Acne scarring is a common and expected result of moderate to severe acne vulgaris. Given the clinical variety of acne scars and the plethora of treatment options available, management of cutaneous scarring from acne can be challenging and confusing. This article discusses the pathophysiology of acne and acne scarring to better understand its biologic and structural nature. A simple, yet practical classification schema is presented, allowing caregivers to better organize their assessment of acne scarring and develop useful management strategies from this model. This article highlights the various useful laser options that are available for the treatment of acne scarring.

Acne pathophysiology

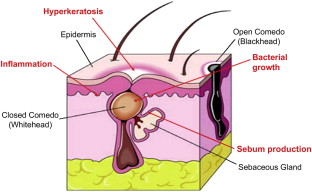

Acne vulgaris, popularly known as acne, is an inflammatory dermatosis of the pilosebaceous unit (ie, the hair follicle and its associated sebaceous gland) and is characterized by the presence of comedones (whiteheads and blackheads), inflammatory papules and pustules, cysts, and nodules. Acne is believed to be caused by the interplay of 4 separate pathophysiologic factors: (1) keratin dysadhesion along the follicular epithelium resulting in the formation of a keratin plug or microcomedone, (2) increased sebum production by the sebaceous gland, (3) bacterial overgrowth, and (4) inflammation ( Fig. 1 ). Trigger factors known to contribute to acne formation include exogenous factors, such as occlusive agents (skincare products, makeup, and so forth), and endogenous factors, such as androgen hormones and specific medications (eg, antiseizure drugs).

Acne vulgaris is by far the most prevalent skin disorder, with more than 80% of adolescents and young adults affected. Almost everyone experiences some form and degree of acne during a lifetime. Unfortunately, when acne resolves, it has a tendency to scar the skin, often creating significant physical and psychological sequelae. An understanding of the nature of acne scarring and the role of modern therapies to reduce its disfiguring appearance can have a positive impact on the quality of life of patients.

Acne scarring pathophysiology

Acne scarring occurs when active acne irreversibly injures the microscopic structure of the skin to the point that its appearance is altered in terms of color, texture, or both. Altered skin texture and color can offer a sharp contrast with surrounding nonscarred skin, attracting attention from the human eye.

Acne scarring is more likely after certain forms of acne vulgaris, with specific skin types, and in particular anatomic locations. Typically, acne scarring is commonly seen after acne that has been characterized by deep inflammation, nodules, or cysts. In these forms of acne, inflammation resulting from follicular rupture and expulsion of sebum, bacteria, and keratin into the dermis of the skin ultimately causes skin surface abnormalities. In some cases, inflammatory injury to the dermis may cause deposition of new collagen that creates uneven surface elevations. In other cases, resolution of cysts and nodules may cause tethering of the skin surface, resulting in small crypts or depressions. Inflammation may also cause injury to pigmented epithelia, causing melanin to be released into the dermis, which results in brown pigmentation. In some postacne individuals, blood vessels may become permanently dilated as part of a wound healing response at the sites of focal inflammation; for an observer, this is perceived as areas of persistent redness.

Patients with darker skin types (Fitzpatrick scale skin types IV, V, and VI) are more prone to acne scarring compared with those who have white skin. Dark-skinned individuals are more prone to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation due to more pigment that may be released into the dermis as the result of skin injury. This is visible as focal and persistent areas of brown pigmentation in areas of prior inflammation. Darker skin types are also more susceptible to the formation of hypertrophic and keloid scars as a result of injury to the skin. It may be that these skin types are genetically more prone to collagen deposition post–skin injury, mediated by the release of profibrotic chemical messengers, such as transforming growth factor β.

Anatomic site of active acne can also predict the likelihood and type of acne scarring that may result. Acne of the forehead and mid to upper cheeks typically results in small icepick scars that may be persistently red in white skin types and brown in darker skin types. Acne of thicker areas of skin, such as the lower face (lower cheeks, chin, and jawline), usually results in larger and deeper scars. Acne of the angle of the jaw, sternal and upper chest, shoulders, and upper back has a tendency to result in hypertrophic and keloid scars. Acne of the lower back tends to yield larger, depressed scars.

Acne scarring pathophysiology

Acne scarring occurs when active acne irreversibly injures the microscopic structure of the skin to the point that its appearance is altered in terms of color, texture, or both. Altered skin texture and color can offer a sharp contrast with surrounding nonscarred skin, attracting attention from the human eye.

Acne scarring is more likely after certain forms of acne vulgaris, with specific skin types, and in particular anatomic locations. Typically, acne scarring is commonly seen after acne that has been characterized by deep inflammation, nodules, or cysts. In these forms of acne, inflammation resulting from follicular rupture and expulsion of sebum, bacteria, and keratin into the dermis of the skin ultimately causes skin surface abnormalities. In some cases, inflammatory injury to the dermis may cause deposition of new collagen that creates uneven surface elevations. In other cases, resolution of cysts and nodules may cause tethering of the skin surface, resulting in small crypts or depressions. Inflammation may also cause injury to pigmented epithelia, causing melanin to be released into the dermis, which results in brown pigmentation. In some postacne individuals, blood vessels may become permanently dilated as part of a wound healing response at the sites of focal inflammation; for an observer, this is perceived as areas of persistent redness.

Patients with darker skin types (Fitzpatrick scale skin types IV, V, and VI) are more prone to acne scarring compared with those who have white skin. Dark-skinned individuals are more prone to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation due to more pigment that may be released into the dermis as the result of skin injury. This is visible as focal and persistent areas of brown pigmentation in areas of prior inflammation. Darker skin types are also more susceptible to the formation of hypertrophic and keloid scars as a result of injury to the skin. It may be that these skin types are genetically more prone to collagen deposition post–skin injury, mediated by the release of profibrotic chemical messengers, such as transforming growth factor β.

Anatomic site of active acne can also predict the likelihood and type of acne scarring that may result. Acne of the forehead and mid to upper cheeks typically results in small icepick scars that may be persistently red in white skin types and brown in darker skin types. Acne of thicker areas of skin, such as the lower face (lower cheeks, chin, and jawline), usually results in larger and deeper scars. Acne of the angle of the jaw, sternal and upper chest, shoulders, and upper back has a tendency to result in hypertrophic and keloid scars. Acne of the lower back tends to yield larger, depressed scars.

Classification and nature of acne scarring

Of the many systems advocated to classify acne scarring, the author uses a unique compiled system based on both color and texture, which he considers the most practical as pertaining to subsequent management ( Box 1 ). When new acne scarring modalities arise, they can be readily added to this classification scheme.

- •

Color

- ○

Normal color

- ○

Red

- ○

Brown

- ○

White (hypopigmented or depigmented)

- ○

- •

Texture

- ○

Normal texture

- ○

Elevated

- ▪

Hypertrophic

- ▪

Keloid

- ▪

- ○

Depressed (or atrophic)

- ▪

Icepick

- ▪

Boxcar

- ▪

Rolled

- ▪

- ○

This classification system has two major categories: color and texture. Every acne scar can be broken down and categorized according to these two components, both of which must be considered and addressed independently to attain improvement of the visible quality of the scar. The elements of a scar’s color and texture must be considered in relative contrast to the surrounding normal skin of the same individual at the same anatomic site. In this classification scheme, there should not be active inflammation. If inflammation exists, it can interfere with understanding the nature of the scar and reduce treatment efficacy. Active inflammation should first be resolved to determine the correct classification of acne scarring. Active inflammation is usually characterized by a purple discoloration, focal elevation of the skin, and tenderness.

Scar Color

For a scar’s color to be considered normal, it must be the same color as the surrounding background skin in the same anatomic site. If a scar is not of normal color, it contrasts with the surrounding background skin in the same anatomic site and can be red, brown, or white.

Scars may appear red due to either persistent inflammation (which is not true scarring and should be eliminated before scar treatment) or permanently dilated small blood vessels (capillaries) beneath the skin’s surface ( Fig. 2 ). Dilatation of blood vessels is part of the skin’s normal healing response to dermal injury, designed to provide oxygen, chemical factors, and nutrients necessary for the skin to adequate recover from the injury. Red blood cells contain hemoglobin, which is red in color. Increased amounts of red blood cells within areas of dilated blood vessels give the skin surface above this area a varying degree of skin surface redness. Deeper and highly concentrated capillaries create a dull red skin surface appearance, whereas superficial and less concentrated blood vessels make the scar appear bright red. Redness within acne scars may be self-limited but can take months to years to resolve.

Brown scars are due to either melanin deposition at the site or hemosiderin pigmentation ( Fig. 3 ). Melanin deposition is often due to the inflammatory injury that acne creates. Seen especially in darker individuals, melanin has the tendency to become incontinent from skin epithelium, depositing into the dermis and creating persistent pigmentation as perceived on the surface by an observer. Skin injury through acne can also stimulate greater melanin transfer to other cells within the skin’s epithelium, contributing to the brown appearance of the scar. Melanin pigmentation may be self-limited but can take months to years to fully resolve.

Hemosiderin is an iron oxide compound that results from extravasated red blood cells at the site of skin injury. When blood vessels are persistently dilated, it becomes more possible for red blood cells and red blood cell fragments to exit the confines of the capillaries that contain them and deposit within the skin’s dermis. If this occurs, the free hemoglobin that results ultimately degrades to release iron constituents that, when combined with tissue oxygen, stain the skin brown. This form of brown scarring is usually more persistent than melanin deposition because hemosiderin exists in small, inert particles that often evade the skin’s clearance system, in many ways similar to the application of a cosmetic tattoo.

White scars are possible, not as part of the natural healing process of acne, but as the result of manipulation from the patient (eg, scratching, pinching the skin) ( Fig. 4 ). It is important to distinguish between scars that are truly white and those that may appear white due to a background of pigmentation (eg, melasma, tanned skin, or sun damage). If there is doubt as to what is normal skin and what is not, a small biopsy may be performed and the specimen treated with a Fontana-Masson stain to identify melanocytes or a Melan-A stain to identify hyperpigmentation. Truly white color in scars is due to either a complete or partial absence of melanin pigment or a thick fibrosis of the skin’s dermis. Melanin pigment may be decreased by inflammation that has completely or partially destroyed the melanocytes that generate melanin. Usually, this is due to a more immune-specific inflammation than is typically seen with acne but more commonly seen with concomitant skin conditions, such as vitiligo. Scarring from chicken pox (varicella) and other inflammatory or fibrotic conditions (eg, lichen sclerosus or morphea) can result in white scars due to destruction of the dermal epidermal junction and underlying fibrosis but is rare in acne vulgaris.

Scar Texture

For a scar’s texture to be considered normal, it must be along the same plane as the surrounding background skin in the same anatomic site. If a difference can be felt in skin texture overlying the scar, it is not considered normal according to the classification scheme. Inflammation and active acne must be resolved to perform scar classification, because inflammation itself can cause textural anomalies and alter the true perception of scar texture.

If a scar is not of normal texture, it contrasts with the surrounding background skin in the same anatomic site and can be either elevated or depressed. Elevated scars can be further classified as either hypertrophic or keloid. Hypertrophic scars are those where the scar tissue has vertical growth only; that is, the lateral confines of the scar do not extend beyond the injury or defect that has initiated the scar. A hypertrophic scar has, by definition, has the same surface area as the inflammatory papule, nodule, or cyst that was its precursor. In contrast, keloid scars have vertical and lateral growth. They are typically more spherical in surface contour and extend beyond the confines of the injury. Keloids are seen more commonly on the shoulders, angle of the jaw, sternal chest, and any areas where there has been cartilaginous injury (such as the ears). Both hypertrophic and keloid scars are the result of excessive collagen deposition at the site of skin injury, the fibrosis of which has elevated the skin surface focally. Although elevated scars may soften or flatten with time, they are not expected to completely resolve without intervention ( Fig. 5 ).

Depressed or atrophic scars occur when the skin contour has dropped beneath the plane of the surrounding skin at the site of skin injury. Depressed acne scars can be classified as (1) icepick, (2) boxcar, or (3) rolled in nature. In icepick scarring, the scar has an acute angle at this base and is usually small (less than 2 mm in width) and superficial (less than 1 mm in depth). Icepick scars typically occur in multiples as a result of focal collagen injury from prior inflammatory acne ( Fig. 6 ). Boxcar acne scars have right angles and therefore appear crateriform in contrast to icepick scars. Boxcar scars may be several millimeters in diameter and can be as deep as 2 mm ( Fig. 7 ). Rolled scars are characterized by shallow, rolled, nonangled borders and can be several millimeters deep. Rolled scars are usually larger in diameter than both icepick and boxcar scars and typically do not occur in clusters ( Fig. 8 ). Rolled scars are the result of a deep cyst or nodule that has involuted or retracted. When cysts or nodules are chronically present in the dermis, adhesions tend to form that affix the lesion in place relative to the surface of the skin. A physical reduction in lesion size results in a tethering of the surface contour directly above the lesion, resulting in the typical rolled morphology. After adhesions have broken down, the skin surface typically takes on a rippled or undulated appearance. Generally, the natural history of all forms of depressed scars is gradual and partial improvement of depth and surface area, but usually not complete normalization of skin contour.

Laser management of acne scarring

Choosing the optimal modality for treatment of an individual patient’s acne scarring depends on a thorough understanding of many factors, including the type and degree of scarring and the anatomy involved as well as the patient’s skin type. Treating clinicians should also consider a patient’s tolerance for procedures and their outcome expectations. The author attributes treatment options according to the type of scarring that is present. The general philosophy is to normalize both the color and texture of individual acne scars to resemble the color and texture of surrounding normal tissue.

Table 1 illustrates various treatment options considered by the author for the various types of acne scarring according to the classification system described previously. Of the various treatment options, this article discusses only the laser options for scar improvement, in particular the usefulness of lasers in normalizing scar color and texture. Thorough knowledge and experience of these laser modalities and their use may lead to creative therapeutic combinations, which may yield faster results with greater improvement. A discussion of multiple modality synergies, however, is beyond the scope of this article.

| Color | Color Treatment Options | Texture | Texture Treatment Options |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | No treatment necessary | Normal texture | No treatment necessary |

| Red |

| Elevated (Hypertrophic and keloid) |

|

| Brown |

| ||

| White |

| Depressed (Icepick and boxcar) |

|

| Depressed (Rolled) |

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree