Lip and chin scarring occurs owing to reconstruction of congenital, cancer resection, or traumatic defects. Knowledge of lip anatomy and function is critical to optimize results. Realistic expectations should be established before intervention. Scar revision and reconstruction is ideally performed with a subunit approach, placing scars along aesthetic borders and performing subunit reconstruction to camouflage scars. Surgical techniques include direct excision, scar reorientation, local flap rearrangement, pedicled flaps, and regional or free flaps. Resurfacing/adjunctive procedures play important roles in the treatment of scars. This article reviews the anatomy, patient assessment, and techniques used in scar revision of the perioral region.

Key points

- •

An understanding of the anatomy and function of the lips is critical for optimal scar revision and reconstructive results.

- •

Realistic expectations must be discussed with the patient preoperatively.

- •

Key anatomic landmarks should be meticulously realigned. Scars should be placed in borders of the aesthetic subunits and along resting skin tension lines.

- •

Resurfacing may be used to improve the appearance of irregular scars.

- •

Adjunctive therapies such as intralesional injection of corticosteroids or other agents, volume restoration, or botulinum toxin may be necessary to optimize results.

Introduction

Scars arise from a variety of etiologies in the perioral region. Although congenital causes exist, such as residual scarring after involution of a hemangioma, this is an uncommon cause of lower facial scarring. More commonly, treatment of congenital abnormalities such as cleft lip repair or treatment of vascular malformations causes scarring that may need to be revised. Much of the published literature focuses on improving the appearance of upper lip scarring in the cleft lip deformity population, including the need for secondary revision surgery to rectify lip length discrepancies, vermilion deficiencies, and irregularities of the vermilion border. Iatrogenic causes of scarring are also common in adults, primarily owing to resection of malignancy with reconstruction. Facial soft tissue trauma may result in adverse or irregular scarring of the lips or chin regions, with burns posing a particularly complex reconstructive dilemma. This article focuses on the treatment of scars in the lip and chin region.

Introduction

Scars arise from a variety of etiologies in the perioral region. Although congenital causes exist, such as residual scarring after involution of a hemangioma, this is an uncommon cause of lower facial scarring. More commonly, treatment of congenital abnormalities such as cleft lip repair or treatment of vascular malformations causes scarring that may need to be revised. Much of the published literature focuses on improving the appearance of upper lip scarring in the cleft lip deformity population, including the need for secondary revision surgery to rectify lip length discrepancies, vermilion deficiencies, and irregularities of the vermilion border. Iatrogenic causes of scarring are also common in adults, primarily owing to resection of malignancy with reconstruction. Facial soft tissue trauma may result in adverse or irregular scarring of the lips or chin regions, with burns posing a particularly complex reconstructive dilemma. This article focuses on the treatment of scars in the lip and chin region.

Pertinent anatomy

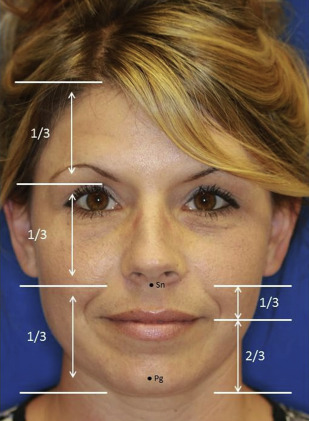

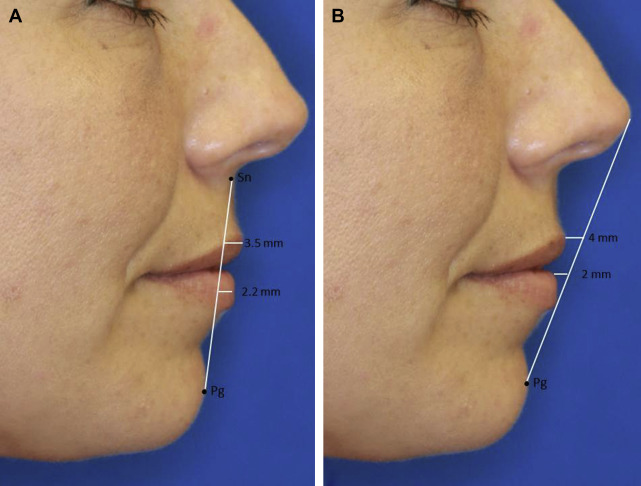

A thorough knowledge of facial anatomy, including that of the lip and chin, is critical for optimal aesthetic and functional outcomes. The perioral region includes the upper and lower lips as well as the chin. It is bordered laterally by the bilateral melolabial and labiomandibular creases and extends superiorly from the subnasale to the menton inferiorly. The perioral region encompasses the inferior one-third of the facial proportions and can be further subdivided with the upper lip accounting for one-third and the lower lip and chin accounting for two-thirds of the lower facial division ( Fig. 1 ). On profile, ideal lip projection is typically characterized as the upper lip extending 3.5 mm and the lower lip 2.2 mm anterior to a line between the subnasale and pogonion ( Fig. 2 A) or the upper lip being 4 mm and lower lip 2 mm posterior to a line drawn between the nasal tip and pogonion (see Fig. 2 B). The ultimate position of the lips depends on the underlying skeletal and dental framework of the patient, aging and volume-related changes, and the muscular apparatus that suspends the lips and baseline skin characteristics.

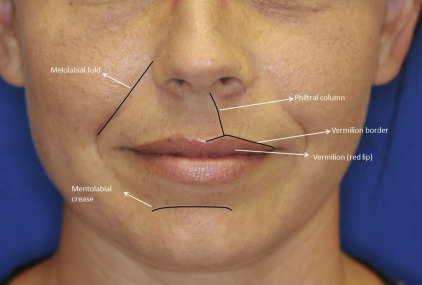

The superficial perioral region incorporates the lip and chin aesthetic regions. The cutaneous lip aesthetic region is further subdivided into aesthetic units, including the paired upper lip lateral units, the philtrum, and the lower lip. The chin subunit extends superiorly from the mentolabial sulcus, the menton inferiorly, and the labiomandibular creases laterally. Key features of the upper and lower lips include the vermilion, which is a modified mucosal lining making up the free margin of the lip. The dry–wet border is the location at which the dry modified mucosal lining meets the wet mucosal lining of the lip. Where the white or cutaneous lip meets the red lip or vermilion is the vermilion border or white roll, which is a key anatomic landmark for reconstruction and scar revision of the lip ( Fig. 3 ).

The lip lining incorporates the white or cutaneous lip and the vermilion externally with the labial mucosal as an internal lining. The bulk of the lip is made up of the orbicularis oris muscle, the fibers of which interconnect at the oral commissures at the modiolus, as well as subcutaneous tissue and minor salivary glands. Other muscles of facial expression insert along the orbicularis or at the modiolus and assist with movement of the lips. The primary blood supply to the lips is from the superior and inferior labial arteries, branches of the facial arteries, which may be located posterior to the orbicularis muscle in a submucosal plane at approximately the level of the vermilion border with branches off these vessels also supplying the chin. The superior and inferior labial arteries are useful for local axial flap reconstruction of the lips. The venous drainage is less well-defined and thought to parallel the arterial supply.

Functional attributes

In addition to the aesthetic implications and sensory function of the lips, there are multiple functional considerations with reconstruction. The mouth and lips are integral to production of facial expressions, provide oral competence during eating and drinking, are critical for proper articulation, and allow for specialized functions such as kissing. Secondary reconstruction including management of scars should aim to restore oral competence and an innervated orbicularis sphincter to maintain proper lip function in addition to providing a cosmetically appealing result.

Patient evaluation

Before undergoing any procedure for scar revision, a complete history and head and neck physical examination should be performed to assess the appropriateness of the patient for a procedure, including the etiology of the scar condition. Comorbidities, including poorly controlled diabetes, immunosuppression, autoimmune or inflammatory disorder, tobacco abuse, history of radiation therapy, status of treatment of existing malignancies, history of keloid or hypertrophic scarring, and history of cold sores, should be identified and considered during treatment planning. A history of prior procedures to improve scar appearance should be acquired. Patient desires should be elucidated and establishment of realistic expectations is paramount before proceeding with intervention.

Subunit organized approach to scar and deformity management

Secondary reconstruction should attempt to maintain all aesthetic, sensory, and motor functions of the lip, similar to primary reconstruction of perioral defects. Scarring of the lip may be minor and treated with small superficial revisions and adjunctive procedures, or include large secondary deformities with volume discrepancy requiring a more extensive reconstruction. In severely contracted scars of the lip with volume deficiency, this may be the optimal option for function and appearance. Full-thickness resection and revision should be performed when necessary and revision may follow published algorithms for defect reconstruction. Briefly, full-thickness defects involving less than 30% the width of the upper or lower lip are considered small and are amenable to primary closure. Defects 30% to 60% the width of the lip are intermediate sized defects and in general require a pedicled cross-lip flap as primary closure will result in microstomia. Finally, large defects greater than 60% lip width will require adjacent flaps from the cheek or free tissue transfer. When full-thickness reconstruction is performed, reestablishing the orbicularis sphincter is critical if at all possible to maintain adequate function.

Similar to other regions of the face, when planning reconstruction or scar revision of the perioral region, it is important to place incisions parallel to relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs) if possible. In the lips, these are radially distributed perpendicular to the orbicularis oris muscle action. Patient age should be taken into account; with aging comes the appearance of static vertical lip lines, muscle atrophy, loss of defining points, and loss of lip volume and lip definition. Therefore, the appearance of scars and need for revision will vary based on age. Whenever possible, scars should be placed along aesthetic unit borders and reconstruction may require excision of remaining uninvolved tissue of an aesthetic subunit to maximize scar camouflage. Finally, meticulous alignment of the vermilion border is critical for minimizing the appearance of scars. An organized approach to scar and deformity management based on a subunit approach will be discussed.

Upper White Lip

Scars of the cutaneous (white) white lip are more apparent when they cross aesthetic units, cause a trap door deformity, exhibit contracture with volume and lip height discrepancies, distort key landmarks (eg, philtrum), are depressed or elevated, are widened, do not have a complete orbicularis sphincter, or are alopecic in males. Many different treatments exist and often a combination of surgical and adjunctive maneuvers is necessary to provide an optimal aesthetic and functional result. Scars with irregular height or thickness compared with the surrounding tissue may be improved with resurfacing techniques alone such as laser therapy or mechanical dermabrasion (discussed elsewhere in this paper). Widened but appropriately oriented scars in RSTLs may be treated with a fusiform excision and revised with meticulous soft tissue handling techniques. If possible, a simple elliptical excision may be performed. For upper lip scars with a large widened area, excision may involve resection of normal surrounding skin, including the entire aesthetic subunit when necessary. Closure should attempt to place the new incision line within the borders of aesthetic subunits, for example, around the alar base or within the melolabial fold ( Fig. 4 provides an example of incision placement for subunit replacement). Larger resections may require adjacent transposition flaps or advancement of surrounding tissue for cutaneous closure. For total upper lip scarring secondary to burns or caustic injuries, cutaneous excision of the entire cutaneous lip aesthetic region with reconstruction by a full-thickness skin graft may be required.

Scars crossing the RSTLs or with minor stepoffs at the vermilion border will benefit from revision using a Z-plasty technique (discussed elsewhere in this paper) to lengthen, reorient, and irregularize the scar. Asking a patient to purse her or his lips will allow for assessment of the status of the underlying orbicularis oris muscle sphincter. Inadequate realignment of the muscle during initial reconstruction may lead to a depressed scar, notching of the lip, or a scar that is more visible with dynamic lip function. In such cases, it is necessary not only revise the scar, but to also address the underlying orbicularis muscle. For upper lip scars that exhibit significant vertical height discrepancies, as may be the case after primary cleft lip repair, complete lip revision and reconstruction with a rotation–advancement technique may be necessary.

Scars with significant contraction involving all layers, severe whistle deformities, as an adjunct in secondary cleft lip revisions, or for a tight lip with limited mobility affecting function, full-thickness wedge resection with layered closure or local flap reconstruction may be appropriate. If necessary, a W- or M-plasty is designed with the wedge resection to avoid crossing aesthetic boundaries.

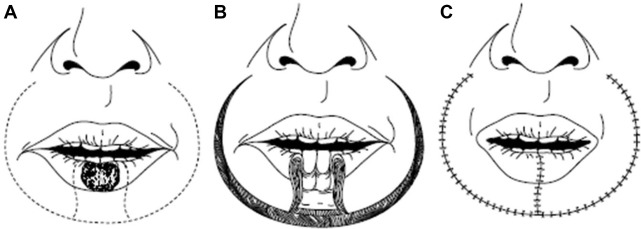

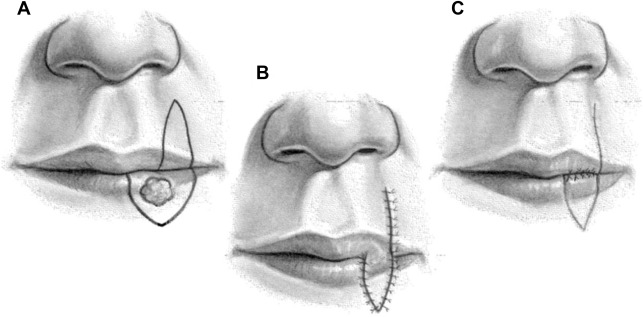

Intermediate-sized defects of the upper lip pose a unique challenge to reconstruct without causing microstomia. If less than one-half of the width of the upper lip, full-thickness bilateral lip advancements may be performed and will require perialar crescentric excisions to allow adequate lateral lip segment mobilization. For defects of the upper lip involving 30% to 60% of the width that do not involve the oral commissure, a full-thickness cross-lip pedicled flap (Abbe lip-switch flap) may be used ( Fig. 5 ). The Abbe or extended Abbe flap is pedicled on the labial artery and designed to fill the unique shape of the defect, with a 1:1 match of defect height but typically 50% of the width to minimize upper and lower lip width discrepancy. The flap is rotated 180° and inset in layers with layered closure of the donor site. After adequate time for vascularization, a second stage procedure to divide the pedicle is performed. Often, this type of flap is combined with additional treatments to provide optimal aesthetic results for scar revision ( Fig. 6 ). For intermediate defects involving the oral commissure, the Estlander cross-lip flap is useful ( Fig. 7 ). This flap is also based on the labial artery and allows for a 1-stage pedicled reconstruction of the lateral lip and commissure. However, it does lead to blunting of the oral commissure with fullness, which may require secondary revision. For near-total or total upper lip defects, more unique flaps should be considered, such as bilateral McGregor or Gilles fan flaps that use adjacent cheek tissue for reconstruction, staged melolabial flaps, pedicled temporoparietal scalp flap, or free tissue transfer.

The Chin and Lower Lip

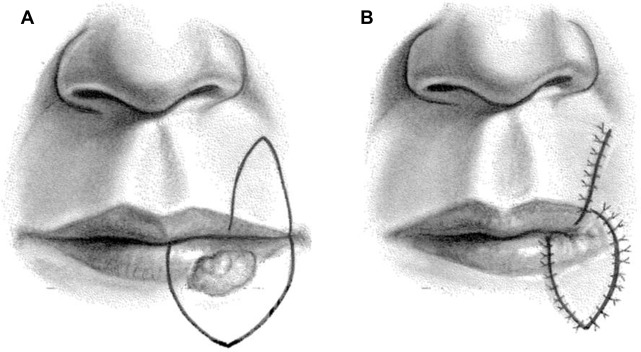

In the lower lip and chin regions, incisions should be placed at the labiomandibular lines and at the labiomental crease. Similar concepts to scar revision and defect management in the upper lip exist for the lower lip. Wedge resections with or without W-plasties are appropriate for excision of scarring or contracture involving less than one-third of the lower lip. For defects up to 50% of the width, bilateral lower lip full-thickness advancement may be performed with good results with the inferior incision designed in the mental crease. As discussed, Abbe or Estlander cross-lip flaps may be similarly used to reconstruct lower lip defects of 30% to 60% of the lower lip. These and defects may also be repaired by one of many flap techniques using tissues from surrounding cheek and lip skin. Partial thickness circumoral rotation–advancement (Karapandzic) flaps that preserve the neurovascular bundles during dissection of facial muscular attachments off the orbicularis oris muscle are a useful technique to reconstruct large defects of the lower lip, and less commonly the upper lip ( Fig. 8 ). This provides an innervated reconstruction that attempts to reestablish the oribicularis sphincter and provide oral competence. The Gilles fan flap and the McGregor modification of the Gilles flap are full-thickness flaps with incisions beginning at the inferior aspect of the defect and narrowly pedicled on the ipsilateral oral commissure to provide a composite lip rotation–advancement flap with a layered closure ( Fig. 9 ). Bilateral flaps may be used to reconstruct large defects and restores the orbicularis muscle sphincter. Blunting of the oral commissure and microstomia will result.