Chapter 10

The Skin and Systemic Disease

OVERVIEW

- Skin changes may be the first sign of an underlying systemic disease.

- Widespread reactive rashes result from underlying infections, medications, connective tissue diseases and malignancy.

- Characteristic skin reactions such as erythema multiforme and erythema nodosum are often associated with underlying diseases.

- Reduced numbers of melanocytes can be genetic or associated with autoimmune disease or hormonal changes.

- Increased pigment in the skin can be associated with hormonal changes or underlying neoplasia.

- Generalised pruritus without a skin rash is a strong indicator of an underlying systemic disease—such as renal/hepatic dysfunction.

- Gastrointestinal disease may be associated with skin conditions such as dermatitis herpetiformis and pyoderma gangrenosum.

Introduction

The skin is the window on underlying systemic diseases as it may give visible diagnostic clues to underlying disease (Box 10.1). Cutaneous manifestations of systemic diseases are numerous and may be one of the first indicators of an underlying illness. Therefore, recognition of these reaction patterns and classic lesions in the skin associated with systemic disease can a valuable aid to rapid and accurate diagnosis (Box 10.2). Systemic diseases may affect the skin in the same way that is affects other internal organs—such as connective tissue diseases (Chapter 9). However, underlying conditions may be associated with skin changes brought about by quite different processes, such as those seen in acanthosis nigricans (AN), dermatomyositis and erythema multiforme (EM).

Box 10.1 Clues to a possible underlying systemic disease

- Rash associated with other symptoms such as joint pains, weight loss, fever, weakness, breathlessness and altered bowel function.

- Rash not responding to topical treatments.

- Erythema of the skin due to inflammation around the blood vessels, which may be migratory or fixed.

- Vasculitis, characterised by non-blanching often palpable purplish fixed lesions which may be painful and blistering.

- Unusual changes in pigmentation or texture of the skin.

- Palpable dermal lesions secondary to granulomas, metastases, lymphoma or deposits of amyloid, and so on.

Many widespread reactive cutaneous reactions are a result of medications taken and are manifested as toxic erythema (Chapter 7). The florid skin lesions associated with HIV vary from severe manifestations of common dermatoses to rare skin infections to exaggerated hypersensitivity reactions to drugs (Chapter 15). Drug rashes and manifestations of HIV are important topics and are addressed in detail in Chapters 7 and 15 respectively.

Box 10.2 Characteristic rashes associated with underlying systemic disease

- Erythema multiforme—herpes simplex virus, mycoplasma pneumonia, hepatitis B/C, borelliosis, pneumococcus (medications).

- Pyoderma gangrenosum—haematological malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, monoclonal gammopathy.

- Erythema nodosum—streptococcal infection, TB, sarcoid, pregnancy, inflammatory bowel disease, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Behcet disease.

- Vasculitis—hepatitis B/C, streptococcal infection, parvovirus B19, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid, inflammatory bowel disease, leukaemia, lymphoma.

Skin reactions associated with infections

Toxic erythema is the term used for a widespread symmetrical reactive rash consisting of maculopapular erythema (Figure 10.1) which looks ‘morbilliform’ (which means measles-like). The rash usually starts on the trunk and then spreads to the limbs and is blanching and may be mildly itchy. Toxic erythema is most commonly triggered by viruses including measles, rubella, Epstein–Barr virus (glandular fever patients given amoxicillin classically develop a toxic erythema), parvovirus B19, West Nile virus, human herpes virus 6 (roseola infantum), flavivirus (dengue), coxsackievirus 4/5 and typhus (Salmonella typhi); bacterial infections such as Scarlet fever (group A Streptococcus), Rickettsiosis (Rocky Mountain spotted fever) and parasitic infections (trypanosomiasis—sleeping sickness) can also result in this widespread reactive rash. No treatment is usually required for these toxic erythema rashes except an emollient and occasionally a mild topical steroid if symptomatic; what is required is management of the underlying disease.

Figure 10.1 Toxic erythema reactive morbilliform rash.

EM consists of lesions that are erythematous macules that become raised and typically develop into characteristic ‘target lesions’ (Figure 10.2) in which there is a dusky red or purpuric/blistered centre with a pale indurated zone surrounded by an outer ring of erythema. The lesions are usually asymptomatic (occasionally painful) and may be few/multiple/diffuse and symmetrical, developing over a few days at acral sites (palms, soles, digits, elbows, knees and face). The rash is thought to result from an immunologically mediated hypersensitivity reaction. Systemic symptoms of the underlying infection usually precede the EM rash by 2–14 days. Involvement of mucous membranes (oral, conjunctival, genital) accompanies the classic cutaneous EM rash (<10% of body surface area) in the so-called EM Major. The most common infectious trigger is herpes simplex virus (HSV 1 or 2), which usually presents with a cold sore on the lip or sores/ulcers on the genitals or rarely herpetic whitlow. Other infectious triggers include Mycoplasma pneumonia (shortness of breath, cough, chest radiograph relatively normal), haemolytic Streptococcus (upper respiratory tract infection), adenovirus, coxsackievirus, Epstein–Barr virus, parvovirus B19, viral hepatitis, borreliosis and Neisseria meningitides. Adverse reactions to medications are also a common trigger for EM (Chapter 7). If possible, treat the underlying disease (e.g. aciclovir, penicillin) and apply topical steroid to skin lesions if painful or blistering; occasionally systemic steroids may be needed. EM can be recurrent with each reactivation of HSV, in which case patients may need secondary prophylaxis with aciclovir and possibly additional azathioprine.

Figure 10.2 Erythema multiforme.

Gianotti–Crosti Syndrome (GCS)—papulovesicular acrodermatitis of childhood is a viral exanthema characterised by sheets of minute erythematous papules which may become vesicular in young children (age <12 years) that are distributed initially on the limbs (elbows/knees/feet/hands) and may affect the face (spares the trunk). Individual erythematous papules may coalesce into clusters of larger patches of erythema and may feel ‘rough’ like sandpaper and usually lasts for several weeks. Viral triggers include enteroviruses, echo virus, respiratory syncytial virus, rotavirus, rubella parvovirus B19, hepatitis B and Epstein–Barr virus. GCS may also be triggered by vaccinations (polio, diphtheria, hepatitis B, measles, influenza, pertussis, swine-flu H1N1). GCS is more common in children with atopic dermatitis (AD). The exanthema settles over a few weeks with simple emollients.

Erythema nodosum (EN) consists of tender/painful subcutaneous erythematous nodules on the shins secondary to a hypersensitivity reaction leading to inflammatory panniculitis (inflammation in the adipose tissue) (Figure 10.3). The lower leg lesions usually evolve over a few days following systemic symptoms such as fever and malaise and last for weeks or months depending on the trigger. Infectious causes of EN include Streptococcus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, TB, histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis and blastomycosis. Other non-infectious triggers include medications, inflammatory bowel disease, sarcoidosis, pregnancy, Behcet and Hodgkin disease. In approximately 50% of cases there is no obvious cause determined. Management involves treating or removing the underlying cause, elevation and compression of the lower legs and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Figure 10.3 Erythema nodosum.

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) consists of single/multiple erythematous expanding rings (annular/figurate/gyrate erythema) usually on the thighs or trunk which are asymptomatic. EAC lesions slowly enlarge to form incomplete/complete rings of palpable/macular erythema which may have a slight scale on the inner edge of the ring (Figure 10.4). A hypersensitivity reaction is the current thinking with triggers including Epstein–Barr virus, HIV, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus, Trichophyton fungal infections (tinea), Candida albicans, TB and pubic lice. Other non-infectious causes include underlying leukaemia/lymphoma, solid tumours (breast, ovarian, lung carcinoma), medications and other underlying systemic condition such as Graves’ disease and sarcoid.

Figure 10.4 Annular erythema.

Erythema chronicum migrans is a migrating erythema that results from a cutaneous inflammatory response to infection caused by Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease) (Chapter 17).

Sarcoidosis

The underlying aetiology of sarcoidosis remains unknown; however, there are increasing number of researchers who believe that an atypical mycobacterium may be the trigger. Pulmonary and other systemic manifestations of sarcoidosis may occur without cutaneous disease. However, skin disease is a common presenting sign of underlying sarcoidosis in about 40% of patients. The most common skin changes are

- EN, which is often a feature of early pulmonary disease;

- papules, nodules, and plaques, which are associated with acute and subacute forms of the disease (Figure 10.5);

- scar sarcoidosis, with papules;

- lupus pernio with dusky red infiltrated lesions on the nose and fingers.

Figure 10.5 Nodular and plaque sarcoid.

Skin changes associated with hormonal imbalance

Hyperpigmentation is an increase in circulating hormones with melanocyte-stimulating activity that occurs in hyperthyroidism, Addison’s disease and acromegaly. In pregnancy or in those taking oral contraceptives there may be a localised increase in melanocytic pigmentation of the forehead and cheeks known as melasma (or chloasma) (Figure 10.6). It may fade slowly if ultraviolet light is excluded from the affected skin using daily sun block.

Figure 10.6 Melasma.

Hypopigmentation is a widespread partial loss of melanocyte functions with loss of skin colour seen in hypopituitarism and is caused by an absence of melanocyte-stimulating hormone.

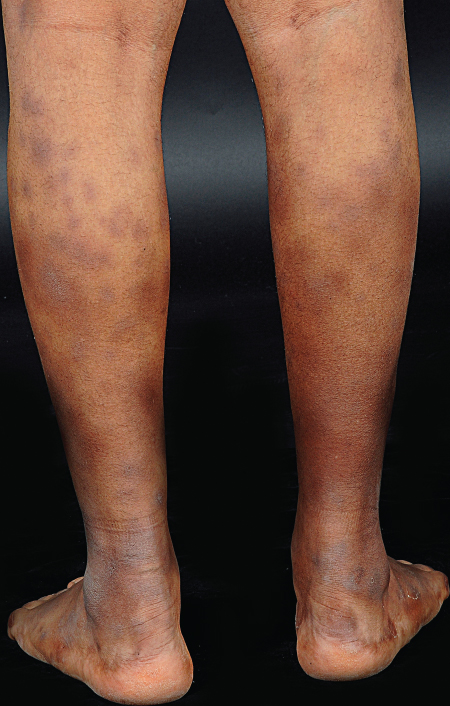

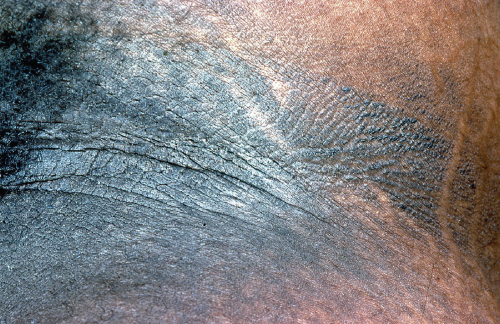

Acanthosis nigricans AN is asymptomatic velvety thickening of the skin characteristically affecting the posterior and lateral aspects of the neck, axillae and arm flexures (Figure 10.7); it appears as dark symmetrical plaques. The most common association is obesity, and with weight reduction the AN resolves. Syndromic AN is subtyped into Type A, which is associated with insulin resistance in young black women with hirsutism and polycystic ovarian syndrome, and Type B, which is associated with autoimmune conditions such as diabetes, thyroid disease and lupus. Antibodies to insulin receptors may be detected in Type B. More extensive and rapidly evolving AN, particularly involving the lips/tongue/palms may herald underlying malignancy, particularly of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. When the underlying cause is treated, the skin signs of AN usually regress.

Figure 10.7 Acanthosis nigricans.

Diabetes leads to alteration of carbohydrate–lipid metabolism; small blood vessel lesions and neural involvement may be associated with skin lesions such as ‘diabetic dermopathy’ due to a microangiopathy, which consists of erythematous papules which slowly resolve to leave a scaling macule on the limbs. Atherosclerosis with impaired peripheral circulation is often associated with diabetes. Ulceration due to neuropathy (trophic ulcers) or impaired blood supply may occur, particularly on the feet. Diabetic patients have an increased susceptibility to cutaneous infections including staphylococcal, streptococcal, coliforms, Pseudomonas and C. albicans.

Necrobiosis lipoidica

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree