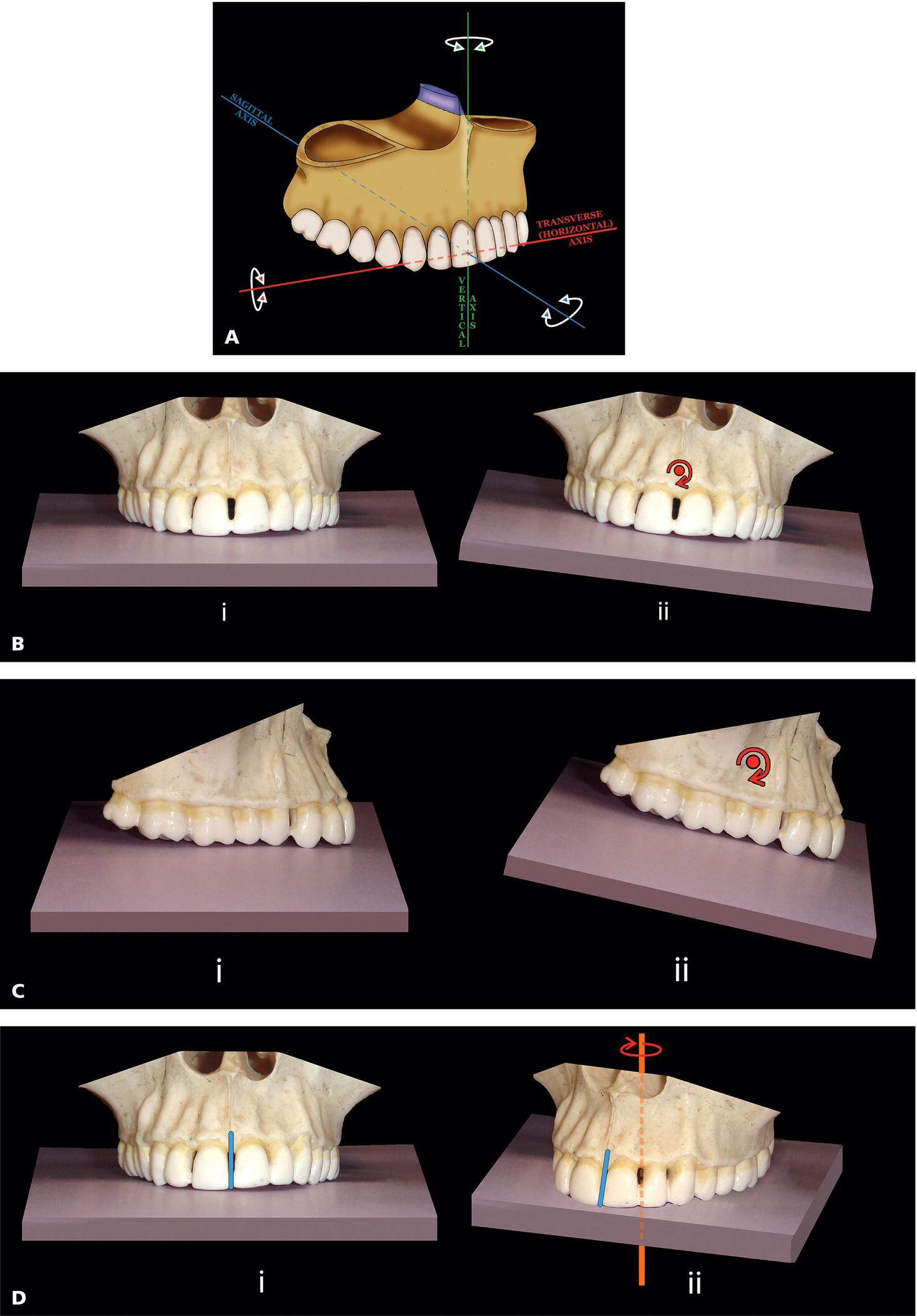

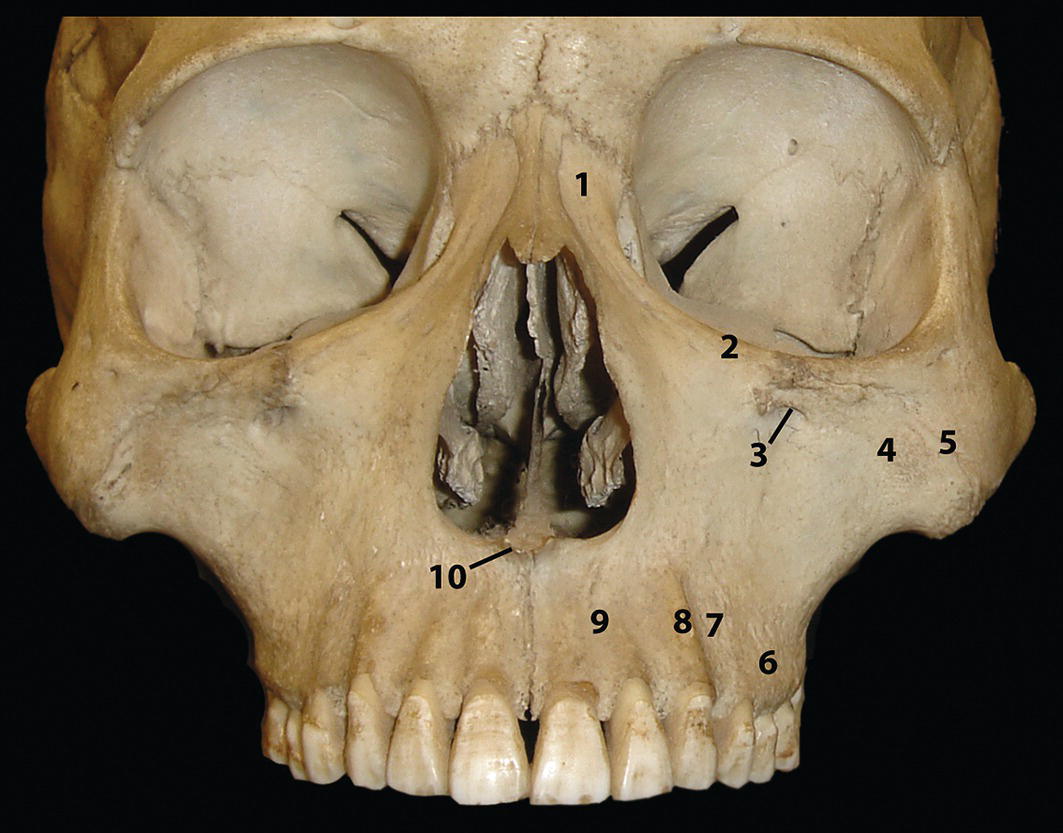

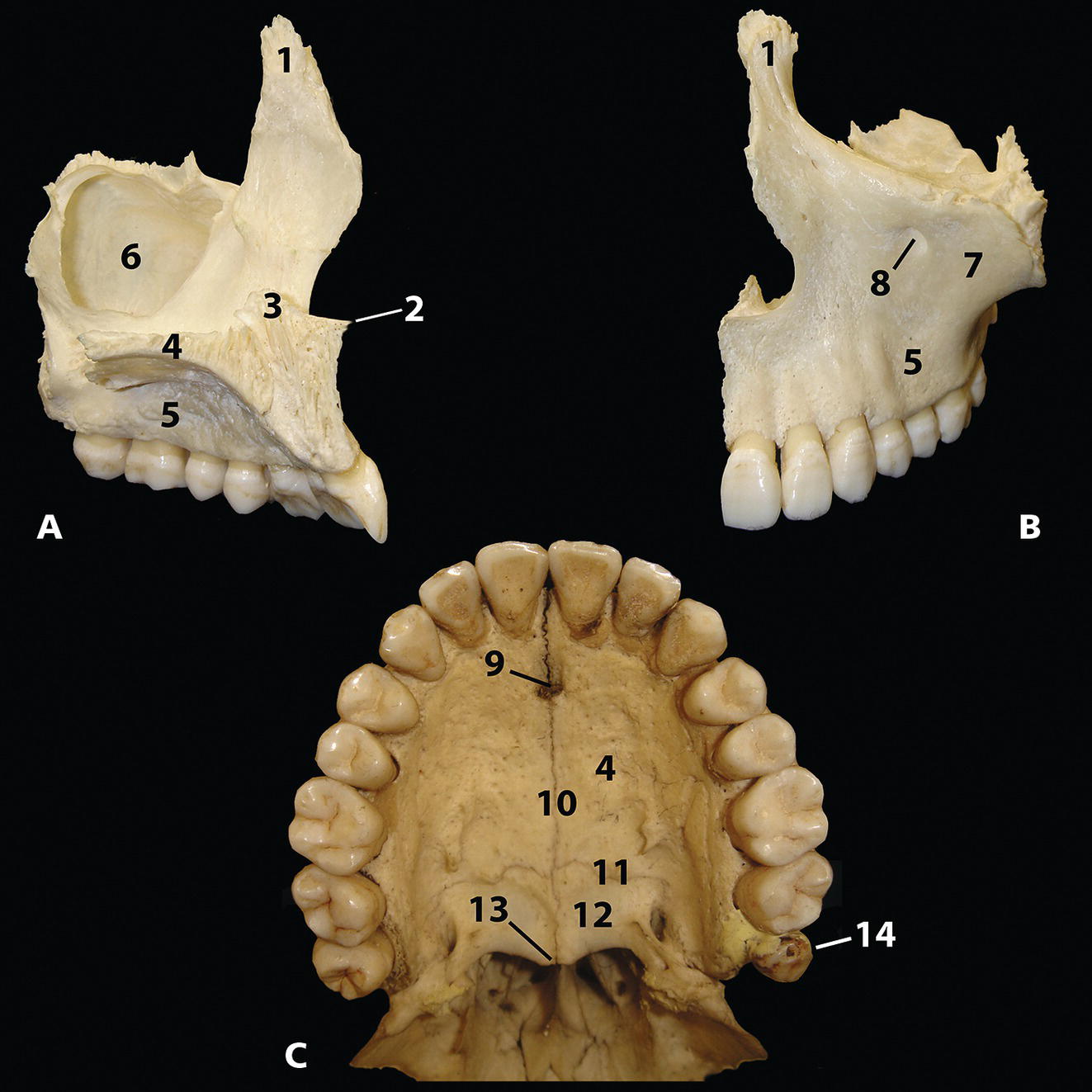

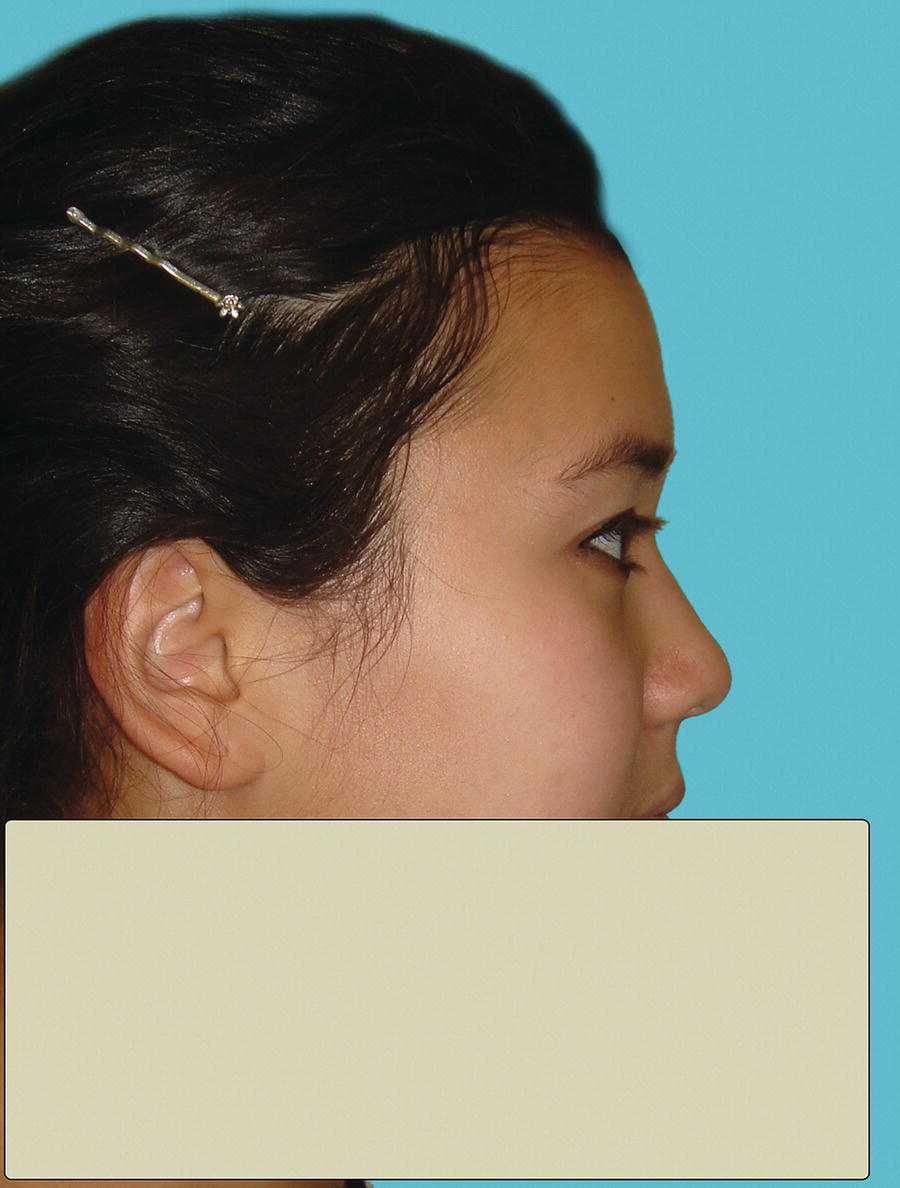

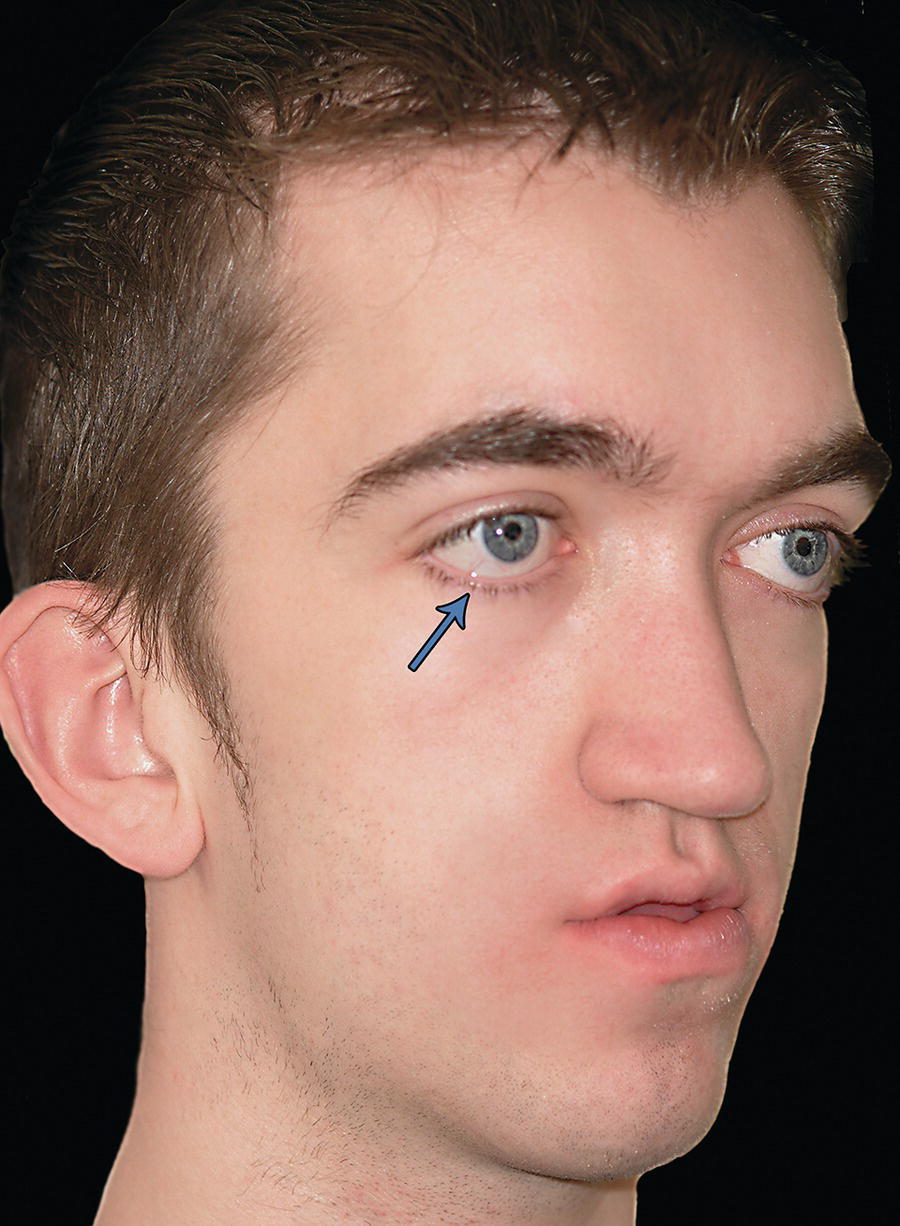

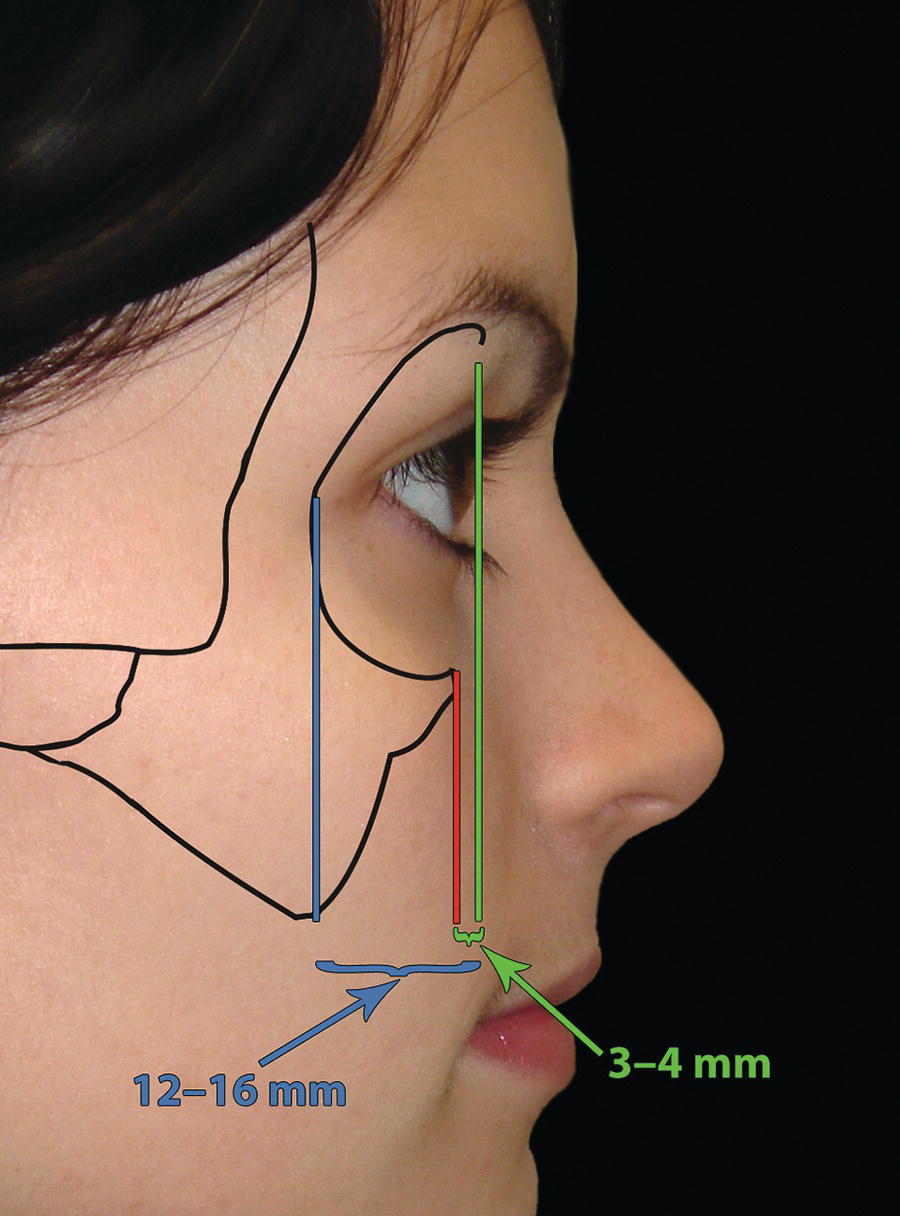

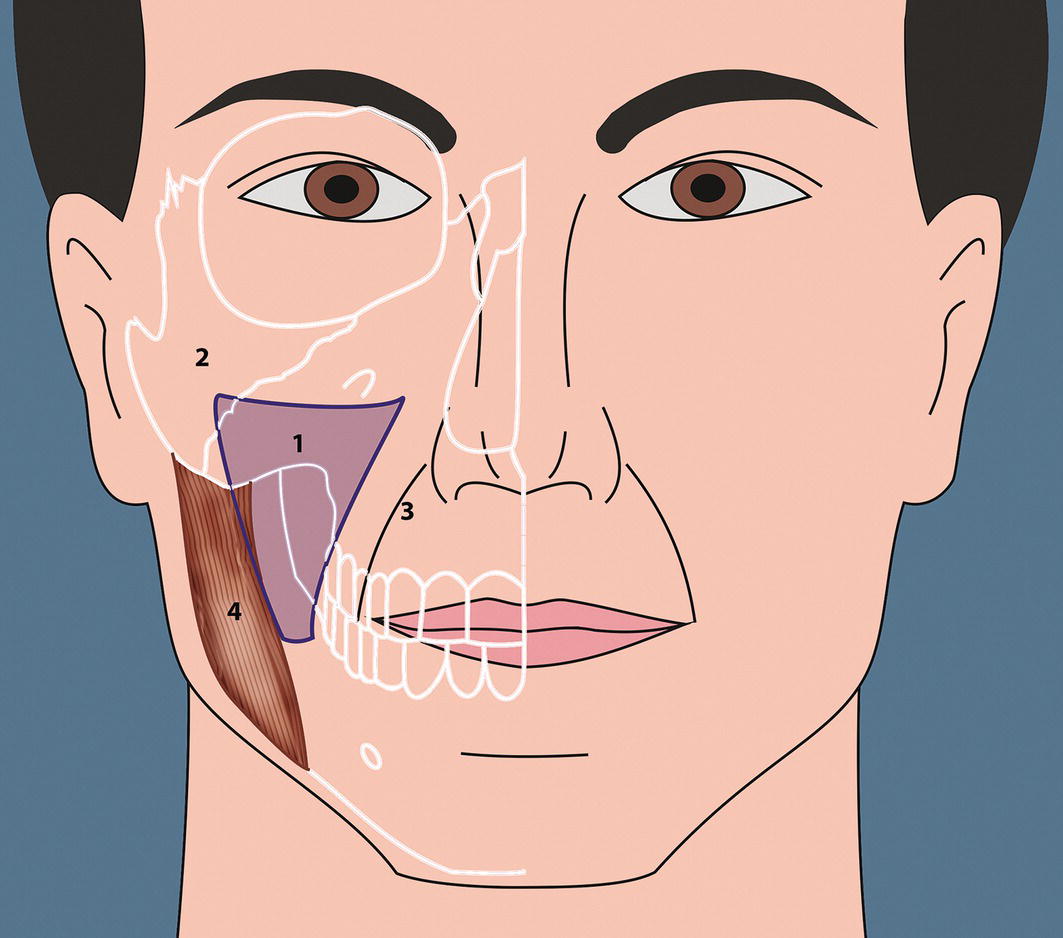

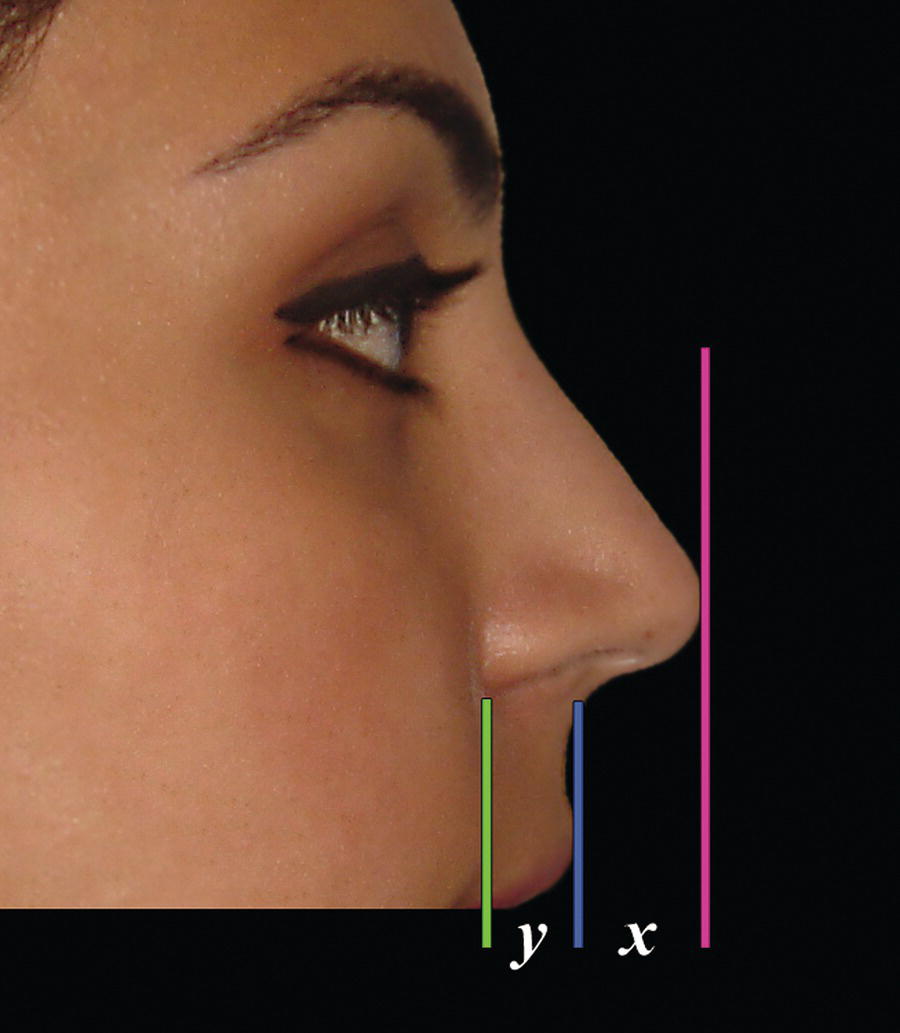

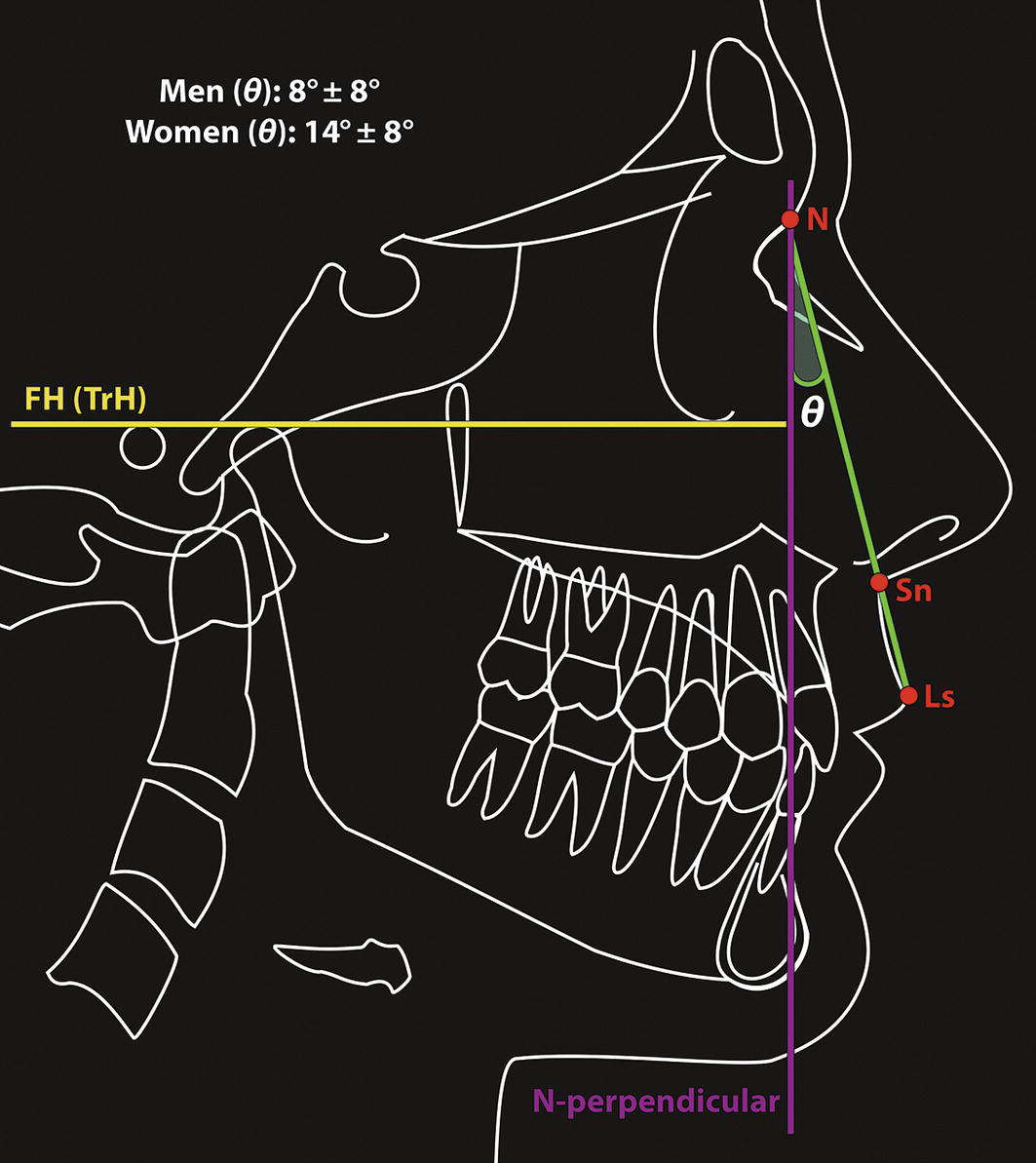

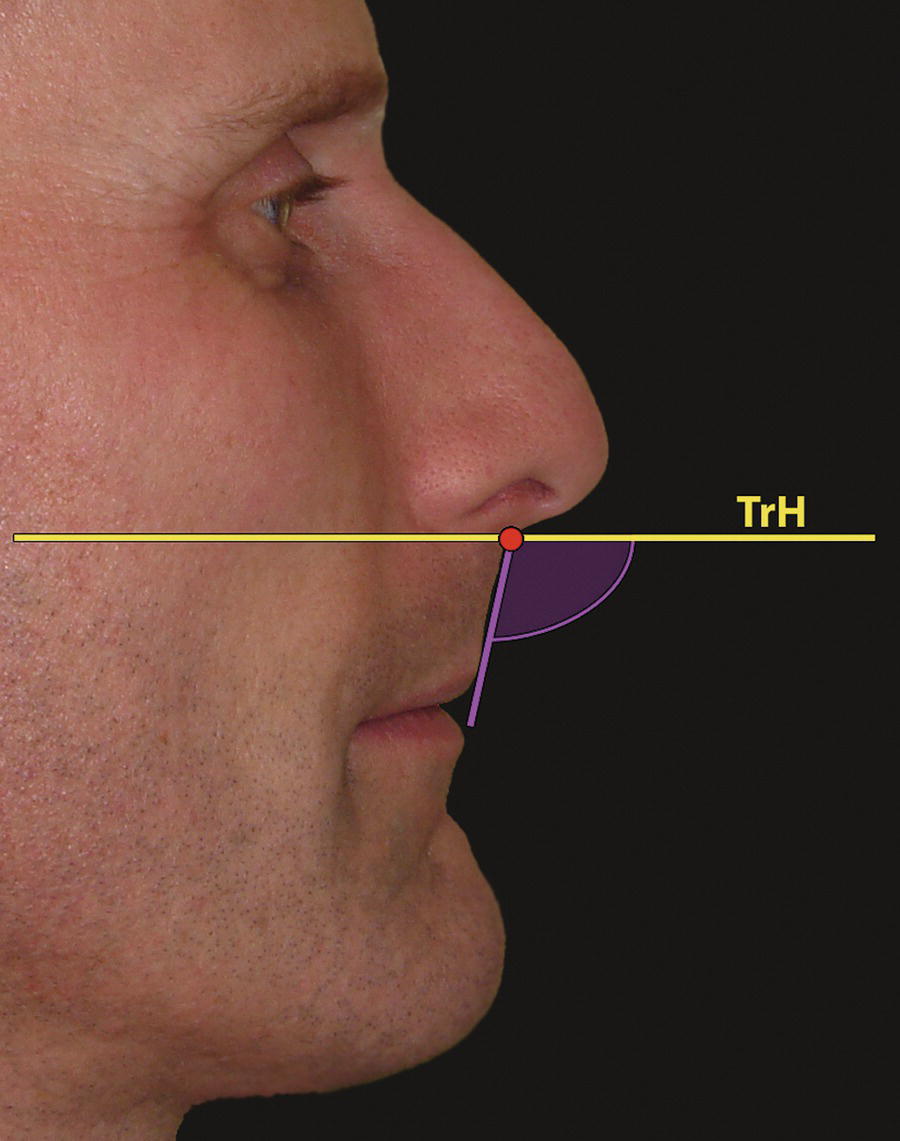

The terms ‘maxilla’ and ‘midface’ are not synonymous. The midface, or middle region of the face, is the area between a superior plane drawn through the zygomaticofrontal sutures and an inferior plane, taken as the maxillary dental–occlusal plane. These planes are not parallel, but converge posteriorly. The midface may therefore be considered a somewhat three‐dimensional triangular region, with its base facing anteriorly. The midfacial region is composed of the two maxillae, the two zygomatic bones, and the naso‐orbito‐ethmoidal complex. This maxillary complex shields the cranium from the masticatory forces of the mandible and provides the dentoskeletal framework over which the midfacial soft tissues drape. Consequently, deformities of the composite midface may involve these structures and their overlying soft tissues to varying extents. The comprehensive aesthetic evaluation of the midface involves the clinical evaluation of the relative size, morphology and position of these structural neighbours. This chapter deals specifically with the clinical evaluation of the maxilla (upper jaw) and its overlying soft tissue drape. In order to successfully correct a dentofacial deformity involving the maxilla, as with any specific region of the craniofacial complex, three systematic steps are required: The description of the initial position and structural relationships of the maxilla and maxillary dentition to the craniofacial complex requires an understanding of specialized vocabulary: Three‐dimensional bodily movement of the maxilla is termed bodily translation, which may occur in the: Maxillary rotation around the three axes of rotation is important mostly in relation to the effect on the maxillary occlusal plane (Figure 16.1A): Figure 16.1 (A) Maxillary rotation around the three axes of rotation. (B) Rotation around the sagittal (x) axis, leading to a transverse cant of the maxillary occlusal plane (requiring roll correction). (C) Rotation around the transverse (y) axis, leading to a difference in the vertical level of the anterior and posterior regions of the maxillary occlusal plane (requiring pitch correction). (D) Rotation around the vertical (z) axis, leading to a maxillary dental midline deviation (requiring yaw correction). This term refers to the movement of a free rigid body in relation to the three planes of space and the three axes of rotation, which are: Planes of space: Axes of rotation: Descriptions of such movements have a long history, with primary descriptions from the Persian astronomer‐scientist Abu Rayhan Biruni (973–1048) and the Persian astronomer‐mathematician Omar Khayyam (1048–1131). However, their descriptions within mathematics and mechanics were formalized by the French mathematician René Descartes (1596–1650) (Latinized name Renatius Cartesius) who pioneered coordinate (analytical) geometry, and after whose Latinized name the Cartesian coordinate system stems, and the Swiss mathematician‐scientist Leonhard Euler (1707–83). Examples of movement in relation to the six degrees of freedom are the motion of a ship at sea or, more famously, the flight dynamics of the space shuttle. The ability of such bodies to change position may be described as: Translational envelopes: Rotational envelopes: This concept is of paramount importance in understanding orthognathic surgical diagnosis and treatment planning. For example, a useful illustrative example involves the repositioning of a Le Fort I osteotomized maxilla. If the maxillary dental arch is level, the maxillary occlusal plane may be thought of as an imaginary table top on which the maxillary dentition sits. Therefore, in relation to the three planes of space, the maxilla and maxillary occlusal plane may be too far forward (prognathic) or too far back (retrognathic), too far up (VMD) or too far down (VME), too far to the left or right (an asymmetry due to bodily translation to the left or right). In relation to the three axes of rotation, the maxilla and maxillary occlusal plane may be rotated around the sagittal axis (i.e. leading to a transverse cant of the maxillary occlusal plane, which would require roll correction to level the cant), rotated around the vertical axis (leading to a midline deviation due to rotation of the skeletal midline, requiring yaw correction), or rotated around the transverse axis, (i.e. posterior aspect at a different vertical level to the anterior, requiring a change in pitch in order to lift the anterior maxilla up or down relative to the posterior maxilla) (Figure 16.1B–D). Every craniofacial unit and subunit may be thought of in this way, aiding both diagnosis and treatment planning. The ‘maxilla’ is the term used to define the upper jaw, which in fact is made up of the two maxillae, each consisting of a body and four processes. The body is roughly pyramidal in shape (Figure 16.2). Its interior is hollowed out by the maxillary paranasal air sinus, alternatively termed the maxillary antrum. The upper (orbital) surface of the body occupies the floor of the orbit; the posterior surface provides the anterior wall of the infratemporal fossa, the medial surface is a major structural component in the wall of the nasal cavity and the anterior surface forms the curved external surface of the upper jaw. Above the incisor teeth, the anterior surface has a shallow depression termed the incisive fossa. Lateral to this is a ridge termed the canine eminence, formed by the root of the canine tooth, which separates the incisive fossa from the further lateral and deeper canine fossa. Above the canine fossa is the infraorbital foramen. The anterior surface ends medially at the pear‐shaped piriform (anterior nasal) aperture, inferior to which the maxillae form a median projection, the anterior nasal spine (ANS). The four maxillary processes are (Figure 16.3): Figure 16.2 Maxilla and midface (frontal view): Figure 16.3 Maxilla: (A) Medial view of left maxilla; (B) Frontal view of left maxilla; (C) Inferior view of bony palate: The patient should be examined in natural head position (NHP), with the mandible in the rest position and the facial soft tissues in repose. The clinical evaluation is essentially in three parts: It is often useful to mask the lower lip and mandibular region when evaluating the midface, particularly in profile view, in order to reduce the visual influence of the relative position of these lower facial structures (Figure 16.4). Scleral exposure: In a patient with normal midfacial morphology and in NHP there should be no sclera exposed either above or below the irides in a relaxed eyelid position and forward gaze. Increased scleral exposure above the lower eyelid and below the iris of the eye is a sign of sagittal upper midfacial deficiency due to retrusion of the inferior orbital rim (Figure 16.5). Inferior orbital rim projection: Reduced sagittal projection of the inferior orbital rim is an important indicator of midfacial retrusion. In profile view, the most anterior part of the globe of the eye is approximately 2–3 mm anterior to the soft tissue inferior orbital rim, equating to 3–4 mm anterior to the bony inferior orbital rim. The lateral orbital rim will be approximately 12–16 mm behind the most anterior projection of the globe (Figure 16.6) (see Chapter 12, section on ‘Relationship of bony orbit and globe’). Cheek morphology and contour: The soft tissue cheek and its supporting skeletal framework form an important ‘facial aesthetic unit’ of the midfacial region. The borders of the cheek are (Figure 16.7): Figure 16.4 Masking the lower lip and mandibular region with a piece of card when evaluating the midface, particularly in profile view, helps to reduce the visual influence of the relative position of these lower facial structures. Figure 16.5 Increased scleral exposure above the lower eyelid and below the iris of the eye is a sign of sagittal upper midfacial deficiency due to retrusion of the inferior orbital rim. Figure 16.6 Inferior orbital rim projection in relation to the globe and lateral orbital rim. Figure 16.7 The borders of the soft tissue cheek. (Modified, detail, Head of a Girl, Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1483; Biblioteca Reale, Turin.) The soft tissue cheek is supported by the maxilla and malar bones, the associated muscles, subcutaneous tissues, the malar fat pad and the buccal fat pad. The buccal fat pad is a component of the face that is essentially independent of the degree of generalized body fat. When excessive, removal of the pad may help to ‘skeletonize’ the midface, but age‐related changes must be taken into account. Ptosis of the pad may occur with advancing age, increasing the inferior cheek volume lateral to the mandibular body and amplifying the appearance of jowling. Combined with the generalized atrophy of midfacial fat and descent of midfacial soft tissues that occurs with age, a resultant submalar concavity may occur, which may be accentuated if the buccal fat pad has been removed previously. Midfacial soft tissue deficiencies tend to be located within an area described as the submalar triangle (Figure 16.8).1 This inverted triangular area of midfacial depression is bordered medially by the nasolabial fold, superiorly by the malar eminence and laterally by the masseter muscle. If the midfacial soft tissue descent and volume loss associated with ageing occurs in a patient with underlying zygomaticomaxillary skeletal deficiency, the result will be an excessively hollow overall midfacial appearance, with deep folds and wrinkles. In patients with malar prominence, the result will be depressions in the submalar region. Accurate diagnosis of such conditions is required and management tends to centre on a combination of midfacial lifting, augmentation and rhytidectomy. Midfacial curvilinear relationship: A midfacial curvilinear contour line may be seen, originating in the soft tissues overlying the zygomatic arch, extending anteriorly along the arch then anteromedially and subsequently inferiorly to the subpupil region (located in line with the pupil of the eye, midway between the inferior orbital rim and the nasal base) over the soft tissues of the cheek, down to the paranasal region (Figure 16.9). From here the line extends inferolaterally along the lateral aspect of the upper lip, ending just lateral to the oral commissure. The line should form a smooth, uninterrupted convex curve. An interruption of this line constitutes a contour defect, which may signify an underlying skeletal deformity, e.g. a contour defect in the paranasal region is a sign of sagittal maxillary deficiency. Figure 16.8 The submalar triangle (1) is bordered superiorly by the malar eminence (2), medially by the nasolabial fold (3) and laterally by the masseter muscle (4). Paranasal area: The paranasal region of interest is that just lateral to the nasal alae. The paranasal region ideally should be slightly convex. Sagittal maxillary deficiency often results in flattening or even concavity of this region, described as paranasal hollowing (Figure 16.10). Nasal base support: The nasal base is supported by the maxilla. Therefore, flatness or concavity of the nasal base region is an indication or maxillary deficiency (Figure 16.11). Nasal projection: In profile view, the ratio of the horizontal linear distance from nasal tip (pronasale) to subnasale and from subnasale to alar base crease is approximately 2:1 (Figure 16.12). Assuming that the nose itself is of normal size, a reduction in this ratio may indicate sagittal maxillary deficiency. Figure 16.9 The midfacial curvilinear contour line should form a smooth, uninterrupted convex curve. In this patient with sagittal maxillary deficiency, there is a concave contour defect of this line (yellow) in the subpupil and paranasal regions, which should follow the broken green convex contour on the figure. (A and B) Frontal view. (D and E) profile view. (C and F) Following maxillary advancement, the subpupil and paranasal regions are convex. Figure 16.10 Paranasal hollowing. (A) Paranasal region is concave as a result of sagittal maxillary deficiency, described as paranasal hollowing. (B) Maxillary advancement resulting in convexity of the paranasal region. Figure 16.11 Nasal base support: Sagittal maxillary deficiency may result in flatness or concavity of the nasal base region. Figure 16.12 The ratio of the horizontal linear distance from nasal tip (pronasale) to subnasale (x) and from subnasale to alar base crease (y) is approximately 2:1; if the nose itself is of normal size, a reduction in this ratio may indicate sagittal maxillary deficiency. Upper lip prominence: The prominence of the upper lip is related to the sagittal position of the maxilla and maxillary dentoalveolus, albeit variable depending on the upper lip thickness. A retrusive upper lip may be a sign of sagittal maxillary deficiency, and a protrusive upper lip a sign of sagittal maxillary excess. Upper lip inclination: The inclination of the upper lip provides an indication of the relative sagittal prominence of the maxillary dentoalveolus. Figure 16.13 Upper lip inclination may be evaluated using a line tangent to the upper lip (labrale superius to subnasale) extended to intersect the N‐perpendicular. Upper lip support: The support for the upper lip is provided by the anterior maxillary dentoalveolus, but also depends to a great extent on the upper lip thickness and the amount of space in the upper labial sulcus between the inner surface of the upper lip and the anterior surface of the maxillary dentoalveolus. Figure 16.14 Nasolabial angle (lower component): the inclination of the upper lip may be evaluated in relation to a true horizontal plane (TrH) through subnasale. In this case, the inclination of the nasal columella is normal, but the upper lip is posteriorly inclined. The maxillary canine root is the longest of any tooth. The canine eminence is a bulge on the alveolar bone overlying the roots of the canine teeth, separating the incisive fossa anteriorly from the deeper canine fossa posteriorly (Figure 16.2). The canine eminence provides a degree of support to the upper lip, though this depends on the thickness of the upper lip. Therefore, in patients with relatively thin lips, extraction of the maxillary canine is best avoided.

Chapter 16

The Maxilla and Midface

Introduction

Terminology

Terms of jaw position in the sagittal plane

Terms of maxillary position in the vertical plane

Terms of jaw size

Terms of maxillary bodily movement in the three planes of space

Terms of maxillary rotation around the three axes of rotation

The six degrees of freedom

Anatomy

Clinical evaluation

Sagittal midfacial‐maxillary evaluation

Soft tissue evaluation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree