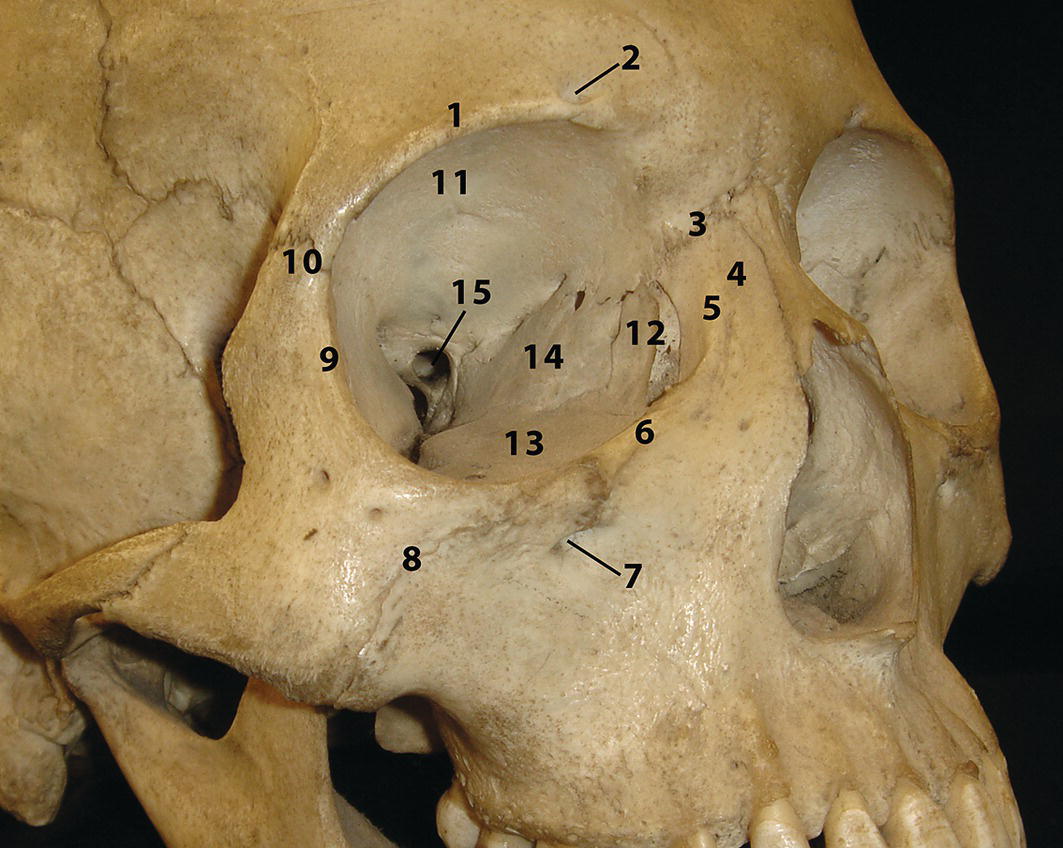

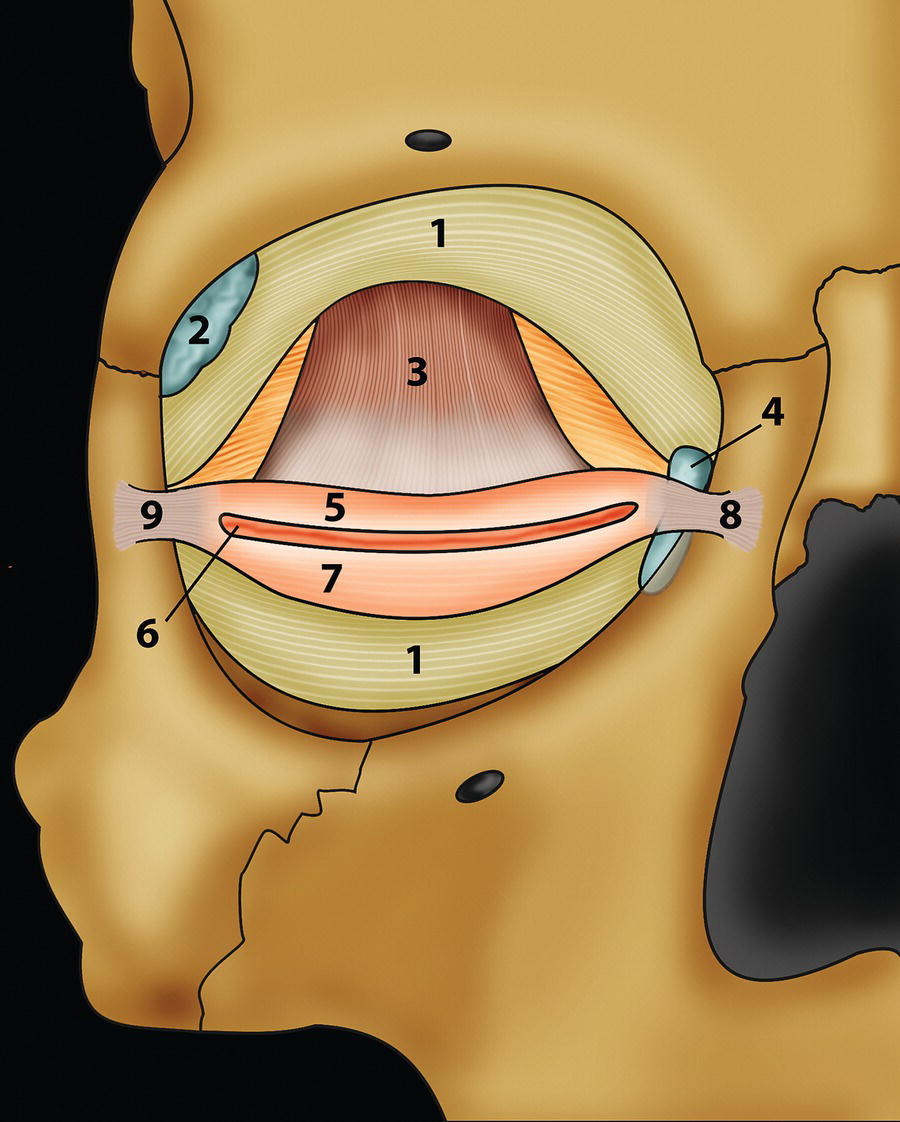

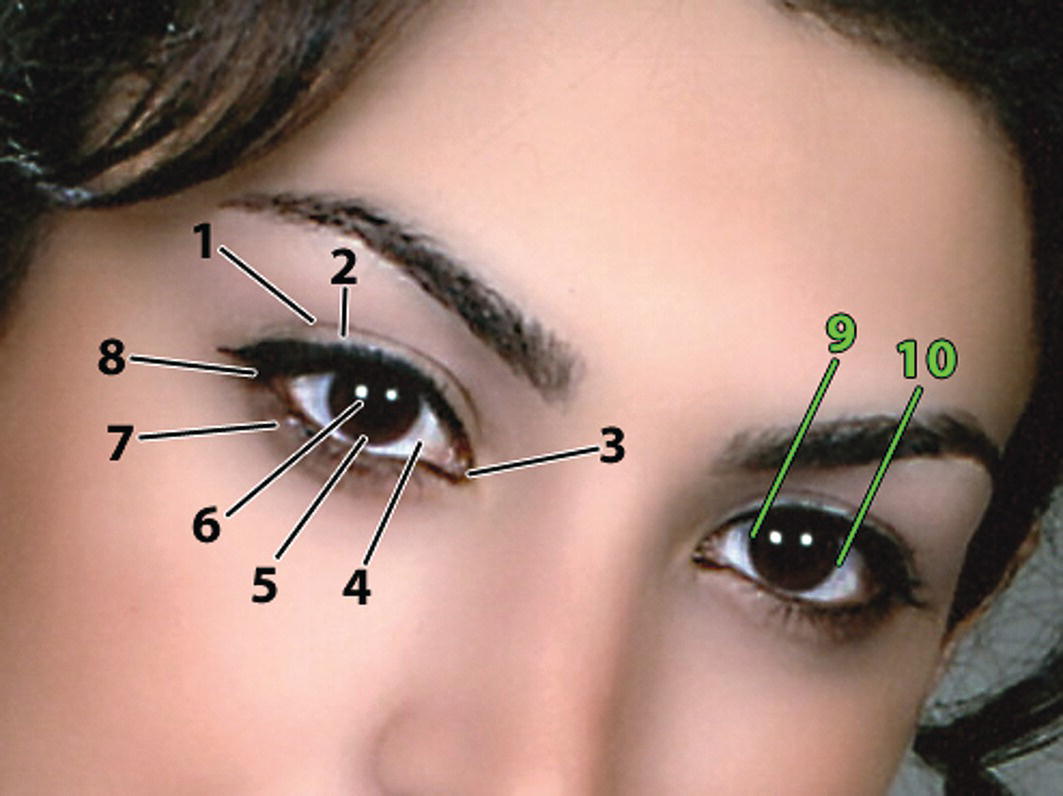

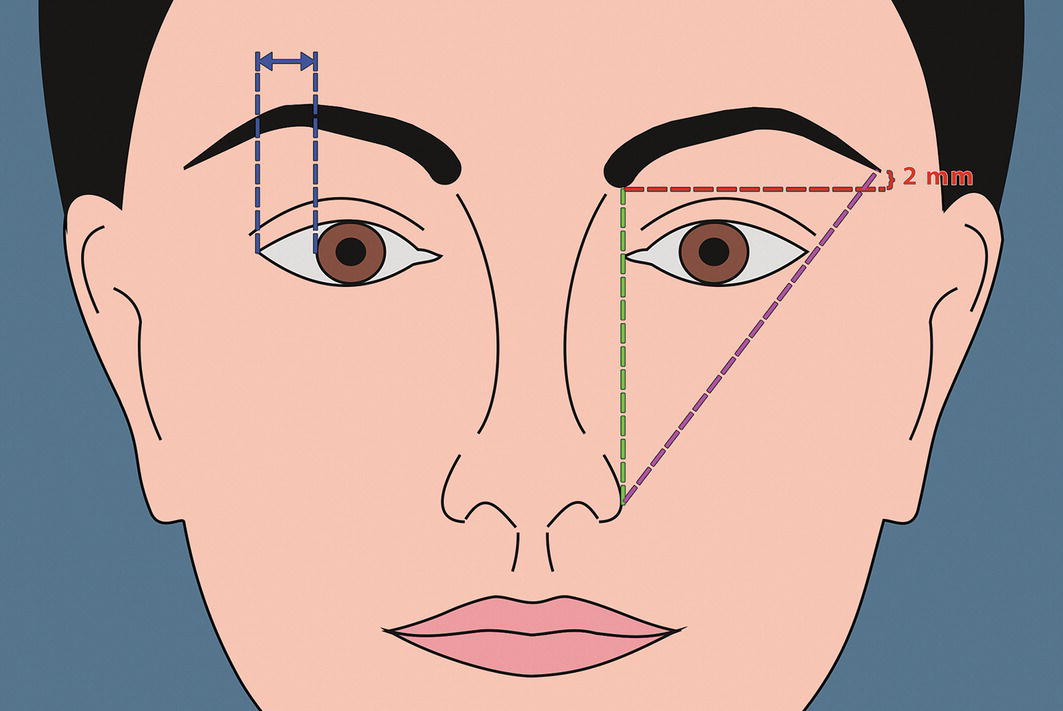

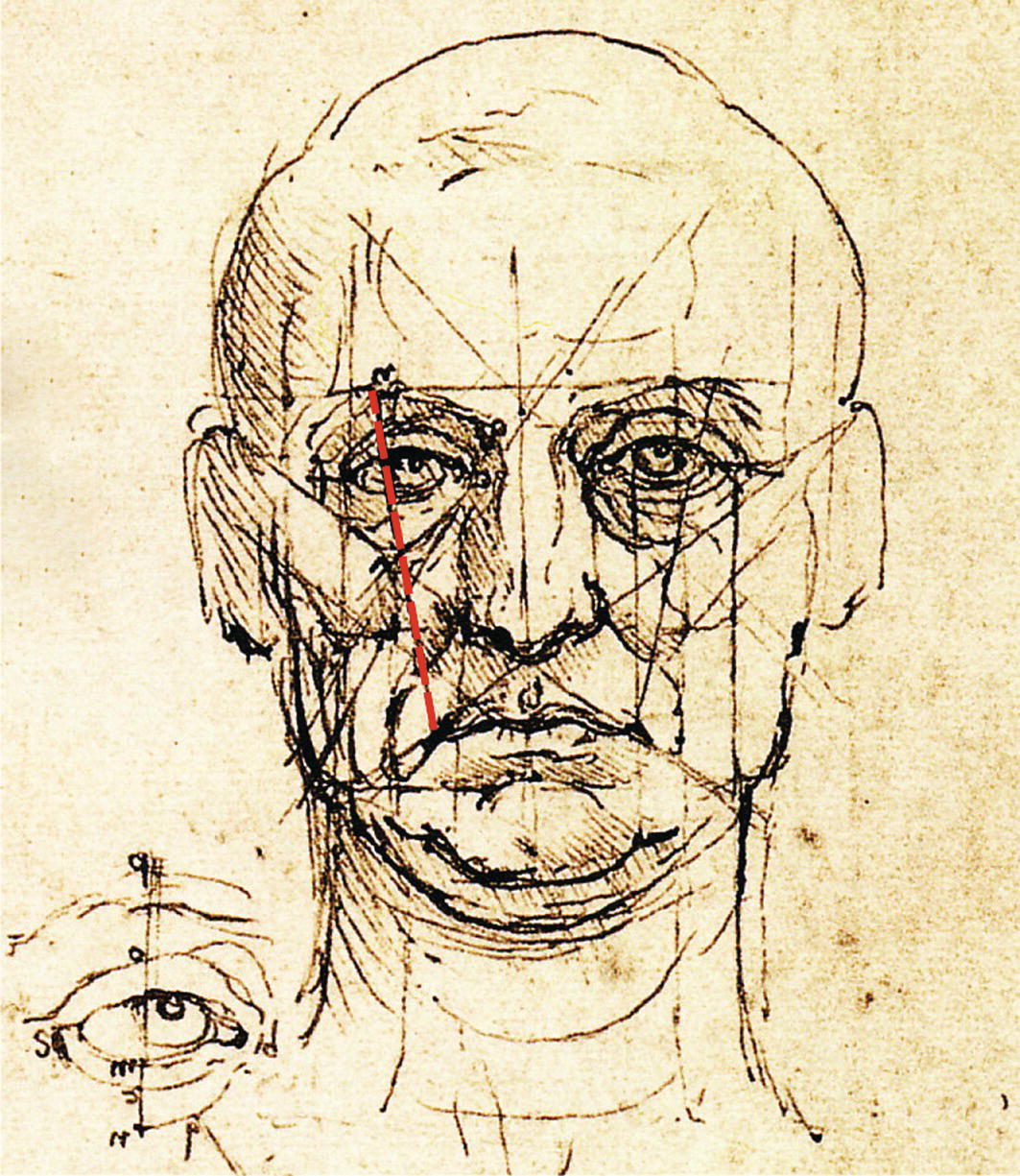

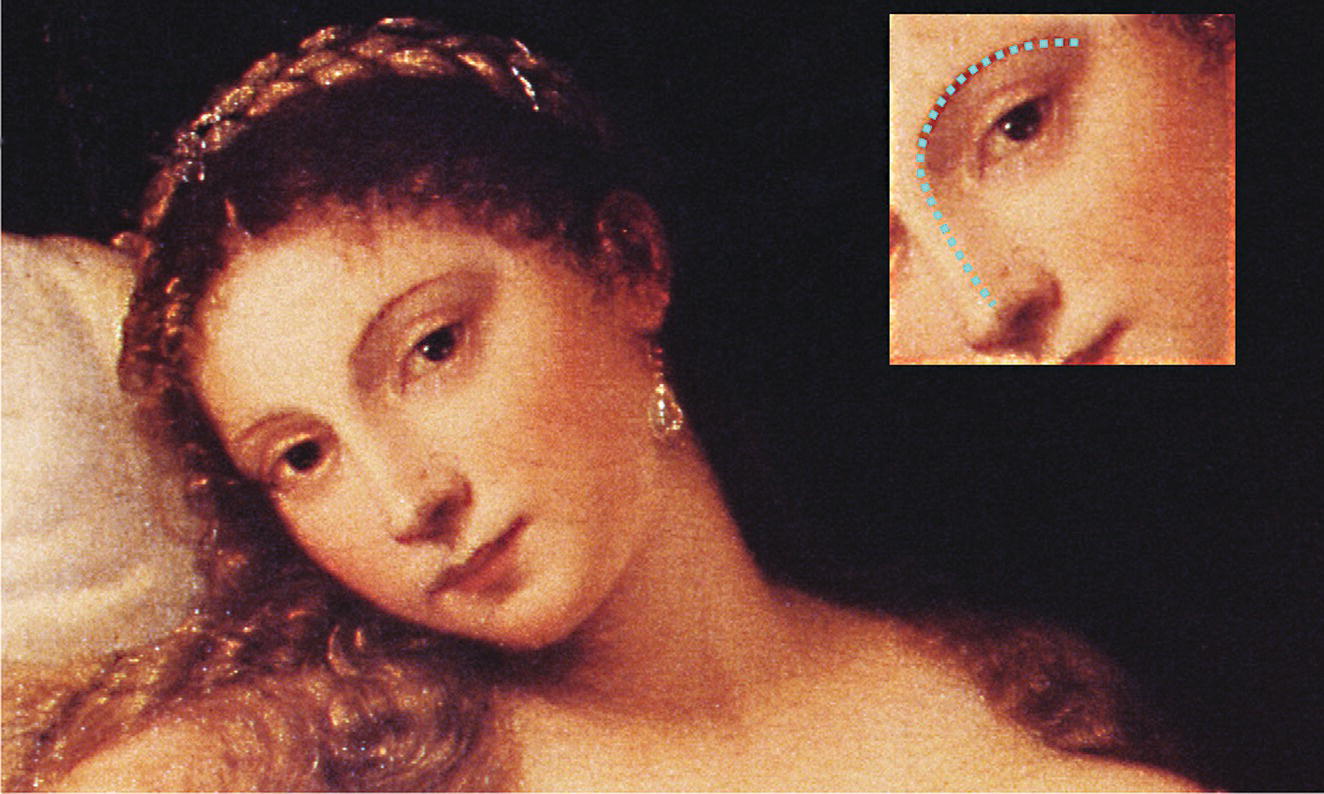

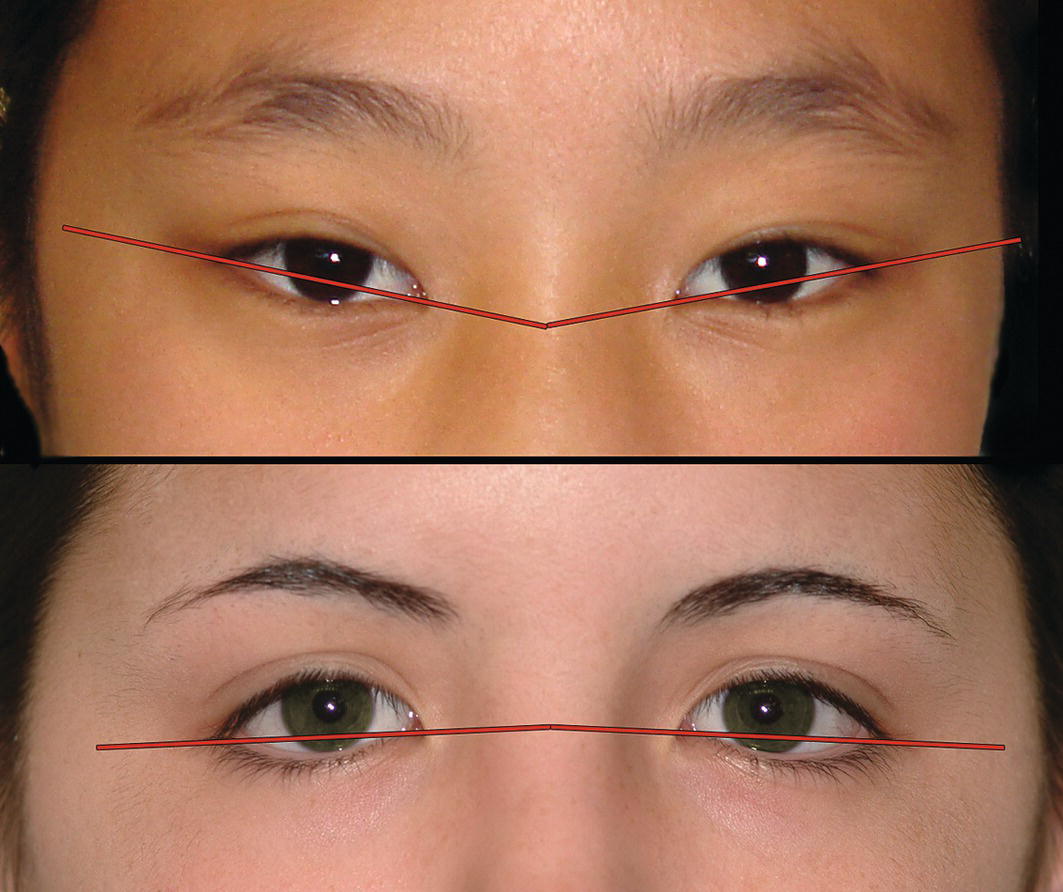

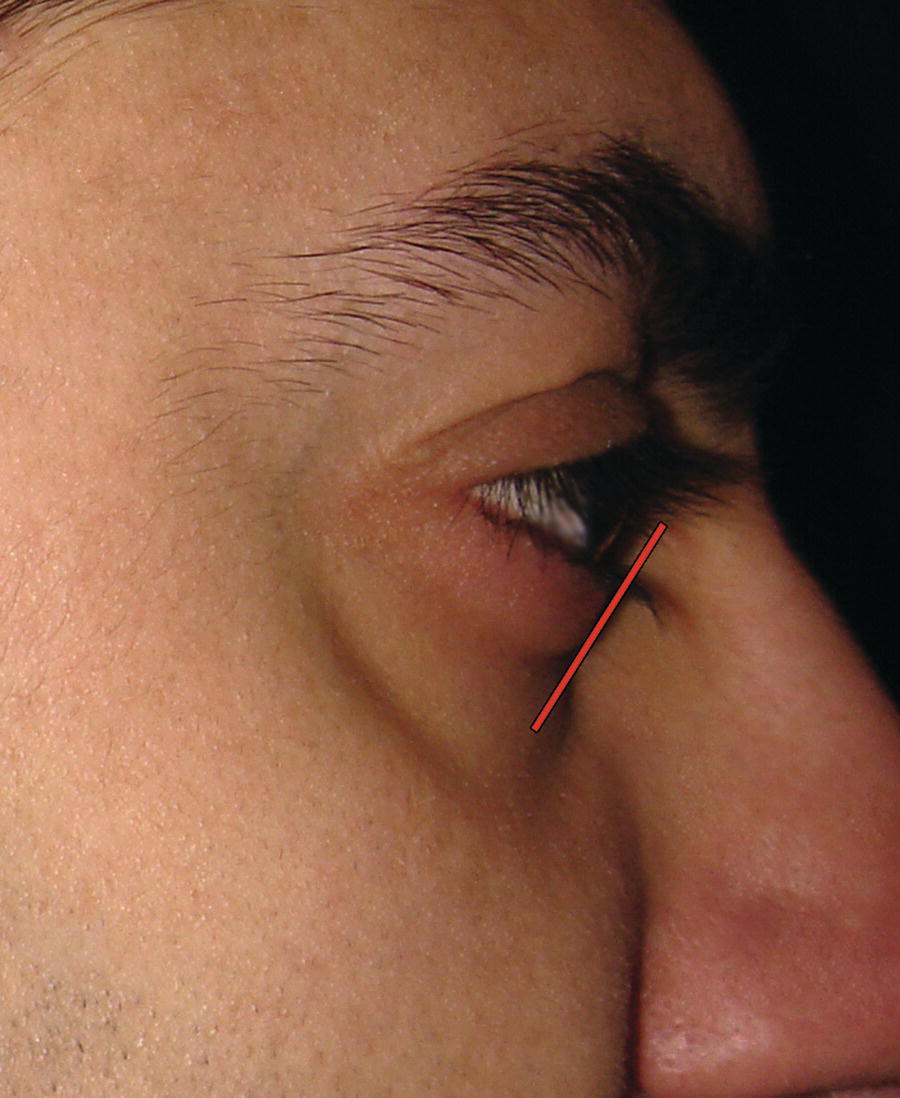

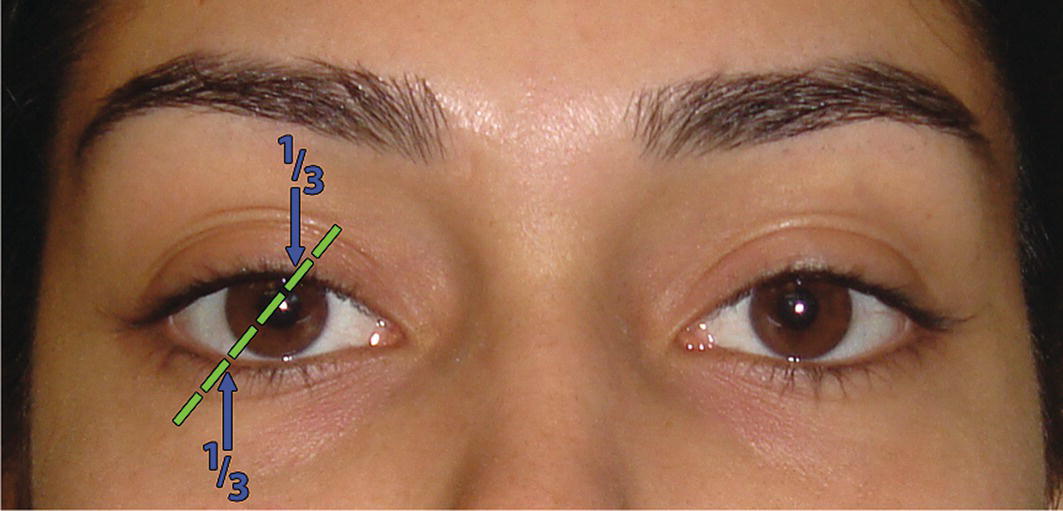

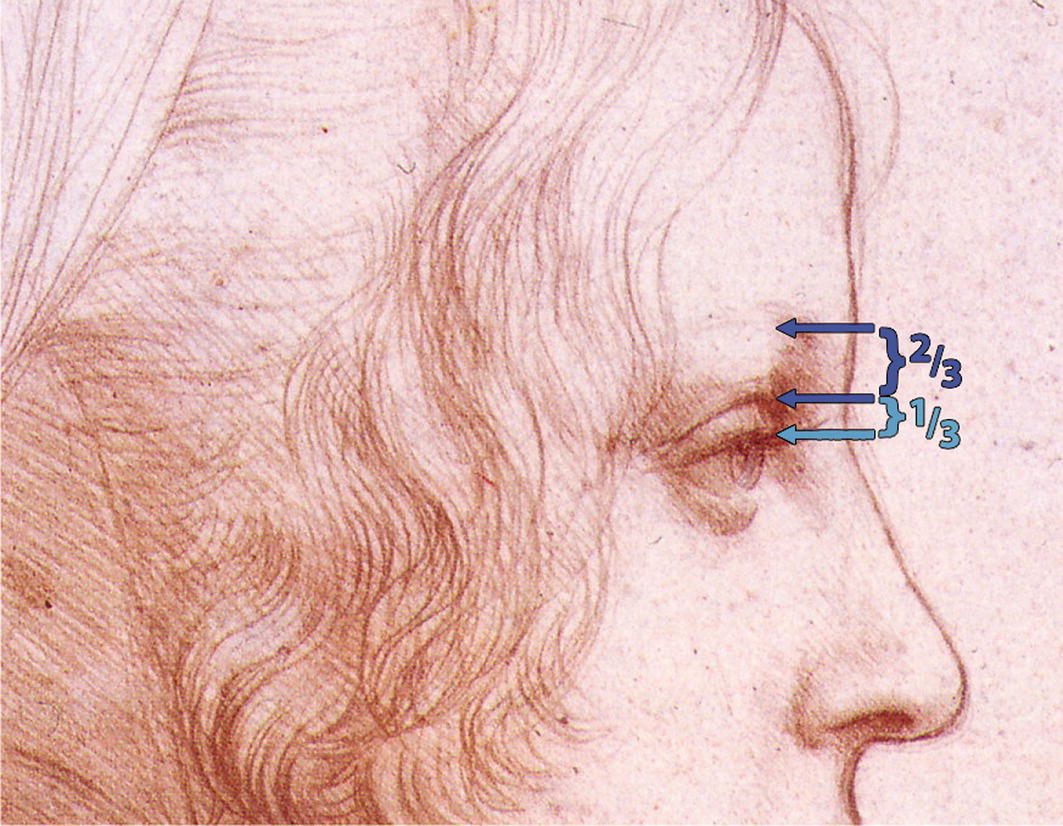

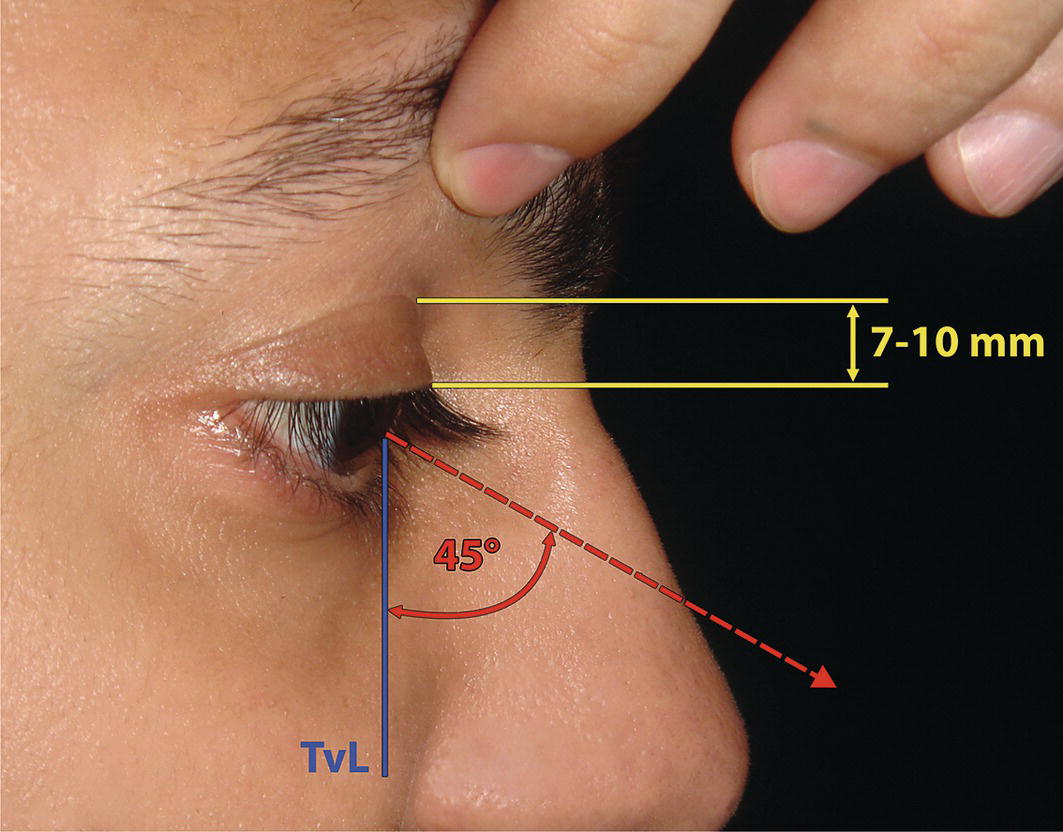

‘If I could write the beauty of your eyes And in fresh numbers number all your graces, The age to come would say, “This poet lies; Such heavenly touches ne’er touch’d earthly faces”.′ William Shakespeare, extract from Sonnet 171 The above extract from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 17 proves two things; firstly, the unsurpassed genius of William Shakespeare, and secondly, the importance of the eyes in facial aesthetics. Perhaps more has been written about the beauty of the eyes than any other facial feature. The orbital region, composed of the visible eye, eyelids and eyebrow, forms an important facial aesthetic unit, crucial to an attractive appearance and vital for communication through facial expression (Figure 12.1). The eyes convey thought. The Roman philosopher Cicero (106–43 bc) is quoted as saying, ‘The face is a picture of the mind as the eyes are its interpreter’.2 This formed the basis of the Latin proverb: ‘The face is the index of the mind’. The Bible says: ‘The light of the body is the eye’.3 The Roman scholar Pliny the Elder (c. ad 23–79) wrote: ‘The eyes are the window to the soul’,4 a phrase made famous by Leonardo da Vinci: ‘The eye, which is called the window of the soul, is the chief means whereby the understanding may most fully and abundantly appreciate the infinite works of nature’.5 The theologian and scholar Saint Jerome (ad 342–420) wrote: ‘The face is the mirror of the mind, and eyes without speaking confess the secrets of the heart’; this formed the basis of the French proverb: ‘The eyes are the mirror of the soul’.6 Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847) says: ‘The soul, fortunately, has an interpreter – often an unconscious but still a faithful interpreter – in the eye’.7 Figure 12.1 The eyes are arguably the most important facial aesthetic feature. (Detail, the angel from Madonna of the Rocks, Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1495–1508, National Gallery, London.) (Copyright © 2024 National Gallery, London. Reprinted by permission.) The eyes are also magnificently expressive. In his encyclopaedia entitled Historia Naturalis, Pliny the Elder wrote: ‘No other part of the body supplies more evidence of the state of mind’.4 The universality of the expressiveness of the eyes is also alluded to by the English poet George Herbert (1593–1633) who wrote: ‘The eyes have one language everywhere’.8 In Don Quixote, the Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes (1547–1616) supported this concept with the character Antonio’s amorous complaint: ‘The eyes those silent tongues of love’.9 When the Beagle docked in Peru, Charles Darwin described the women as shrouded in veils that only left one eye exposed, yet he felt this eye to be supremely expressive. ‘But then,’ he wrote, ‘that one eye is so black and brilliant and has such powers of motion and expression that its effect is very powerful.’10 ‘Her eyes like angels watch them still; Her brows like bended bows do stand …’ Thomas Campion (1567–1620), English poet and physician, Cherry‐Ripe11 The function of the eyebrows is to act as umbrellas for the eyes; Cicero explained that the eyebrows prevent forehead perspiration from falling into the eyes.2 Yet eyebrow shape and position has a profound influence on communication by way of facial expression. Simply raising or lowering the medial brow reflects a change in expression from surprise to anger (see Chapter 3). ‘The eyebrows form but a small part of the face, and yet they can darken the whole of life by the scorn they express,’ said the Athenian orator Demetrius (350–280 bc). The importance of the orbital and periorbital region, including the eyes, eyelids, eyelashes and eyebrows, cannot be underestimated in facial aesthetic analysis. The orbit is a bony cavity shaped like a pyramid tilted on to one side, with the apex at the back, and the base forming the opening on the front of the facial skeleton (Figure 12.2). This pyramid‐shaped orbital cavity contains the eye, which is the organ of vision, and various accessory ocular structures, including the extraocular muscles which move the eye, the eyelids, conjunctiva, part of the lacrimal gland, and orbital fat, which fills the spaces in the orbit, surrounding the optic nerve and stabilizing and cushioning the eye. Figure 12.2 Orbital anatomy: Figure 12.3 Eyelid anatomy: the tarsal plates, palpebral ligaments and orbital septum of the right eye: The eyelids (palpebrae) are two thin moveable folds, which cover the anterior surface of the eye (Figure 12.3). By their closure, they function to protect the eye from trauma or excessive light. The act of blinking, which occurs roughly 15 times per minute, maintains a thin film of tears over the cornea. The eyelids are covered in front with loose skin and behind with adherent conjunctiva, a transparent mucous membrane that covers the internal palpebral surfaces and is reflected over the sclera, where its epithelium becomes continuous with that of the cornea. Their skeletal framework is the orbital septum, thickened at the margins of the lids to form the superior and inferior tarsal plates, which are formed of dense fibrous tissue. The orbital septum has a separation between the two lids: the palpebral fissure. The medial and lateral palpebral ligaments anchor the tarsal plates to the anterior lacrimal crest and the marginal tubercle of the zygomatic bone, respectively. The medial commissure where the upper and lower lids meet is the medial canthus; laterally it is the lateral canthus. The skin overlying the eyelids is thin and densely adherent to the margins of the palpebral fissure; here, just outside the margin, are the eyelashes, short hairs whose follicles are stabilized by being attached to the rigid tarsal plates. The upper eyelashes curve upwards and the lower curve down so that upper and lower lashes do not intertwine when the lids are closed. Figure 12.4 The eyes and eyelids (surface features): The visible eye is about one‐sixth of the entire eyeball (or globe), and its special attraction is partly due to the characteristic arrangement of its three interacting components: the white sclera, the coloured iris and the black pupil (Figure 12.4). The white colour of the exposed sclera is important as it contrasts with the darker iris and pupil, highlighting eye movement, which is vital for communication. Surrounding the pupil is the iris, an adjustable diaphragm whose contraction and relaxation leads to pupillary constriction and dilatation, thereby controlling the amount of light entering the eye; pupillary diameter may vary from 1mm to at least 8 mm. Alteration in the diameter of the pupil also occurs as an emotional response. The layperson term ‘eye colour’ refers to iris pigmentation, which is genetically determined. The iris is named after the rainbow, though its range of colour extends only from light blue to very dark brown. The colour may vary between the two eyes and even within the same iris. The distribution of pigment is often irregular, producing a flecked appearance. Each iris pattern is unique, much like fingerprints, permitting iris recognition systems to identify individuals. The transparent convex anterior portion of the outer fibrous covering of the eyeball is termed the cornea, which covers the iris and pupil and is continuous with the sclera. The patient should be examined in natural head position, with the eyebrows and forehead in repose. The position of the eyebrow is vitally important in the evaluation of the periorbital region and is undertaken before evaluation of the eyelids. There is considerable individual variation in the position and contour of the eyebrows. The ‘ideal’ male eyebrow is positioned on or close to the supraorbital rim and is essentially horizontal, or mildly arced in orientation; whereas the female eyebrow is positioned above the supraorbital rim and is shaped as a gentle arc.12 The female lateral brow is positioned up to 10 mm superior to the supraorbital rim; the medial brow is usually 2 mm inferior to the lateral brow. The medial and central portions of the eyebrow are wider than the lateral portion. The medial brow starts approximately above the medial canthus. In women, the highest point or peak of the eyebrow arc should be level with the lateral canthus, but may be anywhere between the lateral limbus and lateral canthus of the eye (Figure 12.5). Leonardo da Vinci described a diagonal line, extending from the oral commissure (angle of the mouth), tangent to the ipsilateral lateral limbus; the extension of this line designates the peak of the eyebrow (Leonardo’s commissure‐limbus‐eyebrow peak line) (Figure 12.6). The medial curvature of the eyebrow continues with a smooth transition onto the aesthetic dorsal line of the nose; this curvilinear relationship is termed the brow‐nasal tip aesthetic line (Figure 12.7). In men, the brow‐nasal tip aesthetic line is more angular, in the form of an inverted ‘L’. Figure 12.5 Eyebrow aesthetics: The medial brow starts approximately above the medial canthus. In women, the peak of the eyebrow arc may be anywhere between the lateral limbus and lateral canthus of the eye. The lateral most part of the female eyebrow is on a line tangent to the lateral canthus from the nasal ala and approximately 2 mm superior to the medial most part of the eyebrow. Ptosis of the eyebrows may occur as a consequence of ageing or the inadvertent use of botulinum toxin type A. Ptosis of the medial eyebrow imparts an expression of anger, whereas ptosis of the lateral eyebrow conveys an expression of sadness. Ptosis of the entire eyebrow gives an aged and ‘exhausted’ appearance. In the normal Caucasian eye, the medial canthus is about 2 mm lower than the lateral canthus; this distance is increased in some East Asian ethnic groups. The inclination of the palpebral fissure is (Figure 12.8):13 An increase in this inferomedial orientation of the intercanthal axis (horizontal axis of the eye) is termed a ‘mongoloid’ slant; conversely, if the lateral canthus is inferior to the medial canthus, it is termed an ‘antimongoloid’ slant (Figure 12.9). However, it is better to avoid such terms and simply describe the orientation of the palpebral fissure and intercanthal axis, e.g. increased inferomedial slant or increased inferolateral slant. The left and right intercanthal axes should cross in the midline over the nasal dorsum; if they do not meet in the midline, this may be a sign of asymmetry. Figure 12.6 Leonardo’s commissure‐limbus‐eyebrow peak line. (Detail, Study of Proportions of the Face, Eyes and Eyebrows, Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1490, Biblioteca Reale, Turin.) Figure 12.7 Brow‐nasal tip aesthetic line. (Detail, Venus of Urbino, Titian, c. 1538, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.) Figure 12.8 Orientation of palpebral fissure: In the normal Caucasian eye, the medial canthus is about 2 mm lower than the lateral canthus, with a mild inferomedial orientation of the intercanthal axis (horizontal axis of the eye). Figure 12.9 Increased inferomedial slant and increased inferolateral slant of the intercanthal axis. Figure 12.10 The lower eyelid lies on an inferior‐posterior slope of approximately 45° from the upper lid in profile view. The eyelids cover the exposed anterior projection of the eyeball. The upper lid is larger, more curved and rather more active than the lower.14 The lower lid lies on a backward slope of approximately 45° from the upper lid in profile view (Figure 12.10). The superior most point of the curve of the upper lid margin is approximately one‐third of an eye width from the medial canthus. The inferior most point of the gently arcing lower lid margin lies between the pupil and lateral limbus, approximately one‐third of an eye width from the lateral canthus (Figure 12.11). Figure 12.11 The superior most point of the curve of the upper lid margin and the inferior most point of the gently arcing lower lid margin. The upper eyelid margin overlaps the superior iris limbus by 1–2 mm. There should be minimal or no scleral exposure between the lower lid margin and the inferior limbus; excessive scleral exposure below the iris is a sign of midfacial hypoplasia. The lower eyelid should be taut against the globe. The most common cause of post‐blepharoplasty lower lid ectropion is failure to recognize lower eyelid laxity prior to surgery. Two clinical tests are required to evaluate lower lid tone:15 The upper lid crease should be well defined and essentially parallel to the upper lid margin, and does not extend beyond the medial and lateral canthi. It normally divides the upper lid into an inferior tarsal portion (lower one‐third) and a superior septal portion (upper two‐thirds) (Figure 12.12). The upper lid crease may be absent in East Asian patients (Figure 12.13), and with ageing may become concealed behind redundant, ptotic skin (dermatochalasis). Lateral extension of the upper lid crease down over the eyelid and onto the lateral periorbital region is a sign of forehead ptosis, described as Connell’s sign. A useful guideline is to maintain a distance of approximately 15 mm between the eyebrow and the upper lid crease.16 The vertical position of the upper lid crease may be evaluated by Sheen’s test (lid margin to crease test) (Figure 12.14): the clinician elevates the eyebrow just enough to retract the excessive skin as the patient looks down at a 45° angle; the normal range of the distance from the central upper lid margin to the lid crease in white Caucasians should be 7–10 mm.17 Figure 12.12 The upper lid crease normally divides the upper lid into an inferior tarsal portion (lower one‐third) and a superior septal portion (upper two‐thirds). (Detail, Young Woman’s Head, Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1490, Royal Library, Windsor.) (With permission of The Royal Collection Trust/© His Majesty King Charles III 2024.) Figure 12.13 The upper lid crease may be absent in East Asian patients. The orbital fat pads lie deep to the orbital septum. Laxity of the septum may lead to bulging of the fat, termed prolapsed fat pads, often seen in ageing eyelids. Observation and gentle palpation should be undertaken with the patient supine in order to avoid retrusion of the fat into the orbital cavity. Absolute measurements of the eyes and interocular dimensions will vary depending on age, sex and ethnic background. Significant abnormalities in these dimensions may occur in congenital craniofacial abnormalities and certain syndromic conditions. Figure 12.14 Sheen’s test: the patient assumes a 45° downward gaze while the eyebrow is elevated just enough to retract the excessive skin. This manoeuvre should demonstrate the upper lid crease to be at least 7 mm from the central upper lid margin. TVL, true vertical line. Correction of such conditions requires complex craniofacial surgery, which may only be undertaken if deemed necessary to improve the patient’s quality of life. The following terminology may be employed (see Figure 9.26). An increased distance between the medial canthi of the eyelids; commonly found in Down syndrome.

Chapter 12

The Orbital Region

Introduction

The eyes

Eyebrows

Terminology

Anatomy

Clinical evaluation

Eyebrow position and contour

Orientation of palpebral fissure

Eyelids (palpebrae)

Eyelid shape

Eyelid tonicity

Upper lid crease (superior palpebral fold; supratarsal fold)

Orbital fat

Eye width and interocular dimensions

Telecanthus

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree