Classification of Histiocytoses

Langerhans cell disease | |

Xanthogranuloma family | Juvenile xanthogranuloma Papular xanthoma Scalloped cell xanthogranuloma Xanthoma disseminatum Reticulohistiocytoma Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis Spindle cell xanthogranuloma Progressive nodular histiocytosis Benign cephalic histiocytosis Generalized eruptive histiocytosis |

Other histiocytic disorders | Indeterminate cell histiocytosis Rosai–Dorfman disease Erdheim–Chester disease |

Xanthomas associated with lipid abnormalities | Eruptive Tuberous Tendon Plane |

Normolipemic xanthomas | Xanthelasma Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma Diffuse normolipemic plane xanthoma Verruciform xanthoma |

The basic histologic pattern created by macrophages is a granuloma. One variant is a xanthogranuloma which includes lipids as well as macrophages. In addition to the diseases to be discussed in this chapter, a wide array of disorders can display similar histologic patterns. Most are discussed elsewhere in this book.

1. Metabolic disorders: In addition to hyperlipoproteinemias and other disorders of fat metabolism, many lysosomal disorders and other storage diseases may feature cutaneous xanthomas or other infiltrates. The diagnosis of these disorders is not a practical question for the dermatopathologist, and they will not be further considered.

2. Infectious diseases: Tuberculosis, lepromatous leprosy, other mycobacterial infections, and leishmaniasis may produce granulomas.

3. Proliferations: Some lymphomas present with cutaneous granulomatous infiltrates; included in this group are Hodgkin lymphoma and some forms of T-cell lymphoma. Most diseases diagnosed in the past as histiocytic malignancies are lymphomas. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma and its more superficial cutaneous variant atypical fibroxanthoma are established diagnoses, but their line of differentiation remains controversial. Melanocytic lesions can be confused with macrophage disorders, both clinically and histologically. The red-brown color of xanthogranulomas is similar to that of Spitz nevi. Touton giant cells can sometimes be confused with multinucleated rosette cells in melanocytic nevi.

4. Trauma: Most dermatofibromas and some verruciform xanthomas are the result of trauma, be it an insect bite, folliculitis, or another insult. Some xanthomas arise secondary to cutaneous damage from light or after marked inflammation. External objects, such as glass fragments, silica, and many others, may produce cutaneous granulomas, often of the sarcoidal type. A ruptured follicular cyst is also accompanied by a macrophage response.

5. Idiopathic: Unfortunately, most “histiocytic” diseases fit here, and there is little logic to what has been considered a macrophage disorder and what has been classified elsewhere. For example, granuloma annulare has a macrophage infiltrate but is considered a necrobiotic disorder. Both rheumatoid arthritis and sarcoidosis may feature infiltrates of macrophages in the skin and other organs; nonetheless, they are not considered “histiocytoses.”

LANGERHANS CELL DISEASE

Clinical Summary. The clinical spectrum of Langerhans cell disease (LCD) is broad, with skin involvement a common finding. Whereas LCD has been subdivided into several clinical types, overlaps are the rule, not the exception, and lumping appears more appropriate than splitting. Acute disseminated LCD (Abt–Letterer–Siwe disease) usually occurs in infants but can be seen in older children or adults. The most common manifestations are fever, anemia, thrombocytopenia, enlargement of the liver and spleen, and lymphadenopathy. Osteolytic lesions are uncommon except in the mastoid region of the temporal bone, resulting in a clinical picture of otitis media (8). Pulmonary LCD typically occurs in adult smokers, but lung involvement can be seen in children with widespread disease, in whom it is a poor sign.

Cutaneous lesions are found in about 80% of cases, often as a presenting sign. Numerous closely set, red-brown papules covered with scales or crusts may be accompanied by petechiae. This type of eruption may be extensive, involving particularly the scalp, face, and trunk, with a striking resemblance to seborrheic dermatitis. Cutaneous LCD is very pleomorphic; lesions may be vesicular, ulcerated, urticarial, or, rarely, xanthomatous. In the elderly, anogenital involvement is common. If there is a diffuse cutaneous eruption, one must anticipate multiorgan involvement.

Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis (CSHRH) (Hashimoto–Pritzker disease) (9) is another variant of LCD, not a distinct disorder. It is usually present at birth but may not appear until several days or weeks after delivery. Affected infants have scattered papules and nodules. Large nodules tend to become eroded or ulcerated. Usually, the number of lesions varies from several to a dozen; on rare occasions, numerous lesions are widely scattered over the entire skin. In about 25% of cases, a solitary nodule is present. The lesions begin to involute within 2 to 3 months and usually have completely regressed within 12 months. But the patients should be carefully followed up; relapses may occur, including bone involvement, and the occasional case may advance to acute disseminated disease (10,11). Although acute disseminated LCD may also be present at birth, it is rarely nodular.

In chronic multifocal LCD, diabetes insipidus, exophthalmos, and multiple defects of the bones, especially of the cranium, represent the classic triad of Hand–Schüller–Christian disease. Any one or even all three of the cardinal symptoms may be absent, and entirely different organs may be involved. For example, enlargement of the liver, spleen, lungs, or lymph nodes may be found. Osteolytic lesions of the long bones may result in spontaneous fractures. In Hand–Schüller–Christian disease, the diabetes insipidus is caused by granulomatous infiltration of the hypothalamus–pituitary axis; the exophthalmos, by retro-orbital accumulations of granulomatous tissue; and the multiple defects in the skull, by the osteolytic effect of granulomatous infiltrates. Cutaneous lesions occur in about one third of the cases. Three types of skin lesions may be found. Most common are infiltrated nodules and plaques undergoing ulceration, especially in the axillae, the anogenital region, and the mouth. Next in frequency is an extensive eruption identical to that in infants but usually less severe. Finally, in rare instances xanthomas are seen.

Chronic focal LCD or eosinophilic granuloma represents the fourth and least severe variant. The lesions are either solitary or few. Most common are lesions of the bones, but the skin or the oral mucosa is occasionally involved, either with or without osseous lesions. Involvement of the jaw leading to a loose or floating tooth is a fairly typical occurrence. Although the lesions are usually chronic, some heal spontaneously, and simple surgery is generally curative. In rare instances, cases originally diagnosed as chronic focal disease may progress into multifocal or even disseminated disease.

There are a number of unusual cutaneous manifestations of LCD. Mucosal involvement, such as of the lip, has been described (12). Nail changes are also seen, and generally are associated with systemic involvement (13). There are cases where LCD is associated with juvenile xanthogranuloma (14).

The clinical course and the prognosis of LCD are difficult to predict. The most important parameters in prognosis are those recommended for staging: the age of the patient, the number of organs involved, and the degree of organ dysfunction. Abnormalities of the bone marrow, spleen, liver, or lungs suggest a poor prognosis. Skin involvement alone suggests a favorable outcome. Paradoxically, the presence of skin disease at birth (the nodules of CSHRH) is a good sign, but involvement before the age of 2 years (Letterer–Siwe disease) is a bad one. Histologic features correlate poorly with outcome. Adults with LCD seem to be at risk for a variety of systemic neoplasms, including lymphomas, leukemias, and lung neoplasms (15). In addition, they may experience secondary macrophage activation syndrome, also known as reactive hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, which is usually fatal. In general, about 10% of patients with multifocal disease die, 30% undergo complete remission, and the remaining 60% embark upon a chronic, shifting course (5).

Histopathology. The histologic picture unites the many varied forms of LCD. The key to diagnosis is identifying the typical LCD cell in the appropriate surroundings. The cell has a distinct folded or lobulated, often kidney-shaped, nucleus. Nucleoli are not prominent, and the slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm is unremarkable. A variety of methods can be used to confirm the identity of such cells. For years the gold standard has been to use electron microscopy to search for the typical Birbeck or Langerhans cell granules. Today, S100 protein, CD1a, and langerin (CD207) can all be identified using paraffin-fixed tissue. Langerin is every bit as specific as Birbeck granules.

Although Lever emphasized three kinds of histologic reactions in LCD—proliferative, granulomatous, and xanthomatous—only the first two are commonly seen. A relationship exists between the type of histologic reaction and the clinical type of disease. The visceral lesions seen in LCD show the same three types of reactions as the skin. In general, the proliferative reaction with its almost pure LC infiltrate is typical of acute disseminated LCD and the granulomatous reaction of chronic focal or multifocal LCD, as the name eosinophilic granuloma suggests. The xanthomatous reaction is seen in Hand–Schüller–Christian disease but primarily in other organs, especially the meninges and bones. Xanthomatous lesions in the skin are decidedly rare.

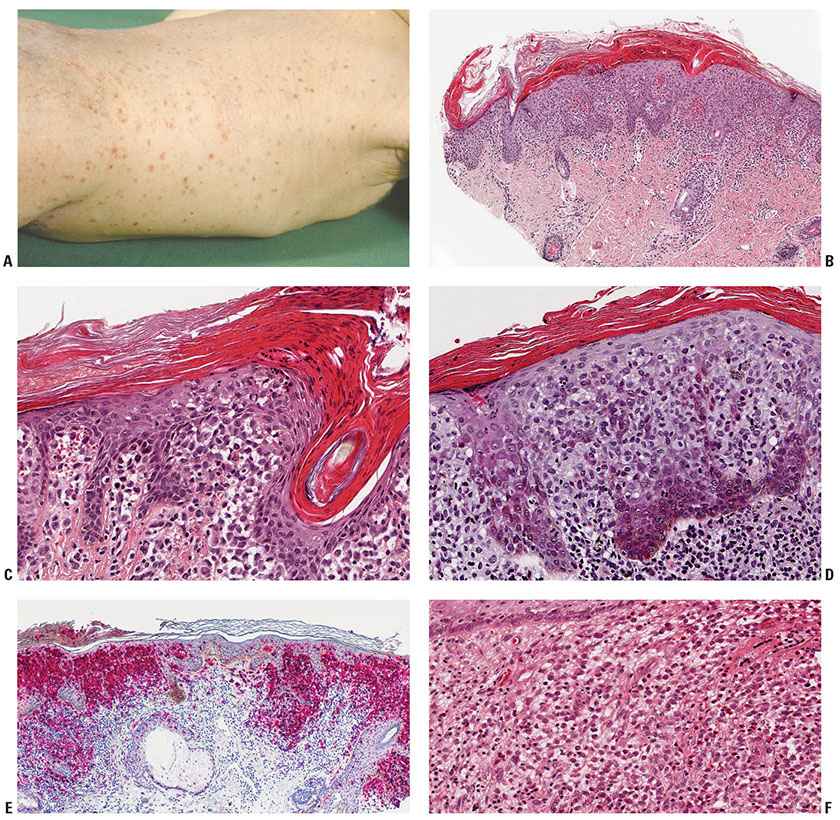

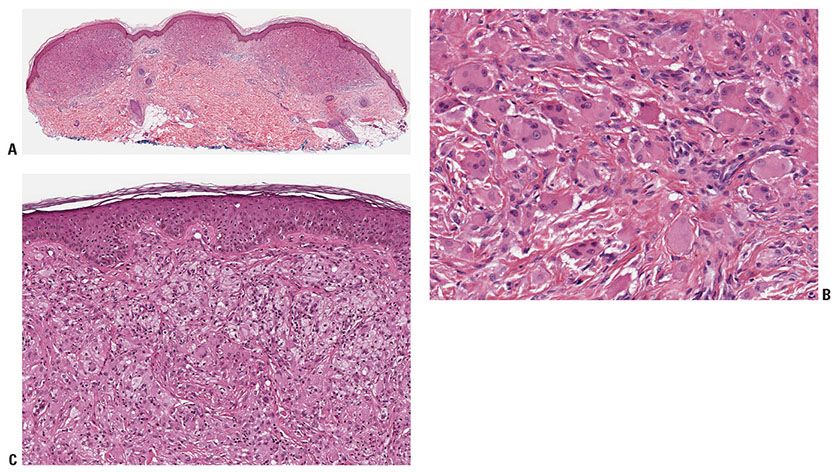

The proliferative reaction is encountered in the skin in petechiae, as well as in almost translucent, hemorrhagic, or crusted papules. It is characterized by the presence of an extensive infiltrate of LC. The infiltrate usually lies close to or involves the epidermis, resulting in ulceration and crusting (Fig. 26-1A). Large, kidney-shaped cells can be seen just below or even impinging on the epidermis (Fig. 26-1B-D). Staining with S100 protein, CD1a, or langerin (Fig. 26-1E) shows both the normal and abnormal LC.

Figure 26-1 Langerhans cell (LC) disease. A: Widespread hemorrhagic papules with scale in an infant. B: Crusted papular lesion in an infant. A dense cellular infiltrate is seen beneath the crust. C: Higher magnification showing accumulations of LCs along the epidermal–dermal junction. D: Another lesion with extensive exocytosis of LC. E: Staining with anti-CD1a and antilangerin identifies both normal epidermal LCs and the tumoral LCs. F: A deep, nodular cutaneous infiltrate rich in eosinophils with clusters of typical large LCs. (A: Courtesy of Wilfried Neuse, Düsseldorf, Germany.)

While CHRSH cannot be definitely separated from other lesions of LCD under the microscope, there are valuable clues. The nodules of CSHRH tend to show densely aggregated LC, often with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 26-1F) and eosinophils.

The granulomatous reaction is found most commonly in infiltrated plaques and nodules in the genital area, in the axillary region, or on the scalp, as well as in the soft tissue and bone lesions. Extensive aggregates of LC often extend deep into the dermis. Eosinophils are present in various quantities (Fig. 26-1F). Generally, they lie in clusters instead of being diffusely scattered and may develop into microabscesses. Irregularly shaped, multinucleated giant cells are occasionally seen. In addition, some neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells may be present. Frequently, extravasation of erythrocytes is found.

The uncommon xanthomatous reaction reveals in the dermis numerous foamy cells, as well as varying numbers of LC and some eosinophils. Multinucleated giant cells are frequently present. They are mainly of the foreign-body type but occasionally have the appearance of Touton giant cells. The S100 protein and CD1a staining is likely to be weak or even negative in the foamy cells.

Malignant Langerhans Cell Disease. Acute disseminated LCD can reasonably be argued to be a malignancy because it is progressive, destructive, and potentially fatal and shows clonality. While some cases have been identified with marked cytological atypia, including mitoses, and a poor clinical outcome, cellular morphology usually is a poor way to predict the course of LCD. The term Langerhans cell sarcoma has been applied to solitary or multiple cutaneous lesions with marked cellular atypia and increased mitotic rate (16,17). On occasion soft tissue and nodal neoplasms have been found that stained only for LCD markers (18).

Pathogenesis. Although LCD has traditionally been defined as a proliferation of LC, there is increasing evidence that other dendritic cells may be involved (19,20). The cells of LCD are not dendritic and they do not migrate. LCD cells have a different gene expression profile than do normal epidermal LC (21). LCD is most often a clonal process. Different groups have studied female patients with the disease and used a variety of X-linked polymorphisms to demonstrate clonality (22,23). Despite these studies, many view LCD as a reactive process because of its tendency toward spontaneous remissions and its good response to mild, nontoxic therapeutic regimens. In a fascinating historical review, Nezelof and Basset, who identified the cell of then “histiocytosis X” as an LC, lamented the fact that discovering this association has provided few clues to what causes the disease (24).

Differential Diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for LCD varies with the histologic pattern. The most difficult situation is an early proliferative dermatitic lesion with little epidermotropism and few characteristic cells. Without adequate clinical background, it is easy to make the mistaken diagnosis of superficial perivascular or lichenoid dermatitis. One should keep LCD in mind in all biopsies of dermatitis from infants and freely employ the S100 protein stain for screening. When a nodule or tumor is present, the presence of eosinophils and the sheets of characteristic cells usually lead to the diagnosis. The cutaneous xanthomas are not distinctive, and whereas the foamy cells may stain weakly with S100 protein or CD1a, usually the surrounding infiltrate has enough positive cells to allow a diagnosis. Some cases of CSHRH may be clinically confused with the blueberry muffin syndrome, congenital leukemic infiltrates, or mast cell disease, but the microscopic picture brings clarity.

Principles of Management. Therapy is often not needed, as LCD has a tendency toward self-resolution. Treatment for purely cutaneous disease should not be aggressive. Solitary lesions can be excised. Topical corticosteroids are the first choice for cutaneous disease; alternatives include topical calcineurin inhibitors and topical nitrogen mustard, as well as systemic methotrexate and thalidomide. All patients with systemic diseases should be considered for study protocols. The standard treatment is vincristine and prednisone, which is better tolerated by children than adults. 6-mercaptopurine appears to be the most effective consolidation and maintenance agent. Bone marrow transplantation is under study. The duration of therapy is 6 months for skin, bone, or lymph node involvement; otherwise 12 months is required.

XANTHOGRANULOMA FAMILY

The xanthogranuloma family is the largest group of cutaneous histiocytic disorders. The source of xanthogranuloma cells is unclear; the two most likely candidates are macrophages and dendritic cells. Macrophages seem most promising based on CD68 staining and their propensity for xanthomatous transformation (25). Another explanation is alternate activation of macrophages, leading to the expression of stabilin 1, a receptor that links exogenous signals to a variety of intracellular vesicular functions. Stabilin 1 can be identified by anti–MS-1 antibodies and seems to be a marker for cutaneous macrophage disorders, as compared to systemic ones (26). We use the term macrophages for the rest of this chapter, fully recognizing that it may be incorrect in some instances.

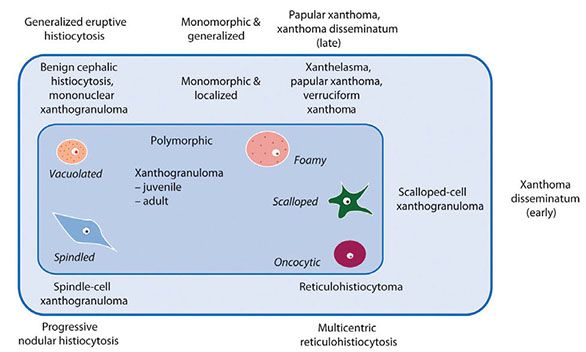

Xanthogranulomas contain cells with a wide variety of morphologic characteristics, including vacuolated, foamy (xanthomatized), spindle-shaped, scalloped, and oncocytic cells (Fig. 26-2). A classic xanthogranuloma contains a mixture of these different cell types, but there are some disorders in which one cell type predominates; these disorders may be further divided into solitary and multiple forms, as the diagram shows (27). Many lesions show two or three patterns, such as a combination of spindled and foamy areas. Incontinence of pigment and uptake by macrophages has been designated xanthosiderohistiocytosis (28) but is not a specific disease, as it can be seen in all chronic forms. The early lesions dominated by nondistinctive vacuolated cells include benign cephalic histiocytosis and generalized eruptive histiocytosis; these tend to regress, as do most juvenile xanthogranulomas in children. All the other lesions tend to be permanent.

Figure 26-2 Unifying concept of the xanthogranuloma family.

Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

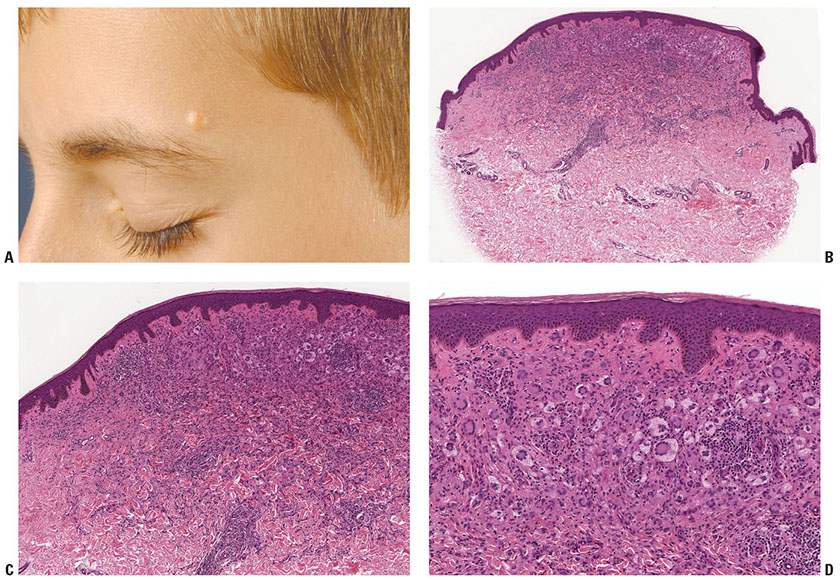

Clinical Summary. Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) is a benign disorder in which one, several, or occasionally numerous red-to-yellow papules to nodules are present (Fig. 26-3A). Because the lesions are also seen in adults, JXG is admittedly an imperfect term. Because we have used xanthogranuloma to describe a type of lesion and family of disorders, we prefer to retain the designation JXG for these specific lesions.

Figure 26-3 Juvenile xanthogranuloma. A: Yellow-brown nodule in a typical facial location in a child. B: Elevated nodule with epidermal collarette. At scanning magnification, giant cells already can be identified. C: Infiltrate rich in Touton giant cells; also note entrapment of collagen at periphery, just as seen in dermatofibroma. D: Numerous Touton giant cells at higher magnification; cytoplasm within the wreath of macrophages is slightly more eosinophilic than that at the periphery. (A: Courtesy of Wilfried Neuse, Düsseldorf, Germany.)

The papules and nodules are usually 0.5 to 1.0 cm in diameter. Most lesions appear during the first year of life; 20% are present at birth. In children the lesions may grow rapidly but almost always regress within a year. Lesions in adults are not uncommon but are usually solitary and persistent. JXG may be clinically subdivided into several forms. The micronodular variant is most common; patients are infants with many papules and small nodules. Occasionally a macronodular form is seen with only a few lesions, but these are often several centimeters in diameter. The solitary giant xanthogranuloma may be larger than 5 cm (29). Lichenoid papules (30), large plaques (31) or even destructive lesions such as with nasal involvement (the Cyrano sign) may be seen (32). There are also subcutaneous or deep JXG (33). As discussed above, JXG may develop in patients with LCD; this may represent a xanthogranulomatous response to the inflammation of LCD.

A number of systemic complications are associated with JXG. Ocular involvement, including glaucoma and bleeding into the anterior chamber, is the most common; it occurs in less than 10% of young patients (34). Oral lesions may occur. An association between JXG, café-au-lait macules, neurofibromatosis I, and juvenile chronic myelogenous leukemia has been reported but must be rare (35). JXG has also been identified in many other organ systems, including the central nervous system, kidney, lungs, liver, testes, and pericardium.

In two large series, involving more than 300 patients in pediatric pathology referral centers, 5% of the patients had widespread systemic disease (36,37). These patients are at risk for infections and macrophage activation syndrome, and some may die. Although some of these children present with cutaneous disease (38), most do not. It is neither necessary nor wise to raise the specter of systemic involvement each time an infant or a child is seen with a solitary cutaneous JXG. Xanthogranulomas have also been associated with hematologic malignancies in adults (39) and following ionizing radiation (40). Adults with xanthogranulomas and systemic problems may have Erdheim–Chester disease, as discussed below.

Histopathology. The typical JXG contains macrophages with a variety of cellular features. On low power, a well-circumscribed nodule, often exophytic and with an epidermal collarette, is found (Fig. 26-3B). Typically many of the stylized morphologic variants of macrophages can be seen. There is usually a characteristic progression as the lesions mature. Early lesions may show large accumulations of vacuolated cells without significant lipid infiltration intermingled with only a few lymphocytes and eosinophils (Fig. 26-3C). When no foamy cells or giant cells are seen, the possibility of JXG is often overlooked (41). This mononuclear variant of JXG is identical to lesions found in benign cephalic histiocytosis and generalized eruptive histiocytosis.

Usually some degree of fat uptake is present, even in very early lesions, as manifested by pale cells. In mature lesions, a granulomatous infiltrate is usually present containing foamy cells, foreign-body giant cells, and Touton giant cells, as well as lymphocytes, and eosinophils. The presence of giant cells, most of them Touton giant cells, showing a wreath of nuclei surrounded by foamy cytoplasm is quite typical for JXG (Fig. 26-3D) but not diagnostic because wreath-shaped giant cells can be seen in other disorders, including some melanocytic nevi. Occasionally, Touton giant cells are absent even in mature lesions. Older, regressing lesions show fibrosis replacing part of the infiltrate. Occasional lesions are mitotically active, but this is not clinically significant (42); as expected, the mitoses are seen in nonfoamy cells, as these are terminally differentiated and do not divide.

Pathogenesis. The cause of JXG is unknown. The cell of origin is controversial, as discussed previously.

Differential Diagnosis. The clinical differential diagnosis includes Spitz nevi, mastocytomas, and dermatofibromas. The typical histologic picture of JXG is unmistakable. The many variants lead to a baffling array of diagnostic possibilities, which are considered under the individual variants.

Principles of Management. Most lesions in children regress spontaneously; those in adults do not. Solitary or few lesions can be excised; reexcision is not needed if the margins are involved.

Papular Xanthoma

Clinical Summary. Papular xanthomas (PX) are small flesh-colored or yellow to red-brown papules. Patients present with one, several, or many papules (43). Although the lesions may be generalized, they have neither the distribution pattern of xanthoma disseminatum (XD) nor the confluence of diffuse normolipemic plane xanthoma (DNPX). Plaques are not seen. The patients show no abnormalities of lipid metabolism. Most patients are adults, but occasional cases have been seen in children. The oral mucosa may be involved. PXs are one of the two characteristic lesions of progressive nodular histiocytosis.

Histopathology. Nodules containing foamy cells with numerous Touton giant cells are seen in the dermis. Extracellular lipids are not seen. Even when early lesions are biopsied, foamy cells predominate, with only a small component of mononuclear vacuolated macrophages or other cell types (Fig. 26-4A, B).

Figure 26-4 Papular xanthoma. A: Pale papule without epidermal reaction or clefting. B: Numerous foamy macrophages with typical granular cytoplasm. Extracellular lipids are not present.

Pathogenesis. Why some macrophages become foamy in the presence of normal serum lipid levels is not known. Despite the early definition of papular xanthoma as a macrophage disorder without a macrophage precursor phase, there must be macrophages present initially that rapidly take lipids. PXs with neutrophils have been described in normolipemic patients with HIV/AIDS (44).

Differential Diagnosis. Papules made up of predominately foamy cells may also be associated with elevated lipid levels or be a paraneoplastic marker, as in DNPX. Solitary lesions may be mistaken clinically for dermatofibroma, Spitz nevus, and a variety of other benign proliferations.

Principles of Management. Solitary or few lesions can be excised.

Scalloped Cell Xanthogranuloma

Clinical Summary. Scalloped cell xanthogranuloma is not clinically distinct. We identified a number of lesions in which the predominant macrophage is scalloped, once we had become aware of this morphologic variant in XD and began searching for solitary lesions to fill in our unifying concept scheme (45). The lesions are typically on the head, neck, or back of young men and may be diagnosed as juvenile xanthogranuloma or, less often, melanocytic nevus or basal cell carcinoma.

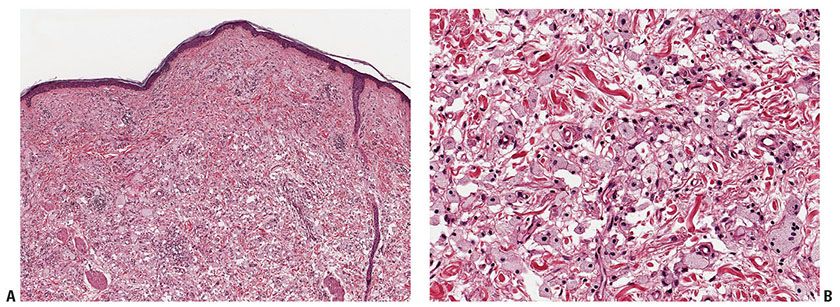

Histopathology. While scalloped macrophages predominate (Fig. 26-5B), a mélange of other macrophage types may be found.

Figure 26-5 Xanthoma disseminatum. A: Early lesion with rather monomorphic infiltrates. B: Higher magnification, showing scalloped and oncocytic cells. C: Later lesion showing foam cells as well as occasional Touton giant cells.

Principles of Management. Solitary or few lesions can be excised.

Xanthoma Disseminatum

Clinical Summary. XD is a rare but distinctive disorder featuring numerous widely disseminated but often closely set and even coalescing, round to oval, orange or yellow-brown papules, and nodules (46,47). Lesions are found mainly on the flexor surfaces, such as the neck, axillae, antecubital fossae, groin, and perianal region. Peculiar target lesions may be seen. Often there are lesions around the eyes. The mucous membranes are affected in 40% to 60% of cases. In addition to oral lesions, there may be pharyngeal and laryngeal involvement. Three patterns have been identified; the most typical is the persistent form. Rarely, lesions may regress spontaneously, and even more infrequently in the progressive form there may be significant internal organ involvement. The largest review (46) suggests that most cases begin in childhood, where the diagnosis can be problematic, as, for example, in an infant with mucosal and pituitary lesions. We have only seen the disease in adults.

Diabetes insipidus is encountered in about 40% of cases but usually is less severe than that associated with LCD. Characteristically, internal lesions other than diabetes insipidus are absent. In a few instances multiple osteolytic lesions have been found, especially in the long bones, as well as lung and central nervous system infiltrates.

Histopathology. In early lesions, scalloped macrophages dominate the histologic picture, with few foamy cells (Fig. 26-5A, B). Most well-developed lesions contain a mixture of scalloped cells, foamy cells, and inflammatory cells, as well as Touton and foreign-body giant cells (Fig. 26-5C) (48) Another rare feature is hemosiderin-laden macrophages in the upper dermis, also known as xanthosiderohistiocytosis (28).

Pathogenesis. Although in both XD and LCD xanthomatous lesions and diabetes insipidus may occur, the two should not be confused. XD occurs in older patients, often has mucosal involvement, and only rarely involves bone. Finally, xanthomatous lesions are expected in XD and rare in LCD.

Principles of Management. There is no effective treatment. A variety of cytostatic agents are usually employed but the disease usually progresses.

Reticulohistiocytoma and Multicentric Reticulohistiocytosis

We divide what has traditionally been called reticulohistiocytosis into giant cell reticulohistiocytoma (GCRH) and multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH). Both disorders occur almost exclusively in adults. The histologic picture is very similar in the two types, but everything else is different.

Clinical Summary. GCRH is simply a xanthogranuloma in which the oncocytic macrophages and giant cells predominate. It is never clinically unique but diagnosed as a JXG or dermatofibroma. The clinical features, distribution, and course are identical to those of JXG. In greater than 90% of cases, the lesion is single, but occasionally multiple lesions are seen (49). Even patients with multiple lesions show no sign of systemic involvement.

In multicentric reticulohistiocytosis, a name first coined by Goltz and Laymon (50), the patients tend to be females, usually in the fifth or sixth decade of life, with widespread cutaneous involvement and a destructive arthritis (51–53). Nodules ranging in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters are most common on the extremities. Multiple papules on the face may coalesce, producing a leonine facies. Many small papules along the nail fold create the “coral bead sign.” In about half of the patients, nodules are present also on the oral or nasal mucosa. Finally, about 25% also have xanthelasmas.

The polyarthritis may be mild or severe but is almost always present. It may be mutilating, especially on the hands, through destruction of articular cartilage and subarticular bone. Some patients present with features mimicking dermatomyositis (54

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree