pressure ulcers, leg ulcers and surgical wounds; however, they should not be used for wounds producing high levels of exudate, where gangrene is present, or on diabetic foot ulcers. Hydrogel dressings also come in a sheet format and usually require a secondary dressing to keep them in place. These dressings need to be changed every 1–3 days. Examples include Actiform cool (sheet), Intrasite gel®, Intrasite conformable, Granugel®, Purilon and Nugel®.

Wound Management and Bandaging

OVERVIEW

Introduction

Wounds

Wound types

Wound type

Wound picture

Characteristics

Examples of suitable dressings

Necrotic wounds

Black, dry, eschar devitalised tissue, but can present as wet necrosis/gangrene.

Aims of dressing:

Rehydrate eschar to encourage autolytic debridement if appropriate (not diabetic foot wounds).

Manage exudate/actively debride if wet necrosis/infected.

Hydrogels (non-diabetic)

Hydrocolloids (non-diabetic)

Sharp debridement by competent practitioner only (TVN or Podiatrist)

Surgical debridement

Sloughy

Can range from dry to highly exuding.

Characterised by fibrous sloughy tissue, yellowish in colour.

Aims of dressing:

Remove slough, encourage and facilitate a clean wound bed for the formation of granulation tissue.

Hydrogels

Alginates

Hydrofibre

Hydrocolloids

Larvae

Packing or ribbon forms of dressing required for cavity wounds

Granulating

Clean, low to medium exudate, bright red wound bed with granular, moist, nodular and uneven appearance.

Aim of dressing:

To protect and encourage granulation tissue formation.

Promote a moist wound healing environment.

Alginates

Hydrofibre

Hydrocolloids

Foams

Alginogels

Hydrogels

Epithelialising

Clean, superficial, low to medium exudate, pink in colour, can have white/translucent margins.

Aim of dressing:

Protection to allow further epithelialisation/maturation to occur.

Low and non-adherent dressings knitted viscose

Paraffin gauze

Silicone based products

Film dressings

Infected wounds

Painful to touch, malodorous, greenish/yellow in appearance, friable granulation tissue (delicate, easily damaged) often have increased levels of exudates.

Suitable dressings are

Silver-impregnated dressings:

Silver alginates, hydrofibre, foams

Iodine based dressings

Honey

PHMBs

Larvae

Exuding wounds

Exuding wounds can appear anywhere on the wound healing continuum, however increased exudate is often associated with wound infection.

They often have per-wound skin that is shiny and white (wet and macerated).

Aims of dressing:

Effective exudate management.

Skin care to encourage healing.

Suitable dressings include

Alginates

Hydrofibre

Foams

Super absorbants

Also require barrier protection of per-wound skin:

50:50

Epaderm

Double base

Dressings

Dressings

Types of wound dressings

Non- or low adherent dressings

Film dressings

Hydrogel dressings

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree