Figure 22-1 Primary syphilitic chancre. The epithelium is eroded, and the corium contains a dense, plasma-cell-rich infiltrate. There is neovascularization, with secondary necrotizing vasculitic changes manifested by mural fibrin deposition.

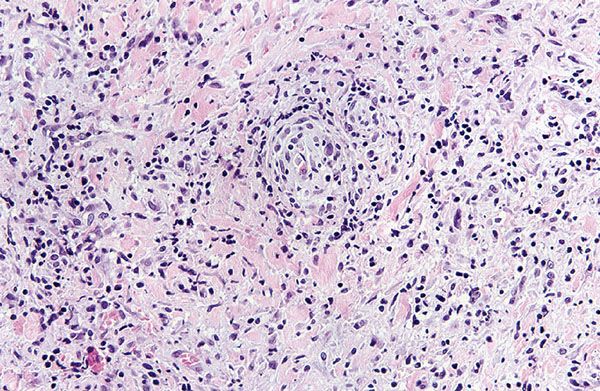

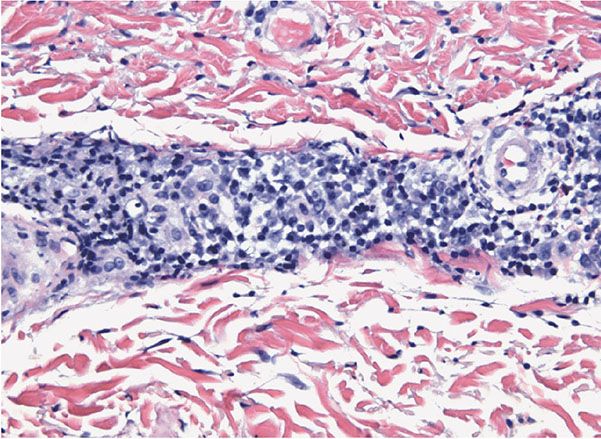

Figure 22-2 Primary syphilitic chancre. There is endarteritis obliterans manifested by endothelial cell swelling, endothelial hyperplasia, and expansion of vessel walls by edema and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with resultant lumenal attenuation. A diffuse extravascular plasma-cell-rich infiltrate is present.

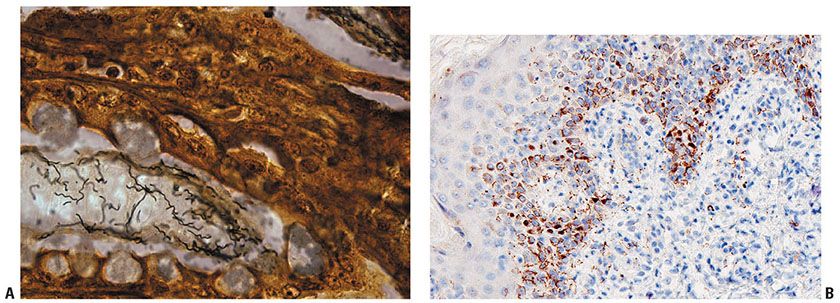

By silver staining with the Levaditi stain or the Warthin–Starry stain and by immunofluorescent techniques, spirochetes are usually identified along the dermal–epidermal junction and within and around blood vessels. If seen in their full length, which is rare, spirochetes generally show 8 to 12 spiral convolutions, each measuring from 1 to 1.2 μm in length (Fig. 22-3A). It should be remembered that silver also stains melanin and reticulum fibers. Differentiation may cause some difficulties but should be possible based on the fact that the melanin in the dendritic processes of melanocytes has a granular appearance, the granules being thicker and more heavily stained than T. pallidum (28). Reticulin fibers, although wavy, do not exhibit a spiral appearance. Immunohistochemistry with antibodies to treponemal antigens are now available in paraffin-embedded applications (Fig 22-3B). Correlation with serology is prudent; in addition to conventional serology, emerging point-of-care tests for rapid screening for syphilis on serum samples have a sensitivity of 75% to 90% and a specificity of 90% to 99%, while those for whole blood are both less sensitive and less specific (29).

Figure 22-3 A: Treponeme morphology. A silver stain reveals numerous elongate, coiled spirochetes ranging in length from 8 to 12 μm. B: Immunohistochemistry decorates spirochetes in this HIV-positive man with a disseminated papular eruption of secondary syphilis. (Illustration courtesy of Dr. David Elder.)

Histologic examination of enlarged regional lymph nodes in primary syphilis most commonly reveals a chronic inflammatory infiltrate containing many plasma cells with endothelial hyperplasia and follicular hyperplasia. Spirochetes are numerous and can nearly always be identified with the Warthin–Starry stain. In some cases, nonnecrotizing granulomas resembling those of sarcoidosis are found in the lymph nodes (30).

Histogenesis. T. pallidum can be demonstrated by histochemistry or by immunohistochemistry. The latter comprises immunofluorescent methods in frozen (31) or fresh specimens and immunoperoxidase methods employable in fixed tissues (32). By electron microscopy, the organism can be seen in both intra- and extracellular dispositions in the epidermis and dermis (33) and within keratinocyte nuclei (34), fibroblasts (34,35), nerve fibers (36), blood vessel endothelia, and the lumina of lymphatic channels (34). Phagocytic vacuoles of macrophages and neutrophils may contain organisms (37), as may the cytoplasm of plasma cells. Ultrastructurally, the organism is 8 to 16 μm in length with regular spirals, a wavelength of 0.9 μm with an amplitude of 0.2 μm, and a cytoplasmic body 0.13 μm in diameter with tapering ends, all enveloped by a 7-nm trilaminar cytoplasmic membrane (38). The organisms attach to host cells by means of acorn-shaped nosepieces. The contractile motility of the spirochete is mediated by three or four axial filaments that course the length of the cytoplasmic body (39). A paraplastic membrane surrounds these axial filaments in young organisms but is replaced by an electron-dense amorphous substance produced by the host cell as an immunologic response in older spirochetes (36).

Differential Diagnosis. Lesions of chancroid are the most difficult to differentiate clinically from a syphilitic chancre. The characteristic histopathology of chancroid is one of dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrates with a paucity of plasma cells and a granulomatous vasculitis. An epidermal reaction pattern similar to the syphilitic chancre is observed, namely, psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia and spongiform pustulation. A Giemsa or Alcian blue stain reveals coccobacillary forms between keratinocytes and along the dermal–epidermal junction. The infiltrate is composed mainly of T-helper lymphocytes and histiocytes including Langerhans cells (40).

Secondary Syphilis

Clinical Summary. There is considerable histologic overlap among the various clinical forms of secondary syphilis, such as the macular, papular, and papulosquamous types (41). Nevertheless, epidermal changes are least pronounced in the macular type and most pronounced in papulosquamous lesions.

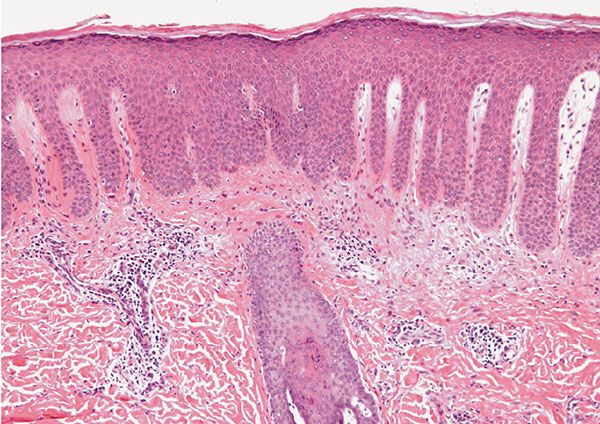

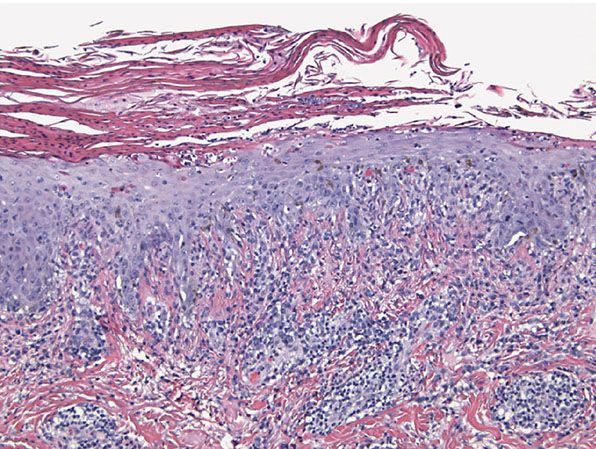

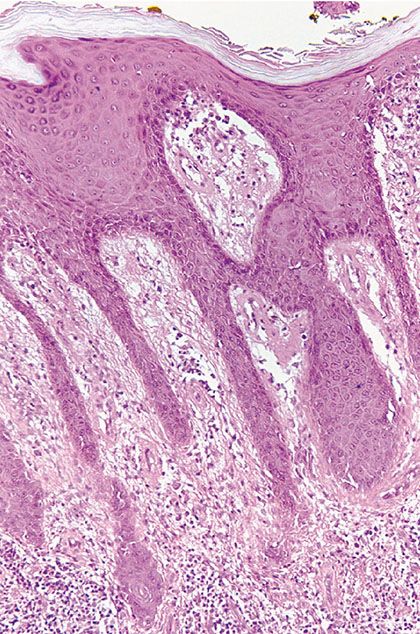

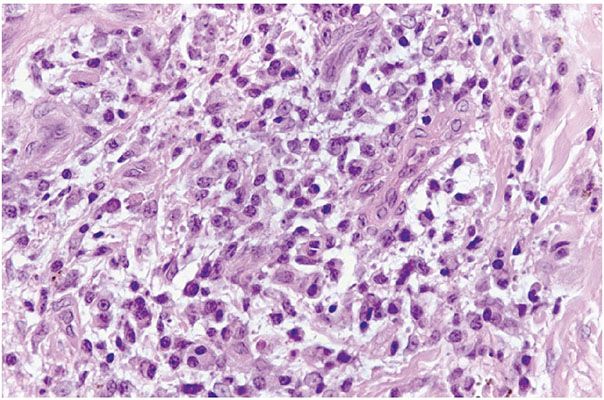

Biopsies generally reveal psoriasiform hyperplasia, often with spongiosis and basilar vacuolar alteration, often with edema of the papillary dermis (Fig. 22-4). Exocytosis of lymphocytes, spongiform pustulation, and parakeratosis also may be observed (28,41). The parakeratosis may be patchy or broad, with or without intracorneal neutrophilic abscesses. Although lesions may mimic psoriasis, attenuation of the suprapapillary plate is uncommon. Scattered necrotic keratinocytes may be observed. Ulceration is not a feature of macular, papular, or papulosquamous lesions of secondary syphilis. The dermal changes include marked papillary dermal edema and a perivascular and/or periadnexal infiltrate that may be lymphocyte predominant, lymphohistiocytic, histiocytic predominant, or frankly granulomatous and is of greatest intensity in the papillary dermis and extends as loose perivascular aggregates into the reticular dermis. Obscuration of the superficial vasculature and lichenoid morphology is observed in some cases, and a cell-poor infiltrate is seen in others. In a few cases, when the infiltrate is heavy, atypical nuclei may be present and may then suggest the possibility of mycosis fungoides (42) or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Neutrophils may permeate the eccrine coil to produce a neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis or manifest as a neutrophil-imbued scale crust (Fig. 22-5) (28). Granulomatous inflammation is almost invariable in lesions of greater than 4 months’ duration and may be present in some cases of early syphilis (43). A plasma cell component is usually present but is inconspicuous or absent in 25% of the cases (Fig. 22-6) (41). Eosinophils are not usually observed. Vascular changes such as endothelial swelling and mural edema accompany the angiocentric infiltrates in half of the cases (41). Necrotizing vascular injury is distinctly unusual. A confirmatory stain is recommended in all cases that are suspected of being secondary syphilis. A silver stain may show spirochetes in about one third of the cases of secondary syphilis, mainly within the epidermis and less commonly around the blood vessels of the superficial plexus. In some instances, the silver stain is positive even when dark-field examination of the patient’s lesions is negative (28). By the immunofluorescent technique, essentially all cases are positive. Phenotypic analysis of the infiltrate reveals a lymphoid populace composed mainly of T cells, with an equal proportion of cytotoxic and T-helper cells.

Figure 22-4 Secondary syphilis. There is striking psoriasiform hyperplasia of an epidermis surmounted by an orthohyperkeratotic and parakeratotic scale. There is prominent papillary dermal edema.

Figure 22-5 Secondary syphilis. There is psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with basilar vacuolopathy and lymphocytic interface dermatitis. The epidermis is surmounted by a parakeratotic scale rich in neutrophils. Plasma cells may be inconspicuous, as in this example.

Figure 22-6 Secondary syphilis. A dense, lymphocytic, and often plasma-cell-rich infiltrate surrounds the cutaneous vessels of the dermis.

There are several histologic variants of secondary syphilis—namely, condylomata lata, syphilitic alopecia, pustular lesions (Fig. 22-5), syphilis cornee, and lues maligna. Lesions of condylomata lata show all of the aforementioned changes observed in macular, papular, and papulosquamous lesions, but more florid epithelial hyperplasia and intraepithelial microabscess formation are observed (28). A Warthin–Starry stain shows numerous treponemes (36).

Biopsies of syphilitic alopecia may demonstrate a superficial and deep perivascular and perifollicular lymphocytic and plasmacellular infiltrate that permeates the outer root sheath epithelium with a concomitant perifollicular fibrosing reaction (28). An involutional tendency characterized by increased numbers of telogen hairs is observed. A concomitant necrotizing pustular follicular reaction may also be seen (20).

An unusual variant of secondary syphilis is lues maligna (44,45), an ulcerative form characterized by severe thrombotic endarteritis obliterans involving vessels at the dermal–subcutaneous junction with resultant ischemic necrosis. A concomitant dense plasmacellular infiltrate with a variable admixture of histiocytes may be observed. Defective cell-mediated immunity may play an integral role in the pathogenesis of lues maligna, particularly in cases in which vascular alterations are minimal (46,47). Several cases of lues maligna arising in the setting of HIV disease have been described, with involvement of the oral cavity as the principal manifestation. A case of secondary syphilis resembling bullous pemphigoid by both light microscopy and immunofluorescent studies has been described (48).

Syphilis cornee/keratoderma punctatum associated with secondary syphilis manifests an epidermal invagination containing a horny plug composed of laminated layers of parakeratotic cells with loss of the granular cell layer and thinning of the stratum spinosum (49). A moderately dense perivascular plasmacellular infiltrate with concomitant capillary wall thickening involves the cutaneous vasculature.

In the rare pustular lesions of secondary syphilis, a necrotizing pustular follicular reaction accompanied by noncaseating granulomata and a perivascular lymphoplasmacellular infiltrate typically characterizes the histopathology (20). A pustular psoriasiform process with an absent granular cell layer and a strikingly thickened cornified layer laced with neutrophils may be seen (Fig. 22-5); if the clinical correlate is rugose or elephantine skin thickening, the designation rupial syphilis may be applied (20).

In addition to small, sarcoidal granulomata in papular lesions of early secondary syphilis, late secondary syphilis may show extensive lymphoplasmacellular and histiocytic infiltrates resembling nodular tertiary syphilis (50). Conversely, lesions of early tertiary syphilis may lack granulomata (51).

Although often nonspecific, the hepatitis of secondary syphilis may produce a granulomatous or cholestatic morphology on liver biopsy; hepatic necrosis and spirochetes may also be observed (52). Syphilis is a cause of reversible nephritic syndrome (53); kidney lesions of secondary syphilis show proliferative changes in the glomeruli (54).

Histogenesis. The renal changes in secondary syphilis relate to immune complexes containing treponemal antigen. Not only has direct immunofluorescence shown granular deposits of immunoglobulin and complement along the glomerular basement membrane (54,55), but indirect immunofluorescence antibody studies using rabbit treponemal antibody and sheep anti-rabbit globulin conjugate have demonstrated treponemal antigen in the glomerular deposits (54).

Differential Diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of lesions of secondary syphilis includes other causes of lichenoid dermatitis, including lichen planus, a lichenoid hypersensitivity reaction, pityriasis lichenoides and connective tissue disease, sarcoidosis, psoriasis, and psoriasiform drug eruptions (28). Prominent spongiosis, suprabasilar dyskeratosis, a mid and deep perivascular component, and the presence of plasma cells are not histologic features of lichen planus or psoriasis (56). Although a mid-dermal perivascular infiltrate, keratinocyte necrosis, and prominent lymphocytic exocytosis are present in pityriasis lichenoides, the infiltrate is purely mononuclear in nature, and neither spongiform pustulation nor plasmacellular infiltration is observed (57). Although lichenoid hypersensitivity reactions and psoriasiform drug reactions may also demonstrate a perivascular infiltrate of plasma cells, tissue eosinophilia is typically observed as well.

Tertiary Syphilis

Tertiary syphilis is categorized into nodular tertiary syphilis confined to the skin; benign gummatous syphilis principally affecting skin, bone, and liver; cardiovascular syphilis; syphilitic hepatic cirrhosis; and neurosyphilis. In the first variant, the granulomas are small and may be absent in rare cases (51). The granulomatous process is limited to the dermis, with scattered islands of epithelioid cells admixed with a few multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. As a rule, necrosis is not conspicuous. The vessels may show endothelial swelling (47).

In benign gummatous syphilis, the main pathology, irrespective of the organ involved, is one of granulomatous inflammation with central zones of acellular necrosis. In cutaneous lesions, the blood vessels throughout the dermis and subcutaneous fat exhibit endarteritis obliterans along with angiocentric plasmacellular infiltrates of variable density involving the dermis and subcutaneous fat.

In cardiovascular syphilis, elastic tissue fragmentation and reduplication with neovascularization and fibrosis of main arteries occurs. Neurosyphilis includes an asymptomatic form—meningovascular syphilis—and parenchymatous syphilis, which is divided into generalized paresis of the insane and tabes dorsalis (58). In meningovascular syphilis, an inflammatory endarteritis involves the leptomeningeal vessels. In generalized paresis of the insane, gliosis with ventricular dilation is observed; spirochetes are identified in the cortex in 50% of the cases. In tabes dorsalis there is demyelinization of the posterior columns of the spinal cord, atrophy of the posterior spinal roots, and lymphoplasmacellular leptomeningitis (21,58).

Principles of Management. Antibiotic therapy is the mainstay of management.

NONVENEREAL TREPONEMATOSES

Yaws (Frambesia Tropica)

Clinical Summary. Yaws is caused by T. pallidum subsp. pertenue, which is indistinguishable microscopically from T. pallidum subsp. pallidum but has been shown to be distinctive by virtue of the substitution of a single nucleotide coding for a 19-kD polypeptide demonstrable by Southern blot analysis (59). Other molecular methodologies confirm distinctive DNA sequences (2,4). Yaws is spread by casual contact between primary or secondary lesions and abraded skin and is most prevalent in warm, moist, tropical climates; 95% of the studied population in one province of Ecuador proved seropositive in one series (60). Some 40% of children proved seropositive in two districts of the Congo in 2012 (61). However, if a patient were treated by antibiotics for infection(s) of another type or types, they might be seropositive but disease-free (62). It is estimated that 2.5 million people globally are affected (63), and in some locations the disease appears resurgent (64). Children are particularly afflicted (65). Sites of involvement include buttocks, legs, and feet. Unlike syphilis, yaws does not manifest transplacental spread to neonates (4). A positive side effect of yaws infection may be the production of antiphosphorylcholine antibodies that may be cardioprotective as they inhibit atherogenesis (66).

Primary Yaws

The initial primary-stage lesion, or “mother yaw,” begins as an erythematous papule roughly 21 days postinoculation, which enlarges peripherally to form a 1- to 5-cm nodule surrounded by satellite pustules covered by an amber crust. A red crusted appearance prompted German physicians to give the appellation “frambesia” to the disease. Lesions may heal as pitted, hypopigmented scars. Fever, arthralgia, and lymphadenopathy may coexist.

Secondary Yaws

Similar constitutional symptoms weeks to months later may herald progression to the secondary stage, characterized by involvement of any or all of skin, bones, joints, and CSF. Skin lesions resemble the “mother yaw” but tend to be smaller and more numerous, hence the designation “daughter yaws.” Periorificial lesions may mimic venereal syphilis. A circinate appearance (“tinea yaws”) may be observed, as may a morbilliform eruption and/or condylomatous vegetations involving the axillae and groins. Macular, hyperkeratotic, and papillomatous lesions may be present on palmoplantar surfaces and may cause the patient to walk with a painful, crablike gait (“crab yaws”). Papillomatous nail-fold lesions may give rise to “pianic onychia.” Relapsing cutaneous disease occurs up to 5 years later, tending to involve periorificial and periaxillary sites. A lifelong noninfectious latent state may then eventuate. Bone lesions consist of painful, sometimes palpable periosteal thickening of arms and legs, occasionally accompanied by soft tissue swellings around the involved small bones of the hands and feet.

Tertiary Yaws

Roughly 10% of cases progress to tertiary yaws, the skin manifestations of which comprise subcutaneous abscesses, ulcers that may coalesce to form serpiginous tracts, keloids, keratoderma, and palmoplantar hyperkeratosis. The bone and joint lesions of this stage include osteomyelitis, hypertrophic or gummatous periostitis, and chronic tibial osteitis, which may lead to “saber shin” deformities. Bilateral hypertrophy of the nasal processes of the maxilla produces the rare but characteristic “goundou,” which obstructs the nasal passages and, if not treated with early antibiotic therapy, may require surgery. Another otorhinolaryngologic complication is “gangosa,” characterized by nasal septal or palatal perforation. Although neurologic and ophthalmologic involvement is not a universally accepted phenomenon, reports of macular atrophy and culture-positive aqueous humor suggest that yaws may exhibit neuroophthalmologic manifestations similar to those of venereal syphilis. A less virulent form of the disease, observed in lower-prevalence areas, is termed “attenuated yaws,” the cutaneous manifestations of which comprise greasy gray lesions in the skin folds.

Histopathology. Primary lesions show acanthosis, papillomatosis, spongiosis, and neutrophilic exocytosis with intraepidermal microabscess formation. A heavy, diffuse, dermal infiltrate of plasma cells, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and granulocytes is observed; unlike the case in syphilis, blood vessels manifest little or no endothelial proliferation (Figs. 22-7 and 22-8) (67). Secondary lesions show the same histologic appearance, resembling condylomata lata in their epidermal changes but differing by virtue of the dermal infiltrate being in a diffuse, as opposed to a perivascular, disposition. The ulcerative lesions of tertiary yaws greatly resemble those observed in late syphilis in histologic appearance (67). The spirochetes can be demonstrated in primary and secondary lesions by dark-field examination. Silver stains demonstrate numerous organisms between keratinocytes. Unlike T. pallidum, which is found in both epidermis and dermis, T. pertenue is almost entirely epidermotropic (67).

Figure 22-7 Yaws, the primary lesion. The biopsy shows a psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis, accompanied by slight spongiosis and an intense lymphohistiocytic and plasmacellular infiltrate in the subjacent corium.

Figure 22-8 Yaws, the primary lesion. The biopsy shows an intense angiocentric lymphohistiocytic and plasmacellular infiltrate without the characteristic endarteritis obliterans vascular alterations observed in syphilis.

Differential Diagnosis. The distinction between yaws and syphilis is based on clinical features; although the location of the organism in a skin biopsy may be helpful, no histologic feature or laboratory test absolutely distinguishes the two diseases (68).

Principles of Management. Antibiotics are the mainstay of therapy for yaws. Widespread use of azithromycin in endemic areas has been proposed to control yaws with an ultimate view to global eradication (69). A single oral dose of azithromycin has been shown to be as effective as an intramuscular penicillin injection (70). Treatment failures occur in as many as 17% of treated patients (71), however.

Pinta

Clinical Summary. Unique among the treponematoses, pinta, caused by T. carateum, demonstrates only skin manifestations (72). The disorder is endemic to Central America and restricted to the Western hemisphere. It affects no age group preferentially and is the mildest of the treponematoses, with hypopigmentation being the only significant sequela. The incidence of pinta is declining precipitously for unknown reasons. Transmission appears to be from lesion to skin, classically between family members; the ritualistic whipping of diseased adults and unaffected youths is the putative mode of transmission in one aboriginal tribe in the Amazon Basin (72).

The primary lesion is characterized by an erythematous papule surrounded by a halo and occurs 1 to 8 weeks postinoculation. By direct extension or through fusion of satellite lesions, the primary site may grow to a diameter of 12 cm, forming an ill-defined erythematous plaque on the legs or other exposed sites. In infants, the primary lesion classically occurs at the sites where the baby was held most closely to the affected mother. The secondary lesions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree