Transposition Cheek Skin Flaps: Rhombic Flap and Variations

J. P. GUNTER

R. W. SHEFFIELD

EDITORIAL COMMENT

The editors commend this flap to you. The detailed explanation of the base geometry unravels the mysteries of the rhombic flap.

Because of the different sizes and shapes of defects, the conditions, availability, and extensibility of surrounding skin, and the proximity of different anatomic structures, there is no single transposition flap to reconstruct all cheek defects. The rhombic flap is frequently used for reconstructing small to moderate-sized cheek defects. Although is not applicable in all cases, an understanding of its basic principles is often helpful in the plan and design of other transposition flaps.

INDICATIONS

The rhombic flap, described by Limberg (1), is the one we use most for reconstructing cheek defects. It has a precise geometric design, and knowledge of its principles helps to understand flap transfer and to plan and execute other transposition flaps.

ANATOMY

Axial-pattern (arterial) flaps are seldom used for reconstructing cheek defects. Random-pattern (cutaneous) flaps are the rule, as there is little concern about their viability because of the favorable blood supply to the cheek skin. Random-pattern flaps of the cheeks are raised at a level that preserves the subdermal vascular plexus, which requires that a layer of the subcutaneous tissue remain on the flap.

The skin of the cheek is richly vascular. Perfusion is mainly through the facial artery, which courses superiorly and medially from the inferior border of the mandible to the nasofacial groove. Other arteries supplying the cheek skin are the transverse facial artery (a branch of the superficial temporal), the buccal branch of the maxillary artery, the infraorbital artery (one of the terminal branches of the maxillary artery), and the zygomatic branch of the lacrimal artery (a branch of the ophthalmic artery).

All the arteries supplying the cheek have corresponding veins that accompany them. The facial vein is the chief vein of the cheek. It lies posterior to the facial artery and follows the course of the artery. It communicates with the ophthalmic vein, which empties into the cavernous sinus, and with the infraorbital and deep facial veins, which communicate with the cavernous sinus through the pterygoid plexus. It drains into the internal jugular vein in the upper neck (2, 3, 4).

FLAP DESIGN AND DIMENSIONS

Transposition skin flaps use tissue adjacent to the defect but from a different plane to effect closure. Such flaps are designed adjacent to the defect so that they share a portion or all of one side of the defect. Although flap shapes may vary, all can be thought of as having two sides, a distal end and a base. If excision of a lesion can be designed in the shape of a rhombus, with adequate margins that do not excessively sacrifice normal tissue, the rhombus is marked around the lesion with two sides parallel to the lines of maximum extensibility of the skin (LME), when possible.

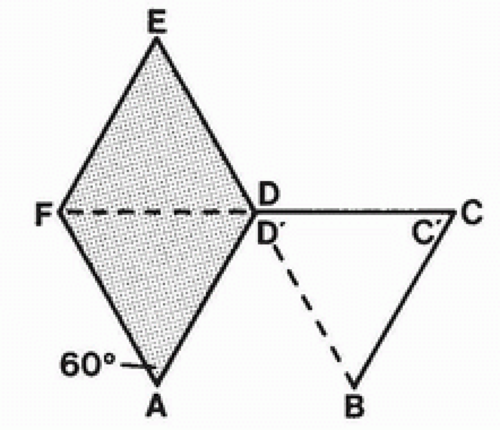

The rhombic flap is designed to reconstruct a 60-degree rhombic defect (1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10) (ADEF in Fig. 99.1). In such a defect, the length of all the sides and the short diagonal are equal (i.e., two equilateral triangles with a common base). The distal end of the flap (D‘C‘) is a continuation of the short diagonal of the defect (FD) and of equal length. The side of the flap next to the defect (AD‘) is also a side of the defect (AD). The side of the flap farthest from the defect (BC‘) is parallel to the near side (AD‘) and equal in length. All sides of the defect and the flap are equal in length.

Four potential donor sites then are mentally pictured (Fig. 99.2), and the site with the most available skin is determined by manual pinching, pushing, and pulling of the skin in these areas. (This is also helpful in assessing the effect donor-site closure will have on surrounding anatomic structures.) The rhombic flap then is drawn in the most favorable area and mentally transposed, checking the direction of the vectors of tension (VOT) and looking for possible problems.

When possible, the flap should be planned so that the short diagonal of the flap donor site (DB) is in the same direction as the lines of maximum extensibility (Fig. 99.3). This facilitates

closure of the donor site by taking advantage of the extensibility of the skin in that direction. We accomplish this by designing the rhombic defect so that two parallel sides are in the same direction as the lines of maximum extensibility. Of the four rhombic flaps possible, two will have their short diagonals in the direction of the lines of maximum extensibility (Fig. 99.4). One of these flaps should be chosen for reconstruction, if there are no contraindications.

closure of the donor site by taking advantage of the extensibility of the skin in that direction. We accomplish this by designing the rhombic defect so that two parallel sides are in the same direction as the lines of maximum extensibility. Of the four rhombic flaps possible, two will have their short diagonals in the direction of the lines of maximum extensibility (Fig. 99.4). One of these flaps should be chosen for reconstruction, if there are no contraindications.

FIGURE 99.1 Sixty-degree rhombic defect with adjacent rhombic flap. All sides of the defect and flap and the short diagonals are equal in length. |

The near corner of the flap base is adjacent to the defect. The far corner is the width of the base away from the defect and serves as the pivot point during transfer of the flap. In the description of the classic transposition flap, the pivot point is assumed to be stationary. This requires that the flap be longer than the defect in order to reach the distal end of the defect when it is transferred (11, 12, 13). In the type of transposition flaps we commonly use, however, the pivot point is advanced toward the defect as the flap is transposed. This facilitates primary closure of the donor site and obviates additional length requirement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree