Tumors

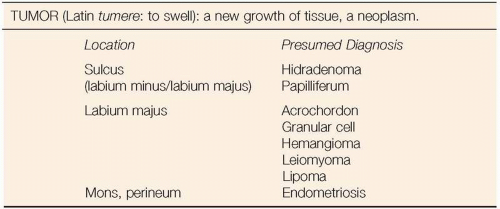

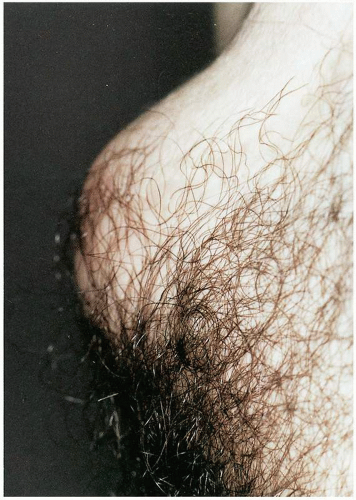

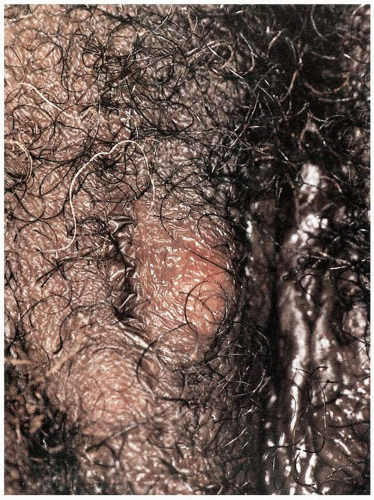

Figure 7.2. Fibroepithelial polyp (acrochordon) with typical papule appearance, similar to intradermal nevus. Excision confirmed diagnosis. |

DEFINITION

Fibroepithelial polyps are a benign polypoid tumor of the vulvar skin with a variable stromal and epithelial component thought to arise from a regressing nevus.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

An acrochordon is usually asymptomatic, noted by the patient only on palpation or visual examination. Smaller examples are occasionally referred to as skin tags. These benign tumors typically arise in hair-bearing skin and are often present for several of years before excised. They may occasionally enlarge sufficiently to result in formation of a giant acrochordon. Blood supply to the giant acrochordon may be compromised and ulceration may occur.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis is suspected on visual inspection. The polypoid structure appears fleshy and may feel like an empty sac. The smaller acrochordon may resemble an intradermal or dermal nevus. The soft consistency of the acrochordon assists in differentiating it from the typical firm condyloma acuminatum that may also appear as a polypoid vulvar lesion. Ultimately the final diagnosis depends on histologic confirmation.

MICROSCOPIC FINDINGS

Acrochordons (fibroepithelial polyp) are composed of a fibrovascular, collagen-rich stroma with a definable stalk that contains prominent thin-walled vessels running parallel to the long axis of the stalk. The polyp is covered with a keratinized epithelial surface that may be thickened, with acanthosis, papillomatosis, and hyperkeratosis, or thinned and atrophic appearing. The epithelium may be folded, with an irregular, undulating surface. The acrochordon may be composed primarily of epithelial or stromal elements, with the larger examples being predominately stromal. The stroma consists of loose bundles of collagen and contains thin-walled vessels. In some cases the stroma is edematous and may be hypocellular. The stromal cells are usually relatively uniform; however, some nuclear pleomorphism may occur and, in rare cases, moderate to marked atypia may be seen. Inflammation is minimal unless there is erosion or ulceration of the epithelial surface. In such cases the inflammation typically involves the superficial subepithelial stroma.

THERAPY

The small asymptomatic acrochordon does not require excision, unless concern exists about the final tissue diagnosis. Many patients request removal because the acrochordon creates a sense of discomfort. A laterally situated acrochordon may interfere with restrictive elastic bands on undergarments. The giant acrochordon will create obvious problems, with mere presence of a large lesion between the thighs resulting in discomfort while walking. Excision may be accomplished in the office setting after placing a ligature around the base of the acrochordon. The base may be injected with a local anesthetic before placement of the ligature. Large specimens may require excision and suture of the excision site.

PROGRESSIVE THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS

Progressive therapeutic options are as follows:

No therapy is necessary for the acrochordon that has been present for years without symptoms.

Office excision of the symptomatic acrochordon for therapy and histologic confirmation of diagnosis.

DEFINITION

Endometriosis is the ectopic implantation of endometrial glands and stroma.

GENERAL FEATURES

Endometriosis of the vulva is almost invariably secondary to implantation of fragments of endometrium in incisions such as episiotomies. It is a rare occurrence and is often enigmatic because episiotomy is a routine procedure performed with many vaginal deliveries.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

A patient with endometriosis of the vulva usually presents with cyclic enlargement and discomfort noted at the site of implantation. She will have a history of a prior childbirth and an episiotomy or will have a history of cesarean section (or hysterectomy) and will complain of suprapubic swelling and localized discomfort in the surgical incision. Although endometriosis of the vulva is usually a well-circumscribed lesion, endometriosis of the mons may be more diffuse and involve subcuticular adipose tissue and fascia.

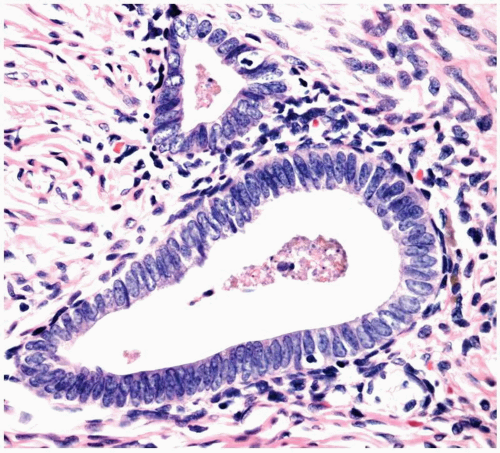

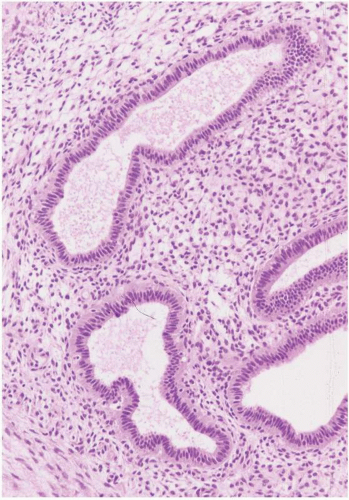

MICROSCOPIC FINDINGS

The histopathologic features of endometriosis are as seen in other sites. Both endometrial glands and stroma are normally found, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages may be evident. The endometriosis may be within scar tissue, resulting in a firm, nodular, blue-black mass. In such cases, foreign body giant cells containing polarizable suture material are often found. Endometriosis may be primarily in the superficial dermis, with a thinned overlying squamous epithelium. In such cases, cyst formation may occur within the endometriosis. The cyst contents are typically brown to black and slightly mucoid. Pregnant patients, or patients who have had progestin or antigonadotropin therapy, may have only a remaining endometrial stromal component, which may have decidual change. In such cases decidualized stromal cells

and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are the only findings and are considered consistent with endometriosis when identified.

and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are the only findings and are considered consistent with endometriosis when identified.

ADJUNCTIVE STUDIES

If the patient complains of hematochezia and the endometriosis is in the perineum, consideration should be given to direct visualization of the lower gastrointestinal tract to rule out transmural endometriosis. Similarly, urinary symptoms in patients with endometriosis should prompt endoscopic evaluation of the bladder.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

A firm, indurated region of endometriosis may be difficult to differentiate from infiltrating carcinoma or a chronic infectious process. Superficial implants of endometriosis in the perineal body may be confused with an epidermal inclusion cyst or vestibular cyst.

CLINICAL BEHAVIOR AND TREATMENT

Endometriosis of the vulva is not a pharmacologic disease; it is a surgical disease, provided symptoms warrant

removal. Small lesions of endometriosis may be removed in the clinic. Any suspicion of rectal mucosal involvement will require more extensive surgery, often necessitating sphincter repair and rectal wall repair. This is more easily accomplished after a bowel preparation and after appropriate anesthesia (general or regional). Endometriosis involving the mons usually requires significant resection in the operating room, and any suspicion of bladder involvement should prompt appropriate preoperative assessment of bladder integrity. If endometriosis is extensive and surgical resection appears to have been suboptimal, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy may be given monthly for 3 months postoperatively to enhance absorption of residual endometriosis.

removal. Small lesions of endometriosis may be removed in the clinic. Any suspicion of rectal mucosal involvement will require more extensive surgery, often necessitating sphincter repair and rectal wall repair. This is more easily accomplished after a bowel preparation and after appropriate anesthesia (general or regional). Endometriosis involving the mons usually requires significant resection in the operating room, and any suspicion of bladder involvement should prompt appropriate preoperative assessment of bladder integrity. If endometriosis is extensive and surgical resection appears to have been suboptimal, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy may be given monthly for 3 months postoperatively to enhance absorption of residual endometriosis.

PROGRESSIVE THERAPEUTIC OPTION

The progressive therapeutic option is:

1. Excision for diagnosis and treatment is indicated.

Figure 7.8. Granular cell tumor in the right labium majus. This had been removed 9 years before and had recurred recently in the same location. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree