A hypersensitivity reaction is an exaggerated and pathologic response by the immune system to a self- or foreign antigen. Hypersensitivity reactions differ in the mediators involved, mechanisms, timing, and clinical manifestations; however, there may be similar morphologic appearances making clinical diagnosis a challenge. There are four types of hypersensitivity reactions: Type I is immediate, anaphylactic; mediated by IgE, histamine, leukotrienes; and includes urticaria and angioedema. Type II is cytotoxic; mediated by IgM or IgG, complement; and includes some drug reactions and transfusion reaction. Type III is mediated by IgG or IgM antibodies in immune complexes; includes serum sickness, arthus reaction, vasculitis, or systemic lupus erythematosus. Type IV is delayed/cell mediated; activates reactions with antigen-specific T cells, such as poison ivy, allergic contact dermatitis, tuberculin reaction.

The hypersensitivity reactions addressed in this chapter include vasculitis, urticaria and angioedema, erythema multiforme (EM), and erythema nodosum (EN). These reactions range in severity from mild to life-threatening and can be triggered by drugs, infectious agents, foods, environmental allergens, malignancies, autoimmune disorders, other systemic illness, or unknown etiologies.

VASCULITIS

Vasculitis is an inflammatory process which involves the walls of any size or type of vessel causing damage that results in tissue necrosis. Cutaneous vasculitis may be limited to the skin only, may be a primary cutaneous vasculitis with secondary systemic involvement; or a cutaneous manifestation of a systemic vasculitis. All categories of vessels can be affected, including small, medium-sized, and large vessels of the arterial and/or venous systems.

Small vessels include arterioles, capillaries, and postcapillary venules that are found in the superficial and mid-dermis of the skin (

Table 16-1). Medium-sized vessels refer to the main visceral arteries and veins, and the small arteries and veins within the deep dermis or subcutaneous tissue (

Table 16-2).

Large vessels are the aorta, its major branches and corresponding veins, and other named arteries such as pulmonary or temporal artery. Cutaneous involvement occurs almost always with vasculitis of small and medium-size vessels and therefore the large-vessel vasculitides will only be briefly mentioned in this chapter.

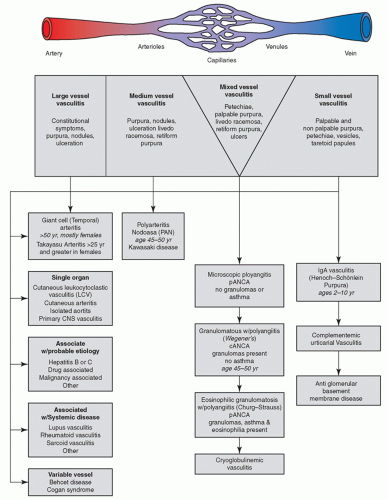

The clinical spectrum of vasculitis presents a diagnostic challenge even for the experienced dermatology or rheumatology provider. In an attempt to classify the vasculitides, several schemes have been proposed; historically the classification was based on vessel size. Other criteria have been developed based on clinical signs and symptoms, histopathology, historical data, and the presence or absence of internal organ involvement. Most recently, The International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference on the Nomenclature of Systemic Vasculitides (CHCC2012) updated their original work of 1994. This is neither a classification system nor a diagnostic system, but rather it defines the nomenclature that should be used for a specifically defined disease process (

Figure 16-1). For example, if a vasculitis is caused by direct invasion of pathogens, then the vasculitis should be specified as such (i.e., rickettsial vasculitis or syphilitic aortitis) rather than “infectious vasculitis.” Although there are differences among these criteria, a shared defining feature of vasculitis is an inflammation of blood vessel walls at some time during the course of the disease.

Furthermore, CCHC has renamed the vasculitis previously known as cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis and is now referred to as cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis (CSVV). By definition, CSVV has the histologic findings associated with leukocytoclastic vasculitis but the involvement is limited to the small blood vessels of the skin, and no other organ system is involved. This may also be referred to as single-organ vasculitis. The following section will focus on the CSVV that is more commonly seen in the primary care setting, the importance of screening for systemic organ involvement, differential diagnoses, diagnostics, and prompt management.

Clinical Presentation

The importance of a detailed physical examination that accurately identifies the morphology of the presenting lesions cannot be overemphasized. Clinical presentation is critical in developing a differential diagnoses for vasculitis. It is absolutely essential that clinicians evaluate the patient for systemic involvement, which may present as fever, cough, myalgia, hemoptysis, abdominal pain, melena, weight loss, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, hypertension, headache, visual disturbances, and renal insufficiency (urine sediment with protein and red and white cells).

The morphology of the cutaneous findings in any vasculitis will depend on the size of the vessels primarily affected and will provide clues to the type of vasculitis. Clinicians should understand the terminology frequently used in discussing these dermatoses (

Table 16-4). Small-vessel vasculitis (SVV) results in petechia, purpura, erythematous macules, papules, and pustules (

Figure 16-3).

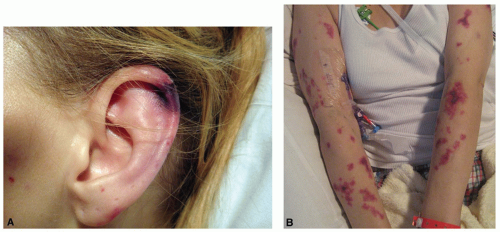

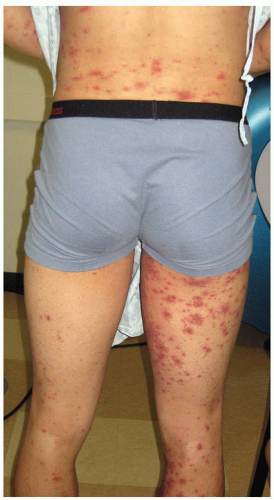

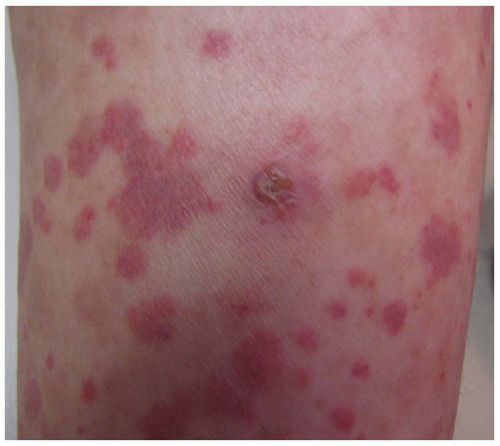

Palpable purpura occurs when vasculitis is present

in postcapillary venules and is the hallmark of cutaneous vasculitis (

Figures 16-4,

16-5 and

16-6). Lesions typically evolve within 7 to 10 days of a causative exposure, and erupt in crops lasting about 1 to 4 weeks. The size of SVV lesions can range from 1 mm to several centimeters and may be asymptomatic, itchy, or painful. Edema may develop if nephritis is present. Painful nodules, pustules, and necrotic ulcers can present in specific types of SVV like granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). The unusual distribution of lesions in GPA found in the oral and nasal mucosa should heighten the clinician’s index of suspicion. Yet most SVV lesions favor dependent sites such as legs and feet, or areas affected by trauma and tight-fitting clothing. The buttocks or back of a bedridden patient may be involved and reflects the influence of venous pressure due to gravity.

Medium-vessel vasculitis occurs predominately in medium-size and small arteries (i.e., visceral arteries and branches). Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a necrotizing medium-vessel vasculitis presenting as nodules (similar to EN), palpable purpura, and vesicles/bullae. Livedo reticularis may progress to ulcerations usually located on the lower extremities. The lesions are painful and may be accompanied by edema. Patients with PAN often have systemic symptoms.

Kawasaki disease (KD) is also a vasculitis of medium-size arteries, including coronary arteries and aorta. Although it is rare and self-limiting, recognition of the clinical presentation is important to avoid cardiac sequelae. It is more common in childhood and is discussed under Childhood Vasculitis.

Large-vessel vasculitis involving the aorta and large arteries means that affected patients have systemic involvement and appear much sicker. Ulcerations and sometimes gangrenous digits are seen with large-vessel involvement. Giant cell arteritis (GCA) occurs in patients over 50 years, who report constitutional symptoms along with temporal artery tenderness, visual loss, polymyalgia rheumatica, headache, jaw claudication, and temporal enlargement with absent pulse is common. Clinicians should assess the patient for aortic involvement, including signs and symptoms of aneurysm. In contrast, Takayasu arteritis is more prevalent in females younger than 50 years and affects the aorta and major branches. Granulomatous inflammation affects any or all of the organs, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality.

Diagnostics

The general approach for any patient with vasculitis should be to rule out other diseases that may mimic vasculitis; look for any underlying or secondary cause (disease, infection, drug, or malignancy); perform diagnostics to confirm the presence of a vasculitis; and conduct additional tests to identify the type and severity of the vasculitis.

A detailed history, review of systems, and clinical presentation will be invaluable in guiding the clinician’s development of a differential diagnosis or suspicion for secondary causes (

Table 16-5). The initial diagnostic test should be a punch or excisional biopsy, the gold standard for evaluation of vasculitis, which should be taken from the center of a new lesion (preferably 24-48 hours old), making sure to collect some of the subcutaneous tissue if evaluating deeper, larger vessels. The histopathologic features of the biopsy can aid in identifying the type of vasculitis as well as other features which may indicate other systemic disease (i.e., interface dermatitis suggestive of connective tissue disease). Additional punch biopsy for direct immunofluorescence (preserved in Michel’s medium) may be helpful in identifying the deposition of immunoglobulins and complements in the blood vessels (i.e., Henoch-Schönlein purpura [HSP]).

A complete blood count with differential should be part of the initial workup. Patients with a primary vasculitis rarely have leukocytosis or thrombocytopenia, which, if present, should prompt further evaluation for an underlying disease, malignancy, or infection. Eosinophilia is seen in Churg-Strauss syndrome. Anemia could signify underlying lupus erythematosus or malignancy. A C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are usually elevated but are nonspecific markers of systemic inflammation. Blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and electrolyte abnormalities may reflect kidney involvement. Abnormal liver function tests may be associated with underlying liver disease or malignancy. A stool guaiac will help assess for vasculitis of the bowel in patients with abdominal pain. Urinalysis with microscopy that is positive for red blood cell casts is suggestive of glomerulonephritis, while proteinuria is common in lupus nephritis. A chest x-ray may be recommended if the patient’s review of symptoms or clinical presentation suggests pulmonary involvement and may reveal pulmonary infiltrates, nodules, patchy consolidation, pleural effusion, and cardiomegaly.

Management

Treatment of vasculitis should be based on type and severity, as well as the presence of organ involvement. Management of primary CSVV seen in primary care will be the focus of this section. Medium- and large-vessel vasculitis are beyond the scope of this text and should be managed by dermatologists or appropriate specialists.

Most primary CSVV is mild and self-limiting. If an offending antigen like a drug is identified, then removing the source is the obvious first step. Underlying infection or disease should be treated at the outset. Treatment of CSVV (without systemic involvement) should proceed with supportive care, including leg elevation, rest, and gentle compression of legs for comfort. However, tight restrictive clothing may aggravate susceptible skin regions and should be avoided. Pain and inflammation can be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and pruritus may be attenuated with antihistamines such as hydroxyzine or diphenhydramine. Class I topical corticosteroid (TCS) ointment may also be helpful for adult patients, most of whom will not require systemic measures.

Short-term oral corticosteroids (prednisone) may be considered in patients with chronic (active disease that persists for more than 4 weeks) or recurring CSVV if hemorrhagic blisters and ulcerations are present. The dose and duration of treatment are dependent on the severity. A dosage of 0.5 mg/kg/day can be prescribed for 1 to 2 weeks or until new lesions cease to erupt. A taper over 2 to 4 weeks may be necessary and usually meets with complete resolution. Chronic forms of CSVV, or those with more severe cutaneous

disease, may require higher doses of prednisone dosed 1 mg/kg/day to control symptoms. Since long-term use of corticosteroids has the risk of significant side effects, transitioning the patient to a steroid-sparing agent (i.e., colchicine, dapsone) is important. Patients on dapsone need G6PD testing prior to initiating therapy and careful monitoring for hemolytic anemia during therapy. Pentoxifylline has been effective when the CSVV is resistant. Recalcitrant CSVV or SVV with systemic involvement often requires management by dermatology specialists with azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin, mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab, or plasmapheresis.

Referral and Consultation

The initial presentation and evaluation of vasculitis may begin in the primary care office, and patients with localized or early vasculitis can be managed symptomatically with removal of an offending antigen. Most patients are referred to a dermatology provider when there is extensive cutaneous involvement, threatened organ involvement, and relapse or disease progression despite treatment. A number of specialists should be consulted based on findings, including a nephrologist, pulmonologist, cardiologist, and otolaryngologist. Surgical consult may be necessary if necrotizing or ulcerative lesions are present.

Prognosis and Complications

If a drug or infection is the cause, there may only be one episode with spontaneous resolution; however, if SVV is associated with a systemic disease, such as hepatitis C infection or rheumatoid arthritis, treatment considerations will be different. Ultimately, the best indicator of prognosis in any vasculitis with systemic involvement depends on the size of the vessel and organ involved. Long-term implications include the possibility of multiple episodes with recurrent crops of vasculitic lesions appearing for months or years.

Patient Education and Follow-up

Patients receiving short-term corticosteroids should be advised of possible adverse effects, including hypertension, glucose intolerance, sleep disturbance, hirsutism, weight gain, and avascular necrosis of the hip. Patients on prednisone for extended periods of time should have baseline bone mineral density testing and receive education about corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis, including weight-bearing exercise, smoking and alcohol cessation, and fall prevention in the elderly. Consider calcium with vitamin D supplementation and bisphosphonates for high-risk individuals. Blood pressure and serum glucose should be monitored. Patients of childbearing age should always be counseled regarding adequate birth control measures, especially if treated with teratogenic medications. Close follow-up of patients with systemic vasculitis by multiple providers may be required to halt disease progression, evaluate response to therapy, and prevention of complications.