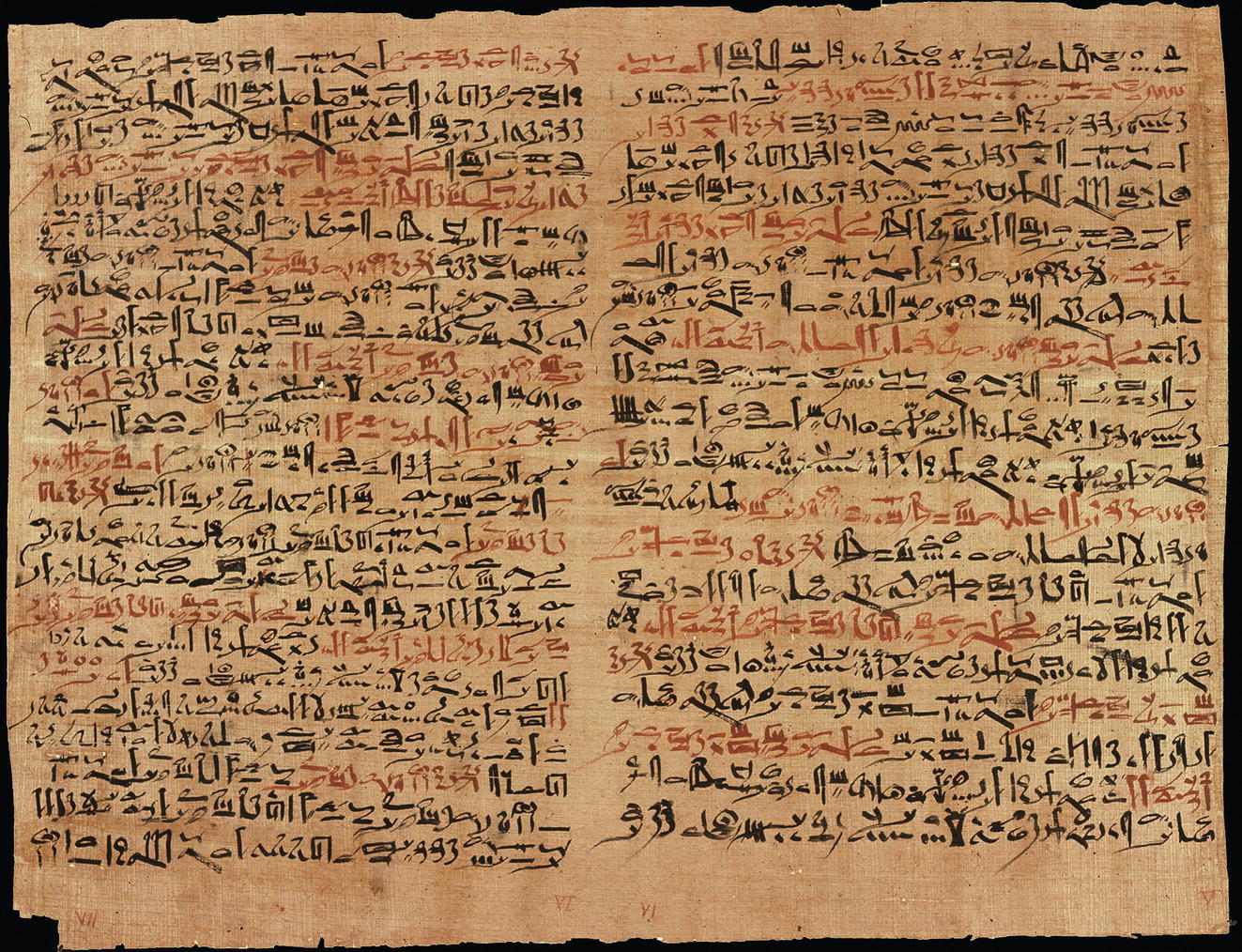

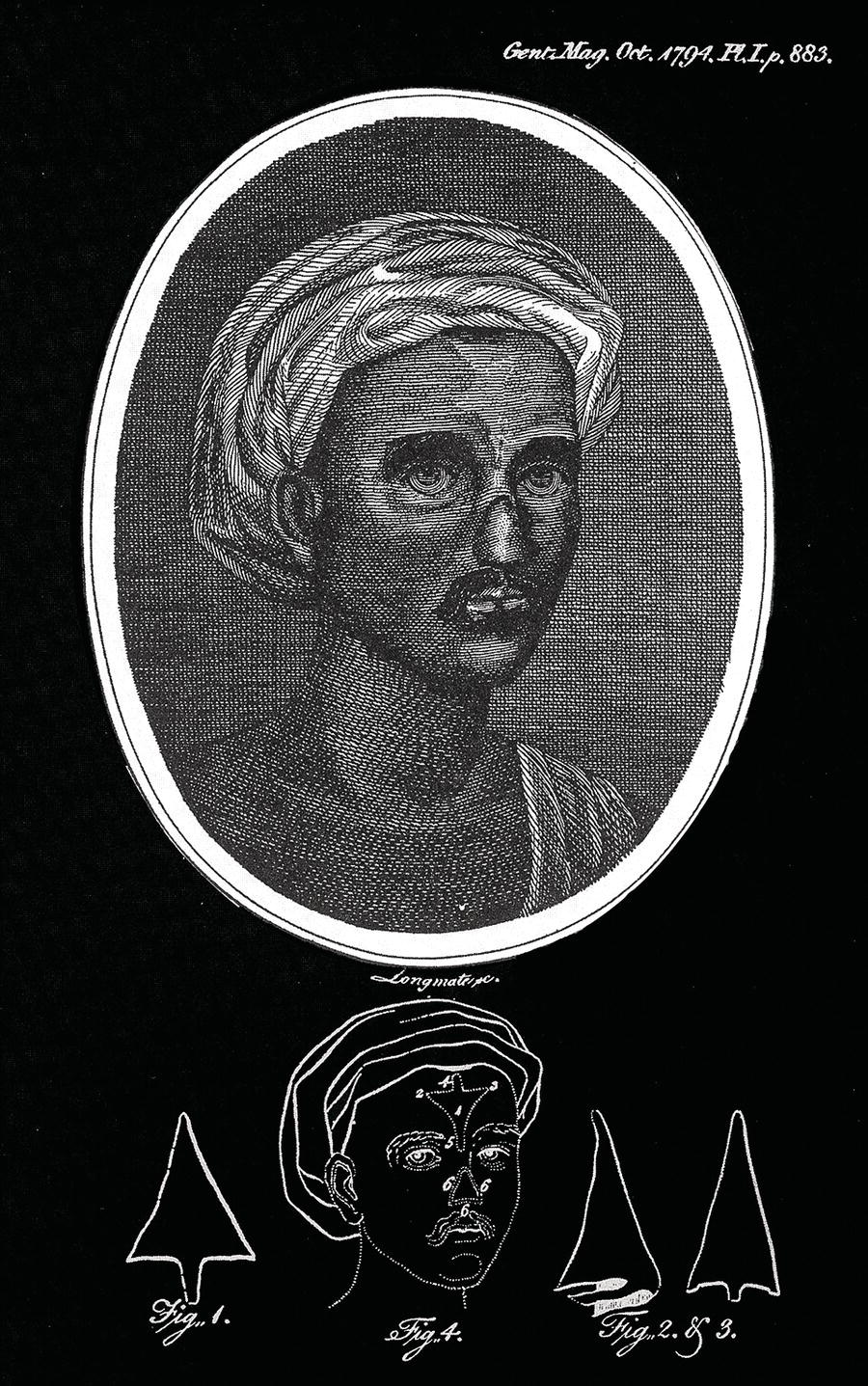

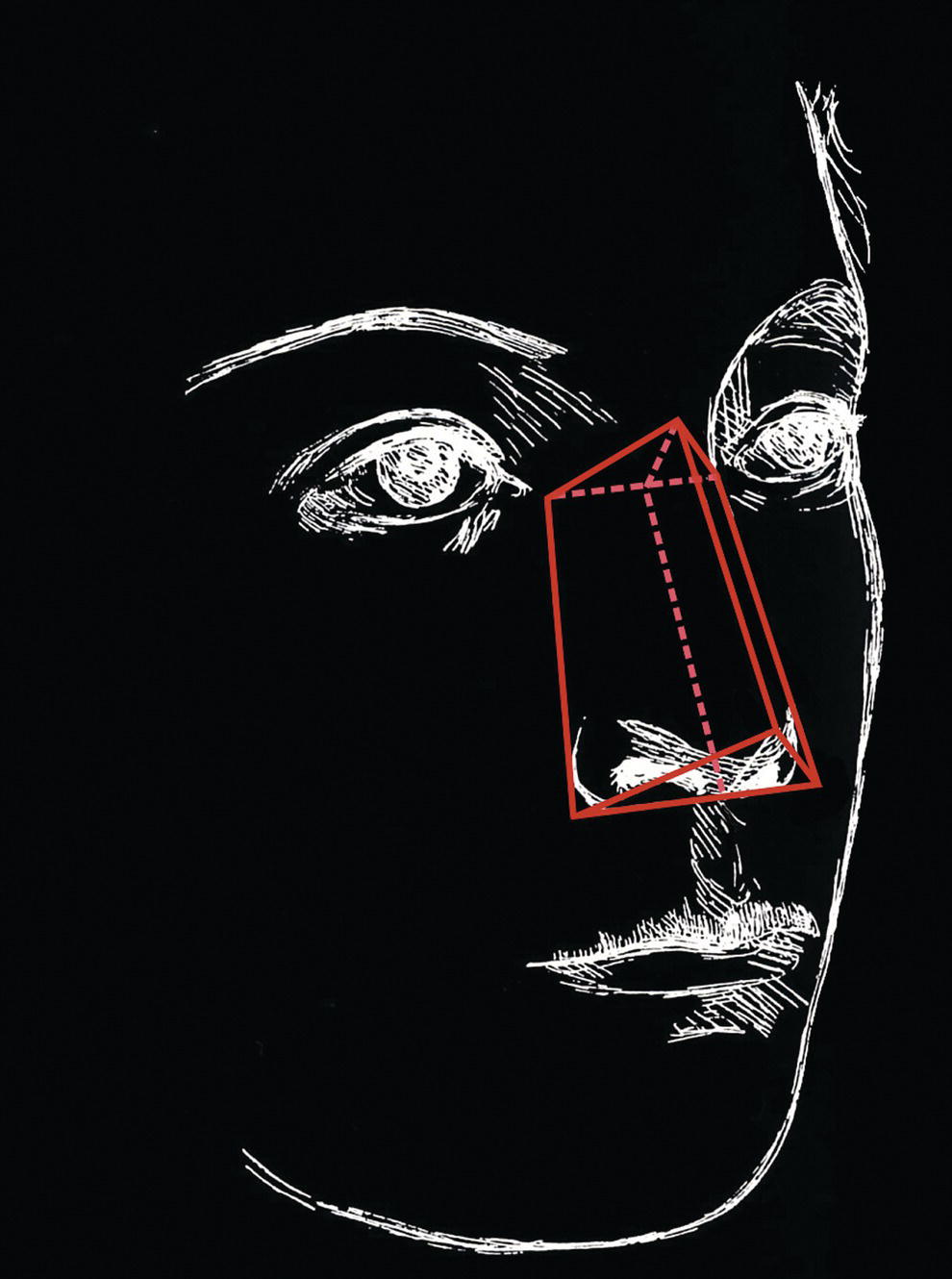

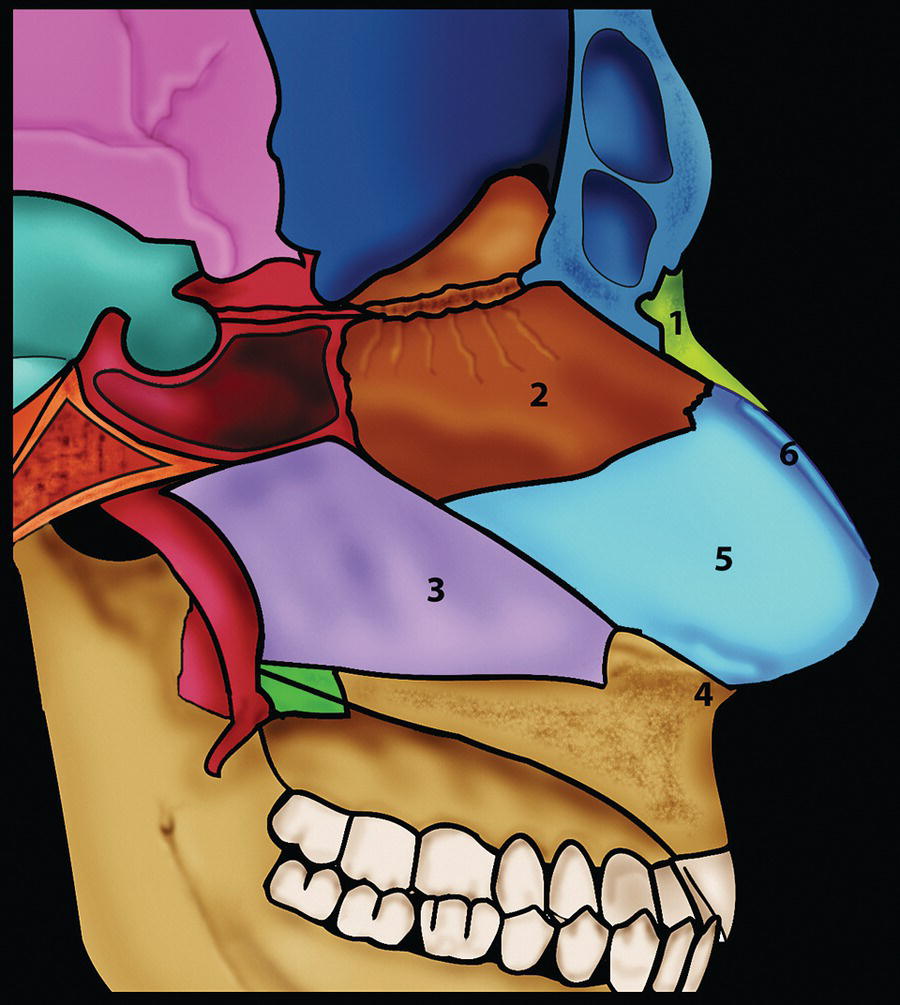

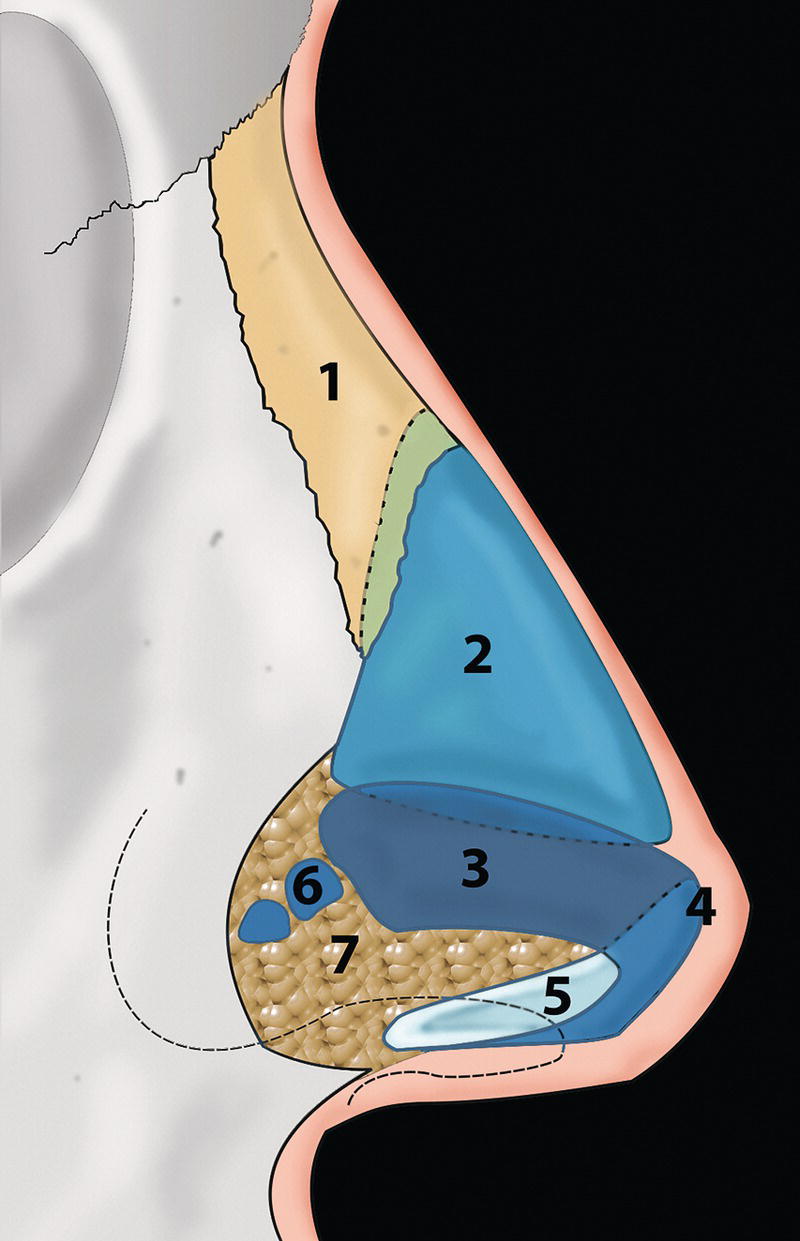

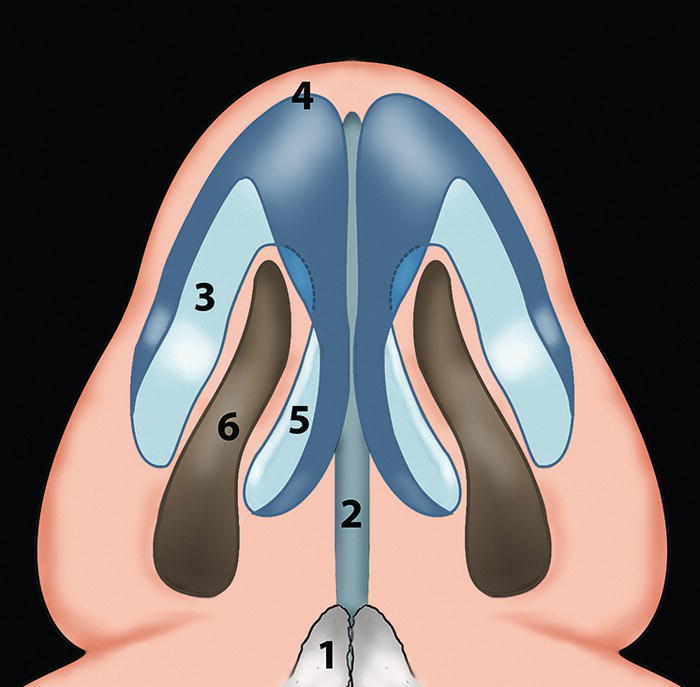

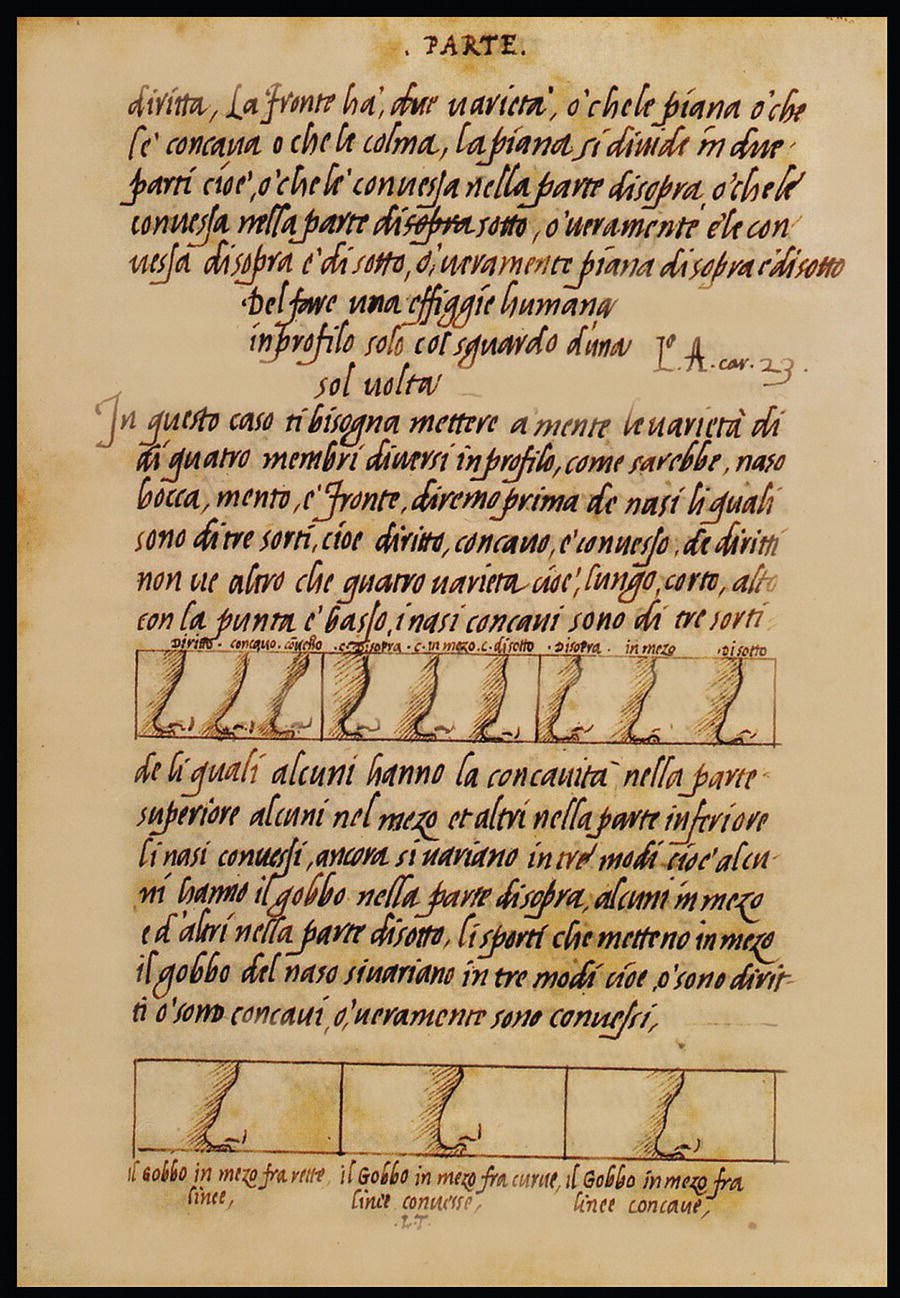

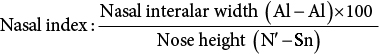

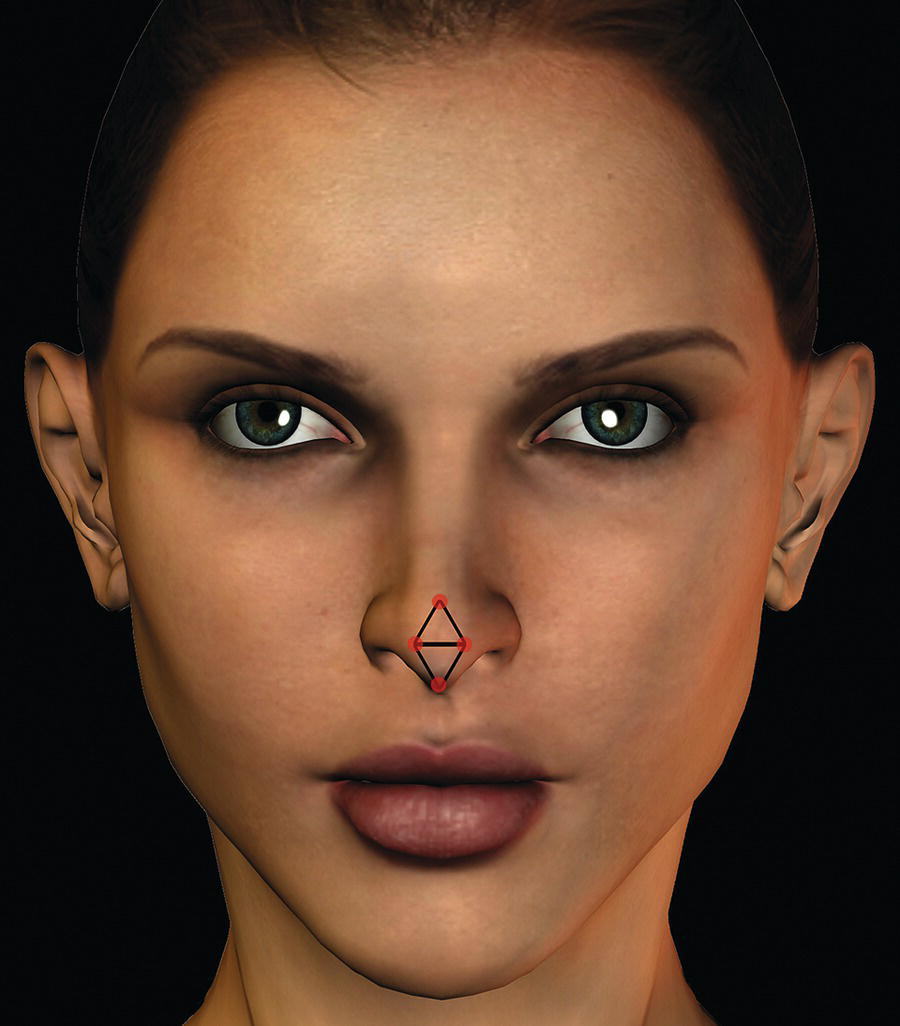

‘Cleopatra’s nose: had it been shorter, the whole face of the world would have changed’. Blaise Pascal (1623–62)Pensées (1670)1 The nose occupies the central position of the face and is the most prominent part of the facial profile. The nose thereby has a dominating effect on the facial profile, helping to establish the character of the midface. It has profound emotional, social, cultural and functional significance. The significance of nasal appearance has drawn the attention of writers throughout history. The most famous literary figure created by the playwright Edmond Rostand (1868–1918), Cyrano de Bergerac, was a character equally well‐known for his great skill in duels and for his inordinately long nose. Cyrano loves Roxane, yet is afraid to reveal his emotions, fearing her rejection due to his large nose. Cyrano says: ‘I pride myself in such an appendage, considering that a large nose is the proper sign of a friendly, good, courteous, witty, liberal, courageous man, such as I am,’ yet a moment later he bemoans his nose as a curse.2 As a result of its importance in facial appearance, nasal aesthetic and reconstructive surgery has a long history. The first written record of nasal trauma surgery dates back as far as 2700 bc to ancient Egypt and the physician Imhotep, as documented in the Edwin Smith Papyrus, a surgical treatise discovered in the nineteenth century by the American Egyptologist Edwin Smith (Figure 14.1).3 Smith recognized the importance of the document, buying it from a dealer in the city of Luxor in 1862. The surviving papyrus was probably written around 1700 bc but may be a copy of the originals written a thousand years earlier. The earliest concepts of reconstructive rhinoplasty emerged in northern India in the sixth century bc, attributed to the surgeon Susruta.4 Susruta (pronounced ‘Sushruta’) was a surgeon and teacher of the (classic) Ayurveda (Sanskrit: the ‘science/knowledge of life’) tradition of the ancient Indian system of surgery. The surgical treatise Susruta Samhita (‘Susruta’s Collection’), compiled in Vedic Sanskrit, is attributed to him. At the time amputation of the nose was one of the prescribed punishments for an act of dishonour, such as adultery. Susruta described reconstruction of the resulting defect using a cheek flap. Susruta is also credited with having originated the classical Indian method of nasal reconstruction, using a forehead flap pedicled near the root of the nose, though the technique does not appear in the Samhita. These works were lost for centuries, until Latin translations of the Persian physician Pur Sina’s (Avicenna) The Canon of Medicine introduced the ideas into Europe. In 1441, the Branca family of Sicily became familiar with the techniques of Susruta, reintroducing the Indian cheek flap technique of nasal reconstruction in Italy. In 1597, the Italian surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545–99) published a treatise entitled De Curtorum Chirurgia per Insitionem, which demonstrated the Italian method of nasal reconstruction using a pedicled flap from the arm (Figure 14.2).5,6 After Tagliacozzi’s death, his work was deemed immoral and suppressed by the influential religious elite. Two centuries later a landmark article was published in England, as a ‘Letter to the Editor’ in the Gentleman‘s Magazine (1794), describing Susruta’s ‘Indian method’ of nasal reconstruction using a pedicled forehead flap (Figure 14.3). This article, appearing under the initials ‘B.L.’, marked the reintroduction of reconstructive rhinoplasty into Europe. The operation, performed by an unknown Indian brick maker on the defect from a previously amputated nose of a bullock driver named Cowasjee, had been witnessed by two British surgeons in India. The English surgeon Joseph Constantine Carpue (1764–1846) subsequently spent 20 years in India studying local plastic surgical methods, performing the first major reconstructive rhinoplasty in England (1815), dealing with the nasal reconstruction in two British officers (published in 1816).7 The term rhinoplasty was coined by the German surgeon Carl Ferdinand von Graefe (1787–1840) as the title of his book (Rhinoplastik) published in 1818, describing both the ‘Indian’ and ‘Italian’ methods of nasal reconstruction. Figure 14.1 Plates 6 and 7 of the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, shown here discussing facial and nasal trauma. (New York Academy of Medicine.) Figure 14.2 The Italian surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545–99) published a treatise entitled De Curtorum Chirurgia per Insitionem, which demonstrated the ‘Italian method’ of nasal reconstruction using a pedicled flap from the arm. The history of elective aesthetic rhinoplasty is inextricably linked to that of reconstructive nasal surgery, the development of general anaesthesia and the possibility of aseptic procedures. Johann Friedrich Dieffenbach (1792–1847) succeeded von Graefe in Berlin, and provided a description of aesthetic rhinoplasty technique in his textbook (1845).8 Prior to 1887, rhinoplasty was a reconstructive procedure utilizing external incisions; the first aesthetic rhinoplasty undertaken by an intranasal approach is attributed to the American otorhinolaryngologist John Orlando Roe (1848–1915) from Rochester, New York. However, the pioneer of modern aesthetic rhinoplasty is acknowledged to be the Prussian‐born German Jakob Lewin (Jacques) Joseph (1865–1934), originally trained as an orthopaedic surgeon in Berlin (Figure 14.4). Joseph preferred the external approach to rhinoplasty, stressing the importance of direct visualization of the component parts. The publication of Joseph’s book (1931) is considered a landmark in aesthetic surgery.9 Two of Joseph’s pupils, the Polish American Joseph Safian (1886–1983) and Gustave Aufricht helped to publicize Joseph’s methods; Safian brought Joseph’s methods to New York and Aufricht later travelled to America gaining a reputation as a respected aesthetic surgeon.10 Figure 14.3 An article published in the Gentleman’s Magazine (1794), describing Susruta’s ‘Indian method’ of nasal reconstruction using a pedicled forehead flap marked the reintroduction of reconstructive rhinoplasty into Europe. The first publication of this illustration appeared a year earlier, in the Madras Gazette (1793). Refinements in rhinoplasty technique owe much to the modern pioneers of aesthetic rhinoplasty, such as Thomas D Rees, Jack H Sheen and M Eugene Tardy Jr, particularly the emphasis on maintaining and/or improving nasal function while conservatively creating results that appear ‘natural’ rather than ‘operated’. Figure 14.4 Jacques Joseph (1865–1934), considered to be the pioneer of modern aesthetic rhinoplasty. ‘Rhinoplasty seeks to cure psychological depression by restoring a normal shape to the nose. Its social importance is beyond question, and it represents a significant branch of surgical psychotherapy.’ Jacques Joseph (1865–1934)11 The nose consists of the external nose and the nasal cavity, which is divided into right and left halves by the midline nasal septum. The supporting framework of the external nose is bony in the upper third and cartilaginous in the middle and lower thirds. The external nose is ‘pyramidal’ in shape (Figure 14.5).9 Its cephalic most part, or root (radix nasi), is continuous with the forehead, and its free tip forms the apex. Inferiorly are the external nares (nostrils), two ellipsoidal apertures separated by the nasal septum and columella. The external nares are narrower anteriorly, measuring approximately 15–20 mm sagittally and 5–10 mm transversely. The lateral surfaces of the external nose unite in the median plane to form the ‘bridge’ of the nose or nasal dorsum (dorsum nasi), the shape of which exhibits great individual variability. The upper part of the external nose is kept patent by the nasal bones and the frontal processes of the maxillae. Below this the nasal cartilages form the walls of the external nose, supported in the midline by the cartilaginous part of the nasal septum. The lateral surfaces end below in the rounded alae nasi. Figure 14.5 The external nose is pyramidal in shape. (Redrawn from Joseph.9) The external nose is covered by skin that plays an important role in the final appearance of the nose after rhinoplasty. The skin is closely adherent to the underlying alar cartilages, but loosely attached and relatively mobile over the lateral (upper) cartilages and nasal bones. The skin is thicker over the tip (apex) and alae. The adherent skin over the nasal tip contains many sebaceous glands, which tend to progressively diminish in number superiorly. The skin extends into the vestibule immediately within the nostrils and here has a variable crop of stiff hairs; the mucocutaneous junction lies behind the hair‐bearing area. The osseous framework supporting the upper third of the external nose consists of the nasal bones, the frontal processes of the maxillae and the nasal processes of the frontal bones (Figure 14.6). Figure 14.6 The osseous framework supporting the upper third of the external nose. The cartilaginous framework of the external nose consists of the: Figure 14.7 The osseocartilaginous nasal septum (paramedian sagittal section). The septal cartilage is almost quadrilateral in shape in lateral view, hence the alternative term quadrangular cartilage. The acute angulation formed anteriorly at the transitional junction between the medial and lateral crurae creates a projection termed a dome; this is the highest point on the nasal tip. The two domes are separated by a notch palpable at the tip of the nose. Figure 14.8 The bones and cartilages of the external nose (lateral view). Figure 14.9 The bones and cartilages of the external nose (caudal view). The strut formed by the medial crura of the alar cartilages and the overlying skin that lies between the tip of the nose and subnasale is termed the columella. The columella is connected to the nasal septum posteriorly by the membranous septum, which is the caudal part of the nasal septum between the nares that is devoid of cartilage. The nose is arguably the most variable aesthetic unit of the face. Leonardo da Vinci (Figure 14.10) described a variety of nasal types in profile view, writing:14,15 Figure 14.10 Variations in nasal type in profile view. (Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1530–50; Biblioteca, Vatican City.) ‘Let us speak first of noses, of which there are three types, that is, straight, convex and concave. Of the straight type there are only four varieties, that is, long, short, high at the tip and low at the tip. Concave noses are of three types, of which some have the concavity on the upper portion, some in the middle, and others on the lower part. Convex noses again vary in three ways, that is, some have the projection on the upper portion, some in the middle and others in the lower part. The contours on either side of the projecting part of the nose vary in three ways, that is, they are straight, concave or extremely convex’. The nasal index reflects the width‐to‐height ratio of the nose (ratio of alar width to nasal height). It may be calculated by the formula: Farkas16 has provided values for North American Caucasians: A broad nose (nose wide for its height) has a high index value; a narrow nose (nose narrow for its height) has a low index value. In general, nasal morphology correlates relatively well with ethnic background, though considerable individual variability remains. Diagnosing clinicians should respect such ethnic nasal variation, striving to improve and refine the nasal appearance while maintaining ethnic features. There are three broad categories of nasal appearance commensurate with ethnic background (Table 14.1):17 Figure 14.11 Nasal index. Descriptive terminology regarding the spatial relationships of the nose relative to the rest of the craniofacial complex is important, permitting clear description of nasal morphology for diagnosis and treatment planning. The main axis of the nose stands at an angle to that of the face.18Craniofacial spatial relationships are described as superior, inferior, anterior and posterior. Nasal spatial relationships may be described as ‘cephalic’/‘cranial’, ‘caudal’, ‘dorsal’ and ‘basal’. Figure 14.12 Ethnic variations in nasal type. Table 14.1 Classification of nasal type according to nasal index Values according to Lang et al.17 Figure 14.13 Descriptive terms for relative nasal spatial relationships. (After Austermann.18) The framework of the nasal dorsum (‘dorsum nasi’ or ‘nasal bridge’) consists of the bony dorsum and cartilaginous dorsum. The rhinion (osseocartilaginous junction) is located at the junction of the nasal bones and upper lateral nasal cartilages; this region is termed the keystone area because of its key importance in stabilizing the nasal dorsum (Figure 14.14). The vertical distance from nasion (N′) to subnasale (Sn). The vertical distance from nasion (N’) to the nasal tip (pronasale, Prn). Figure 14.14 The nasal framework. The rhinion (Rh) marks the osseocartilaginous nasal junction. Figure 14.15 Nasal height, length and projection. The horizontal distance from the alar‐facial crease to the nasal tip. The projection of the nose from the face may also be measured from subnasale (sometimes termed ‘nasal depth’). Figure 14.16 Nasal aesthetic subunits. The external nose represents a facial aesthetic unit located in the centre of the face and comprised of a number of aesthetic subunits (Figure 14.16):12 The lobule itself may be considered as a number of adjoining subunits: Systematic and thorough clinical inspection and palpation is the cornerstone of aesthetic nasal evaluation. It is important to analyse the nose as an independent facial unit, and also to evaluate its size, morphology and position relative to its neighbouring facial structures and the entire craniofacial complex. The patient is examined in natural head position (NHP) with the teeth lightly in occlusion and the facial soft tissues in repose. Midface height (glabella to subnasale) should be approximately equal to lower anterior face height. Nasal height (nasion to subnasale) is approximately 45% of lower anterior face height. Mild nasal asymmetry is very common, but may often not be noticed by patients preoperatively. Patients tend to scrutinize their facial appearance far more following surgery; pre‐existing nasal asymmetries, if not fully discussed with the patient preoperatively or not fully corrected with surgery, may become anathema to the patient following surgery. Figure 14.17 Brow‐nasal tip aesthetic line. (Detail, Birth of Venus, c. 1485, Sandro Botticelli, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.) Sheen13 described the nasal tip as the nasal surface area contained within four tip‐defining points, the left and right domal defining points, supratip breakpoint and columellar breakpoint. Connection of these four landmarks should create two equilateral triangles (Figure 14.19). Figure 14.18 The normal angle of divergence of the domes has been described as between 35° and 60°. Excessive distance between the domal tip‐defining points may result in tip bifidity. The distance between the domal tip‐defining points is an important factor in nasal tip aesthetics, and relates to the divergence of the transitional segment that joins the medial and lateral crura. Figure 14.19 Sheen13 described the nasal tip as the nasal surface area contained within four tip‐defining points, the left and right domal defining points, supratip breakpoint and columellar breakpoint. Connection of these four landmarks should create two equilateral triangles. The columella is observed to hang just inferior to the inferior alar rims, giving the infratip lobule and alae a gentle ‘gull in flight’ appearance on frontal view, the columella being the gull’s body and the alar rims being the wings (Figure 14.20).

Chapter 14

The Nose

Introduction

Terminology

Anatomy

Soft tissue features of external nose

Skin of the external nose

Bony skeleton of the external nose

Cartilaginous skeleton of the external nose

Nasal type, topography and the subunit principle

Classification of nasal type

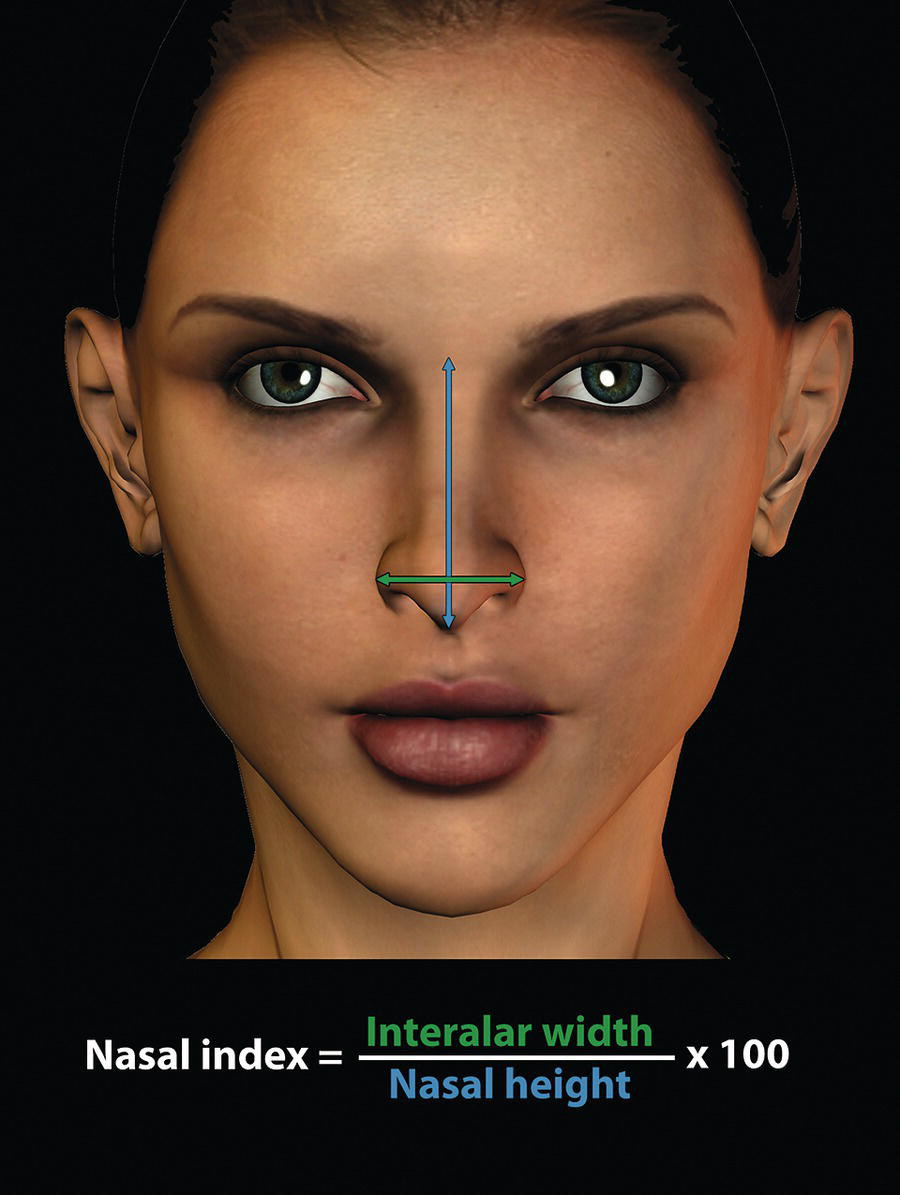

Nasal index (Figure 14.11)

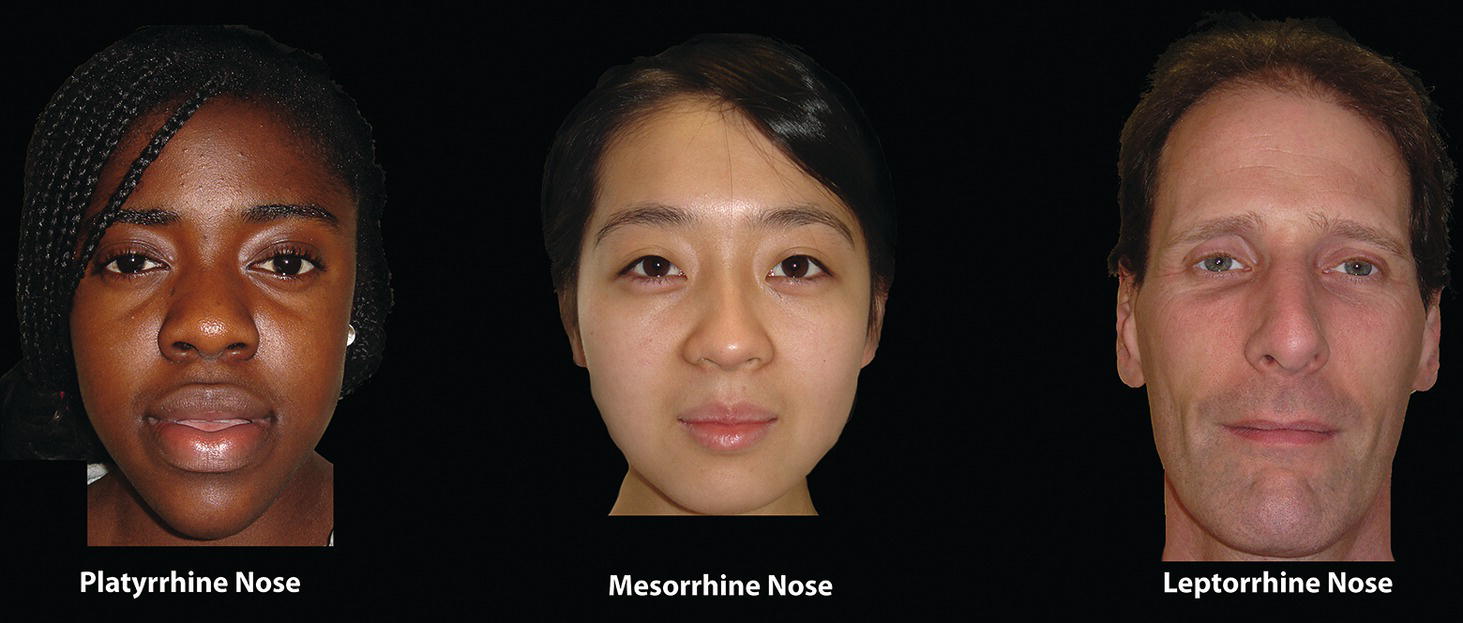

Ethnic variation (Figure 14.12)

Topographic nasal landmarks and nomenclature

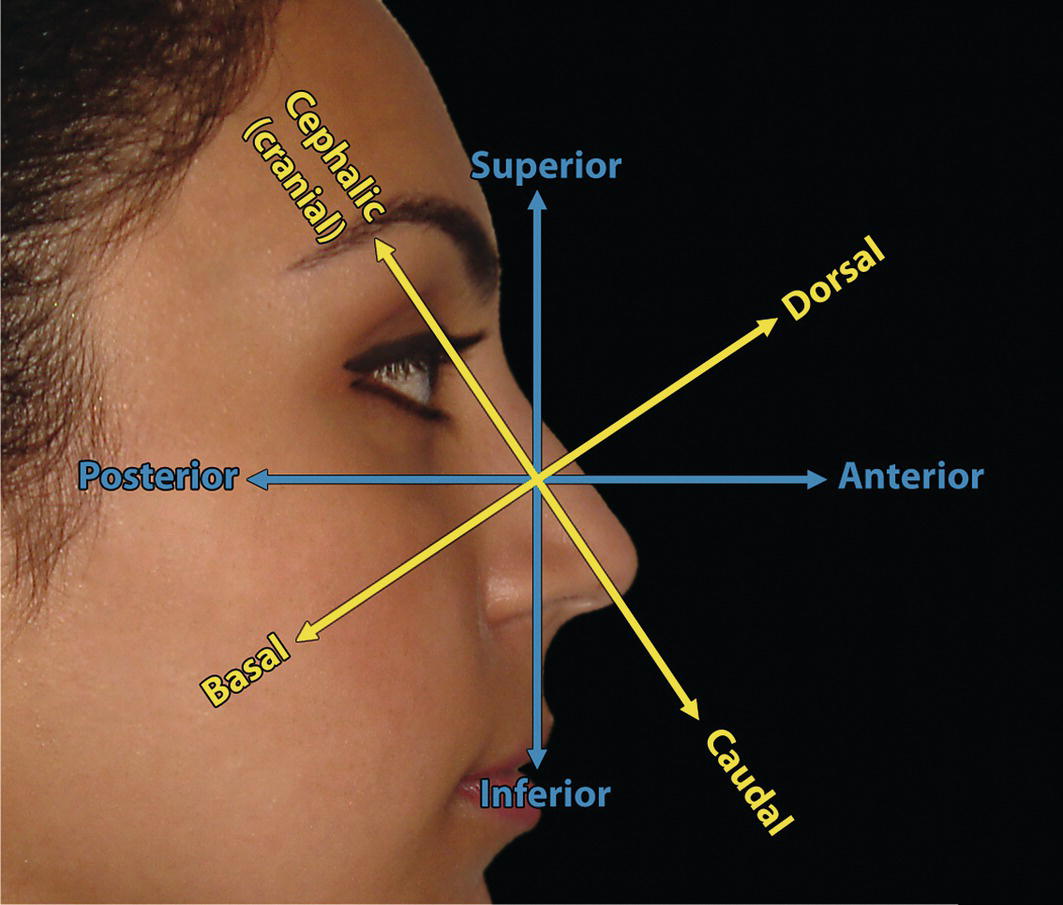

Relative nasal spatial relationships (Figure 14.13)

Nasal type

Nasal index

Hyperleptorrhine (excessively tall and narrow)

≤54.9

Leptorrhine (tall and narrow)

55.0–69.9

Mesorrhine (medium)

70.0–84.9

Platyrrhine (broad and flat)

85.0–99.9

Hyperplatyrrhine (excessively broad and flat)

≥100.0

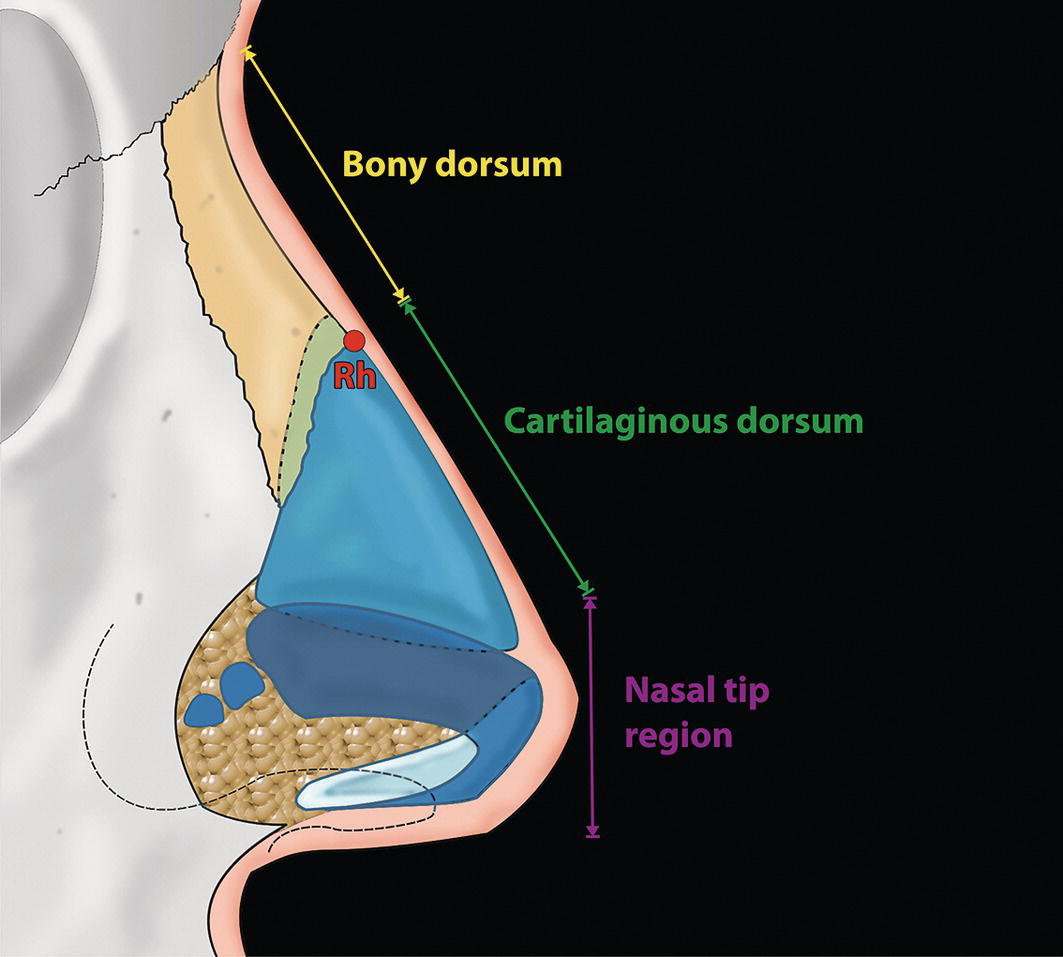

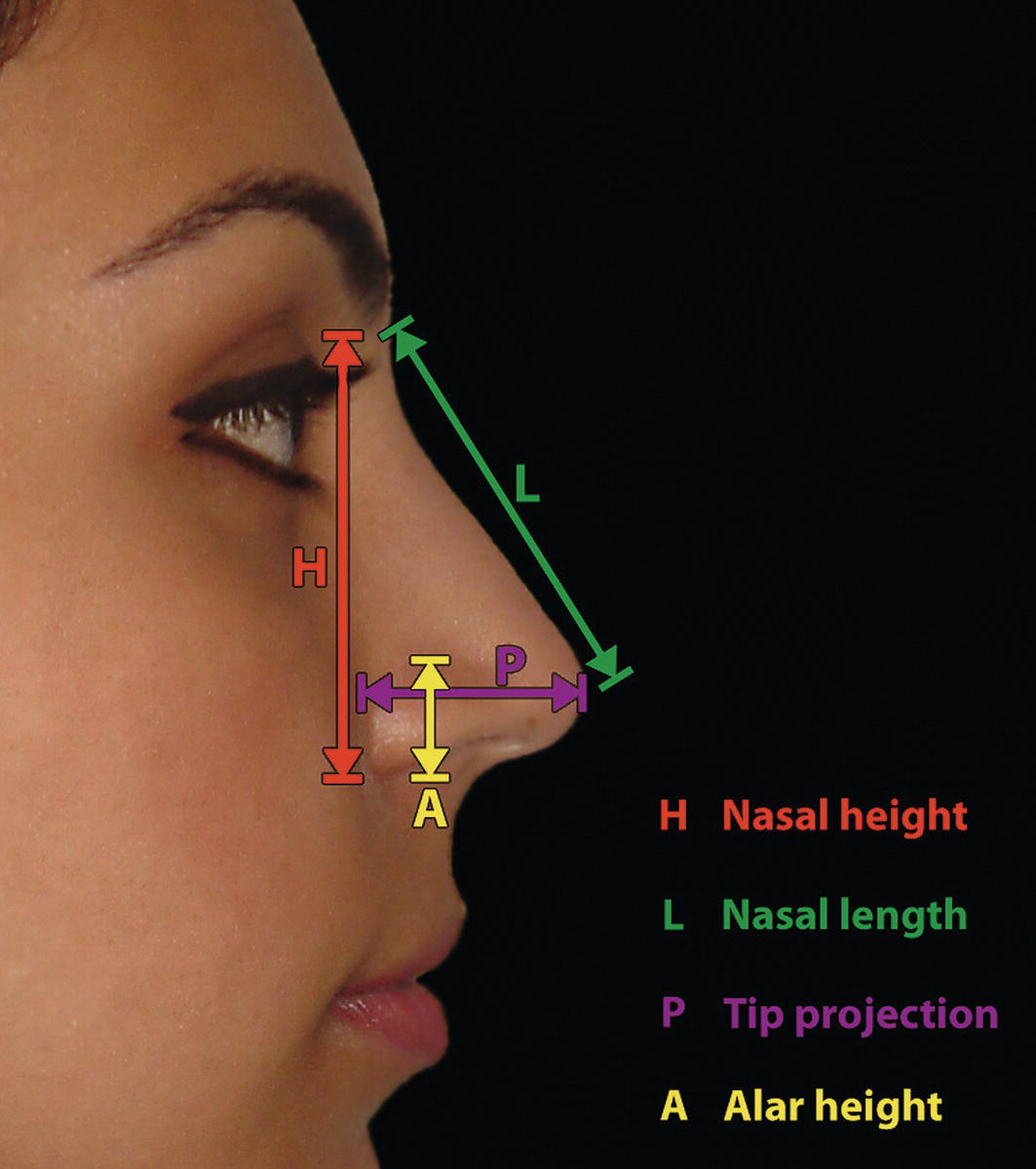

Nasal height (Figure 14.15)

Nasal length

Nasal tip projection

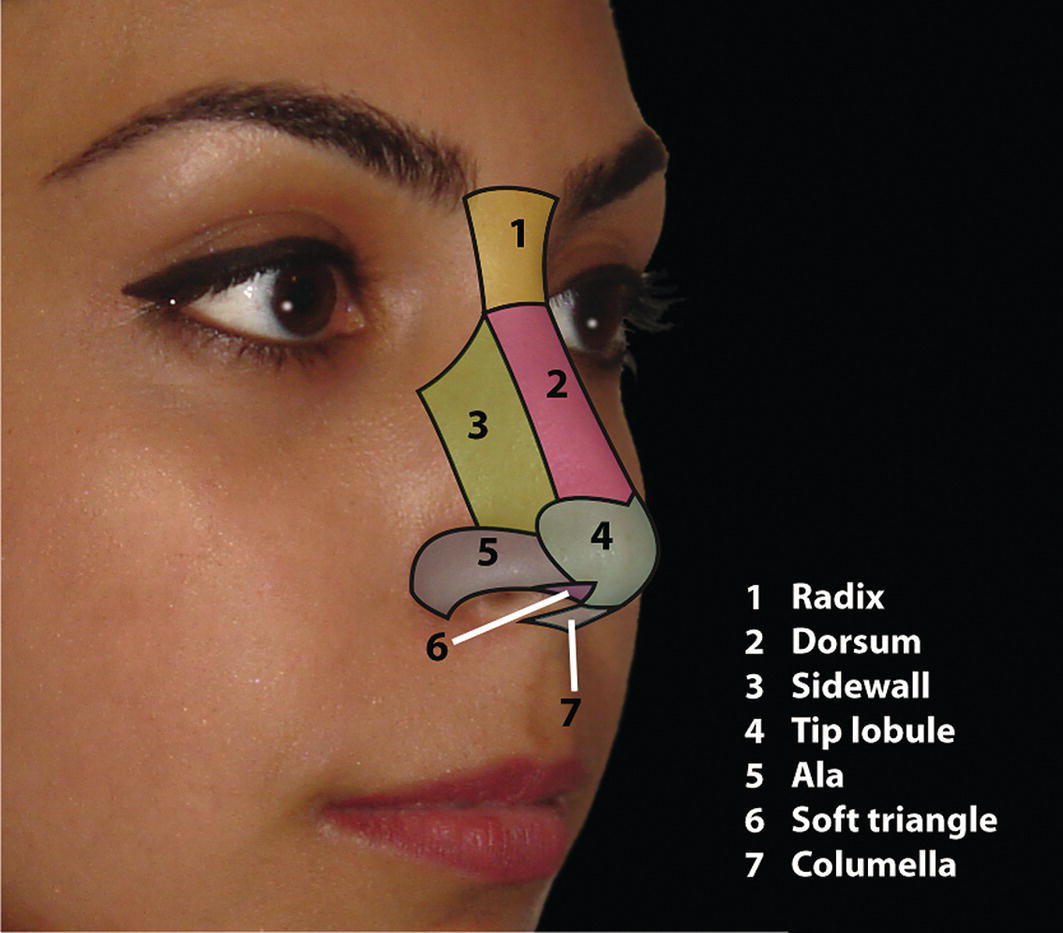

Nasal aesthetic subunits

Clinical evaluation

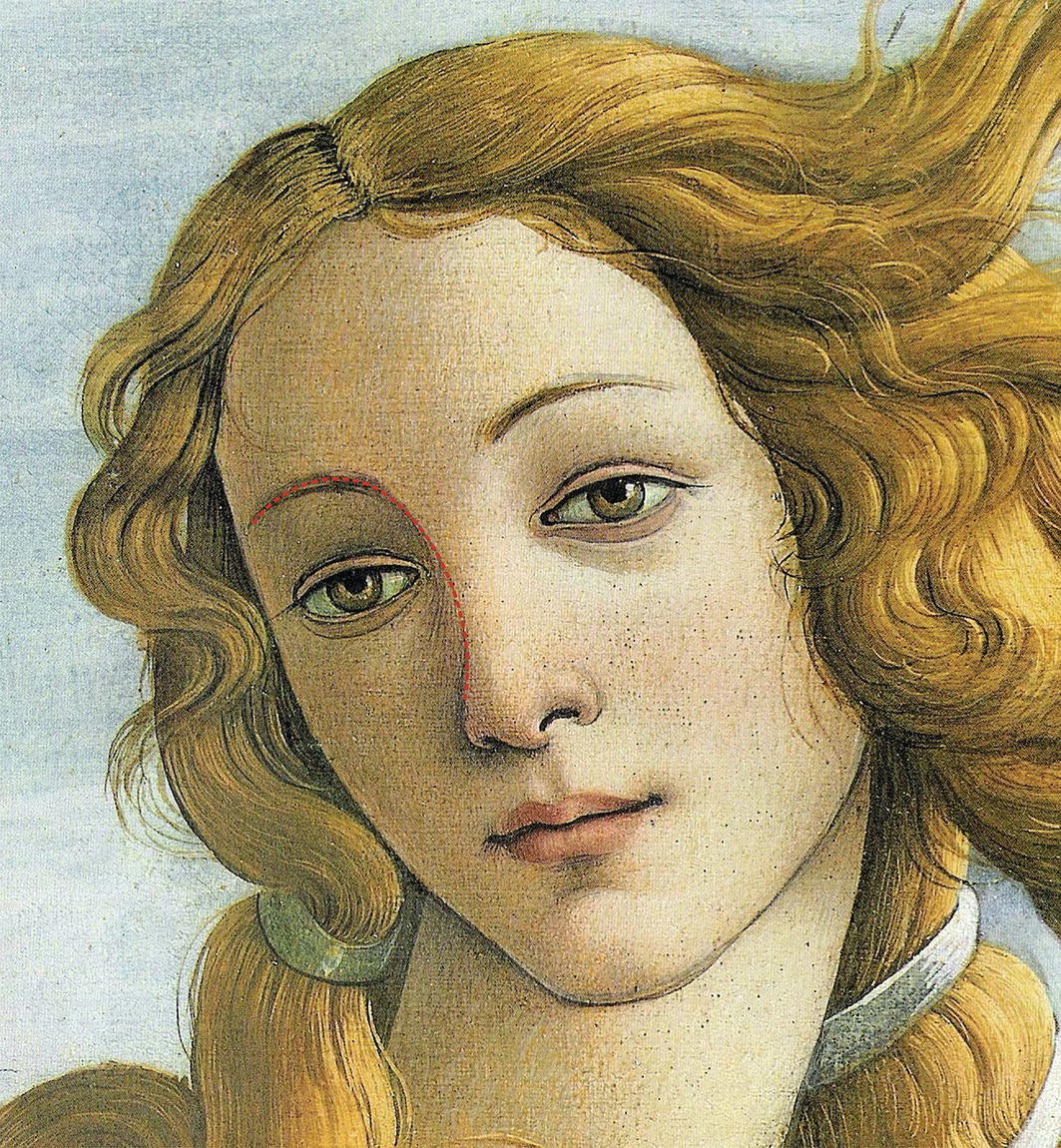

Frontal evaluation

Vertical proportions

Transverse proportions

Nasal symmetry and asymmetry

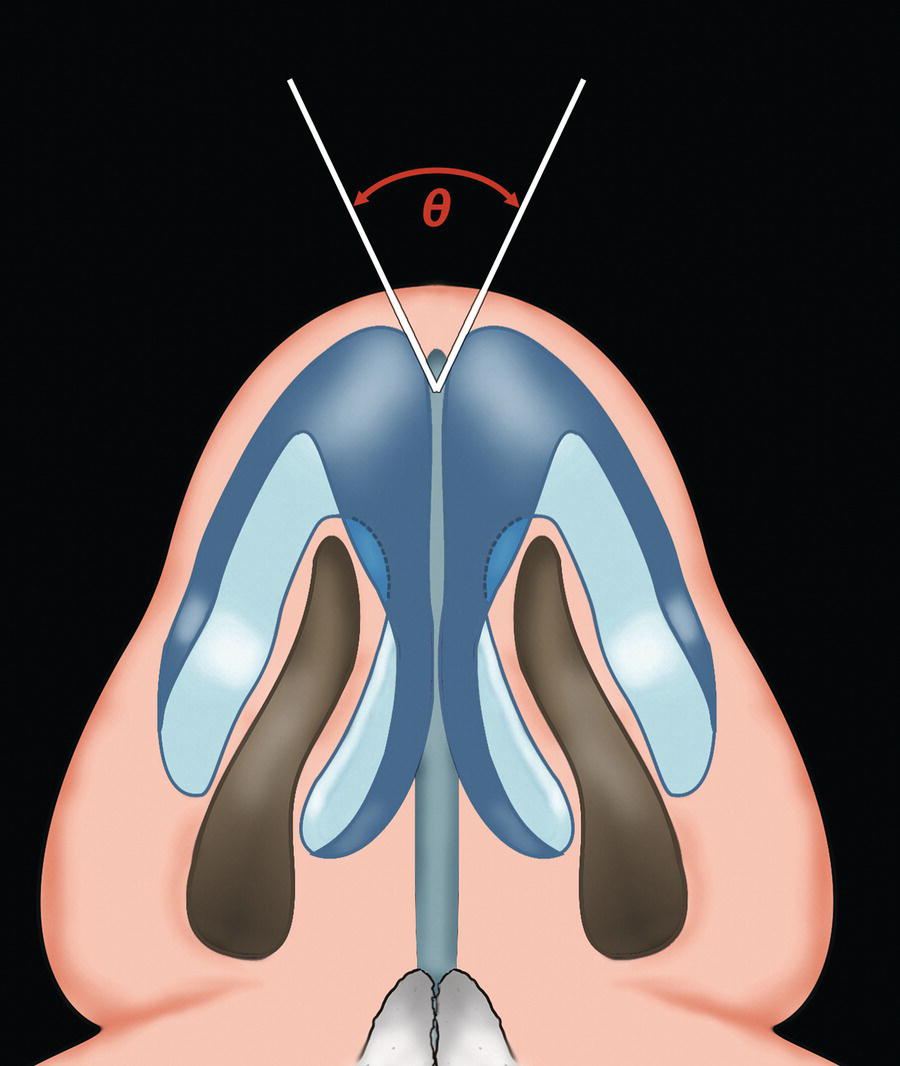

Nasal tip morphology

Columella–alar relationship (frontal view)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree