Mucosal wounds tend to heal more rapidly than skin wounds and with minimal to no scar formation and hence have a minimal impact on function or aesthetics. This is likely due to differences in the magnitude and timing of the various factors that contribute to wound healing. Some examples of these differences are fibroblast proliferation, transforming growth factor-β, macrophages, neutrophils, and T cells. Other factors, such as the moist environment, contribute to the favorable wound-healing characteristics of mucosa.

Key points

- •

Oral mucosal scars are not as functionally or aesthetically significant as facial skin scars.

- •

Oral mucosa heals faster and with less scarring than skin mainly due to differences in fibroblast, macrophage, and neutrophil activity at various stages of wound healing.

- •

Surgical wounding of oral mucosa results in minimal scarring; however, the unique anatomy of the oral cavity makes planning surgical incisions and closure imperative.

- •

Traumatic and ablative wounds of the oral mucosa are more easily reconstructed than facial skin wounds due to the mobility of mucosa, minimal scarring, and the decreased aesthetic exposure as compared with the skin of the face.

- •

Mucosal tissue, specifically buccal mucosa, serves as a predictable donor tissue for reconstruction of soft tissue defects, most commonly the urethra.

Introduction

Wound healing results in a variable amount of scar formation. The resulting scar’s impact on function and aesthetics is greatest on the skin. Mucosal wounds tend to heal more rapidly than skin wounds and with minimal to no scar formation and hence have minimal impact on function or aesthetics.

Most mucous membranes exist throughout the body and serve in various functions, the anatomy of which varies based on its function in that location. Mucosa serves as the epithelial barrier in the gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and respiratory systems. Due to the varied nature of the structure and function of mucosal barriers throughout the body as well as the intent of this text, the focus of this article is scars of the oral cavity mucosa. Inferences may be made to the stratified squamous mucosa of the ocular conjunctiva due to its similar histology and the common scarring diseases (ie, cicatricle pemphigoid) that may affect both oral mucosa and conjunctiva.

Mucosa differs from skin in its anatomy as well as its relatively diminished propensity to scar. Given this fact and its relative lack of aesthetic significance as compared with the facial skin, the necessity of treatment of scars to the mucosa is minimal. However, a review of the differences in the anatomy, physiology, and behavior of mucosa from skin, diseases manifested in mucosa, and the management of incisions and traumatic injuries to mucosa is presented.

Introduction

Wound healing results in a variable amount of scar formation. The resulting scar’s impact on function and aesthetics is greatest on the skin. Mucosal wounds tend to heal more rapidly than skin wounds and with minimal to no scar formation and hence have minimal impact on function or aesthetics.

Most mucous membranes exist throughout the body and serve in various functions, the anatomy of which varies based on its function in that location. Mucosa serves as the epithelial barrier in the gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and respiratory systems. Due to the varied nature of the structure and function of mucosal barriers throughout the body as well as the intent of this text, the focus of this article is scars of the oral cavity mucosa. Inferences may be made to the stratified squamous mucosa of the ocular conjunctiva due to its similar histology and the common scarring diseases (ie, cicatricle pemphigoid) that may affect both oral mucosa and conjunctiva.

Mucosa differs from skin in its anatomy as well as its relatively diminished propensity to scar. Given this fact and its relative lack of aesthetic significance as compared with the facial skin, the necessity of treatment of scars to the mucosa is minimal. However, a review of the differences in the anatomy, physiology, and behavior of mucosa from skin, diseases manifested in mucosa, and the management of incisions and traumatic injuries to mucosa is presented.

Anatomy and function

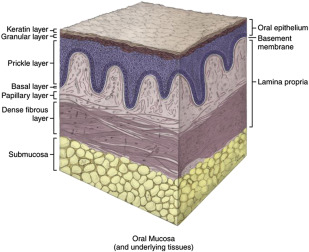

The oral cavity is lined with a continuous layer of mucous membrane that is contiguous with the skin at the vermillion border of the lips and the pharyngeal mucosa. It is predominantly of ectodermal origin and consists of keratinized and nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium.

The specialized mucosa of the dorsal surface of the tongue contains a multitude of epithelial papillae. The lips, cheeks, vestibules, floor of mouth, and ventral tongue consist of lining mucosa ( Fig. 1 ). It has minimal function in mastication and is soft, pliable, and its surface is nonkeratinized epithelium ( Fig. 2 ). The hard palate and gingiva consist of masticatory, or attached, mucosa of keratinized epithelium and have a greater function in mastication.

Like skin, the functions of mucosa are to serve as a protective barrier to mechanical and microbiologic insults; sensation to temperature, touch, and pain; and secretion. The thinness of the floor of mouth mucosa also allows for rapid absorption of medications.

The anatomy of both skin and mucosa are similar. They both contain structurally similar layers. Some nomenclature differs between skin and mucosal histology, such as the dermis of skin is equivalent to the lamina propria of mucosa. The histologic differences between keratinized mucosa, nonkeratinized mucosa, and skin may be seen in Fig. 3 .

Skin Versus Mucosa

Epithelial wounds invariably end in scar formation. Cutaneous scars range from having little or no impact on function and aesthetics to hypertrophic scars or contractures that may interfere with function and aesthetics. The steps of the healing process are similar in both skin and mucosal wounds. However, it has been said that healing of mucosal wounds is akin to that of fetal tissues, with rapid remodeling and minimal scar formation in comparison with wounds of the skin ( Fig. 4 ). In comparison with skin wounds, mucosal wounds exhibit a lower inflammatory response with lower neutrophil, macrophage, and T-cell infiltration, as well as decreased expression of proinflammatory TGF-β 1 .

Environmental differences also exist between skin and mucosa, such as moisture, as a result of salivary flow and microflora. However, histologic studies of skin transposed into the oral cavity show that skin maintains its morphologic characteristics after transplantation. This is clearly seen after the inset of regional or distant cutaneous flaps into the oral cavity with the continuation of hair growth and, in one reported case, the formation of a keloid. These findings imply that the repair in oral mucosa is likely to involve intrinsic characteristics of mucosal tissue and is not only due to environmental factors.

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and more specifically, the TGF-β 1 isoform, is activated in the wound-repair process and promotes inflammatory cell recruitment. Platelets release TGF-β 1 immediately after injury, which recruit collagen-producing fibroblasts. Inflammatory cells continue to produce TGF-β 1 throughout all stages of wound healing. Due to its proinflammatory properties, TGF-β 1 has been implicated as an important factor in scar formation as well as hypertrophic scars and keloids. Studies have shown decreased TGF-β 1 production in oral mucosal wounds as compared with cutaneous wounds, which may contribute to decreased scar formation in mucosa. Another isoform, TGF-β 3 , which has antifibrotic properties, appears to be elevated in oral mucosal wounds as compared with skin wounds.

Keratinocyte function is critical for effective wound reepithelialization for both mucosa and skin. It has been shown that equivalent-sized (1-mm) excisional wounds in oral mucosa completely reepithelialize in 24 hours versus only 25% in cutaneous wounds at 24 hours, suggesting a greater proliferative capacity in oral mucosal keratinocytes over skin keratinocytes. A study by Turabelidze and colleagues also found that 13,710 genes are differentially expressed between the 2 tissues. This finding was unexpected, because the tissues share many histologic and functional characteristics, but it suggests that such dissimilarities may be critical to function. Turabelidze and colleagues observed differential expression of specific proliferation and migration-associated genes in oral and skin epithelium. Several differentially expressed genes might influence keratinocyte migration and proliferation.

One of the major differences between healing skin and mucosal wounds is the phenotypic differences in fibroblasts between the 2 tissues. It may be these differences that make wound healing in mucosa so much faster and with less scarring than cutaneous wounds. In a study by Lee and Eun, the proliferation, contraction, and synthesis of dermal and oral mucosal fibroblasts were compared. They found that oral mucosal fibroblasts proliferated more than dermal fibroblasts; however, the results were not significant. Dermal fibroblasts showed a significantly greater collagen gel contraction than oral mucosal fibroblasts. TGF-β 1 consistently increased the collagen gel contraction. Dermal fibroblasts had a greater response to TGF-β 1 , which resulted in greater contraction. There were no significant differences in basal collagen synthesis between dermal and mucosal fibroblasts, however. Some of the differences in wound healing and scar formation between skin and oral mucosa are probably due not only to differences in the responsiveness of fibroblasts to TGF-β 1 between the tissues, but also the concentration of TGF-β 1 and other cytokines.

In a study using an animal model (red Duroc pig) by Mak and colleagues, large oral mucosal wounds showed the following as compared with similar-sized skin wounds:

- •

Significantly reduced clinical scar formation and wound contraction

- •

Significantly better regeneration of connective tissue organization and reduced histologic scar formation

- •

Decreased number of macrophages

- •

Significantly fewer mast cells at 60 days after wounding

- •

Prolonged presence of increased number of myofibroblasts

- •

Lower density of blood vessels

- •

Lower numbers of TGF-β and pSmad3-positive connective tissue cells

One surprising finding in this particular study was that mucosal wounds showed significantly greater numbers of myofibroblasts as compared with skin wounds. Typically, the prevention of wound contraction results in a less-overt scar, and higher myofibroblast numbers are reported to be associated with scarring. A study by Wong and colleagues showed similar clinical and histologic scar assessment scores in human palatal mucosal wounds as compared with pig palatal mucosal wounds, suggesting that this animal model mimics human wound healing in the palatal mucosa.

Scar-producing disease

A number of local or systemic diseases cause or mimic scarring of the mucosa. Without a history of traumatic or surgical injury to the affected tissue, a differential diagnosis is formulated based on history and physical examination findings. Some examples of diseases presenting as mucosal scarring include submucous fibrosis, basement membrane diseases (ie, pemphigus vulgaris and cicatricial pemphigoid), lichen planus, and proliferative verrucous leukoplakia to name a few examples.

Lichen Planus

Oral lichen planus is a common T-cell–mediated autoimmune disorder in which the resulting inflammation and keratinocyte proliferation results in a variable appearance. Typically, the lesions have the appearance of a leukoplakia; however, an erosive component may be seen ( Figs. 5–8 ). There are reports of malignancy arising from these lesions. Skin lesions may develop in approximately 15% of cases.