■ Tissue expanders are selected preoperatively based on the width of the patient’s breast. There are many different tissue expanders to choose from, but most are textured and anatomic, providing lower pole projection. Some are taller than they are wide, some are wider than they are tall, and some are semicircular or crescentic and focus on lower pole expansion. Most have integrated metal ports that are located with magnets, although a remote port is useful when placing the expander under a thick flap (such as a latissimus dorsi flap in an obese patient). In such patients, finding the port with a magnet can be difficult and a long needle is required, placing the expander at risk for rupture.

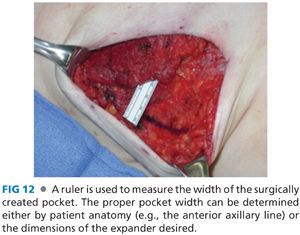

■ Intraoperatively, a ruler is used to measure the width of the surgically created implant pocket, which ultimately determines the expander to be used. Alternatively, one can create a pocket wide enough to accommodate the desired expander. The author’s preference is to measure the surgically created pocket based on native patient anatomy and choose an expander that is 1 cm narrower in width.

■ Prior to the exchange procedure, the patient is again marked in the standing position. The midline is marked and asymmetries in implant position are noted. The ideal contour for the final implants is marked.

■ Final implants are selected primarily based on volume, although width should be taken into consideration. A full discussion of implant types is beyond the scope of this chapter. The majority of surgeons use smooth, round, high-profile implants for reconstructive purposes, although textured anatomic silicone implants may gain popularity if or when they gain U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. Patients with very wide chests may require a moderate-profile implant that will have a larger base diameter for a given volume (although less projection). A comparison of saline versus silicone implants is also beyond the scope of this chapter, but suffice it to say that the issue is controversial. The author’s preference is to offer both types to patients noting the following advantages and disadvantages for each implant type:

■ Saline

■ Advantages: Implant rupture is immediately detected; removal of a ruptured implant is simple and quick.

■ Disadvantages: Reexpansion may be required if implant ruptures and is not replaced expeditiously; firmer than silicone, although this difference is diminished when good soft tissue coverage is present; higher potential for rippling if underfilled.

■ Silicone

■ Advantages: Softer, more “natural” feel

■ Disadvantages: Rupture is often clinically silent until extracapsular rupture and silicone granuloma formation is present, removal of a ruptured implant is a difficult operation that often involves removal of native tissue thus compromising subsequent reconstruction, and monitoring for silent implant rupture using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not proven and has a definite risk of false positives and unnecessary surgeries.

Positioning

■ Patients are placed in the supine position under a general anesthetic with arms padded circumferentially and abducted at 80 degrees. Following mastectomy, the patient is positioned such that the sternum is parallel to the floor.

TECHNIQUES

TISSUE EXPANDER PLACEMENT

First Step—Wound Assessment

■ Following mastectomy, the wounds are irrigated and hemostasis is obtained. The mastectomy flaps are evaluated by examining their thickness and assessing color and capillary refill. Areas where dermis is exposed internally should be carefully evaluated externally. Areas where the external skin is pale without capillary refill should be considered for debridement. Laser-assisted indocyanine-green fluoroscopy has been promoted to assess mastectomy flap perfusion; however, guidelines for its use and interpretation have not been firmly established.1

■ Use of tumescent solution by the extirpative surgeon makes assessment of mastectomy flaps difficult and has been shown in some studies to be associated with a higher rate of mastectomy flap necrosis.2–4

■ When there is significant concern for mastectomy flap necrosis, or if debridement of questionable tissue will lead to closure under tension or an open wound, then aborting reconstruction is strongly advised.

■ If necessary, the IMF can be recreated with interrupted suture; however, the position of the inferior edge of the expander will ultimately determine the IMF, which can be adjusted further during an exchange procedure if desired. Some surgeons try to establish the native IMF during this initial procedure (which may make the exchange procedure simpler), whereas others intentionally place the expander lower than the IMF to increase lower pole expansion and projection (which requires recreation of the IMF with suture during the exchange procedure). The author’s preference is to preserve the native IMF when performing single-stage implant reconstruction, when placing a significant initial fill volume in the expander, or when the IMF is already low. When performing delayed two-stage implant reconstruction or when placing minimal initial fill volume in the expander, placing the implant below the IMF will preferentially expand the lower pole and permit the surgeon to create minimal ptosis at the exchange procedure (as described in the following text).

Second Step—Creation of Implant Pocket

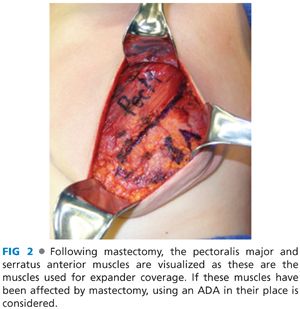

■ The tissue expander cannot be covered by the mastectomy flaps alone, which are thin and offer poor soft tissue coverage. Ideally, the surgeon should provide complete musculofascial coverage with the pectoralis major and serratus anterior muscles (FIG 2), or use an acellular dermal allograft (ADA) or other product in addition to the pectoralis major muscle.

■ The lateral edge of the pectoralis major muscle is pinched between the surgeon’s index finger and thumb and pulled away from the chest, revealing a loose areolar plane between the pectoralis major and minor muscles. Dissection in this plane commences with Bovie cautery, but once the subpectoral space is entered, much of the superior and medial implant pocket can be created via blunt digital dissection before using lighted retractors for direct visualization. A lighted retractor is quite helpful to finish medial dissection, as great care must be taken to ligate or cauterize the intercostal perforators of the internal mammary vessels (FIG 3).

■ The medial boundary is defined externally by the preoperative markings that define the patient’s native breast form. Internally, it is quite common to release the medial and inferomedial origins of the pectoralis major muscle. It is important not to release this area excessively, as symmastia can result and is difficult to correct.

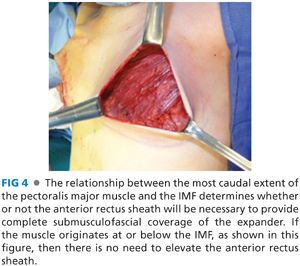

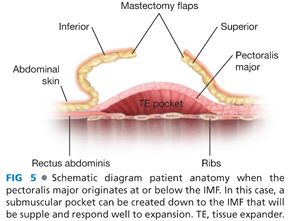

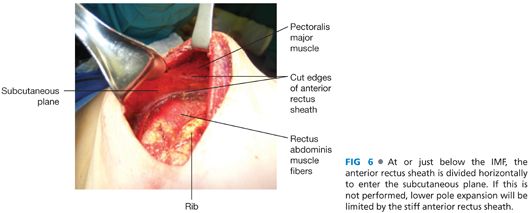

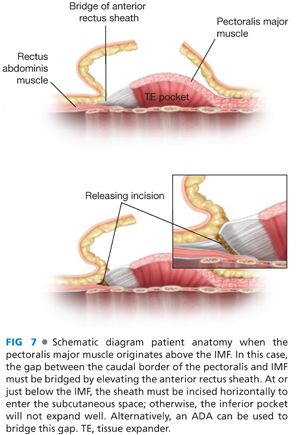

■ After the subpectoral plane is developed, the inferior insertion of the pectoralis major muscle is examined (FIG 4). If the patient’s muscle reaches the IMF, then a submuscular pocket can be created down to the IMF with supple and adequate soft tissue coverage that will respond well to expansion (FIG 5). More commonly, however, the pectoralis major inserts above the IMF. In this scenario, to provide autologous implant coverage inferiorly, one must continue dissection past the pectoralis major insertion and under the anterior rectus sheath until just below the IMF. Transitioning from the subpectoral plane to underneath the anterior rectus sheath is sometimes technically difficult and may result in a few gaps in coverage that can be closed after the pocket is fully created. A lighted retractor is necessary for this portion of the procedure. The anterior rectus sheath is quite stiff and will not expand well unless an incision is made transversely across the sheath just below the IMF, entering the subcutaneous plane (FIGS 6 and 7). If the anterior rectus sheath is released above the IMF, one would obviously enter the implant pocket. The goal is to provide complete and supple submusculofascial coverage without gap between the pectoralis major and the IMF. Alternatively, the pectoralis major can be released from the chest wall and a piece of ADA (or other product) can be sewn to the IMF inferiorly and the cut edge of the muscle superiorly.

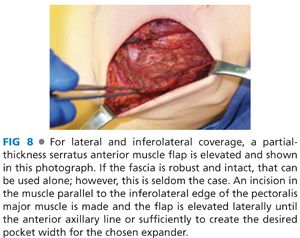

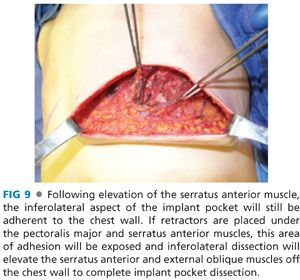

■ Following creation of a subpectoral pocket with or without elevation of the anterior rectus sheath, inferolateral coverage must be provided. Autologous coverage is provided by elevating the serratus anterior fascia if robust, or a partial thickness muscle flap if the fascia is thin or traumatized from the mastectomy. An incision in the serratus anterior is made at the level of, and parallel to, the inferolateral edge of the pectoralis major muscle and a fascial or musculofascial flap is elevated to the anterior axillary line (FIG 8). Alternatively, one can determine the width of the implant pocket based on the width of the desired tissue expander and stop lateral dissection when a sufficient pocket width is achieved (usually 1 cm wider than tissue expander). At this point, the inferior and lateral dissections will be complete, but the inferior serratus and superolateral external oblique muscles will still be attached to the chest wall. By retracting inferiorly and laterally, this plane is exposed and the muscles can be elevated off the chest wall to open the inferolateral pocket (FIG 9).

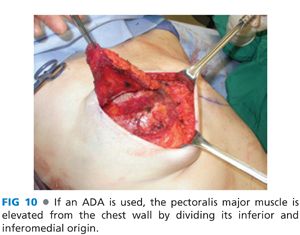

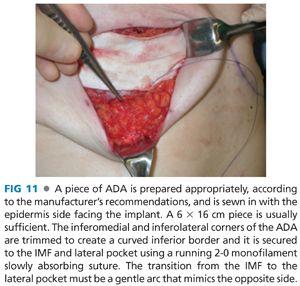

■ If an ADA is used, the origin of the pectoralis major is taken down starting inferolaterally and extending medially and then superiorly along the sternal origin to approximately the 3rd or 4th rib (FIG 10). The ADA will provide inferolateral implant coverage and there is no need to elevate the serratus anterior. In this case, the IMF and anterior axillary line are marked internally and the ADA is sutured along a line that transitions in an arc from the IMF to the anterior axillary line (FIG 11). Alternatively, one can mark the lateral mammary fold based on the width of the desired tissue expander and suture the ADA to this line (FIG 12). One can tailor the surgically created IMF to match the contralateral native IMF during unilateral reconstruction. If performing bilateral reconstruction, then it is imperative to create symmetric IMFs.

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree