The non-Caucasian face has many unique attributes, including skin tone, texture, elasticity, skin thickness, and subcutaneous fat content. These differences may place the patient at increased risk for scarring and pigmentation issues. In this paper, the authors discuss treatment options, surgical and nonsurgical, for rejuvenation of the upper face and midface, including the periorbital region. The selection of the proper treatment must be coupled with a thorough understanding of the age-related changes that occur in the non-Caucasian face to meet and hopefully exceed the patient’s expectations.

In the nineteenth century, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach popularized the term “Caucasian” to describe a distinct group of people from the Caucasus region with specific craniofacial features. Although the Caucasus region lies between Europe and Asia and includes Russia, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Iran, the term Caucasian has since been used to describe those individuals of European origin. Although age-related changes have some similarities between Caucasians and non-Caucasians, there are also some distinct differences. In this paper, the authors discuss treatment options, surgical and nonsurgical, for rejuvenation of the upper face and midface, including the periorbital region. For the purposes of this paper, the term non-Caucasian includes African American, Middle Eastern, and Asian ethnicities.

Facial analysis

The Upper Third of the Face

The ideal eyebrow shape was defined as an arch where the brow apex terminates above the lateral limbus of the iris, with the medial and lateral ends of the brow at the same horizontal level. This definition has been further refined to provide a framework for the analysis of the upper third of the face and subsequent treatment options for forehead rejuvenation. Biller and Kim studied the ideal location of the eyebrow apex in Asian and white women. Their findings suggested that neither the ethnicity of the models nor the ethnicity of the volunteers who analyzed the eyebrow position had a significant role in determining the ideal eyebrow position. A survey of plastic surgeons and cosmetologists regarding eyebrow shape in women by Freund and Nolan found that a medial eyebrow at the level of the supraorbital rim was ideal and that brow lifting techniques tend to elevate the medial eyebrow above this level. Increasing eyebrow height with age has been previously reported, and this phenomenon has been attributed to habitually contracting the frontalis muscle. Therefore, an overly elevated brow may not only result in a surprised appearance but also impart an aged countenance.

During the evaluation of the upper eyelid, the forehead should be assessed for ptosis, as this may confound the diagnosis of upper eyelid dermatochalasis. The surgeon should evaluate the upper eyelid to rule out the contribution of blepharoptosis. The position of the upper eyelid should ideally rest at the level of the superior limbus. If unilateral blepharoptosis is identified, the surgeon must rule out blepharoptosis in the contralateral eye, as Herring’s Law may apply in this situation. The Asian upper eyelid has several distinct anatomic characteristics including low, poorly defined or absent eyelid crease, narrow palpebral fissure, and/or epicanthal fold.

The Lower Lid/Midface Complex

Evaluation of lower eyelid position and laxity is an essential part of the examination. The ideal position of the lower eyelid margin is at the inferior limbus. A snap test and lid distraction test are key components to the evaluation of lower eyelid laxity. A snap test is performed by grasping the lower eyelid and pulling it away from the globe. When the eyelid is released, the eyelid returns to its normal position quickly; however, in a patient with decreased lower eyelid tone, the eyelid returns to its normal position more slowly. The lid distraction test is performed by grasping the lower eyelid with the thumb and index finger; movement of the lid margin greater than 10 mm demonstrates poor eyelid tone and an eyelid tightening procedure is indicated. A Schirmer test is indicated if there is concern about dry eye syndrome. Progressive loss of elastic fibers and collagen organization lead to dermatochalasis (loss of skin elasticity and subsequent excess laxity of lower eyelid skin). In addition, the orbital septum weakens with age leading to steatoblepharon (pseudoherniation of orbital fat). Orbicularis oculi muscle hypertrophy is also associated with age-related changes of the upper and lower eyelid complex.

The tear trough is also known as the nasojugal groove and is defined as the natural depression extending inferolaterally from the medial canthus to approximately the midpupillary line. A hollowness may be present lateral to the midpupillary line and parallel to the infraorbital rim; this has been referred to by various names, including the lid/cheek junction. Various anatomic explanations for the tear trough deformity have been provided in the literature, including an attachment of orbital septum to arcus marginalis at the level of the orbital rim, a gap between the levator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscle and the orbicularis oculi muscle, and loss of facial fat in the tear trough or pseudoherniation of fat superior to the tear trough. The tear trough and lid/cheek junction occur inferior to the orbital rim and arcus marginalis.

Treatment options

Brow/Forehead

Nonsurgical options for brow/forehead

There are several nonsurgical options available for the rejuvenation of the brow/forehead, including neuromodulators, dermal fillers, and autologous fat grafting. For example, Lambros reported volumizing the brow with hyaluronic acid fillers to give more youthful appearance to the brow/periorbital region.

Surgical options and technique for brow/forehead

Many techniques for surgical rejuvenation of the upper third of the face have been described in the literature. Although the open technique via a coronal or trichophytic approach has been the standard with which all other techniques have been compared, our preferred method for surgical rejuvenation of the brow is the endoscopic brow lift. Botulinum toxin injected into the corrugator supercilii and procerus muscles at least 2 weeks before endoscopic brow lift. The combination of chemical ablation of the depressor muscles with botulinum toxin A and myotomy of the depressor muscles during the endoscopic forehead lift acts synergistically not only to maintain the elevated forehead position but also to treat the nasoglabellar furrows. The addition of botulinum toxin may also lessen the chance of return of depressor muscle function compared with myotomy or myectomy alone.

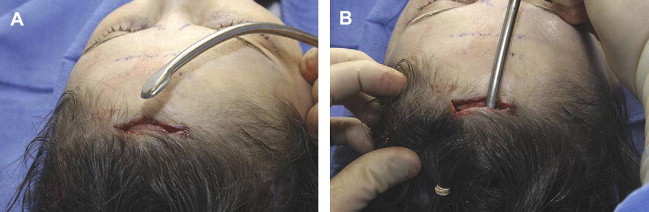

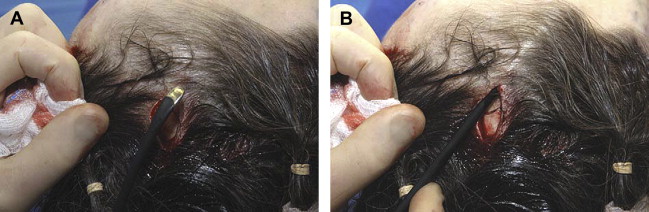

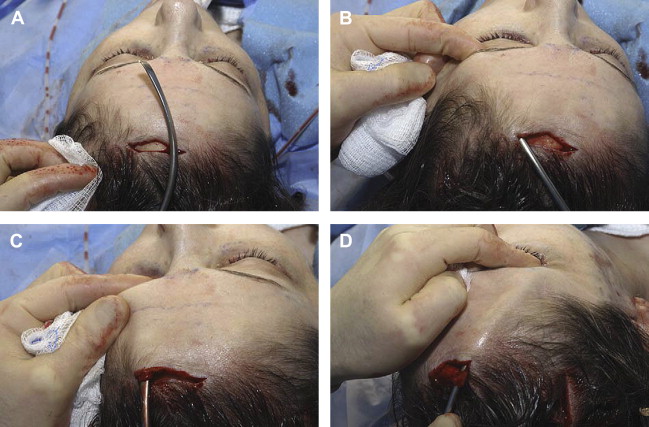

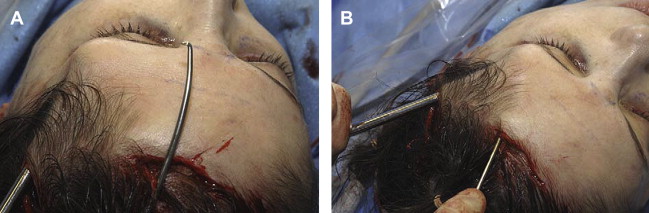

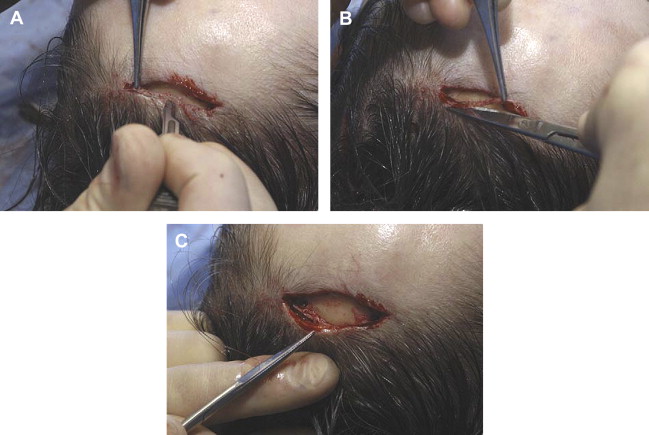

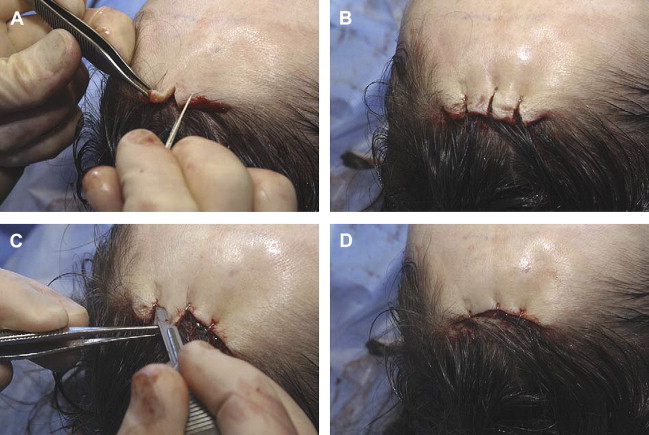

One noticeable effect of the endoscopic brow lift is an elevation of the hairline. Although this is an acceptable result for most patients, persons who have high hairlines (greater than 5 to 6 cm) may not wish to move the hairline more posterior. We perform a technique combining a short 3- to 4-cm trichophytic incision with endoscopic equipment to lift the forehead in patients who present with brow ptosis and high hairlines. This technique includes a trichophytic incision that is approximately 4 cm in length and is made at the midline following the natural irregular frontal hairline contour in a scalloped fashion. Laterally, on each side, a 3- to 4-cm vertical incision is made 2 cm posterior to the temporal hairline recession at a location demarcated by the lateral canthus and temporal line ( Fig. 1 ). Initially, flap elevation is made in a subgaleal plane ( Fig. 2 ). The elevation is performed approximately 5 cm posterior to the incision sites; the posterior elevation not only minimizes the development of scalp rolls but also mobilizes the posterior flap, allowing for closure of the trichophytic incision without elevating the hairline. The temporal region is elevated in a plane between the temporoparietal fascia and the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia, and the conjoint tendon is then divided ( Fig. 3 ). Dissection of this temporal region is performed down to an area slightly superior to the zygomatic arch and lateral canthus. The frontal branch of the facial nerve is protected because the plane of dissection is between the temporoparietal fascia and the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia. Following this, elevation is made in a subperiosteal plane down to a level of 2 cm above the supraorbital rim ( Fig. 4 ) and the arcus marginalis is then elevated. Arcus marginalis elevation is performed with the nondominant hand functioning as a guide to the level of the supraorbital rim and the location of the supraorbital foramina ( Fig. 5 ). This elevation is performed in the region of the glabella down to the nasion. Once the arcus marginalis is elevated, an endoscope is used to provide visualization; and the conjoint tendon is further divided with curved endoscopic scissors (Accurate Surgical & Scientific Instruments Corp, Westbury, NY) down to the level of the sentinel vein ( Fig. 6 ). Care is then taken to identify and preserve the supraorbital neurovascular bundle ( Fig. 7 ). With a custom-made reusable electrode knife tip, the periosteum is incised in a horizontal direction at the level of the supraorbital rim ( Fig. 8 ). Myotomy of the corrugator supercilii and procerus muscles is performed with the electrode knife tip. Because the motor nerve to the corrugator supercilii muscle runs within the substance of the lateral orbicularis oculi muscle, we perform a lateral myotomy of the orbicularis oculi muscle not only to weaken the orbicularis oculi muscle but also to interrupt the innervation to the corrugator supercilii muscle. In an effort to camouflage the trichophytic incision, we not only bevel the incision but also de-epithelialize the posterior flap. A 2- to 3-mm strip of epidermis from the posterior flap is excised ( Fig. 9 ). The anterior flap of the trichophytic incision is lifted up, and vertical incisions are made through the anterior flap. Staples are placed at these positions to approximate the anterior and posterior flaps. The excess skin and soft tissue from the anterior flap are then excised in a beveled manner; the bevel is directed from posterior to anterior ( Fig. 10 ). The staples are then removed and hemostasis is achieved with bipolar electrocautery. Fixation with sutures via bone tunnels of the outer cortex of the skull is performed. The bone tunnels are made with the Browlift Bone Bridge system and drill bit with a 2-mm diameter and 25-mm guard (Medtronic Xomed Surgical Products, Jacksonville, FL). Two bone tunnels are created at the trichophytic incision site in a horizontal direction, whereas bone tunnels are created in the vertical direction at the lateral incisions ( Fig. 11 ). Using the drill bit with a 25-mm guard, there have been no instances of cerebrospinal fluid leaks or other intracranial complications. If significant bleeding is encountered from the bone tunnel site, hemostasis is achieved with Bone Wax (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ), and new bone tunnels are created. A 2-0 polyglactin suture (Vicryl) is used for fixation from the bone tunnel to the galea and subcutaneous tissue of the anterior flap to achieve lifting of the medial forehead at the trichophytic incision site. Very minimal lifting is performed medially so that the medial brow may remain at the level of the supraorbtial rim. The lateral forehead is lifted with the suture from the bone tunnel to the galea and the subcutaneous tissue at the most anterior aspect of the lateral incision on both sides ( Fig. 12 ). This suture not only lifts the lateral forehead but also reapproximates the edges of the lateral incision. The lateral incision is closed with staples. The trichophytic incision is closed in a layered fashion ( Fig. 13 ). With meticulous closure, the trichophytic incision is well camouflaged ( Fig. 14 ).

Upper Eyelid

Treatment of the non-Caucasian upper eyelid depends on several factors, of which ethnicity is paramount. Is the non-Caucasian individual Asian, Middle Eastern, or African American? Within the Asian population, there are distinct differences in perceived beauty and motivation for rejuvenation of the upper eyelid based on culture and whether that patient is Korean, Chinese, or Japanese. If a natural crease is present in the aging Asian upper eyelid, volume enhancement and conservative excision of excess skin would benefit the patient, whereas a patient who has undergone a previous procedure and who has a surgically created crease may benefit from volume enhancement alone, and a patient without a crease may benefit from double eyelid surgery. Does the patient have a history of keloid formation? If so, a nonincision suture technique for double eyelid surgery may be an option; however, this treatment has a higher relapse rate compared with incision techniques and fixation. Incision techniques have the benefit of addressing the epicanthal fold in the Asian upper eyelid with an epicanthoplasty.

In the non-Asian, non-Caucasian patient, a traditional upper eyelid blepharoplasty is an excellent option to treat upper eyelid dermatochalasis and steatoblepharon. The preoperative assessment of the patient seeking rejuvenation of the upper and/or lower eyelid complex includes a history to evaluate for systemic disease processes, such as collagen vascular diseases and Grave disease, dry eye symptoms, and visual acuity changes. It is important to delineate whether the changes to the upper and/or lower lids are related to age-related changes to the eyelids (dermatochalasis and steatoblepharon) or a manifestation of a systemic process, such as allergy or an endocrine disorder. For example, a patient with Grave disease may have upper eyelid retraction and exophthalmos, but the myxedematous state of hypothyroidism may mimic dermatochalasis. Therefore, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level should be obtained if a thyroid disorder is suspected. If any unusual history is gleaned from the preoperative assessment, it may be prudent to obtain an ophthalmologic evaluation before undertaking blepharoplasty. The limitations of blepharoplasty and the role of adjuvant procedures must be discussed with the patient. For example, the patient seeking periorbital rejuvenation with significant crow’s feet may benefit from botulinum toxin treatment, whereas the patient with fine wrinkling, crepe paper skin may achieve significant improvement with skin resurfacing.

Surgical technique for the upper eyelid

The surgeon must be meticulous in the surgical markings for upper eyelid blepharoplasty prior to surgery as a difference of 1 to 3 mm (mm) from one eyelid to the next may create noticeable asymmetries. Therefore, the surgical markings for both upper eyelids are made using a fine tip marker and small calipers. With the patient looking up, the supratarsal crease is identified and measured from the eyelid margin using small calipers; this denotes the location of the inferior limb of the surgical marking. This measurement ranges from 8 to 12 mm from the lid margin (10–11 mm in women; 8–9 mm in men) ( Fig. 15 ). The inferior limb of the marking is curved gently and parallels the lid margin; the inferior limb of the marking is carried medially to within 1 to 2 mm of the punctum and laterally to the lateral canthus. If the marking is carried along the curve of the eyelid crease lateral to the lateral canthus, the final closure scar line will bring the upper eyelid tissue downward, thus resulting in a hooded appearance. In an effort to avoid this unsightly result, the marking sweeps diagonally upward from the lateral canthus to the lateral eyebrow margin ( Fig. 16 ). This modification of the lateral incision makes it easy for women to camouflage the incision with makeup. Medially, the nasal-orbital depression should not be violated as an incision in this area may result in a webbed scar; ending the incision medially within 1 to 2 mm of the punctum avoids this result. Next, the superior limb of the surgical marking is made. This is facilitated by using smooth forceps to pinch the excess amount of upper eyelid skin so that the lashes roll upward ( Fig. 17 ). The surgeon’s contralateral hand is used to reposition the eyebrow superiorly to isolate the perceived contribution of brow ptosis from upper eyelid dermatochalasis. Alternatively, if the patient is undergoing a forehead lift at the same time as the upper eyelid blepharoplasty, the surgeon may elect to perform the forehead lift first and then to measure the appropriate amount of upper eyelid skin excision necessary to provide rejuvenation of the upper eyelid complex while minimizing the risk of lagophthalmos.

Typically, isolated upper eyelid blepharoplasty can be performed under local anesthesia with intravenous sedation. Lidocaine 2% with epinephrine (1:50,000) is infiltrated deep to the skin but superficial to the orbicularis oculi muscle, thus minimizing the risk of ecchymosis caused by the injection of local anesthesia. Stabilization of the skin in the eyelid is paramount to making the skin-only incision of the upper eyelid; therefore, an assistant is required to place tension on the skin. A round-handled scalpel with a #15 Bard-Parker blade is ideal for following the curves of the surgical markings in the upper eyelid. Once the skin incision is made, the skin is then sharply dissected from the underlying orbicularis oculi muscle with the blade or dissecting beveled scissors. The preseptal orbicularis oculi muscle is then evaluated. If it is atrophic or very thin, then the muscle need not be excised; however, most often, a thin strip of preseptal orbicularis oculi muscle is excised medially, thus exposing the fat compartments. If the muscle is robust, then the excision is performed along the entire length of the eyelid.

Attention is then directed to the pseudoherniation of orbital fat. If there is fullness of the upper eyelid, a conservative approach to removal of fat is followed to avoid a hollowed or sunken appearance to the upper eyelid. A small opening is made in the orbital septum overlying the middle and medial fat compartments. Gentle pressure on the globe reveals redundant fat from each compartment. Using Griffiths-Brown forceps, the herniated fat is grasped from its respective compartment; and, unless the patient is under general anesthesia, the fat is infiltrated with local anesthesia to minimize discomfort associated with subsequent electrocautery and excision of the redundant fat ( Fig. 18 ). Meticulous hemostasis is of utmost importance not only to maintain a clear operative field but also to minimize the risk of postoperative bleeding. Once fat removal from both compartments is completed, bipolar electrocautery is used to ensure hemostasis before wound closure.