Venous Physiology and Pathology

VENOUS PHYSIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

VENOUS PHYSIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

In order to treat venous problems properly, it is essential to understand the normal pattern of venous blood flow and the effects of venous valves. For practical purposes, the venous system of the leg can be considered to have two major parts, a deep component and a superficial component. The superficial veins serve as a primary collecting system and are connected through perforating veins into the deep veins, which normally carry about 90 percent of the blood from the leg back to the central circulation.

Normal Venous Physiology

As arterial blood flows into the leg, distal superficial veins and venous reservoirs are constantly filling and must be emptied into the deep veins regularly and then somehow returned to the right side of the heart. Venous return from the leg must flow uphill against gravity, against fluctuating thoraco-abdominal pressures, and sometimes in the face of additional backpressures such as the elevated right atrial pressures of congestive heart failure. This process depends on the patency of the flow circuit and on the correct functioning of a complex series of valves and pumps.

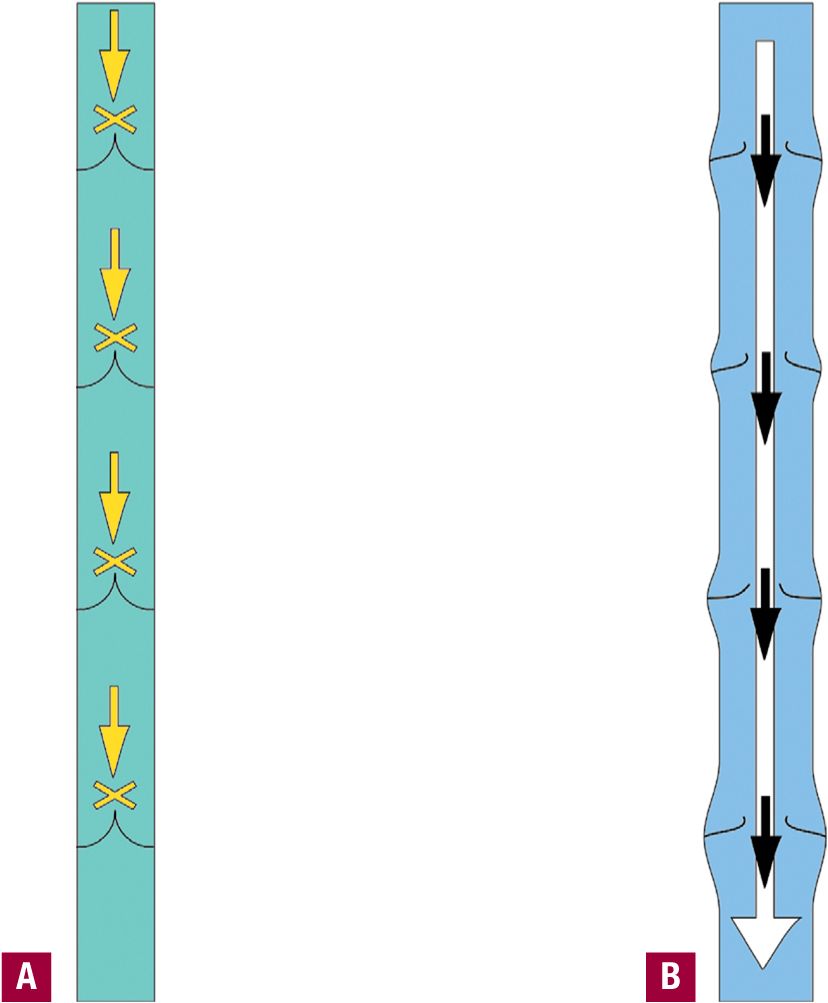

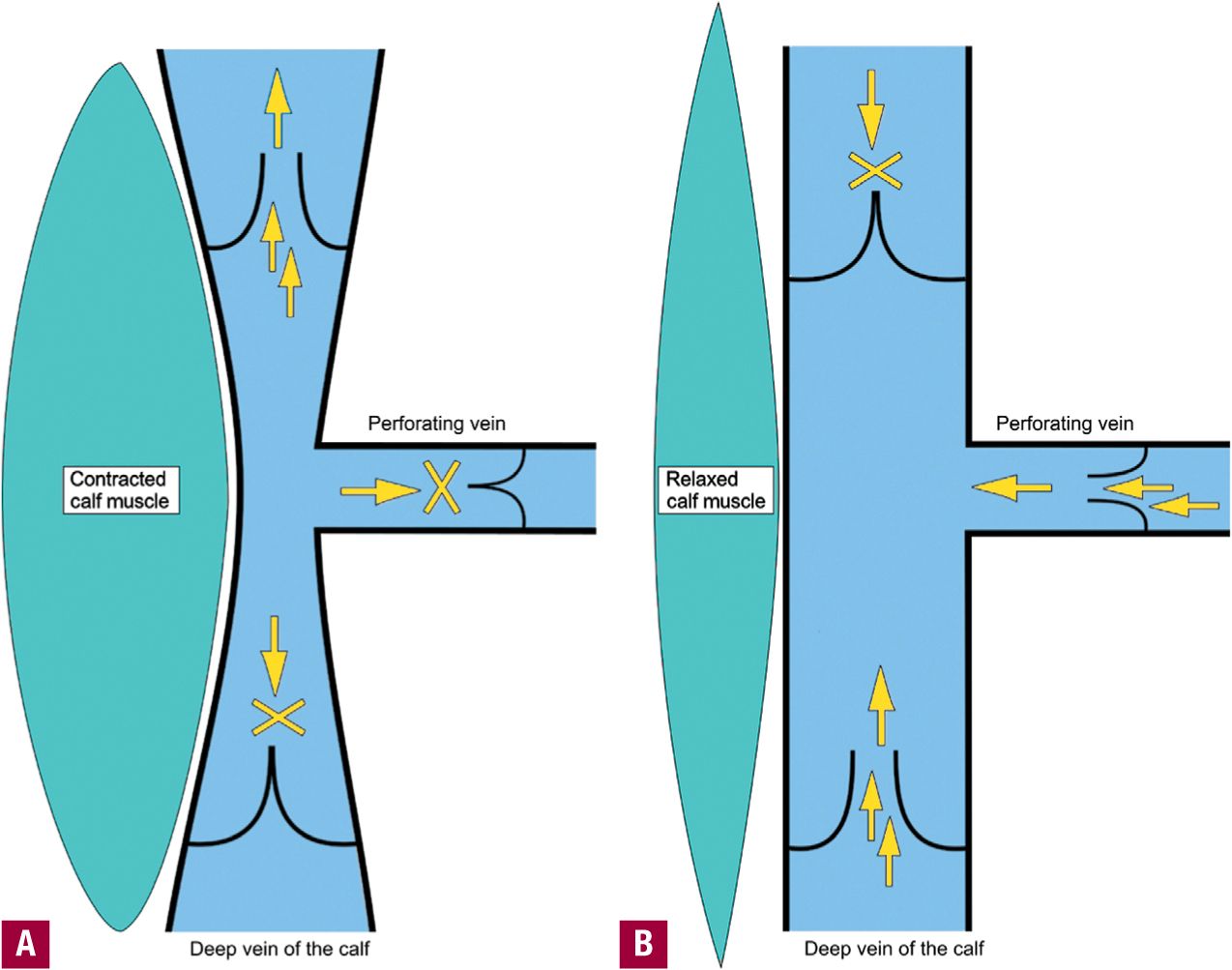

CALF MUSCLE PUMP When muscles of the calf and leg contract, they compress deep veins within the muscles, forcing the blood in those veins to flow upward past venous valves. When the muscles relax, the deep veins expand and draw in more blood from superficial collecting veins (Figure 4-1). This system is known as the “calf muscle pump” and sometimes is referred to as a “peripheral heart.” Veins and muscles of the calf and of the foot both play an important role in the normal functioning of this system, which can achieve pumping pressures of several hundred torr before valve failure occurs.1 Particularly important venous capacitance reservoirs are found within the soleus muscle and within the deep muscles of the foot.

![]() FIGURE 4-1 A. The calf muscle pump with muscle contracted. A pressure of 2 atm forces the vein segment to empty. B. The calf muscle pump with muscle relaxed. Zero or negative pressure permits the vein segment to refill.

FIGURE 4-1 A. The calf muscle pump with muscle contracted. A pressure of 2 atm forces the vein segment to empty. B. The calf muscle pump with muscle relaxed. Zero or negative pressure permits the vein segment to refill.

VENOUS VALVES Normal deep and superficial veins contain oneway valves that permit flow from the superficial system into the deep system and from distal to proximal. The calf muscle pump cannot function without competent valves both above and below. Venous valves are bicuspid and are located every few centimeters in all normal veins below the level of the common femoral vein.2

Recent studies of venous valves indicate that there may be several different types of valves including some that offer some resistance but do not shut completely.3 Normal venous valves can withstand pressures of up to 3 atm, but congenitally weak valves and valves that have softened due to hormonal influences may malfunction to permit retrograde flow at lower pressures.

AMBULATORY VENOUS PRESSURE Immediately after ambulation, the normal pressure within the veins of the lower extremity is extremely low, because a normally functioning muscle pump has emptied both the superficial and deep venous systems. Normal inflow to the lower extremity veins is purely via arterial inflow; thus, the normal venous system will be refilled only after 3–5 min of standing. After prolonged standing, the entire venous system is filled, the valves float open, and venous pressure rises to a maximum that is exactly equal to the height of the standing column of venous blood from head to foot (Figure 4-2). This condition triggers an urge to move the legs, activating the muscle pumps and re-emptying the legs. Any condition that increases venous inflow or impedes venous outflow will cause an elevated venous pressure during or immediately after ambulation.

![]() FIGURE 4-2 A. Immediately upon standing, veins are emptied and valves are closed. Hydrostatic pressure is limited to the height between valves. B. After prolonged standing, veins are full and valves have opened. Hydrostatic pressure rises to the full height of the column of blood.

FIGURE 4-2 A. Immediately upon standing, veins are emptied and valves are closed. Hydrostatic pressure is limited to the height between valves. B. After prolonged standing, veins are full and valves have opened. Hydrostatic pressure rises to the full height of the column of blood.

Venous Pathophysiology

Impaired venous outflow and abnormal (retrograde) venous inflow are the two principal causes of venous circulatory pathology. Venous pathology can be related to the deep system, the superficial system, or it can be of mixed etiology. It can result from primary muscle pump failure, from venous obstruction (thrombotic or nonthrombotic), or from venous valvular incompetence, which may be deep or superficial and segmental or whole-leg. Nearly any abnormality of venous circulation will ultimately result in the development of varicose veins (Table 4-1).

TABLE 4-1

Physiologic Causes of Venous Insufficiency

Failure of calf muscle pump leading to high ambulatory venous pressure

Muscle wasting

Neuromuscular disease

Prolonged standing

Failure of valves

Venous distension

Valve deformation

Deep obstruction

Deep incompetence

Primary agenesis

Prior valve damage

Direct trauma

Dilation with secondary valve failure

Perforator incompetence

Superficial incompetence

Gravitational hydrostatic pressure

VALVE FAILURE Valve failure permitting venous reflux is the most common cause of symptomatic venous pathology. Many different mechanisms can lead to valve malfunction and reflux. Reflux is common after thrombosis or other inflammatory processes have damaged valve leaflets. Chronic turbulent blood flow may also lead to reflux by causing atrophic changes of the valves. Congenital conditions may result in malformed valve leaflets. When a vein becomes distended due to overfilling, the base of the valve (the “valve sinus”) may expand so far that normal valve leaflets can no longer form a tight seal. Even when the valves themselves function normally, leakage around the base (“commisural reflux”) may be induced by any process that deforms a valve at its base. Superficial vein walls are inherently weak because (with the exception of the greater saphenous vein in the thigh) they are supported only by subcutaneous tissue and skin rather than by fascia and muscle. With prolonged standing, hydrostatic pressure can cause even “normal” veins to become distended to the point where they permit reflux.4 External compression may therefore play an important role in the protection of a “normal” leg by supporting the veins from distention.

PRIMARY MUSCLE PUMP FAILURE The calf muscle pump can fail to operate because of muscle wasting, neuromuscular disease, local edema, deep fasciotomies, or local vein valve failure within the muscle fascia sheath. When there is a complete failure of the calf muscle pump, venous blood is never effectively pumped out of the distal extremity at all.1 The immediate post-ambulatory venous pressure will be nearly as high as the pressure after prolonged standing. The volume of venous blood that suffuses the extremity will be increased. A smaller fraction of the extremity’s venous blood will return to the central circulation each minute, and because arterial blood must flow into congested tissues with elevated hydrostatic pressure, the volume of arterial inflow will actually be reduced. This situation often leads to ulceration of the lower extremity.5

DEEP OBSTRUCTION Partial obstruction of the deep veins may have little effect upon venous outflow, but severe obstruction of the deep veins produces secondary muscle pump failure. In this case, the muscle pump produces an appropriately high outflow pressure with each contraction, but the volume of venous blood pumped out of the calf is reduced because of the reduced diameter of the outflow tract.

DEEP INCOMPETENCE If outflow tracts are open and the muscle pump itself is functional but the valves of the deep veins permit reflux (because of primary agenesis, prior valve damage, direct trauma, or dilation with secondary valve failure), then venous blood will be pumped out of the calf in normal volumes, but extremity refill will include both normal arterial inflow and pathologic deep venous retrograde flow. Total failure of all deep vein valves allows venous blood to flow backward rapidly from the vena cava down into the legs upon standing and can produce orthostatic hypotension.

In patients with deep venous valve incompetence, the venous pressure immediately after ambulation may be slightly elevated or it may even be normal, but the veins will refill and dilate very quickly. After only a few seconds of standing, the venous pressure will be nearly as high as the normal pressure after prolonged standing. The volume of venous blood that suffuses the extremity will be increased. A smaller fraction of the extremity’s venous blood will return to the central circulation each minute, and because arterial blood must flow into congested tissues with elevated hydrostatic pressure, the volume of arterial inflow will be reduced as in primary pump failure.

PERFORATOR INCOMPETENCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree