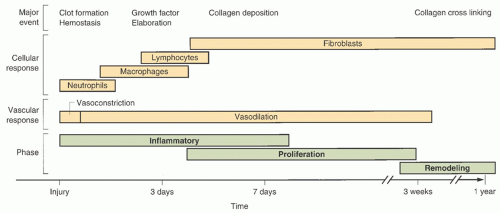

Stage I pressure ulcers

When stage I PrUs are identified, it is important to consider the etiology—namely unrelieved pressure. Since individuals with one PrU are at increased risk to develop more, it’s important to consider pressure reduction both locally and globally. Optimal care of patients with a stage I PrU would include referral to a wound specialist/center. Yet primary care clinicians should develop management goals to reduce progression of the PrU, the development of new ulcers, and complications during the healing process.

The first and most important step in medical management is reducing/relieving the pressure (called “offloading”) to promote wound healing and prevention of new PrUs.

Global pressure relief measures for PrUs can be ordered by the primary care clinician (e.g., a pressure-reducing mattress and/or chair cushion if they sit upright). Federal guidelines identify “group” surface for patients with staged PrUs (

Box 22-3). Durable medical equipment (DME) companies are well versed and can help procure the necessary equipment to offload the patient. Patients may be eligible for a pressure-reducing mattress/hospital bed at home.

Whether lying in bed or sitting in the chair, frequent repositioning, definitely no less than at least every 2 hours, is essential. If the ulcer is on the dorsal surface of the body, consider side-to-side positioning rather than back-lying. If the ulcer has pressure on it when sitting, even with a pressure-reducing chair cushion, the patient’s sit time should be monitored. Consider a sitting restriction of no more than 2 hours up, and 2 hours in bed, as a rotation during awake hours.

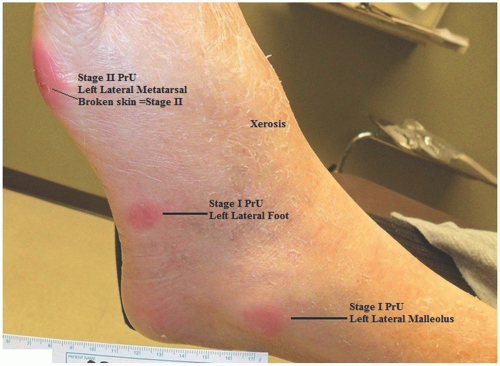

Localized pressure relief measures for stage I PrUs are pressure reduction of the affected area (

Figure 22-2). Consider practical measures such as elevation of heels. Try to avoid foam rings or doughnuts as pressure-reducing devices, because they concentrate the pressure to surrounding tissues rather than redistributing/reducing the pressure interface for the area. Positioning aids such as pillows or wedges or commercial heel offloading boots/devices might be useful.

Topical therapies are not necessary for stage I PrUs. In fact, it was once thought that massage of the affected area would help to reestablish blood supply to the area. However, the current thinking is that massage to the area directly can actually cause more damage to occur and is no longer recommended. If the skin is scaly, a common problem with heel PrUs, for example, gentle application of a moisturizer may be warranted. In general, petrolatum is an effective moisturizer, but multiple compounds are on the market, including mixes of petrolatum and dimethicone, petrolatum and lanolin, and various natural moisturizers, which work as well.

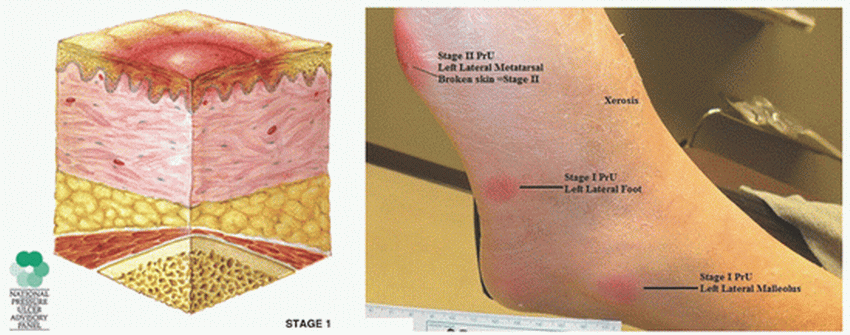

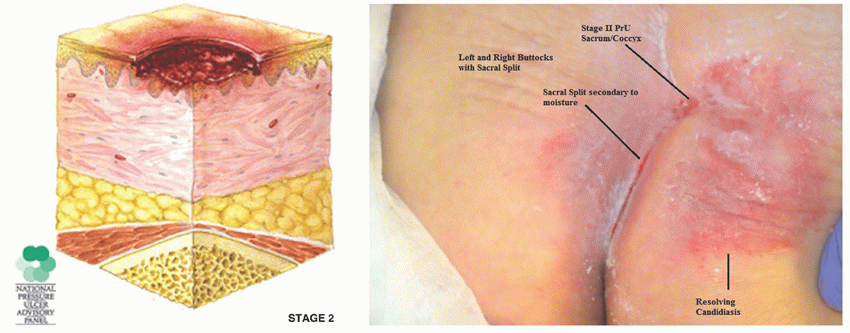

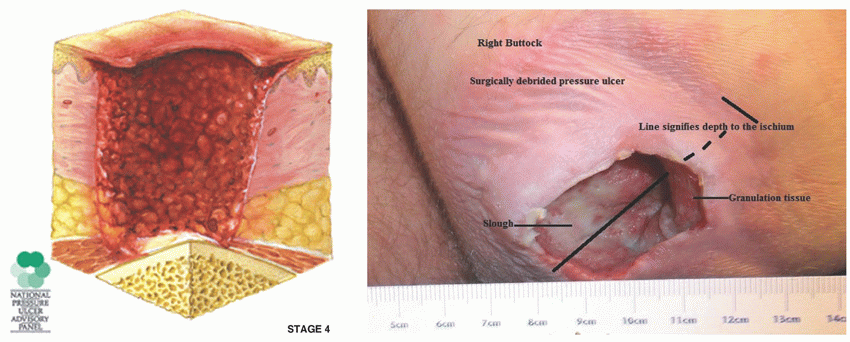

Advanced pressure ulcers (stages II-IV)

The initial management of stages II, III, and IV PrUs is the same as that for stage I, in relation to offloading the pressure with surfaces and repositioning. Management decisions should be based on ulcer presentation. For example, a wound with cellulitis, bad odor, or frank pus may require a local or systemic anti-infective treatment. Advanced-stage PrUs require consultation and continuous care from a wound specialist, unless there is limited access.

Selection of dressings is based on the goal of care, and not on wound etiology. Palliative care goals involve comfort, while active care goals strive for wound healing. Stages III and stage IV PrUs may require packing to fill the void or “dead space” left from tissue destruction. Packing deep wounds is important to prevent infection and abscess formation. Presence of frank pus and odorous exudate demand microbiologic analysis. If palliation is the goal, less frequent

dressing changes are preferred, in general. There are a variety of other complex treatment modalities available that would be best employed by the wound care specialist.

Nutritional screening should be performed on all patients with a stage II, III, or IV PrUs in addition to wound treatment. While visual examination of the patient may indicate general nutritional deficiencies, a thorough dietary assessment, as well as serum testing, is used to analyze the patient’s nutritional status. Patients with PrUs can have significant and undetected nutritional issues that impact their wound healing. It is considered a standard of care to assess the patient’s nutritional status, and it is imperative to incorporate this aspect of care into the wound treatment process. This is addressed at the end of this chapter.

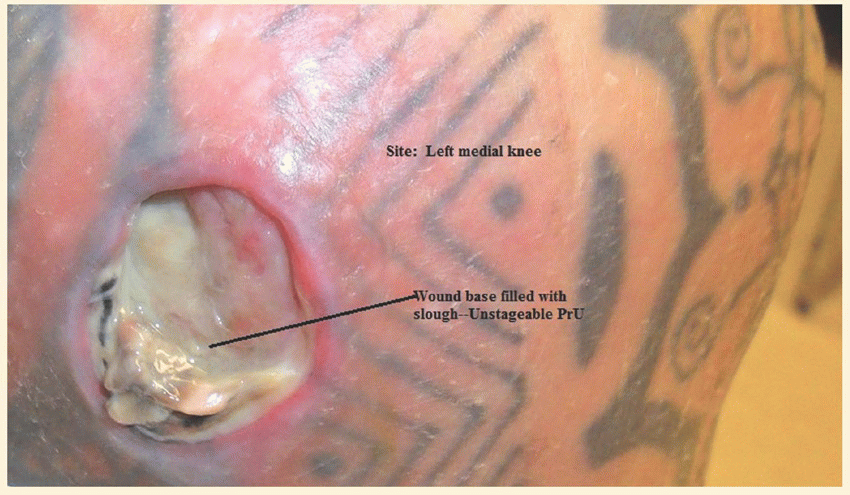

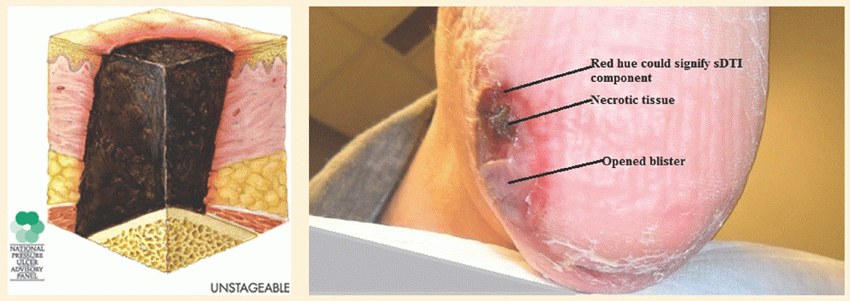

Unstageable pressure ulcers

It is certainly possible to presume the depth of tissue injury, but technically, no classifiable stage can be determined until the wound base is visible. Treatment for unstageable PrUs should follow the same pathway as any advanced PrU, assuming the worst-case scenario of tissue destruction.

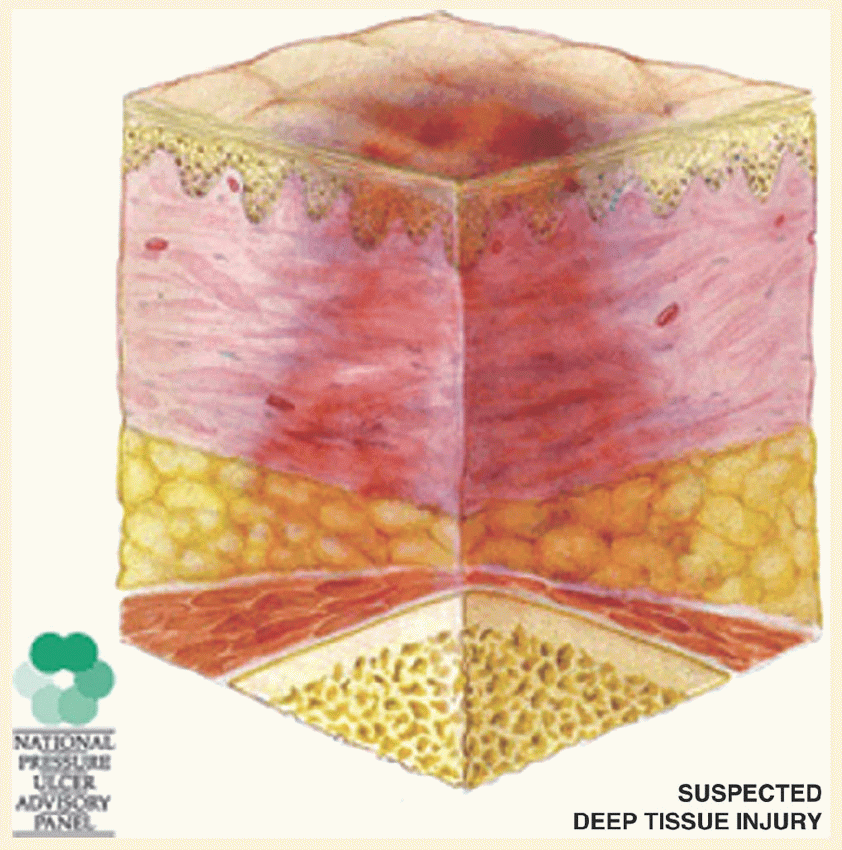

Suspected deep tissue injuries

Outpatient care to halt the progression of a suspected deep tissue injury (sDTI) is limited to simple pressure reduction (discussed above in PrUs) and protection of the area, using a “watch and wait” approach. Hospitalized patients and some wound care centers can offer low-frequency ultrasound therapy (LFUS), which can be beneficial in the treatment of sDTIs. Nutrition and overall health status must be assessed, and steps to intervene with comorbid factors should be implemented.

Topical ointments that contain trypsin and balsam of Peru may increase perfusion to the area applied but carry the risk contact dermatitis. These ointments act as a wound cover and protect the wound. Otherwise, protecting the wound with a soft dressing and changing one to two times per day would be indicated and may provide some relief to the patient. Systemic treatment for a sDTI is not indicated. However, primary care clinicians should address any and all confounding or comorbid conditions that may contribute to the delayed wound healing.