(1)

Department of Plastic Surgery, University Hospital Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands

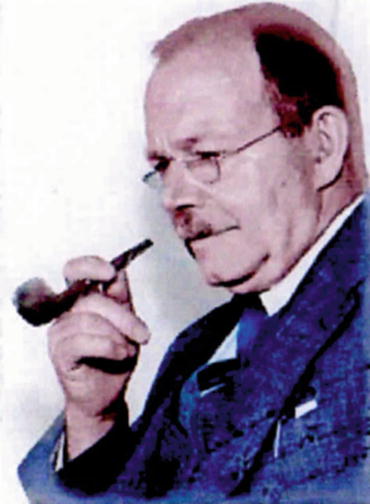

Thomas Pomfret Kilner was born on 17 September 1890, the son of a schoolmaster at Manchester Grammar School. He was educated at Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School in Blackburn, a busy cotton-weaving centre, which lies about twenty miles to the north-east of Manchester. Besides its cotton trade and manufacturing industries, Manchester is well known for its university, and it was there that Kilner studied medicine, winning the Dauntesey Scholarship and the Sidney Renshaw Exhibition, as well as medals in anatomy and physiology on his way to qualifying in 1912, with distinctions in surgery and pathology.

Following 2 years as a demonstrator in anatomy at Manchester University, he became a house surgeon at Manchester Royal Infirmary, with the intention of taking up general practice in Blackburn. But the First World War intervened, and he joined the RAMC, first serving in a Casualty Clearing Station in 1915 and subsequently rising to the rank of Captain as a surgical specialist in No. 4 General Hospital. At the end of the war, he was placed in charge of a fractured femur unit, and having decided upon a surgical career, he was looking for a suitable job when his chief suggested there might be an appointment available in a new specialty: ‘plastic surgery’ with a Major Gillies at the Queen Mary’s Hospital in Sidcup.

So in 1919 began the association that was to last for 10 years until Kilner struck out on his own. The story of Gillies’ remarkable work is told elsewhere, but in Kilner, fate had provided him with an ideal partner, Gillies, the tall and elegant natural sportsman, light-hearted, unorthodox and artistic colonial was the antithesis of the short and portly, single-minded, hard-working and obdurate Mancunian. Both had brilliant minds, affected bristling moustaches and wore half lens spectacles, but there the likeness ended. Some said that had they stayed together, they could have conquered the world but in a sense, they did just that, for in England at least, there never was, nor has been, a partnership which so profoundly influenced the development of any branch of surgery.

With the Great War over, Gillies and Kilner continued the multistage reconstructive facial surgery on the victims of trench warfare at Queen Mary’s Hospital, Roehampton. Gillies set up in private practice, with Kilner as assistant, and following a lean period, their unique work began to speak for itself. Kilner was an extremely dedicated worker and found little time for his hobbies, such as they were, but his chief was happy to escape the rigours of Harley Street, leaving his assistant to slave away whilst he relaxed with his golf clubs or fishing rod. At Sidcup, in the ‘Garden of England’, Kilner found time for beekeeping, but in the 1920s, plastic surgery kept him as busy as those objects of his erstwhile attention. Not only were the two busy in London, but they also travelled about the country to see and treat new patients and one weekend in each month visited Grocott to operate at Stoke-on-Trent.

Much to the disgust of Gillies, when Kilner decided to set up on his own in 1929, he took rooms two floors below Gillies at the London Clinic. It was not until the formation of the British Association of Plastic Surgeons in 1946 that they patched up their differences. However, in his second book, Gillies generously acknowledged the debt he owed to his old assistant. It was largely due to the close teamwork of Gillies and Kilner that plastic surgery in Britain gained a pre-eminent position in Europe and the British Empire.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree