and Peter M. Prendergast2

(1)

Elysium Aesthetics, Bogota, Colombia

(2)

Venus Medical, Dublin, Ireland

Introduction

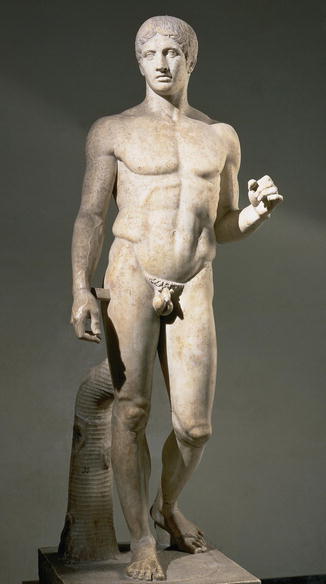

Through the ages, the human form has been featured greatly in the artistic expression of artists and sculptors. In the fifth century BC, the Greek sculptor Polykleitos created Doryphorus, the bronze sculpture that exemplifies the perfectly harmonious and balanced proportions of the human body (Fig. 1.1). This muscular nude male exhibits athletic readiness in classic “contrapposto,” or counterpose, where the arms and shoulders twist off axis to the legs and hips. There is minimal body fat and excellent muscular definition. His contemporary, Phidias, is regarded as one of the greatest sculptors of Classical Greece. Phidias’ colossal chryselephantine and gold statue of Zeus at Olympia was regarded as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

Fig. 1.1

The sculpture Doryphorus, detailing the male form in classic “contrapposto” (Courtesy of Bridgeman Art)

No sculptor could carve such captivating and convincing works of art without having accurate knowledge of the human anatomy. The skin and subcutaneous fat is merely draped over the anatomical wonders beneath. If an artist or sculptor does not know all of the muscles, tendons, and bony landmarks, how can he display them through the skin in his masterpiece? He must also understand their functions and how they change with motion: a muscular body in action is characterized by concavities, convexities, and shadows that instantly portray the state of health. For millennia, the work of Claudius Galen dominated the understanding of anatomy in Europe. Galen (AD 129–201) dissected pigs and primates and demonstrated his findings in numerous texts and treatises. His teachings remained uncontested until 1543, when the influential work of Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius was published, entitled De Humani Corporis Fabrica.

Art and Anatomy

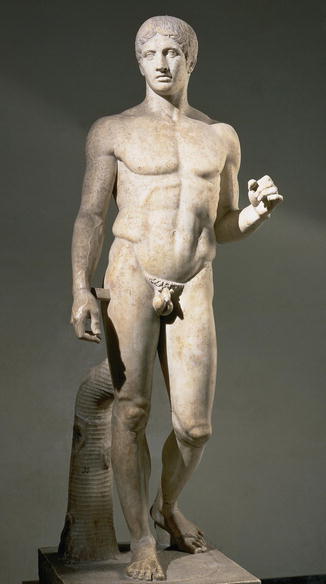

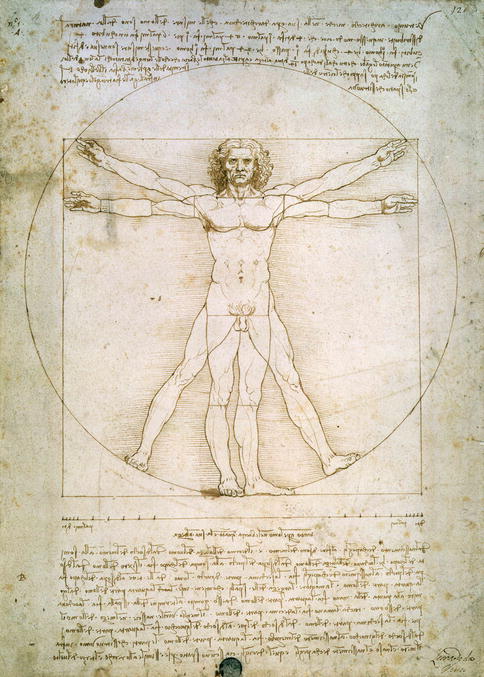

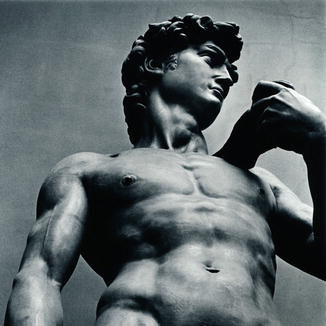

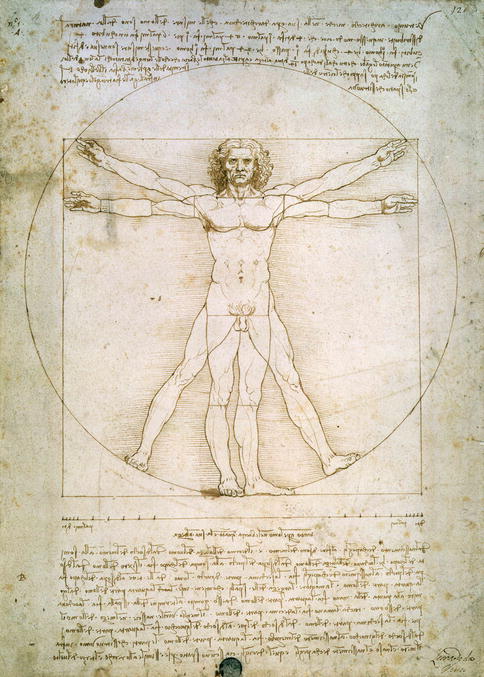

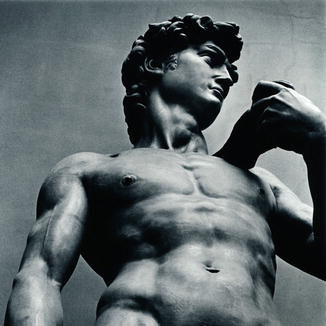

The merging of art and anatomy is perhaps most evident and glorious in the works of Leonardo da Vinci. His anatomical manuscripts are filled with detailed and intricate drawings that elegantly reveal muscular anatomy, symmetry, and human proportions (Fig. 1.2). His knowledge of anatomy was derived from his own independent dissections and research and is elegantly and beautifully portrayed in many of his renowned paintings. Michelangelo similarly celebrated human physicality through his work as an artist and sculptor. David represents one of the most recognized sculptures of the Renaissance and showcases the human body in all its strength, athleticism, and youthful beauty (Fig. 1.3). The muscular definition of deltoid, biceps, pectoralis major, rectus abdominis, and external obliques is clearly visible in Michelangelo’s David.

Fig. 1.2

An example of Leonardo da Vinci’s manuscript showing human anatomy and proportions (Courtesy of Bridgeman Art)

Fig. 1.3

Michelangelo’s David

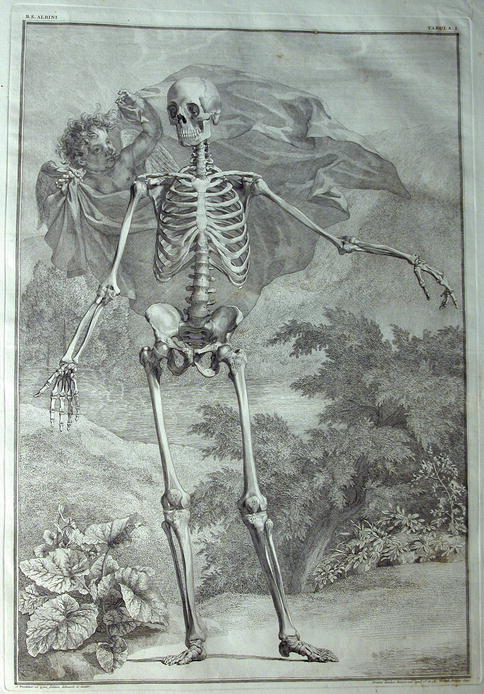

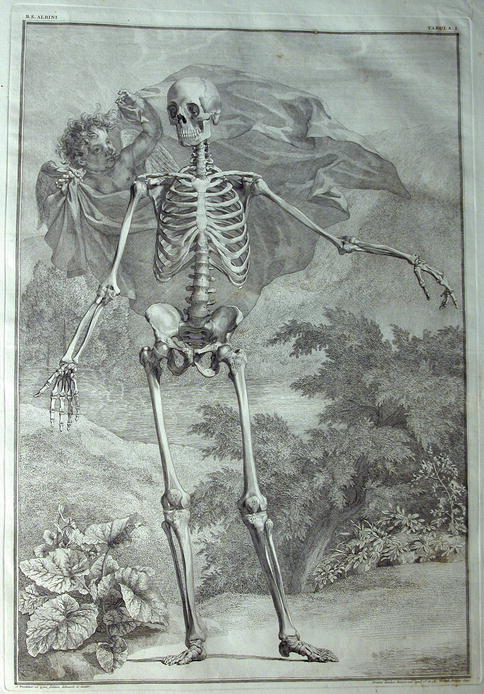

In 1747, the intimate relationship between art and anatomy was again exemplified by the collaborative efforts of artist Jan Wandelaar and anatomist Bernhard Siegfried Albinus [1]. Their atlas, Tabulae Sceleti et Musculorum Corporis Humani, showcases the musculoskeletal system in a series of exquisitely detailed engravings (Fig. 1.4). Further evidence of the importance and prominence of anatomical art in the eighteenth century lies in the works of French artist Jacques Fabien Gautier d’Agoty [1]. D’Agoty’s The Flayed Angel demonstrates the layered architecture of the back musculature by splaying open the superficial layers (Fig. 1.5). We look on in wonder and awe. Our fascination with uncluttered human anatomy continues today and is nurtured by our access to museums and exhibitions that celebrate the human form. These include the Museo Zoologico La Specola at the University of Florence, where hundreds of life-size wax models were sculpted from cadaver dissections between 1771 and 1814. More recently, the exhibition Körperwelten showcases real human specimens that have been preserved by plastination, a technique pioneered by the anatomist Gunther von Hagens. Von Hagens’ work reveals anatomy in motion—running, lifting, stretching, and dancing—and has captivated the public at exhibitions all around the world since 1995.

Fig. 1.4

Engraving of an animated skeleton from Tabulae Sceleti et Musculorum (Courtesy of Bridgeman Art)

Fig. 1.5

D’Agoty’s The Flayed Angel revealing the muscular and bony anatomy of the back (Courtesy of Bridgeman Art)

The celebration of our physicality in the natural world is expressed through our study of anatomy, art, and aesthetics. Since art may be considered the endeavor toward perfection, we may consider artistic body sculpting as an attempt to achieve perfect human form. Although “perfect” human form hardly exists and is in any case subjective, there are several determinants of physical attractiveness as well as aesthetic ideals that we can consider to strive toward our goal of achieving beautiful physical form. These include symmetry, proportions, curves, ratios, and indices.

Greek sculptors and artists strove to reduce what they observed as perfect human form to order, by measuring features and proportions, thus quantifying aesthetic ideals. Phidias used a special ratio, approximating 1.618, for many of his creations. This golden ratio, or phi (ϕ), after Phidias, appears to hold special importance in aesthetics in the natural world.

A beautiful body can be considered to be one that attracts our attention and elicits a positive emotional response. Beauty and function are also intimately related, so that a beautiful body is one that functions well. As humans, we have evolved with finely honed mating strategies, complete with the evolved desire to seek mates who exhibit signs of youth and health. Both sexes have the innate desire to reproduce and to seek mates that exhibit physical signs of reproductive health [2]. These cues to health, strength, and fertility include muscular definition and athleticism in males and curvaceousness in females. The surgeon performing advanced body sculpting aims to improve attractiveness by enhancing muscular definition and curvaceousness.

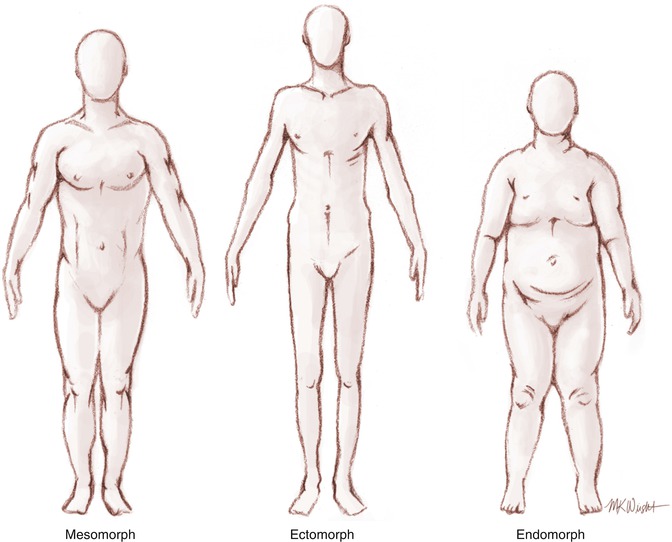

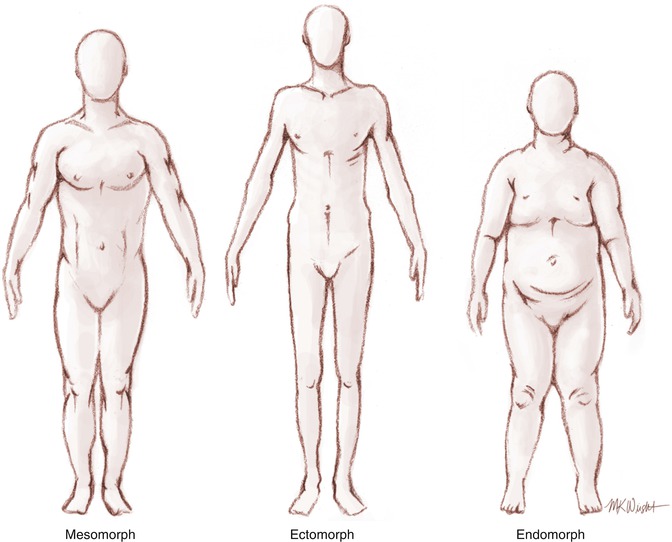

We inherit many physical attributes, including body type and shape. In the 1940s, American psychologist William Sheldon proposed a classification of body types that is still widely used today [3]. This system of somatotypology describes three main body types: ectomorph, mesomorph, and endomorph (Fig. 1.6). An ectomorph is typically tall and thin with low fat content, narrow shoulders, and high metabolism. Ectomorphs find it difficult to gain weight. Mesomorphs are muscular and lean, with medium bones and a solid torso. They may gain some fat if calorific intake is too high or exercise is deficient. Endomorphs have big bones, a wide waist, and a tendency toward fatness. Endomorphs gain weight easily and require high-intensity exercise and dieting to become lean. Through diet and exercise, all body types have the ability to increase muscle tone and mass, reduce body fat, improve posture, and acquire other physical manifestations of health and beauty.

Fig. 1.6

Sheldon’s three main body types

Liposuction Technology and Body Art

For exercise and diet-resistant fatty deposits, liposuction has been utilized as a surgical solution for unwanted convex adiposities for decades. The introduction of the tumescent technique by Klein in the 1990s transformed the safety of suction-assisted lipoplasty [4]. However, traditional liposuction has inherent limitations based on instrumentation and technique, relegating it to a procedure indicated primarily for debulking and unrefined body contouring.

In 2000, Sound Surgical Technologies introduced an efficient third-generation ultrasound-assisted lipoplasty technology called VASER, an acronym for vibration amplification of sound energy at resonance [5]. The introduction of VASER allowed efficient and safe emulsification of fat in deep and superficial planes through cavitation while preserving vascular and neural structures. It also represented the sculptor’s chisel in a new technique that would change the concept of surgical body contouring. Pioneered by Hoyos in 2002, VASER-assisted high-definition lipoplasty (VAHDL) radically altered the tenets of lipoplasty in aesthetic surgery [6]. The human body can be sculpted like a work of art, working in all subcutaneous planes, by adding and subtracting fat with delicate instruments and refined techniques. The subdermal plane is no longer a no-go area, controlled deformities are desirable, and muscular definition is attainable through lipoplasty by revealing the underlying anatomy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree