Introduction36

INTRODUCTION

Fig. 3.1

Disease

Histopathological features

Lichen planus

Prominent Civatte bodies, band-like inflammatory infiltrate, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis. Hypertrophic form has changes limited to the tips of the acanthotic downgrowths and often superadded lichen simplex chronicus. The infiltrate extends around hair follicles in lichen planopilaris. Pigment incontinence is conspicuous in erythema dyschromicum perstans.

Lichen nitidus

Focal (papular) lichenoid lesions; some giant cells; dermal infiltrate often ‘clasped’ by acanthotic downgrowths.

Lichen striatus

Clinically linear; irregular and discontinuous lichenoid reaction; infiltrate sometimes around follicles and sweat glands.

Lichen planus-like keratosis

Solitary; prominent Civatte body formation; solar lentigo often at margins.

Lichenoid drug eruptions

Focal parakeratosis; eosinophils, plasma cells and melanin incontinence may be features. Deep extension of the infiltrate occurs in photolichenoid lesions.

Fixed drug eruptions

Interface-obscuring infiltrate, often extends deeper than erythema multiforme; cell death often above basal layer; neutrophils often present.

Erythema multiforme

Interface-obscuring infiltrate; sometimes subepidermal vesiculation and variable epidermal cell death.

Graft-versus-host disease

Basal vacuolation; scattered apoptotic keratinocytes, sometimes with attached lymphocytes (‘satellite cell necrosis’); variable lymphocytic infiltrate.

Lupus erythematosus

Mixed vacuolar change and Civatte bodies. SLE has prominent vacuolar change and minimal cell death. Discoid lupus away from the face has more cell death and superficial and deep infiltrate; mucin; follicular plugging; basement membrane thickening. Some cases resemble erythema multiforme with cell death at all layers.

Dermatomyositis

May resemble acute lupus with vacuolar change, epidermal atrophy, some dermal mucin; infiltrate usually superficial and often sparse.

Poikilodermas

Vacuolar change; telangiectasia; pigment incontinence; late dermal sclerosis.

Pityriasis lichenoides

Acute form combines lymphocytic vasculitis with epidermal cell death; interface-obscuring infiltrate; focal hemorrhage; focal parakeratosis.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus

Erythema multiforme-like changes with suprabasal acantholysis and clefting; subepidermal clefting sometimes present.

Pathological change

Possible diagnoses

Vacuolar change

Lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, drugs and poikiloderma

Interface-obscuring infiltrate

Erythema multiforme, fixed drug eruption, pityriasis lichenoides (acute), paraneoplastic pemphigus, lupus erythematosus (some)

Purpura

Lichenoid purpura

Cornoid lamella

Porokeratosis

Deep dermal infiltrate

Lupus erythematosus, syphilis, drugs, photolichenoid eruption

‘Satellite cell necrosis’

Graft-versus-host disease, eruption of lymphocyte recovery, erythema multiforme, paraneoplastic pemphigus, regressing plane warts, drug reactions

High apoptosis

Phototoxic reactions, adult-onset Still’s disease, acrokeratosis paraneoplastica

Prominent pigment incontinence

Poikiloderma, drugs, ‘racial pigmentation’ and an associated lichenoid reaction, erythema dyschromicum perstans and related entities

Eccrine duct involvement

Erythema multiforme (drug induced), lichen striatus, keratosis lichenoides chronica, periflexural exanthem of childhood

Additional pattern

Possible diagnoses

Spongiotic

Drug reactions (see spongiotic drug reactions), lichenoid contact dermatitis, lichen striatus, late-stage pityriasis rosea, superantigen ‘id’ reactions

Granulomatous

Lichen nitidus, lichen striatus (rare), lichenoid sarcoidosis, hepatobiliary disease, endocrinopathies, infective reactions including secondary syphilis, herpes zoster infection, HIV infection, tinea capitis, Mycobacterium marinum, and M. haemophilum; drug reactions (often in setting of Crohn’s disease or rheumatoid arthritis – atenolol, allopurinol, captopril, cimetidine, enalapril, hydroxychloroquine, simvastatin, sulfa drugs, tetracycline, diclofenac, erythropoietin)

Vasculitic

Pityriasis lichenoides, perniosis (some cases), pigmented purpuric dermatosis (lichenoid variant), persistent viral reactions, including herpes simplex

Vasculitic/spongiotic

Gianotti–Crosti syndrome, some other viral/putative viral diseases, rare drug reactions

LICHENOID (INTERFACE) DERMATOSES

LICHEN PLANUS

Treatment of lichen planus

Histopathology167

Fig. 3.2

Fig. 3.3

Fig. 3.4

Fig. 3.5

Electron microscopy

LICHEN PLANUS VARIANTS

Atrophic lichen planus

Histopathology

Hypertrophic lichen planus

Histopathology

Fig. 3.6

Fig. 3.7

Annular lichen planus

Linear lichen planus

Ulcerative (erosive) lichen planus

Histopathology

Oral lichen planus

Histopathology

Lichen planus erythematosus

Histopathology

Erythema dyschromicum perstans

Histopathology254

Fig. 3.8

Lichen planus actinicus

Histopathology287

Lichen planopilaris

Histopathology298.299. and 302.

Fig. 3.9

Lichen planus pemphigoides

Histopathology

Electron microscopy

Keratosis lichenoides chronica

Histopathology

Lupus erythematosus–lichen planus overlap syndrome

LICHEN NITIDUS

Histopathology

Fig. 3.10

Electron microscopy

LICHEN STRIATUS

Histopathology427.453.454. and 455.

Fig. 3.11

Electron microscopy

LICHEN PLANUS-LIKE KERATOSIS (BENIGN LICHENOID KERATOSIS)

Histopathology462.463. and 474.

Fig. 3.12

Fig. 3.13

Fig. 3.14

The early/interface variant is more likely to be a reflection of the underlying lesion undergoing regression, rather than a variant sui generis.

Classic

Atrophic

Atypical (MF-like)

Bullous

TEN-like

‘Creeping’

Lupus stimulant

LICHENOID DRUG ERUPTIONS

Lichen planus pemphigoides: cinnarizine, ramipril

Lichenoid drug eruption: acetylsalicyclic acid, adalimumab, amlodipine, antimalarials, arsenicals, beta-blockers, captopril, carbamazepine, chlorpropamide, cyanamide, dactinomycin, dapsone, docetaxel, doxorubicin, enalapril, etanercept, ethambutol, glimepiride, gold, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (local), hepatitis B vaccination, imatinib, indapamide, indoramin, infliximab, interferon alfa-2b, intravenous immunoglobulins, iodides, lansoprazole, mercury, metformin, methyldopa, naproxen, nicorandil, omeprazole, orlistat, pantoprazole, penicillamine, phenothiazine, pravastatin, quinidine, quinine, salsalate, simvastatin, spironolactone, streptomycin, suramin, terazosin, ticlopidine, tiopronin, valproic acid

Photolichenoid drug eruption: clopidogrel, nimesulide, pyrazinamide, solifenacin, sparfloxacin, tetracycline, thiazides, torsemide

Fixed drug eruption: acetaminophen (paracetamol), acetaminophen/indomethacin/granisetron/IL-2 combination, acetylsalicyclic acid, amoxicillin, amplodipine, antimalarials, antituberculous drugs, carbamazepine, celecoxib, cetirizine, chlormezanone, ciprofloxacin, clarithromycin, clioquinol, colchicine, cotrimoxazole, dextromethorphan, diltiazem, dimenhydrinate, diphenhydramine, enalapril, eperisone hydrochloride, erythromycin, etodolac, feprazone, fluconazole, fluoxetine, griseofulvin, ibuprofen, influenza vaccine, interferon-β, iomeprol, itraconazole, ketoconazole, lactose, lamotrigine, lansoprazole, levocetirizine, mefenamic acid, metamizole, metronidazole, minocycline, naproxen, nimesulide, nystatin, omeprazole, paclitaxel, penicillin, phenolphthalein, phenylbutazone, phenylpropanolamine hydrochloride, phenytoin, piroxicam, pseudoephedrine, quinine, rifampicin, S-carboxymethyl-L-cysteine, sulfamethoxazole, sulfonamides, tartrazene, temazepam, tenoxicam, terbinafine, tetracyclines, theophylline, ticlopidine, tinidazole, topotecan, tranexamic acid, tranquilizers, trimethoprim, tropisetron, vancomycin

Erythema multiforme/TEN: acarbose, acetaminophen (paracetamol), alfuzosin, allopurinol, amifostine, aminopenicillins, amphetamines, ampicillin/sulbactam, bezafibrate, bupropion, carbamazepine, ceftazidime, chloroquine, cimetidine, ciprofloxacin, citalopram, clarithromycin, clindamycin, clobazam, clonazepam, cocaine, colchicine, corticosteroid, cyclophosphamide, cytosine arabinoside, diacerein, doxycycline, escitalopram, ethambutol, etretinate, famotidine, fenoterol, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, gemeprost, griseofulvin, hydroxychloroquine, imatinib, indapamide, indomethacin, iopentol, irbesartan, isoniazid, isoxicam, lamotrigine, lansoprazole, latanoprost eye drops, leflunomide, mefloquine, methotrexate, mifepristone, moxifloxacin, nevirapine, nitrogen mustard, nystatin, ofloxacin, oxaprozin, oxazepam, pantoprazole, paroxetine, phenylbutazone, phenytoin, piroxicam, progesterone, pseudoephedrine, ramipril, ranitidine, ritodrine, rituximab, rofecoxib, sennoside, sertraline, sorafenib, sulfamethoxazole, suramin, telithromycin, terbinafine, tetrazepam, thalidomide, theophylline, thiacetazone, ticlopidine, tramadol, trichloroethylene, trimethoprim, valdecoxib, valproic acid, vancomycin, voriconazole, zonisamide

Subacute lupus erythematosus: adalimumab, anastrozole, antihistamines, bupropion, calcium channel blockers, capecitabine, captopril, cilazapril, cinnarizine, diltiazem, efalizumab, etanercept, griseofulvin, infliximab, leflunomide, naproxen, nifedipine, oxyprenolol, phenytoin, piroxicam, ranitidine, simvastatin, terbinafine, thiazides, ticlopidine, tiotropium, verapamil

Systemic lupus erythematosus: allopurinol, atenolol, captopril, carbamazepine, chlorpromazine, clonidine, danazol, etanercept, ethosuximide, griseofulvin, hydralazine, hydrochlorothiazide, isoniazid, lithium, lovastatin, mesalazine, methimazole, methyldopa, minocycline, penicillin, penicillamine, phenobarbital, phenylbutazone, phenytoin, piroxicam, practolol, primidone, procainamide, propylthiouracil, quinidine, rifampicin, streptomycin, sulfonamides, terbinafine, tetracycline derivatives, thiamazole, trimethadione, valproate

Histopathology492. and 565.

Fig. 3.15

Fig. 3.16

FIXED DRUG ERUPTIONS

Histopathology573. and 685.

Fig. 3.17

Fig. 3.18

Electron microscopy

ERYTHEMA MULTIFORME

Clinical variants

Etiology and pathogenesis

Histopathology690.835. and 836.

Fig. 3.19

Fig. 3.20

Toxic epidermal necrolysis

Treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis

Histopathology855. and 967.

Fig. 3.21

GRAFT-VERSUS-HOST DISEASE

Histopathology978. and 1060.

Fig. 3.22

Grade 0:

normal skin

Grade 1:

basal vacuolar change

Grade 2:

dyskeratotic cells in the epidermis and/or follicle, dermal lymphocytic infiltrate

Grade 3:

fusion of basilar vacuoles to form clefts and microvesicles

Grade 4:

separation of epidermis from dermis.

Electron microscopy

ERUPTION OF LYMPHOCYTE RECOVERY

Histopathology

AIDS INTERFACE DERMATITIS

LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Discoid lupus erythematosus

Treatment of discoid lupus erythematosus

Histopathology1097. and 1207.

Fig. 3.23

Fig. 3.24

Fig. 3.25

Fig. 3.26

Subacute lupus erythematosus

Treatment of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

Histopathology1305

Fig. 3.27

Fig. 3.28

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Investigations

Etiology

Treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus

Histopathology1097

Fig. 3.29

LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS VARIANTS

Neonatal lupus erythematosus

Bullous lupus erythematosus

Fig. 3.30

Lupus panniculitis

DERMATOMYOSITIS

Treatment of dermatomyositis

Histopathology1689

Fig. 3.31

Fig. 3.32

POIKILODERMAS

Fig. 3.33

POIKILODERMA CONGENITALE (ROTHMUND–THOMSON SYNDROME)

Histopathology

Hereditary sclerosing poikiloderma

KINDLER’S SYNDROME

Histopathology

CONGENITAL TELANGIECTATIC ERYTHEMA (BLOOM’S SYNDROME)

Histopathology

DYSKERATOSIS CONGENITA

OMIM

Inheritance

Gene defect

Gene product

Locus

Alternative name

305000

X-linked

DKC1

Dyskerin

Xq28

Zinsser–Cole–Engman syndrome

127550

AD

TERC

Telomerase RNA component

3q21–q28

Scoggins type

AD

TERT

Telomerase reverse transcriptase

5p15.33

AD

TINF2

?

14q11.2 (14q12?)

224230

AR

NOPIO (NOLA3)

?

15q14–q15

Nil

Histopathology

POIKILODERMA OF CIVATTE

Histopathology

OTHER LICHENOID (INTERFACE) DISEASES

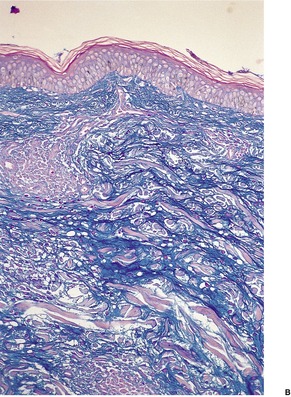

LICHEN SCLEROSUS ET ATROPHICUS

PITYRIASIS LICHENOIDES

Fig. 3.34

PERSISTENT VIRAL REACTIONS

PERNIOSIS

PARANEOPLASTIC PEMPHIGUS

LICHENOID PURPURA

LICHENOID CONTACT DERMATITIS

STILL’S DISEASE (ADULT ONSET)

LATE SECONDARY SYPHILIS

POROKERATOSIS

DRUG ERUPTIONS

PHOTOTOXIC DERMATITIS

PRURIGO PIGMENTOSA

ERYTHRODERMA

MYCOSIS FUNGOIDES

REGRESSING WARTS AND TUMORS

LICHEN AMYLOIDOSUS

VITILIGO

LICHENOID TATTOO REACTION

MISCELLANEOUS CONDITIONS

LICHENOID AND GRANULOMATOUS DERMATITIS

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The lichenoid reaction pattern (‘interface dermatitis’)

Lichenoid (interface) dermatoses38

Lichen planus38

Lichen planus variants40

Atrophic lichen planus40

Hypertrophic lichen planus40

Annular lichen planus41

Linear lichen planus41

Ulcerative (erosive) lichen planus41

Oral lichen planus41

Lichen planus erythematosus42

Erythema dyschromicum perstans42

Lichen planus actinicus43

Lichen planopilaris43

Lichen planus pemphigoides43

Keratosis lichenoides chronica44

Lupus erythematosus–lichen planus overlap syndrome45

Lichen nitidus45

Lichen striatus45

Lichen planus-like keratosis (benign lichenoid keratosis)47

Lichenoid drug eruptions48

Fixed drug eruptions50

Graft-versus-host disease55

Eruption of lymphocyte recovery57

AIDS interface dermatitis57

Dermatomyositis64

Other lichenoid (interface) diseases68

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus69

Pityriasis lichenoides69

Persistent viral reactions69

Perniosis69

Paraneoplastic pemphigus69

Lichenoid purpura69

Lichenoid contact dermatitis69

Still’s disease (adult onset)69

Late secondary syphilis69

Porokeratosis69

Drug eruptions70

Phototoxic dermatitis70

Prurigo pigmentosa70

Erythroderma70

Mycosis fungoides70

Regressing warts and tumors70

Lichen amyloidosus70

Vitiligo70

Lichenoid tattoo reaction70

Miscellaneous conditions70

Lichenoid and granulomatous dermatitis70

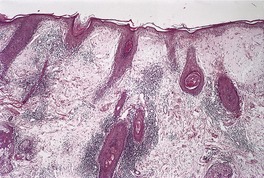

The lichenoid reaction pattern (lichenoid tissue reaction, interface dermatitis) is characterized histologically by epidermal basal cell damage.1.2. and 3. This takes the form of cell death and/or vacuolar change (liquefaction degeneration). The cell death usually involves only scattered cells in the basal layer which become shrunken with eosinophilic cytoplasm. These cells, which have been called Civatte bodies, often contain pyknotic nuclear remnants. Sometimes, fine focusing up and down will reveal smaller cell fragments, often without nuclear remnants, adjacent to the more obvious Civatte bodies. 4 These smaller fragments have separated from the larger bodies during the process of cell death. Ultrastructural studies have shown that the basal cells in the lichenoid reaction pattern usually die by apoptosis, a comparatively recently described form of cell death, which is quite distinct morphologically from necrosis.5. and 6.

Before discussing the features of apoptosis, mention will be made of the term ‘interface dermatitis’, which is widely used. It has been defined as a dermatosis in which the infiltrate (usually composed mostly of lymphocytes) appears ‘to obscure the junction when sections are observed at scanning magnification’. 7 The term is not used uniformly or consistently. Some apply it to most dermatoses with the lichenoid tissue reaction. Others use it for the subgroup in which the infiltrate truly obscures the interface (erythema multiforme, fixed drug eruption, paraneoplastic pemphigus, some cases of subacute lupus erythematosus and pityriasis lichenoides). The infiltrate may obscure the interface in lymphomatoid papulosis, but basal cell damage is not invariable. Many apply the term, also, to lichen planus and variants, in which the infiltrate characteristically ‘hugs’ the basal layer without much extension into the epidermis beyond the basal layer. Crowson et al have expanded the concept of interface dermatitis to include neutrophilic and lymphohistiocytic forms, in addition to the traditional lymphocytic type. They also subdivide the lymphocytic type into a cell-poor type and a cell-rich type. 8 Erythema multiforme, which they list as a cell-poor variant, is sometimes quite ‘cell rich’. The author prefers the traditional term ‘lichenoid’ for this group of dermatoses because it is applicable more consistently than interface dermatitis and it is less likely to be applied as a ‘final sign-out diagnosis’, which is often the case with the term interface dermatitis. The term is so entrenched that it is unlikely to disappear from the lexicon of dermatopathology.

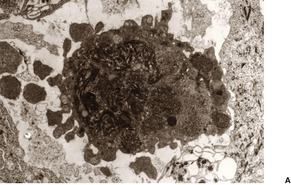

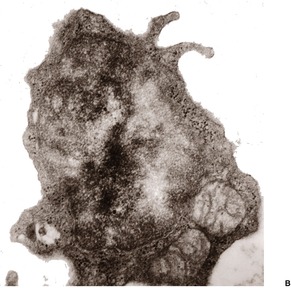

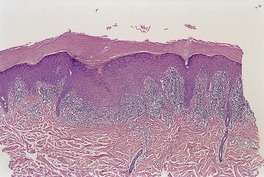

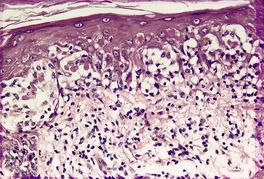

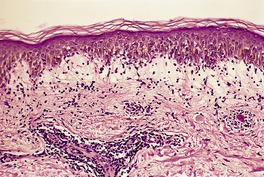

In apoptosis, single cells become condensed and then fragment into small bodies by an active budding process (Fig. 3.1). In the skin, these condensed apoptotic bodies are known as Civatte bodies (see above). The smaller apoptotic bodies, some of which are beyond the resolution of the light microscope, are usually phagocytosed quickly by adjacent parenchymal cells or by tissue macrophages. 5 Cell membranes and organelles remain intact for some time in apoptosis, in contradistinction to necrosis where breakdown of these structures is an integral and prominent part of the process. Keratinocytes contain tonofilaments which act as a ‘straitjacket’ within the cell, and therefore budding and fragmentation are less complete in the skin than they are in other cells in the body undergoing death by apoptosis. This is particularly so if the keratinocyte has accumulated filaments in its cytoplasm, as occurs with its progressive maturation in the epidermis. The term ‘dyskeratotic cell’ is usually used for these degenerate keratinocytes. The apoptotic bodies that are rich in tonofilaments are usually larger than the others; they tend to ‘resist’ phagocytosis by parenchymal cells, although some are phagocytosed by macrophages. Others are extruded into the papillary dermis, where they are known as colloid bodies. These bodies appear to trap immunoglobulins non-specifically, particularly the IgM molecule, which is larger than the others. Apoptotic cells can be labeled by the TUNEL reaction. 9

(A) Apoptosis of a basal keratinocyte in lichen planus. There is surface budding and some redistribution of organelles within the cytoplasm. Electron micrograph ×12 000. (B) A tiny budding fragment in which the mitochondria have intact cristae. (×25 000)

Some of the diseases included within the lichenoid reaction pattern show necrosis of the epidermis rather than apoptosis; in others, the cells have accumulated so many cytoplasmic filaments prior to death that the actual mechanism – apoptosis or necrosis – cannot be discerned by light or electron microscopy. The term ‘filamentous degeneration’ has been suggested for these cells; 10 on light microscopy, they are referred to as ‘dyskeratotic cells’ (see above). Some dermatopathologists use the term ‘necrotic keratinocyte’ for these cells and, also, for keratinocytes that are obviously apoptotic. It should be noted that apoptotic keratinocytes have been seen in normal skin, indicating that cell deletion also occurs as a normal physiological phenomenon.11.12. and 13. As Afford and Randhawa have so eloquently stated ‘Apoptosis is the genetically regulated form of cell death that permits the safe disposal of cells at the point in time when they have fulfilled their intended biological function.’14 It also plays a role in the elimination of the inflammatory infiltrate at the end stages of wound healing. 15

Although it is beyond the scope of this book, readers interested in apoptosis and the intricate mechanisms of its control should read the excellent studies published on this topic.16.17.18.19.20.21.22.23. and 24. The various ‘death receptors’, essential effectors of any programmed cell death, were reviewed in 2003. 25 An important member of this group is tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) which preferentially induces apoptosis in transformed but not normal cells. It is expressed in normal skin and cutaneous inflammatory diseases. 26 Another cell component that plays a role in apoptosis is the mitochondrion. This topic was reviewed in 2006. 27

Ackerman has continued to present a minority view that apoptosis is a type of necrosis. 28 In reality, each is a distinctive form of cell death.

Vacuolar change (liquefaction degeneration) is often an integral part of the basal damage in the lichenoid reaction. Sometimes it is more prominent than the cell death. It results from intracellular vacuole formation and edema, as well as from separation of the lamina densa from the plasma membrane of the basal cells. Vacuolar change is usually prominent in lupus erythematosus, particularly the acute systemic form, and in dermatomyositis and some drug reactions.

As a consequence of the basal cell damage, there is variable melanin incontinence resulting from interference with melanin transfer from melanocytes to keratinocytes, as well as from the death of cells in the basal layer. 1 Melanin incontinence is particularly prominent in some drug-induced and solar-related lichenoid lesions, as well as in patients with marked racial pigmentation.

Another feature of the lichenoid reaction pattern is a variable inflammatory cell infiltrate. This varies in composition, density and distribution according to the disease. An assessment of these characteristics is important in distinguishing the various lichenoid dermatoses. As apoptosis, unlike necrosis, does not itself evoke an inflammatory response, it can be surmised that the infiltrate in those diseases with prominent apoptosis is of pathogenetic significance and not a secondary event. 5 Furthermore, apoptosis is the usual method of cell death resulting from cell-mediated mechanisms, whereas necrosis and possibly vacuolar change result from humoral factors, including the deposition of immune complexes.

One study has given some insight into the possible mechanisms involved in the variability of expression of the lichenoid tissue reaction in several of the diseases within this group. The study examined the patterns of expression of the intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1). 29 Keratinocytes in normal epidermis have a low constitutive expression of ICAM-1, rendering the normal epidermis resistant to interaction with leukocytes. Therefore, induction of ICAM-1 expression may be an important factor in the induction of leukocyte-dependent damage to keratinocytes. 29 In lichen planus, ICAM-1 expression is limited to basal keratinocytes, while in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus there is diffuse epidermal ICAM-1 expression, sometimes with basal accentuation. This pattern is induced by ultraviolet radiation and possibly mediated by tumor necrosis factor-α. In erythema multiforme, there is strong basal expression of ICAM-1, with cell surface accentuation and similar pockets of suprabasal expression, probably induced by herpes simplex virus infection. 29

In summary, the lichenoid reaction pattern includes a heterogeneous group of diseases which have in common basal cell damage. 30 The histogenesis is also diverse and includes cell-mediated and humoral immune reactions and possibly ischemia in one condition. A discussion of the mechanisms involved in producing apoptosis is included in several of the diseases that follow. Scattered apoptotic keratinocytes can also be seen in the sunburn reaction in response to ultraviolet radiation;31. and 32. these cells are known as ‘sunburn cells’. 33 A specific histological diagnosis can usually be made by attention to such factors as:

A discussion of the various lichenoid (interface) dermatoses follows. The conditions listed as ‘other lichenoid (interface) diseases’ are discussed only briefly as they are considered in detail in other chapters.

Lichen planus, a relatively common eruption of unknown etiology, displays violaceous, flat-topped papules, which are usually pruritic.35. and 36. A network of fine white lines (Wickham’s striae) may be seen on the surface of the papules. There is a predilection for the flexor surface of the wrists, the trunk, the thighs, and the genitalia. Palmoplantar lichen planus appears to be more common than once thought.37. and 38. It is one of the most disabling, painful, and therapy-resistant variants of lichen planus. 39 Oral lesions are common; rarely, the esophagus is also involved.40. and 41. Lesions localized to the lip, 42 vulva,43. and 44. and to an eyelid45 have been reported. Lichen planus localized to a radiation field may represent an isomorphic response.46. and 47. It has also developed in a healed herpes zoster scar. 48 Nail changes occur49.50.51. and 52. and, as with oral lesions, these may be the only manifestations of the disease.53. and 54. Clinical variants include atrophic, annular, hypertrophic, linear, zosteriform,55.56. and 57. erosive, oral, actinic, follicular, erythematous, and bullous variants. They are discussed further below. An eruptive variant also occurs. 58 Spontaneous resolution of lichen planus is usual within 12 months, although postinflammatory pigmentation may persist for some time afterwards. 59

Familial cases are uncommon, and rarely these are associated with HLA-D7.60.61.62. and 63. An association with HLA-DR1 has been found in non-familial cases. 64 There is an increased frequency of HLA-DR6 in Italian patients with hepatitis C virus-associated oral lichen planus. 65 Lichen planus is rare in children,66.67.68.69.70.71.72. and 73. but some large series have been published.74.75. and 76. Lichen planus has been reported in association with immunodeficiency states, 77 internal malignancy,78. and 79. including thymoma, 80 primary biliary cirrhosis,81. and 82. peptic ulcer (but not Helicobacter pylori infection), 83 chronic hepatitis C infection,84.85.86.87.88.89.90.91.92.93. and 94. hepatitis B vaccination,95.96.97.98.99.100.101.102.103. and 104. herpesvirus type 7 (HHV-7) replication, 105 simultaneous measles-mumps-rubella and diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis-polio vaccinations, 106 stress, 107 vitiligo, 108 pemphigus, 109 porphyria cutanea tarda, 110 radiotherapy, 111 ulcerative colitis, 112 chronic giardiasis, 113 a Becker’s nevus, 114 and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with coexisting morphea. 115 Despite the association between lichen planus and hepatitis C (HCV) infection, its incidence in patients with lichen planus in some parts of the world is not increased when compared with a control group.116. and 117. The exacerbation or appearance of lichen planus during the treatment of HCV infection and other diseases with alpha-interferon has been reported. 118 Furthermore effective therapy for the HCV does not clear the lichen planus. 119 Reports linking lichen planus to infection with human papillomavirus may be a false-positive result.120. and 121. Squamous cell carcinoma is a rare complication of the oral and vulval cases of lichen planus and of the hypertrophic and ulcerative variants (see below).122.123.124.125. and 126. A contact allergy to metals, flavorings and plastics may be important in the etiology of oral lichen planus. 127 The role of mercury in dental amalgams is discussed further below.

Cell-mediated immune reactions appear to be important in the pathogenesis of lichen planus. 128 It has been suggested that these reactions are precipitated by an alteration in the antigenicity of epidermal keratinocytes, possibly caused by a virus or a drug or by an allogeneic cell. 129 Keratinocytes in lichen planus express HLA-DR on their surface and this may be one of the antigens which has an inductive or perpetuating role in the process.130.131. and 132. Keratinocytes also express fetal cytokeratins (CK13 and CK8/18) but whether they are responsible for triggering the T-cell response is speculative. 133 The cellular response, initially, consists of CD4+ lymphocytes; 134 they are also increased in the peripheral blood. 135 In recent years attention has focused on the role of cytotoxic CD8+ lymphocytes in a number of cell-mediated immune reactions in the skin. They appear to play a significant role as the effector cell, whereas the CD4+ lymphocyte, usually present in greater numbers, 136 plays its traditional ‘helper’ role. In lichen planus, CD8+ cells appear to recognize an antigen associated with MHC class I on lesional keratinocytes, resulting in their death by apoptosis. 137Bcl-2, a proto-oncogene that protects cells from apoptosis, is increased in lichen planus. 138 It may allow some cells to escape apoptosis, prolonging the inflammatory process. 138 The recruitment of lymphocytes to the interface region may be the result of the chemokine MIG (monokine induced by interferon-γ). 139 Lymphokines produced by these T lymphocytes, including interferon-γ, interleukins-1β, -4 and -6, perforin, 140 granzyme B, 141 granulysin, 142 T-cell-restricted intracellular antigen (Tia-1), and tumor necrosis factor, may have an effector role in producing the apoptosis of keratinocytes.143. and 144. The other pathway involves the binding of Fas ligand to Fas, which triggers a caspase cascade.145. and 146. Gene expression profiling in lichen planus has found that type I IFN inducible genes are significantly expressed. 147 Plasmacytoid dendritic cells appear to be a major source of these type I interferons in lichen planus. They play a major role in cytotoxic skin inflammation by increasing the expression of IPIO/CXCRIO and recruiting effector cells via CXCR3. 148 The CXCR3 ligand, CXCL9, is the most significant marker for lichen planus. 147 A unique subclass of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (γδ) is also found in established lesions. 149 Langerhans cells are increased and it has been suggested that these cells initially process the foreign antigen. 131 Factor XIIIa-positive cells and macrophages expressing lysozyme are found in the dermis. 134

Increased oxidative stress, increased lipid peroxidation, and an imbalance in the antioxidant defense system are present, but their exact role in the pathogenesis of lichen planus is unknown. 150

Matrix metalloproteinases may play a concurrent role by destroying the basement membrane. 151 Evidence from an animal model suggests that keratinocytes require cell survival signals, derived from the basement membrane, to prevent the onset of apoptosis. 152 In oral lichen planus, MMP-1 and MMP-3 may be principally associated with erosion development. 153 Altered levels of heat shock proteins are found in the epidermis in lichen planus. 154

Most studies have found no autoantibodies and no alteration in serum immunoglobulins in lichen planus. 155 However, a lichen planus-specific antigen has been detected in the epidermis and a circulating antibody to it has been found in the serum of individuals with lichen planus.156. and 157. Its pathogenetic significance remains uncertain. Antibodies to desmoplakins I and II have been found in oral and genital lesions, possibly representing epitope spreading. 158

Replacement of the damaged basal cells is achieved by an increase in actively dividing keratinocytes in both the epidermis and the skin appendages. This is reflected in the pattern of keratin expression, which resembles that seen in wound healing; cytokeratin 17 (CK17) is found in suprabasal keratinocytes. 159

Potent topical corticosteroids remain the treatment of choice for lichen planus in patients with classic and localized disease. For widespread disease and mucosal lesions, a short course of systemic corticosteroids may provide some relief. 160 Cyclosporine (ciclosporin), hydroxychloroquine, retinoids, dapsone, mycophenolate mofetil, 161 sulfasalazine, 162 alefacept, 163 and efalizumab164 have all been used at various times. Erosive oral disease has been treated with tacrolimus mouthwash, 165 while erosive flexural lichen planus has responded to thalidomide and 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. 166 Palmoplantar disease may be resistant to treatment and require cyclosporine. 38

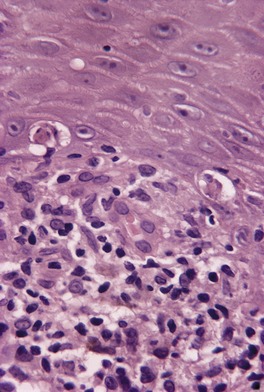

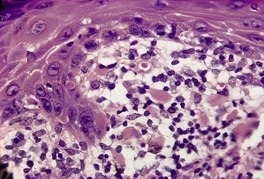

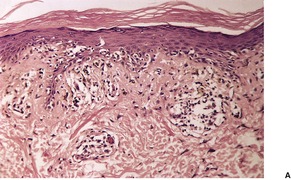

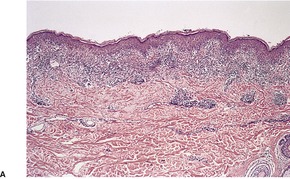

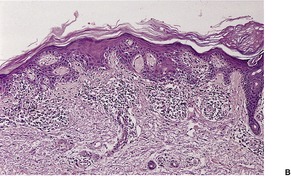

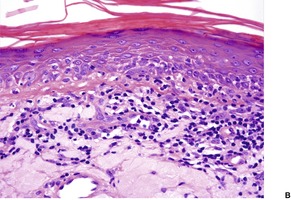

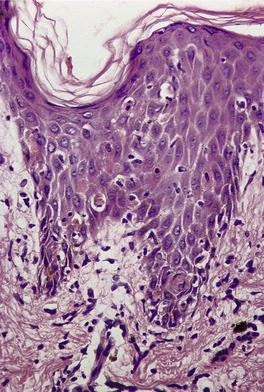

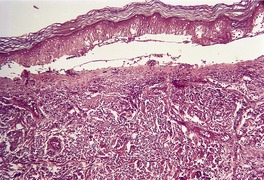

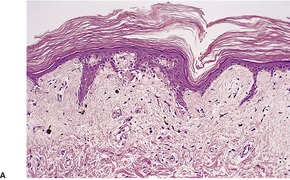

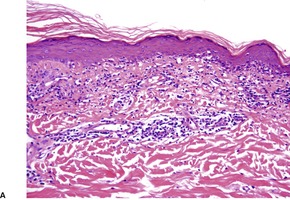

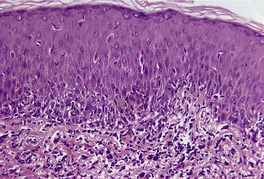

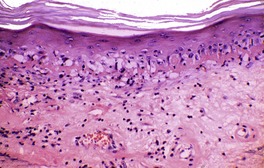

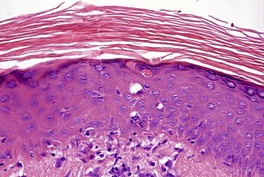

The basal cell damage in lichen planus takes the form of multiple, scattered Civatte bodies (Fig. 3.2). Eosinophilic colloid bodies, which are PAS positive and diastase resistant, are found in the papillary dermis (Fig. 3.3). They measure approximately 20 µm in diameter. The basal damage is associated with a band-like infiltrate of lymphocytes and some macrophages which press against the undersurface of the epidermis (Fig. 3.4). Occasional lymphocytes extend into the basal layer, where they may be found in close contact with basal cells and sometimes with Civatte bodies. The infiltrate does not obscure the interface or extend into the mid-epidermis, as in erythema multiforme and fixed drug eruptions. Karyorrhexis is sometimes seen in the dermal infiltrate. 168 Rarely, plasma cells are prominent in the cutaneous lesions;169.170.171. and 172. they are invariably present in lesions adjacent to or on mucous membranes. There is variable melanin incontinence but this is most conspicuous in lesions of long duration and in dark-skinned people.

Lichen planus. Two apoptotic keratinocytes (Civatte bodies) are present in the basal layer of the epidermis. An infiltrate of lymphocytes touches the undersurface of the epidermis. (H & E)

Lichen planus. There are numerous colloid bodies in the papillary dermis. (H & E)

Lichen planus. A band-like infiltrate of lymphocytes fills the papillary dermis and touches the undersurface of the epidermis. (H & E)

Other characteristic epidermal changes include hyperkeratosis, wedge-shaped areas of hypergranulosis related to the acrosyringia and acrotrichia, and variable acanthosis. At times the rete ridges become pointed, imparting a ‘saw tooth’ appearance to the lower epidermis. There is sometimes mild hypereosinophilia of keratinocytes in the malpighian layer. Small clefts (Caspary–Joseph spaces) 173 may form at the dermoepidermal junction secondary to the basal damage. The eccrine duct adjacent to the acrosyringium is sometimes involved. 174 A variant in which the lichenoid changes were localized entirely to the acrosyringium has been reported. 175 Transepidermal elimination with perforation is another rare finding. 176 The formation of milia may be a late complication. 177

Ragaz and Ackerman have studied the evolution of lesions in lichen planus. 167 They found an increased number of Langerhans cells in the epidermis in the very earliest lesions, before there was any significant infiltrate of inflammatory cells in the dermis. In resolving lesions, the infiltrate is less dense and there may be minimal extension of the inflammatory infiltrate into the reticular dermis.

As already mentioned, some diseases exhibiting the lichenoid tissue reaction may also show features of another tissue reaction pattern as a major or minor feature. These conditions are listed in Table 3.3.

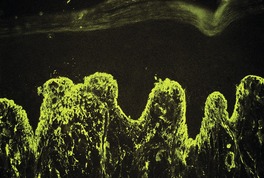

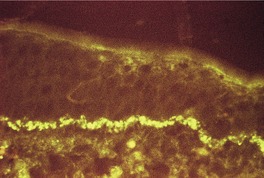

Direct immunofluorescence of involved skin shows colloid bodies in the papillary dermis, staining for complement and immunoglobulins, particularly IgM. An irregular band of fibrin is present along the basal layer in most cases. Often there is irregular extension of the fibrin into the underlying papillary dermis (Fig. 3.5). A recent study has found colloid bodies in 60% of cases of lichen planus, while fibrin was present in all cases. 178 Immunofluorescent analysis of the basement membrane zone, using a range of antibodies, suggests that disruption occurs in the lamina lucida region. 179 Other studies have shown a disturbance in the epithelial anchoring system. 180

Lichen planus. A band of fibrin involves the basement membrane zone and extends into the papillary dermis. (Direct immunofluorescence)

Ultrastructural studies have confirmed that lymphocytes attach to basal keratinocytes, resulting in their death by apoptosis.4.5. and 181. Many cell fragments, beyond the limit of resolution of the light microscope, are formed during the budding of the dying cells. The cell fragments are phagocytosed by adjacent keratinocytes and macrophages. 182 The large tonofilament-rich bodies that result from redistribution of tonofilaments during cell fragmentation appear to resist phagocytosis and are extruded into the upper dermis, where they are recognized on light microscopy as colloid bodies. 183 Various studies have confirmed the epidermal origin of these colloid bodies.184. and 185. There is a suggestion from some experimental work that sublethal injury to keratinocytes may lead to the accumulation of tonofilaments in their cytoplasm. Some apoptotic bodies contain more filaments than would be accounted for by a simple redistribution of the usual tonofilament content of the cell.

A number of clinical variants of lichen planus occur. In some, typical lesions of lichen planus are also present. These variants are discussed in further detail below.

Atrophic lesions may resemble porokeratosis clinically. Typical papules of lichen planus are usually present at the margins. A rare form of atrophic lichen planus is composed of annular lesions.186.187.188.189. and 190. It is composed of violaceous plaques of annular morphology with central atrophy. 191 Hypertrophic lichen planus has been reported at the edge of a plaque of annular atrophic lichen planus. 192 Experimentally, there is an impaired capacity of the atrophic epithelium to maintain a regenerative steady state.

The epidermis is thin and there is loss of the normal rete ridge pattern. The infiltrate is usually less dense than in typical lichen planus. It may be lost in the center of the lesions.

Hypertrophic lesions are usually confined to the shins, although sometimes they are more generalized. They appear as single or multiple pruritic plaques, which may have a verrucous appearance; 193 they usually persist for many years. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma develops in lesions of long standing.194.195.196. and 197. Cutaneous horns, keratoacanthoma, and verrucous carcinoma may also develop in hypertrophic lichen planus.198.199. and 200.

Hypertrophic lichen planus has been reported in several patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. 201 It also occurs in patients with HCV infection. 202 It may occur in children. 203

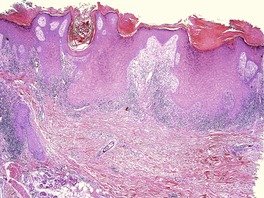

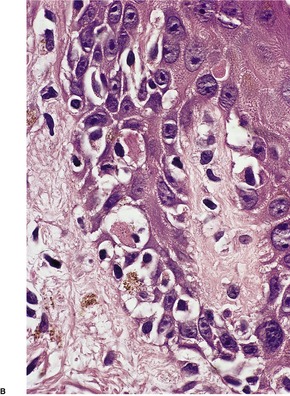

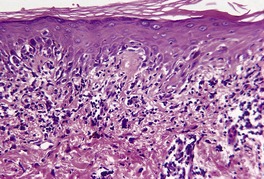

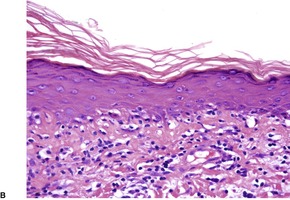

The epidermis shows prominent hyperplasia and overlying orthokeratosis (Fig. 3.6). At the margins there is usually psoriasiform hyperplasia representing concomitant changes of lichen simplex chronicus secondary to the rubbing and scratching. If the epidermal hyperplasia is severe it may mimic a squamous cell carcinoma on a shave biopsy. 204 Vertically oriented collagen (‘vertical-streaked collagen’) is present in the papillary dermis in association with the changes of lichen simplex chronicus.

Hypertrophic lichen planus. The epidermis shows irregular hyperplasia. The dermal infiltrate is concentrated near the tips of the rete ridges. (H & E)

The basal cell damage is usually confined to the tips of the rete ridges and may be missed on casual observation (Fig. 3.7). The infiltrate is not as dense or as band-like as in the usual lesions of lichen planus. A few eosinophils and plasma cells may be seen in some cases in which the ingestion of beta-blockers can sometimes be incriminated.

Hypertrophic lichen planus. There are a number of Civatte bodies near the tips of the rete ridges. (H & E)

Xanthoma cells have been found in the dermis, localized to a plaque of hypertrophic lichen planus, in a patient with secondary hyperlipidemia. 205 This is an example of dystrophic xanthomatization.

Annular lichen planus is one of the rarer clinical forms of lichen planus. In a series of 20 patients, published some years ago, 18 were men and 2 women. Sites of involvement included the axilla, penis, extremities, and groin. 206 Eighteen of the patients had purely annular lesions, whereas two of the patients had a few purple polygonal papules as well. The majority of lesions showed central clearing with a purple to white annular edge. Lesions varied from 0.5 to 2.5 cm in diameter. Atrophic annular lesions were discussed with atrophic lichen planus (see p. 40). The majority of patients were asymptomatic. Oral and genital lesions have been reported in annular lichen planus. 207

The cases reported as annular lichenoid dermatitis of youth appear to be a distinct entity, but further reports will be necessary to clarify its exact position in the spectrum of lichen planus. 208 The lesions are persistent erythematous macules and annular patches mostly localized on the groin and flanks. In all cases the clinical picture has been suggestive of morphea, mycosis fungoides, or annular erythema but these conditions could be excluded on the basis of the distinctive superficial lichenoid reaction with massive necrosis/apoptosis of the keratinocytes at the tips of the rete ridges. 208 Patch testing has given negative results. 209

Linear lichen planus is a rare variant which must be distinguished from linear nevi and other dermatoses with linear variants.210. and 211. It occurs in less than 0.5% of patients with lichen planus. 212 Linear lichen planus usually involves the limbs. It may follow the lines of Blaschko.213. and 214. It has been reported in association with hepatitis C infection, 212 HIV infection, 215 and metastatic carcinoma. 216

Sometimes linear lesions are associated with disseminated non-segmental papules of ordinary lichen planus. The linear lesions are usually more pronounced in these combined cases. 217

Ulcerative lichen planus (erosive lichen planus) is characterized by ulcerated and bullous lesions on the feet.218. and 219. Mucosal lesions, alopecia, and more typical lesions of lichen planus are sometimes present. Squamous cell carcinoma may develop in lesions of long standing. Variants of ulcerative lichen planus involving the perineal region, 220 penis, 221 the mouth, 222 or the vulva, vagina and mouth – the vulvovaginal-gingival syndrome43.223.224.225. and 226. – have been reported. A patient with erosive lesions of the flexures has been reported. 227

Castleman’s tumor (giant lymph node hyperplasia) and malignant lymphoma are rare associations of erosive lichen planus;228. and 229. long-term therapy with hydroxyurea and infection with hepatitis C are others.230. and 231. Screening for hepatitis C and B has not been considered necessary for vulval lichen planus in some countries. 232

Antibodies directed against a nuclear antigen of epithelial cells have been reported in patients with erosive lichen planus of the oral mucosa. 233 Weak circulating basement membrane zone antibodies are also present. 234

High potency topical corticosteroids have been used to treat erosive lichen planus. Relief of symptoms was obtained in 71% of cases of vulvar disease in one series. 235 A good response to topical tacrolimus, particularly in vulvar disease, has been achieved in recent years.236.237.238. and 239. Azathioprine, retinoids, dapsone, methotrexate, and hydroxychloroquine have also been used, but there have been no controlled trials of these various treatments.232. and 240. Photodynamic therapy can also be used.

Penile erosive lichen planus responded to circumcision in one case. 241

There is epidermal ulceration with more typical changes of lichen planus at the margins of the ulcer. Plasma cells are invariably present in cases involving mucosal surfaces. Eosinophils were prominent in the oral lesions of a case associated with methyldopa therapy. In erosive lichen planus of the vulva there is widespread disruption in several basement membrane zone components including hemidesmosomes and anchoring fibrils. 242

Oral lichen planus has a prevalence of about 0.5% to 2%. It is a disease of middle-aged and older persons, with a female predominance. 243 The disease may persist for many years despite treatment. Spontaneous remission is rare. 244

There is a low prevalence of oral lichen planus among hepatitis C (HCV) infected patients;245.246. and 247. the keratotic form of oral lichen planus is more prevalent in this disease. 202

There has been a resurgence of interest in the role of an allergy to mercury in dental amalgams in the pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Dental plaque and calculus, which have also been shown to contain mercury, are also associated with the disease. 248 It appears that in cases unassociated with cutaneous lichen planus, oral lichen planus may often be cleared by the partial or complete removal of amalgam fillings, if there is a positive patch test reaction to mercury compounds.243. and 249. Because mercury-associated disease does not have all the clinical and/or histological features of oral lichen planus, the term ‘oral lichenoid lesion’ is sometimes used for these cases. 247 In one case lichen planus developed in a herpes zoster scar on the face following an amalgam (mercury) filling. 250 Oral squamous cell carcinoma is a rare complication of oral lichen planus. 244 It appears that desmocollin-1 expression in oral atrophic lichen planus is a powerful predictor of the development of dysplasia, while desmocollin-1 and E-cadherin expression are predictors of the development of cancer. 251

Oral lichen planus mimics to varying degrees the changes seen in cutaneous disease. The infiltrate is usually quite heavy, and it may contain plasma cells, particularly in erosive forms when neutrophils may also be present. Both cells are also found in amalgam-associated disease. Apoptotic keratinocytes tend to occur at a slightly higher level in the mucosa than they do in the cutaneous form, possibly a reflection of amalgam-related cases. Features said to be more likely in amalgam-associated disease are: deep extension of the infiltrate, perivascular extension of the infiltrate, and the presence of plasma cells and neutrophils in the connective tissue. 252

Lichen planus erythematosus has been challenged as an entity. Non-pruritic, red papules, with a predilection for the forearms, have been described. 193

A proliferation of blood vessels may be seen in the upper dermis in addition to the usual features of lichen planus.

Erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis, lichen planus pigmentosus) 253 is a slowly progressive, asymptomatic, ash-colored or brown macular hyperpigmentation254.255. and 256. which has been reported from most parts of the world; it is most prevalent in Latin America. 257 Lesions are often quite widespread, although there is a predilection for the trunk and upper limbs. Unilateral258 and linear lesions259 have been described. Periorbital hyperpigmentation is a rare presentation of this disease. 260 Activity of the disease may cease after several years. Resolution is more likely in children than in adults.261. and 262. Recently, it has been proposed that ‘erythema dyschromicum perstans’ should be used when lesions have, or have previously had, an erythematous border, while ‘ashy dermatosis’ should be used for other cases without this feature. 263 Most clinicians regard the terms as synonymous.

Erythema dyschromicum perstans has been regarded as a macular variant of lichen planus264 on the basis of the simultaneous occurrence of both conditions in several patients256.265. and 266. and similar immunopathological findings.267. and 268. Both paraphenylenediamine, and aminopenicillins have been incriminated in its etiology,261. and 264. although this has not been confirmed. This condition has also been reported in patients with HIV infection, 269 and with HCV infection. 270 There appears to be a genetic susceptibility to the disease. In one Mexican study, there was a significant increase in HLA-DR4, particularly the *0407 subtype, in patients with the disease. 257

Lichen planus pigmentosus, originally reported from India, is thought by some to be the same condition,255. and 264. although this has been disputed.263.271.272. and 273. A linear variant has been reported. 274 In a study of 124 patients with lichen planus pigmentosus from India, the face and neck were the commonest sites affected with pigmentation varying from slate gray to brownish-black. 275 Lichen planus was also present in 19 patients. 275 The term ‘lichen planus pigmentosus inversus’ has been used for cases with predominant localization of the disease in intertriginous areas.276.277. and 278. Lichen planus pigmentosus has been reported in association with a head and neck cancer and with concurrent acrokeratosis paraneoplastica (see p. 506). Both conditions cleared after treatment of the cancer. 279

Various therapies have been tried for erythema dyschromicum perstans, but with little benefit. They include sun protection, chemical peels, corticosteroids, and chloroquine. 280 Some patients have responded to dapsone, 280 and to clofazimine. 281

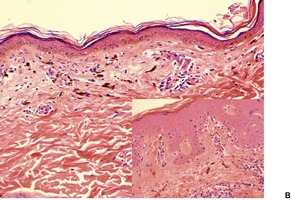

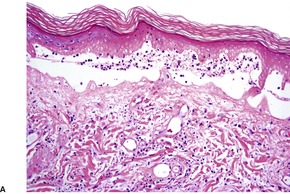

In the active phase, there is a lichenoid tissue reaction with basal vacuolar change and occasional Civatte bodies (Fig. 3.8). The infiltrate is usually quite mild in comparison to lichen planus. Furthermore, there may be deeper extension of the infiltrate, which is usually perivascular. There may also be mild exocytosis of lymphocytes. 273 There is prominent melanin incontinence and this is the only significant feature in older lesions. Subepidermal fibrosis was present in one case. 282 The pigment usually extends deeper in the dermis than in postinflammatory pigmentation of other causes. 271 Cases reported as lichen planus pigmentosus (see above) have similar histological features. 272

Erythema dyschromicum perstans. (A) There is patchy basal cell damage and some pigment incontinence. (B) Another case of ‘ashy dermatosis’ which has almost ‘burnt-out’. There is marked melanin incontinence. (H & E)

Immunofluorescence has shown IgM, IgG, and complement-containing colloid bodies in the dermis, as in lichen planus. There was a predominance of CD8+ lymphocytes in the dermis in one study. 273 The exocytosing lymphocytes expressed cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA). 273 Apoptosis and residual filamentous bodies are present on electron microscopy. 254

Lichen planus actinicus is a distinct clinical variant of lichen planus in which lesions are limited to sun-exposed areas of the body.283. and 284. It has a predilection for certain races, 285 particularly young individuals of Oriental origin. There is some variability in the clinical expression of the disease in different countries and this has contributed to the proliferation of terms used – lichen planus tropicus, 286 lichen planus subtropicus, 287 lichenoid melanodermatitis, 288 and summertime actinic lichenoid eruption (SALE).284. and 289. More recently it has been suggested that SALE is an actinic variant of lichen nitidus. The development of pigmentation in some cases290 has also led to the suggestion that there is overlap with erythema dyschromicum perstans (see above). 265 The pigmentation may take the form of melasma-like lesions.291. and 292. Such lesions have also been reported in childhood cases. 74 Lesions have been induced by repeated exposure to ultraviolet radiation. 293

A rare erythematous variant has been described in a patient with chronic active hepatitis B infection. 294

Various treatments have been used including hydroxychloroquine, intralesional corticosteroids combined with topical sunscreens, and retinoids. Oral cyclosporine has also been used. 295

The appearances resemble lichen planus quite closely, 296 although there is usually more marked melanin incontinence284. and 293. and there may be focal parakeratosis. 283 The inflammatory cell infiltrate in lichen planus actinicus is not always as heavy as it is in typical lesions of lichen planus.

Numerous immunoglobulin-coated cytoid bodies are usually present on direct immunofluorescence. 297

Lichen planopilaris (follicular lichen planus) is a clinically heterogeneous variant of lichen planus in which keratotic follicular lesions are present, often in association with other manifestations of lichen planus.298.299. and 300. It typically affects middle-aged women and men. The annual incidence in four US hair research centers varied from 1.15% to 7.59% of new cases, reflecting its relative rarity. 301 The most common and important clinical group is characterized by scarring alopecia of the scalp, which is generalized in about half of these cases. The keratotic follicular lesions and associated erythema are best seen at the margins of the scarring alopecia. 302 In this group, changes of lichen planus are present or develop subsequently in approximately 50% of cases. 302 Rare cases have been reported in children. 303

The Graham Little–Piccardi–Lassueur syndrome is a rare but closely related entity in which there is cicatricial alopecia of the scalp, follicular keratotic lesions of glabrous skin, and variable alopecia of the axillae and groins.300.304.305. and 306. It has been reported in a patient with androgen insensitivity syndrome (testicular feminization). 307

Two other clinical groups occur but they have not received as much attention. 299 In one, there are follicular papules, without scarring, usually on the trunk and extremities. In the other, which is quite rare, there are plaques with follicular papules, usually in the retroauricular region, although other sites can be involved. 299 This variant has been called lichen planus follicularis tumidus. 308

Rare variants of lichen planopilaris include a linear form309.310.311. and 312. and the presence of lesions confined to the vulva. 313 It has been reported in a patient with erythema dyschromicum perstans, 314 and in another with scleroderma en coup de sabre. 315 It has developed in a patient receiving etanercept therapy. 316

Topical corticosteroid therapy (usually high-potency form) and intralesional steroids are the treatments of choice for patients with localized disease, particularly in the early phase.317. and 318. In one series of 30 cases treated with topical corticosteroids, resolution of the inflammatory process and blocking of the cicatricial progression were observed in 66% of cases. 317 A mild reduction occurred in 20% of patients, and no response in 13%. 317 Oral hydroxychloroquine is often used. 319 Tetracyclines appear to be more effective than once thought. 318 Cyclosporine was effective in a patient with the Graham Little–Piccardi–Lassueur syndrome. 306 It has also been used in other forms of lichen planopilaris unresponsive to corticosteroids and hydroxychloroquine. 319 Hair transplants and scalp reductions may be used in inactive end-stage disease. 318

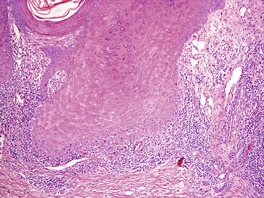

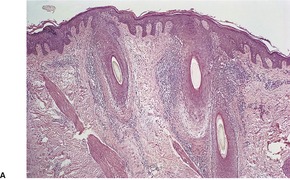

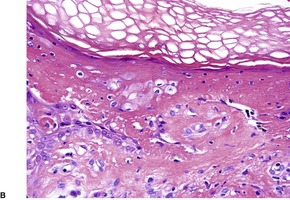

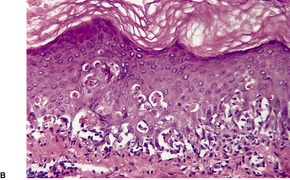

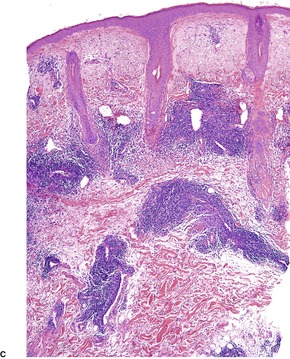

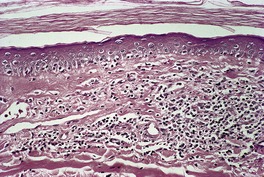

In lichen planopilaris, there is a lichenoid reaction pattern involving the basal layer of the follicular epithelium, with an associated dense perifollicular infiltrate of lymphocytes and a few macrophages (Fig. 3.9). The changes involve the infundibulum and the isthmus of the follicle. A recent study has pointed out that this is the so-called bulge region of the follicle where the stem cells reside. 320 It is the prototypical lymphocytic cicatricial alopecia. 301 Unlike lupus erythematosus, the infiltrate does not extend around blood vessels of the mid and deep plexus. There is also some mucin in the perifollicular fibroplasia, unlike lupus erythematosus in which it is predominantly in the interfollicular dermis. 321 The interfollicular epidermis is involved in up to one-third of cases with scalp involvement,299.302. and 322. and in the rare plaque type (see above). It is not usually involved in the variant with follicular papules on the trunk and extremities. 299 If scarring alopecia develops there is variable perifollicular fibrosis and loss of hair follicles which are replaced by linear tracts of fibrosis. 322 There is also loss of the arrector pili muscles and sebaceous glands. 321 The papillary dermis may also be fibrosed. In advanced cases of scarring alopecia, the diagnostic features may no longer be present. The term ‘pseudopelade’ has been used by some for cases of end-stage scarring alopecia.

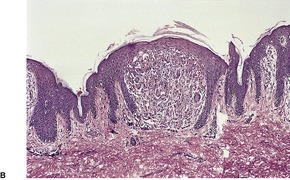

Lichen planopilaris. The lichenoid infiltrate is confined to a perifollicular location. Two different cases – (A) and (B). (H & E)

Direct immunofluorescence shows colloid bodies containing IgG and IgM in the dermis adjacent to the upper portion of the involved follicles.300. and 323. In one report, linear deposits of immunoglobulins were found along the basement membrane of the hair follicles (of the scalp) in all cases. Fibrin was present in one case; cytoid bodies were not demonstrated. 324 It should be noted that the lesions were of long standing (3–7 years). 324

This rare disease is characterized by the coexistence of lichen planus and a heterogeneous group of subepidermal blistering diseases resembling bullous pemphigoid.325.326. and 327. There are tense bullae, often on the extremities, which may develop in normal or erythematous skin or in the lesions of lichen planus.328.329.330. and 331. They do not necessarily recur with subsequent exacerbations of the lichen planus.332. and 333. Oral lesions are exceedingly rare. 334 Lichen planus pemphigoides has been reported in children.332.333. and 335. Rare clinical presentations include a unilateral distribution and onset following PUVA therapy.336. and 337. Similar lesions have been induced by the anti-motion sickness drug cinnarizine and by the ACE inhibitor ramipril.338.339. and 340. Some cases have been reported in association with neoplasia, sharing this characteristic with paraneoplastic pemphigus. 341

Lichen planus pemphigoides is different from bullous lichen planus103. and 342. in which vesicles or bullae develop only in the lichenoid papules, probably as a result of unusually severe basal damage and accompanying dermal edema.343. and 344.

The pathogenesis of lichen planus pemphigoides appears to be due to epitope spreading. It has been suggested that damage to the basal layer in lichen planus may expose or release a basement membrane zone antigen, which leads to the formation of circulating antibodies and consequent blister formation.345.346. and 347. The target antigen is a novel epitope (MCW-4) within the C-terminal NC16A domain of the 180 kDa bullous pemphigoid antigen (BP180, type XVII collagen).348.349. and 350.

Lichenoid erythrodermic bullous pemphigoid is a rare disease reported in African patients. It differs from lichen planus pemphigoides by the presence of a desquamative erythroderma and frequent mucosal lesions. 351

Lichen planus pemphigoides may be treated with topical corticosteroids, systemic steroids, tetracycline and nicotinamide combined, retinoids, and dapsone. 352 Systemic corticosteroids appear to be the most effective treatment for extensive disease. 352

A typical lesion of lichen planus pemphigoides consists of a subepidermal bulla which is cell poor, with only a mild, perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils. 353 The presence of neutrophils and eosinophils has not been mentioned in all reports. Sometimes a lichenoid infiltrate is present at the margins of the blister343 and there are occasional degenerate keratinocytes in the epidermis overlying the blister. 328 Lesions which arise in papules of lichen planus show predominantly the features of lichen planus; a few eosinophils and neutrophils are usually present, in contrast to bullous lichen planus in which they are absent. 328 In one report, a pemphigus vulgaris-like pattern was present in the bullous areas. 354

Direct immunofluorescence of the bullae will usually show IgG, C3, and C9 neoantigen in the basement membrane zone and there is often a circulating antibody to the basement membrane zone.355. and 356. Indirect split-skin immunofluorescence has shown binding to the roof of the split. 346

In lichen planus pemphigoides the split occurs in the lamina lucida, as it does in bullous pemphigoid.346. and 357. Immunoelectron microscopy has shown that the localization of the immune deposits may resemble that seen in bullous pemphigoid, cicatricial pemphigoid, or epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, evidence of a heterogeneous disorder. 358

Keratosis lichenoides chronica is characterized by violaceous, papular, and nodular lesions in a linear and reticulate pattern on the extremities and a seborrheic dermatitis-like facial eruption.359.360.361.362.363.364. and 365. A rare vascular variant with telangiectasias has been reported. 366 Oral ulceration and nail involvement may occur.367. and 368.

It is a rare condition, particularly in children.369.370.371. and 372. It has been suggested that pediatric-onset disease is different from adult-onset keratosis lichenoides chronica. 373 Childhood cases may have familial occurrence, and probably autosomal recessive inheritance. Early or congenital onset with facial erythemato-purpuric macules is sometimes seen. 373 Forehead, eyebrow, and eyelash alopecia are usually present. A case mimicking verrucous secondary syphilis has been reported.374. and 375. The condition is possibly an unusual chronic variant of lichen planus, although this concept has been challenged.376. and 377. Böer believes that there is an authentic and distinctive condition that should continue to be called keratosis lichenoides chronica, but that many of the purported cases are lichen planus, lupus erythematosus, or lichen simplex chronicus. 378

Keratosis lichenoides chronica may be associated with internal diseases such as glomerulonephritis, hypothyroidism, and lymphoproliferative disorders.366.376. and 379. In one patient with multiple myeloma there were eruptive keratoacanthoma-like lesions. 380

The disease is refractory to many different treatment modalities, 366 although calcipotriol or tacalcitol alone, or in combination with oral retinoids, may give good results. 366 Oral retinoids alone are sometimes effective. 381 Phototherapy has also been used. 382

There is a lichenoid reaction pattern with prominent basal cell death and focal basal vacuolar change. 383 The inflammatory infiltrate usually includes a few plasma cells and sometimes there is deeper perivascular and periappendageal cuffing. 384 Telangiectasia of superficial dermal vessels is sometimes noted. 385 Epidermal changes are variable, with alternating areas of atrophy and acanthosis sometimes present, as well as focal parakeratosis. 386 The parakeratosis often has a staggered appearance with neutrophil remnants. 378 Cornoid lamellae and amyloid deposits in the papillary dermis have been recorded. 377 Numerous IgM-containing colloid bodies are usually found on direct immunofluorescence. 367

The term ‘lichen planoporitis’ was used for a case with the clinical features of keratosis lichenoides chronica and histological changes that included a lichenoid reaction centered on the acrosyringium and upper eccrine duct with focal squamous metaplasia of the upper duct and overlying hypergranulosis and keratin plugs. 387 Ruben and LeBoit have also reported eccrine duct involvement in a case of keratosis lichenoides chronica. 388 Böer states that the lichenoid infiltrate in keratosis lichenoides chronica is commonly centered around infundibula and acrosyringia. 378

Lupus erythematosus–lichen planus overlap syndrome is a heterogeneous entity in which one or more of the clinical, histological, and immunopathological features of both diseases are present.389. and 390. Some cases may represent the coexistence of lichen planus and lupus erythematosus, while in others the ultimate diagnosis may depend on the course of the disease.391. and 392. In most cases, the lupus erythematosus is of the chronic discoid or systemic type; rarely, it is of the subacute type. 393 It was the cause of a scarring alopecia in one case. 394 Before the diagnosis of an overlap syndrome is entertained, it should be remembered that some lesions of cutaneous lupus erythematosus may have numerous Civatte bodies and a rather superficial inflammatory cell infiltrate which at first glance may be mistaken for lichen planus. The use of an immunofluorescent technique using patient’s serum and autologous lesional skin as a substrate may assist in the future in elucidating the correct diagnosis in some of these cases. 395

Lichen nitidus is a rare, usually asymptomatic chronic eruption characterized by the presence of multiple, small flesh-colored papules, 1–2 mm in diameter.396. and 397. The lesions have a predilection for the upper extremities, chest, abdomen, and genitalia of children and young adult males.396. and 398. The disorder is most often localized but sometimes lesions are more generalized.399.400. and 401. Familial cases are rare. 402 It has been reported in association with Down syndrome. 403 Nail changes404. and 405. and involvement of the palms and soles406.407. and 408. have been reported. It has been suggested that cases reported in the past as summertime actinic lichenoid eruption (SALE) should be reclassified as actinic lichen nitidus.409.410. and 411. It has been reported in association with lichen spinulosus. 412

Although regarded originally as a variant of lichen planus, lichen nitidus is now considered a distinct entity of unknown etiology. It has followed hepatitis B vaccine. 413 The lymphocytes in the dermal infiltrate in lichen nitidus express different markers from those in lichen planus. 414 Lichen planus has developed subsequent to generalized lichen nitidus in a child. 415

Although spontaneous remissions of lichen nitidus are common, 399 persistent lesions and those that are refractory to various treatments can pose therapeutic challenges. Sometimes resolution is accompanied by postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. 399 Some of the treatments used include systemic and topical corticosteroids, antihistamines, retinoids, low-dose cyclosporine, itraconazole, isoniazid, and ultraviolet therapy.400. and 416. Generalized lichen nitidus has been successfully treated with narrowband-UVB phototherapy.400. and 417.

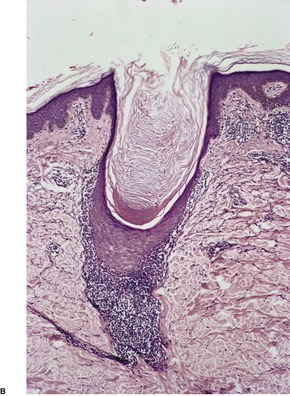

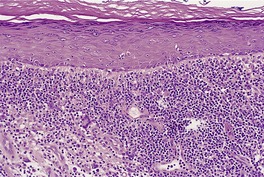

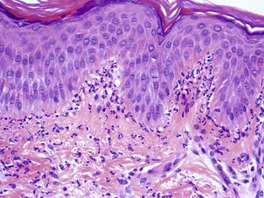

A papule of lichen nitidus shows a dense, well-circumscribed, subepidermal infiltrate, sharply limited to one or two adjacent dermal papillae. 396 Claw-like, acanthotic rete ridges, which appear to grasp the infiltrate, are present at the periphery of the papule (Fig. 3.10). The inflammatory cells push against the undersurface of the epidermis, which may be thinned and show overlying parakeratosis. Occasional Civatte bodies are present in the basal layer.

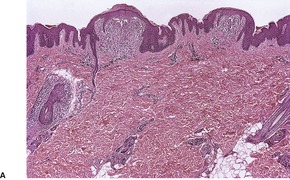

Lichen nitidus. (A) There are two discrete foci of inflammation involving the superficial dermis. (B) Claw-like downgrowths of the rete ridges are present at the margins of these foci. (C) Another case with a broader lesion. (H & E)

In addition to lymphocytes, histiocytes, and melanophages, there are also epithelioid cells and occasional multinucleate giant cells in the inflammatory infiltrate. 418 Rarely, plasma cells are conspicuous. 419 The appearances are sometimes frankly granulomatous and these lesions must be distinguished from disseminated granuloma annulare in which the infiltrate may be superficial and the necrobiosis sometimes quite subtle. Lichen nitidus also needs to be distinguished from an early lesion of lichen scrofulosorum. While the infiltrate in lichen nitidus ‘hugs’ the epidermis and expands the dermal papilla, the granulomas in lichen scrofulosorum do not cause widening of the papillae. Furthermore, in lichen scrofulosorum there may be mild spongiosis and exocytosis of neutrophils into the epidermis. 420

Rare changes that have been reported include subepidermal vesiculation, 421 transepidermal elimination of the inflammatory infiltrate,418.422. and 423. and the presence of perifollicular granulomas. 424 Periappendageal inflammation mimicking lichen striatus has also been reported. 425

Direct immunofluorescence is usually negative, a distinguishing feature from lichen planus.

The ultrastructural changes in lichen nitidus are similar to those of lichen planus. 426

Lichen striatus is a linear, papular eruption of unknown etiology which may extend in a continuous or interrupted fashion along one side of the body, usually the length of an extremity.427. and 428. Annular429 and bilateral forms430 have been reported. The lesions often follow Blaschko’s lines;431.432.433. and 434. this is almost invariable for lesions on the trunk and face. 435 Nail changes are not uncommon,436. and 437. resulting in onychodystrophy. 438 Lichen striatus has a predilection for female children and adolescents. 435 Familial cases are rare. 439 An unusual presentation in children is the presence of linear lesions on the nose with some overlap features with lupus erythematosus. 440 Spontaneous resolution usually occurs after 6 months, although some cases persist longer. 435 Hypochromic sequelae occur in nearly 30% of cases; hyperchromic sequelae are much less common. 435 Relapses are uncommon. A history of atopy is sometimes present in affected individuals.435. and 441.

Lichen striatus has been reported following BCG vaccination, 434 varicella infection, 442 solarium exposure, 443 and following a flu-like illness. 444 It has also developed in a pregnant woman, 445 and in a patient with plaque psoriasis. 446 It has been suggested that lichen striatus represents an autoimmune CD8-mediated response against a mutate keratinocytic clone, which represents a somatic mutation occurring after fertilization. 435

Because lichen striatus usually resolves spontaneously, therapy is not required. 160 Topical steroids have been used to treat the disease, but they do not appear to influence the duration of the lesions. 435 Tacrolimus (0.1%) is an effective treatment option for lichen striatus of the face and other areas.447.448. and 449. Pimecrolimus cream has also been effective in adult patients.450.451. and 452.

There is a lichenoid reaction pattern with an infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and melanophages occupying three or four adjacent dermal papillae. 455 The overlying epidermis is acanthotic with mild spongiosis associated with exocytosis of inflammatory cells. Small intraepidermal vesicles containing Langerhans cells are present in half of the cases. 456 Dyskeratotic cells are often present at all levels of the epidermis; such cells are uncommon in linear lichen planus. 457 There is usually mild hyperkeratosis and focal parakeratosis. 427 The dermal papillae are mildly edematous. The infiltrate is usually less dense than in lichen planus and it may extend around hair follicles or vessels in the mid-plexus. Eccrine extension of the infiltrate is often present (Fig. 3.11).453. and 454. A monoclonal population of T cells has been reported in one case but excluded in others. 458

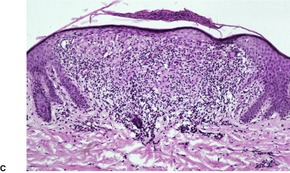

Lichen striatus. This case has a florid perieccrine infiltrate of lymphocytes. (H & E)

It should not be forgotten that lichen striatus has been called a ‘chameleon’. 456 The histology may closely mimic lichen nitidus or lichen planus even though the clinical features are those of lichen striatus. Furthermore, adult blaschkitis has histological overlap features with lichen striatus. 459

Dyskeratotic cells similar to the corps ronds of Darier’s disease have been described in the upper epidermis. 454 The Civatte bodies in the basal layer show the usual changes of apoptosis on electron microscopy.

Lichen planus-like keratosis (LPLK) is a commonly encountered entity in routine histopathology.460.461.462.463.464.465. and 466. Synonyms used for this entity include solitary lichen planus, benign lichenoid keratosis, 461 lichenoid benign keratosis,462. and 463. and involuting lichenoid plaque. 464 It should not be confused with lichenoid actinic (solar) keratosis467 in which epithelial atypia is a prerequisite for diagnosis. 468 Lichen planus-like keratoses are usually solitary, discrete, slightly raised lesions of short duration, measuring 3–10 mm in diameter. Multiple lesions (20–40) have been reported, but the illustration of one such case appears to show a cornoid lamella. 469 In a study of 1040 cases, 8% of patients presented with two lesions, and less than 1% with three lesions. 470 The sudden appearance of the lesion is often a striking feature. Lesions are violaceous or pink, often with a rusty tinge. 460 There may be a thin, overlying scale. The dermoscopic features correlate with the stage of the lesion and the nature of the lesion being regressed.471. and 472. There is a predilection for the arms and presternal area of middle-aged and elderly women. 470 Lesions are sometimes mildly pruritic or ‘burning’. 461 Clinically, LPLK is usually misdiagnosed as a basal cell carcinoma or Bowen’s disease.

Lichen planus-like keratosis is a heterogeneous condition which usually represents the attempted cell-mediated immune rejection of any of several different types of epidermal lesion. In most instances this is a solar lentigo,460.473. and 474. but in some lesions there is a suggestion of an underlying seborrheic keratosis, large cell acanthoma or even a viral wart. 475 Constant pressure was incriminated in one case. 476 Acetaminophen (paracetamol) was incriminated in another case. 477 In one study, a contiguous solar lentigo was present in only 7% of cases and a seborrheic keratosis in 8.4%. 465 These findings do not accord with the author’s own experiences.

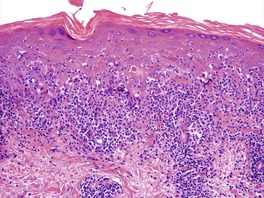

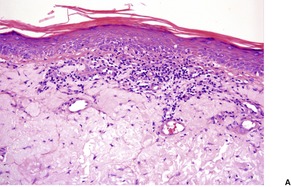

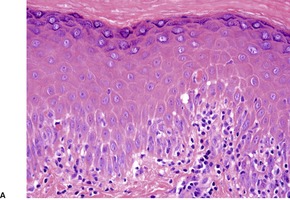

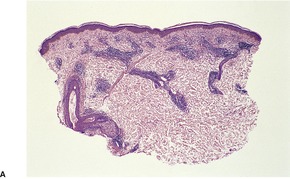

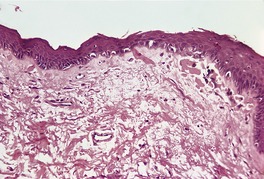

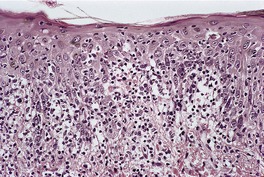

There is a florid lichenoid reaction pattern with numerous apoptotic keratinocytes in the basal layer and accompanying mild vacuolar change (Fig. 3.12). The infiltrate is usually quite dense and often includes a few plasma cells, eosinophils, and even neutrophils in addition to the lymphocytes and macrophages. The infiltrate may obscure the dermoepidermal interface. A rare variant of LPLK has histological features simulating mycosis fungoides. 478 Pautrier-like microabscesses, the alignment of lymphocytes along the basal layer, and epidermotropism are features of this variant. 478 Some of the cells are CD30+. 470

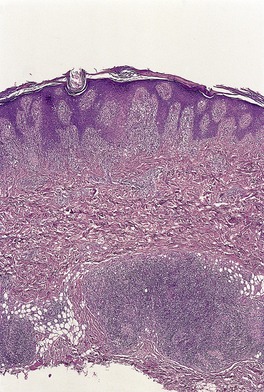

(A) Lichen planus-like keratosis. (B) There is a lichenoid reaction pattern with some deeper extension of the infiltrate than is usual in lichen planus. (H & E)

Pigment incontinence may be prominent. This is so in the late (regressed, atrophic) stage; epidermal atrophy and papillary dermal fibrosis are also present. 470 There may be mild atypia of keratinocytes but this is never as marked as it is in a lichenoid solar keratosis. 32 Before a diagnosis of LPLK is made, the sections should be carefully scanned to ensure that there is not an underlying melanocytic proliferation. 479

There is often mild hyperkeratosis and focal parakeratosis. 465 The presence of parakeratosis allows a distinction to be made with lichen planus. Hypergranulosis is not as pronounced as in lichen planus. A contiguous solar lentigo or large cell acanthoma (Fig. 3.13) is sometimes seen. 480

Lichen planus-like keratosis. It is arising in a large cell acanthoma. (H & E)

Usually cell death is scattered and of apoptotic type. At times confluent necrosis occurs and in these cases subepidermal clefting may result. Sometimes this variant simulates toxic epidermal necrolysis (Fig. 3.14). At other times, the lesions are bullous with a heavy lymphocytic infiltrate and increased numbers of dead basal keratinocytes. 470There is also a rare ‘creeping’ form in which there is focal acute activity and other areas with few lymphocytes, little if any apoptotic cell death, and some melanin incontinence. A careful search for a cornoid lamella of porokeratosis should always be made when these changes are present.

Lichen planus-like keratosis of the toxic epidermal necrolysis type. (A) There is blister formation in this region. (B) Another area of the same case. (H & E)

The attempt to classify ‘lichenoid keratoses’ into three groups – lichen planus-like keratosis, seborrheic keratosis-like lichenoid keratosis, and lupus erythematosus-like lichenoid keratosis – deserves some comment. 481 The seborrheic keratosis-like variant is best called an irritated (lichenoid) seborrheic keratosis and the lupus erythematosus-like variant is simply a lesion with some basal clefting (see above). It may sometimes represent early lupus erythematosus. 482 Notwithstanding this comment, the author admits that making a distinction between LPLK and lupus erythematosus is occasionally difficult for lesions on the face in which the biopsy is small. The presence of follicular involvement in lupus erythematosus and its absence in LPLK is not a reliable point of distinction as some LPLKs can have not only involvement of the infundibula of follicles, but also follicular involvement at a slightly deeper level.

A summary of the histological types of LPLK is shown in Table 3.4.

Direct immunofluorescence shows colloid bodies containing IgM and some basement membrane fibrin. 462 Immunohistochemistry shows fewer Langerhans cells in the epidermis than in lichen planus. 483 The infiltrate is polyclonal. 484

Mention should be made of the report of Melan A-positive pseudonests in the setting of lichenoid inflammation. 485 These nests did not stain for S100 protein or a ‘melanoma cocktail’. 485 A subsequent paper found no Melan A/MART-1 positive pseudonests in lichenoid inflammation. 486

Shave excision is the usual method of treatment for these lesions.

A lichenoid eruption has been reported following the ingestion of a wide range of chemical substances and drugs.487. and 488. The eruption may closely mimic lichen planus clinically, although at other times there is eczematization and more pronounced, residual hyperpigmentation. Rarely the eruption follows Blaschko’s lines. 489 Some of the β-adrenergic blocking agents produce a psoriasiform pattern clinically but lichenoid features histologically.490. and 491. Discontinuation of the drug usually leads to clearing of the rash over a period of several weeks. 492 A lichenoid reaction has developed in a temporary henna tattoo, 493 as well as in permanent tattoos.494. and 495.