Acne vulgaris (AV) is considered a straightforward diagnosis made clinically without specific diagnostic testing. However, certain disorders may simulate AV, such as multiple small epidermal cysts or deep milia, multiple osteoma cutis, multiple small adnexal neoplasms, and follicular and/or infections characterized by multiple small papules and/or pustules such as gram-positive folliculitis, gram-negative folliculitis, Malassezia folliculitis, keratosis pilaris, and flat warts. This can lead to an erroneous diagnosis and improper management. Acneiform eruptions, often associated with ingestion of certain drugs and chemicals, can confound the clinician regarding AV diagnosis. We present herein an interesting case that was originally misdiagnosed as AV.

Key points

- •

Several dermatologic conditions may simulate facial acne vulgaris, including other papulopustular disorders and inherited syndromes that produce multiple facial papules that mimic comedonal acne lesions.

- •

When monomorphic facial lesions are present that suggest acne vulgaris, consider other conditions; acne vulgaris usually presents with lesions in different stages of evolution.

- •

Many genetic syndromes present with facial papular lesions that may be confused with acne vulgaris. Many of these syndromes are associated with significant systemic abnormalities.

Acne vulgaris (AV) is generally considered to be a straightforward diagnosis that is made clinically without the availability of specific diagnostic testing to confirm the diagnosis. However, there are times when certain disorders may simulate AV, which can lead to an erroneous diagnosis and improper management. Acneiform eruptions, often associated with ingestion of certain drugs and chemicals, can confound the clinician regarding AV diagnosis. Many other skin disorders can mimic AV, such as multiple small epidermal cysts or deep milia, multiple osteoma cutis, multiple small adnexal neoplasms, and follicular and/or infections characterized by multiple small papules and/or pustules such as gram-positive folliculitis, gram-negative folliculitis, Malassezia folliculitis, keratosis pilaris, and flat warts. We present herein an interesting case that was originally misdiagnosed as AV.

History

A 38-year-old white woman presented with a complaint of “acne that does not go away” located on her face.” She stated that she has had acne for “at least 20 years” and “nothing gets rid of the white heads.” She stated that over the past decade, she had developed “red acne bumps and pus bumps” that do go away when she uses topical medications and an oral antibiotic, but come back when she stops the medication; however, the “small white bumps never change.” Previous therapies have included topical benzoyl peroxide 5%–clindamycin 1% gel, tretinoin 0.05% cream, topical adapalene 0.1%, oral doxycycline, and oral minocycline.

The patient was otherwise healthy except for mild seasonal rhinitis controlled effectively with oral loratadine. Her menses are regular and she has never attempted to get pregnant and has no children. Past medical history was remarkable for a “collapsed lung” at age 36 years. She has 2 older brothers, one who had a “collapsed lung” at age 41 years and age 46 years. Her father had a history of a “cyst on his kidney” that was surgically removed at age 44 (type unknown). Her paternal uncle had a “kidney cancer” removed when he was 48 years of age.

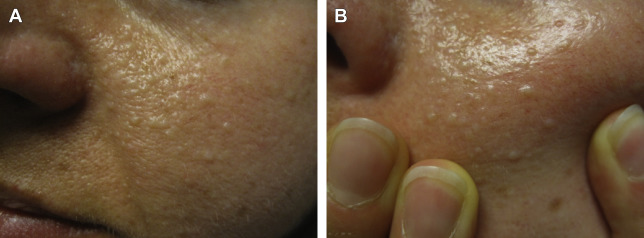

Clinical examination revealed multiple, monomorphic, 2- to 3-mm, round, off-white indurated papules noted diffusely on the face, predominantly involving the cheeks ( Fig. 1 A ). Stretching of the skin enhanced the well-defined appearance of the individual lesions ( Fig. 1 B). No inflammatory papules, pustules, nodules, open comedones, or acne scars were noted. No truncal involvement was noted. Differential diagnosis included comedonal AV (macrocomedones), multiple epidermal cysts, osteoma cutis, and adnexal neoplasms warranting histologic evaluation to differentiate. The monomorphic and indurated nature of the lesions raised concern regarding multiple adnexal neoplasms, which may be associated with an underlying genetic syndrome. Skin biopsy of 2 representative papules both demonstrated fibrofolliculoma. No nonfacial lesions were noted. This finding, along with the personal history of pneumothorax, and the familial history of pneumothorax and renal neoplasms including malignancy led to the diagnosis of Birt–Hogg–Dube (BHD) syndrome. Inquiry into family history revealed that her uncle with kidney malignancy underwent genetic testing which revealed an FLCN (folliculin) mutation, which confirmed the diagnosis of BHD syndrome. Although the patient was not overweight, she did report having axillary and periocular “skin tags” removed in the past, which are also a manifestation of BHD syndrome.

The patient was informed of the diagnosis and importance of further evaluation and periodic follow-up was stressed verbally and in writing, including radiographic evaluations of the chest and abdomen region to assess possible pulmonary and renal abnormalities. She delayed having the workup completely despite having good medical insurance coverage for services and stressed that her major concern was her facial appearance. Unfortunately, she did not follow-up with consultations arranged to complete her workup despite being contacted by phone and letter, and moved away from the area.

History

A 38-year-old white woman presented with a complaint of “acne that does not go away” located on her face.” She stated that she has had acne for “at least 20 years” and “nothing gets rid of the white heads.” She stated that over the past decade, she had developed “red acne bumps and pus bumps” that do go away when she uses topical medications and an oral antibiotic, but come back when she stops the medication; however, the “small white bumps never change.” Previous therapies have included topical benzoyl peroxide 5%–clindamycin 1% gel, tretinoin 0.05% cream, topical adapalene 0.1%, oral doxycycline, and oral minocycline.

The patient was otherwise healthy except for mild seasonal rhinitis controlled effectively with oral loratadine. Her menses are regular and she has never attempted to get pregnant and has no children. Past medical history was remarkable for a “collapsed lung” at age 36 years. She has 2 older brothers, one who had a “collapsed lung” at age 41 years and age 46 years. Her father had a history of a “cyst on his kidney” that was surgically removed at age 44 (type unknown). Her paternal uncle had a “kidney cancer” removed when he was 48 years of age.

Clinical examination revealed multiple, monomorphic, 2- to 3-mm, round, off-white indurated papules noted diffusely on the face, predominantly involving the cheeks ( Fig. 1 A ). Stretching of the skin enhanced the well-defined appearance of the individual lesions ( Fig. 1 B). No inflammatory papules, pustules, nodules, open comedones, or acne scars were noted. No truncal involvement was noted. Differential diagnosis included comedonal AV (macrocomedones), multiple epidermal cysts, osteoma cutis, and adnexal neoplasms warranting histologic evaluation to differentiate. The monomorphic and indurated nature of the lesions raised concern regarding multiple adnexal neoplasms, which may be associated with an underlying genetic syndrome. Skin biopsy of 2 representative papules both demonstrated fibrofolliculoma. No nonfacial lesions were noted. This finding, along with the personal history of pneumothorax, and the familial history of pneumothorax and renal neoplasms including malignancy led to the diagnosis of Birt–Hogg–Dube (BHD) syndrome. Inquiry into family history revealed that her uncle with kidney malignancy underwent genetic testing which revealed an FLCN (folliculin) mutation, which confirmed the diagnosis of BHD syndrome. Although the patient was not overweight, she did report having axillary and periocular “skin tags” removed in the past, which are also a manifestation of BHD syndrome.