THE FEMININE SKIN AS ANXIOUS ARCHIPELAGO

4

Skin is the textile of time and writing. It is the first and enduring medium with which we encounter the world, and skin comes to metaphorically embody the relationship between our interior and exterior lives. The fabric of our skin is able to accomplish a feat that nothing else in our lives is able to, no matter how fervently we may wish – it can turn time backwards. An opening up of the body through blade or fire seals itself, restoring the skin’s integrity through a stunning process of scarring and reparation. Steven Connor astutely observes that cosmetic surgery attempts to replicate the magical properties of skin to coax time into dissolution.1 He offers many metaphorical alternatives to thinking about the skin as a screen or a slate, but his suggestion that the skin can be thought of as an archipelago is a particularly touching metaphor for the skin in cosmetic surgery. In cosmetic surgery, skin is a psychic and somatic archipelago of meaning, experience, and memory, dispersed across a social and cultural sea. As a cartographer of skin in cosmetic surgery, I must persistently attend to this landscape of skin to resist collapsing it into a flat, static surface.

Skin is the earliest interface through which we encounter otherness. This otherness is experienced tactilely, and we continue to experience the self and other as separated by our skins. The skin is racialized, gendered, and sexualized through its reading by others, which marks a shift from the tactility of early infantile experience to the visual experience that predominates our contemporary understandings of skin. Focusing on the skin as cosmetic surgery’s de-idealized surface, I elaborate on the psychic promises and difficulties of conceiving one’s body according to the terms of surface imaginations. The skin is a troubled surface in contrast to the photograph; it is miraculous in a different way, yet recalcitrant. The restorative and inscriptive capacities of skin sustain the central surface imagination fantasy of cosmetic surgery, which is that we can consider our bodies as infinitely alterable and customizable according to our wishes. An intervention into the skin through cosmetic surgery is a means of asserting agency over the body with the hope of alleviating suffering, although this agency is always partial: the body itself is contingent and may not respond to our interventions.

A psychoanalytic understanding of skin situates the skin’s importance to cosmetic surgery, providing a foundation for my analysis of the skin as a de-idealized surface in the interview narratives. I begin with Freud’s theory of the bodily ego, which considers how the experiences of the body (and in particular the experiences of otherness) structure the psychic apparatus; this is key to interpreting the way surface imaginations conceptualize the skin. Freud posits that the ego cannot be thought of as a surface, but rather as a projection of a surface. This insight is the inspiration for Didier Anzieu’s metaphor of the skin ego. The interview narratives trouble and complicate these concepts of the bodily and skin egos through their emphasis on contingency, the relation between the interior and exterior of our bodies, and time.

In contrast to the idealized surface of the photograph, the de-idealized surface of the skin challenges the fantasy that the body can be altered according to our desires in three overlapping ways. First, the skin is a site through which we experience and learn contingency and accident,2 and thus cosmetic surgery can be thought of as a way of asserting control over the contingent skin. However, having cosmetic surgery also throws the patient into a confrontation with the contingency of skin, for it is impossible to absolutely predict the results of a surgery. Here I explore how participants discussed the unknown and accidental qualities of their skin. Second, skin is an allegory of time, and time is marked upon our bodies. These marks may appear suddenly and temporarily, as in the bruise or laceration, or they may happen gradually and permanently, as in the wrinkle or scar. Here I am concerned with skin transformations and the delineations of time, and I argue that cosmetic surgery facilitates the assumption of a second skin3 for the patient. And, finally, the skin is a metaphor and locus for the exchange and connection between our interior psychic lives and our exterior social world. The complaint that one does not feel on the inside the same way that one appears to the outside frequently precipitates a decision to have cosmetic surgery. This complaint, often described as feeling as though one is in the “wrong body,” marks an interesting parallel and divergence between “cosmetic” and “sex reassignment” surgeries, and toward the end of the chapter I offer a speculative consideration of this (dis)connection. In conclusion, I consider how the skin is a site where the interior and exterior worlds collide and negotiations between the individual and the cultural occur.

The Bodily Ego and the Unconscious

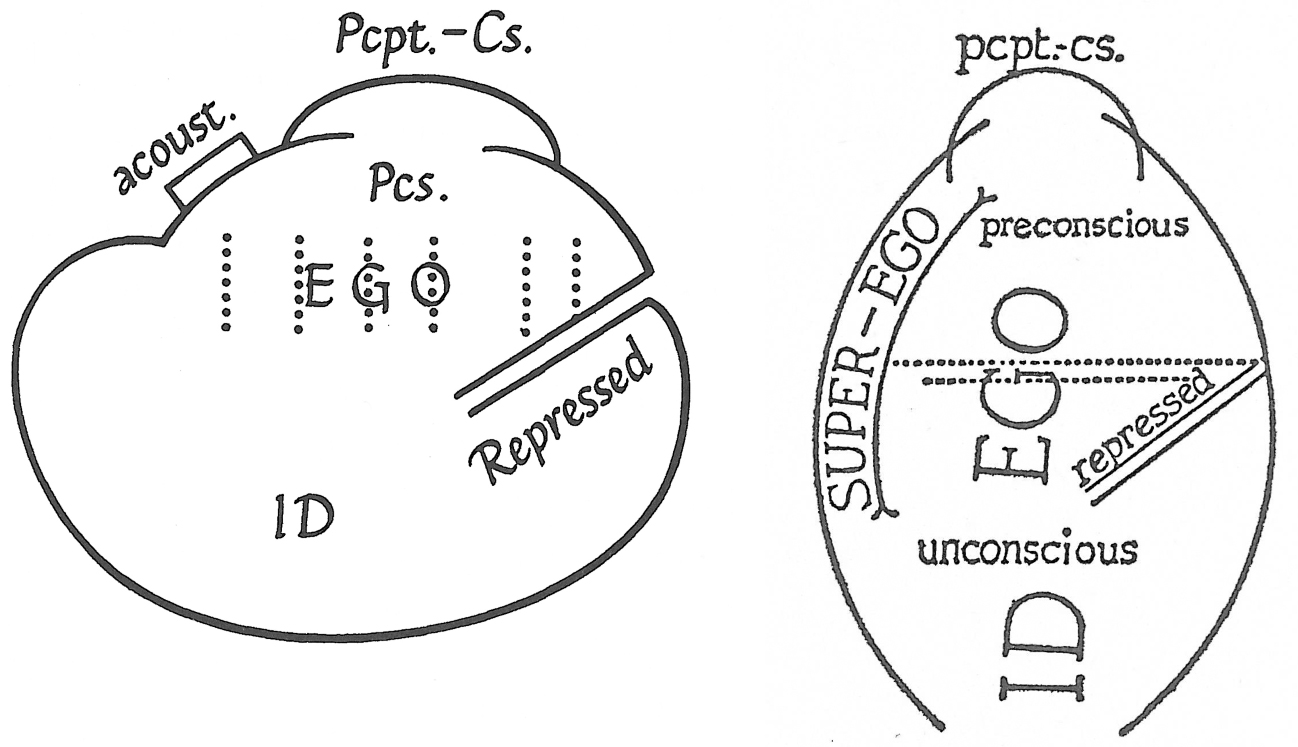

4.1 and 4.2 Two of Sigmund Freud’s structural diagrams of the mental apparatus reprinted from “The Ego and the Id” (1923) and “The Dissection of the Psychical Personality” (1933)

Before I discuss Didier Anzieu’s lovely metaphor of the skin ego, I want to first trace my path back to Freud’s skin-sheathed theories of the unconscious, consciousness, and the ego. In “The Ego and the Id” (1923) Freud explains that the role of the ego is to act as a mediating space between the unconscious (id) and the preconscious-conscious (perception-consciousness system and the external world), and describes the ego as a “frontier-creature”4 and “a poor creature owing service to three masters and consequently menaced by three dangers: from the external world, from the libido of the id, and from the severity of the superego.”5 The ego’s wish is to impress upon the id the demands of the external world, or to assert the dominance of the reality principle over the id’s insistent adherence to the pleasure principle and the death drive.

Freud’s theory is astonishing in its affirmation that our body is a site of internal and external perceptions and the locus of mental processes, which stands in contrast to the Cartesian privileging of the mind over the body. According to Freud, the manner in which we perceive unconscious mental processes with our consciousness parallels our perception of the external world with our sense organs.6 He says that the unconscious is timeless, but consciousness, like skin, bears the burden of time.7 When we touch ourselves, we see our bodies as we would see any other object, but the reflexivity of the touch relationship gives us an idea of the experience of a location that perceives from the inside and the outside (like the ego): “A person’s own body, and above all its surface, is a place from which both external and internal perceptions may spring. It is seen like any other object, but to the touch it yields two kinds of sensations, one of which might be equivalent to an internal perception.”8 In this way the body is the foundation of our psychical lives, and in particular the skin occupies the ambiguous condition of being a reciprocal organ that feels from the inside and out and, further, can touch itself. When Freud says, “the ego is first and foremost a bodily ego,”9 he means that the body is inseparable from the mental apparatus and they act as templates of experience for each other. Unlike consciousness (the surface of our mental apparatus), the ego is “not merely a surface entity, but is itself the projection of a surface”10 because it projects the conscious world to the unconscious and back again in its mediating function. Similarly, the skin is more than surface in its vast communicative capacities between the interior and exterior of the body and between the conscious and unconscious, navigating through a vast topography of embodied thought and feeling.

Freud’s description of the ego as a projection of surface evokes both the idealized and de-idealized surfaces of cosmetic surgery. The word “projection” can refer to visual technologies that transmit an image onto a flat surface (for example, a slide projector), or it can refer to the psychoanalytic concept of how qualities of one’s self are externalized and perceived as qualities of others (both positive and negative). Projecting an image is a literal and figurative action within the surface imaginations of cosmetic surgery; the patient wants to project a more positive or accurate image of herself to the world, and the patient and surgeon rely on the projection of photographic images in order to envision the results of surgery. The negative qualities of the skin are projected outward onto others, who are truly old, fat, or ugly, unlike the patient who is unjustly afflicted by the appearance of being so. The psychical action of cosmetic surgery happens at the level of the ego and the image, and because Freud developed his theory at the historical moment when surface imagination logic emerges, this convergence of the ego, photography, and skin as mediator is no accident.

In a rather peculiar little essay that appears chronologically later than “The Unconscious” and “The Ego and the Id,” Freud elaborates his theory of the perceptual system. “A Note upon the Mystic Writing-Pad” (1925) brings Freud’s theory of mind into close contact with the skin’s surface as a consequence of his selecting the mystic writing-pad as a metaphor to explain perception. The mystic writing-pad is a children’s writing toy that has three layers: the top layer is made of strong, transparent celluloid; the middle layer is made of a translucent waxed paper that is fragile and sticks lightly to the bottom layer, composed of brown wax. When you write on the top layer with a stylus as you would write on a piece of paper with a pencil, the middle layer is impressed by the stylus into the bottom wax layer, and the writing appears. Once you decide you would like a fresh writing surface, you simply lift up the top and middle layers to unstick the writingimpressions from the wax. Your writing surface is now clear, and a slight imprint of the writing is left in the wax layer. Like a sheet of paper, the mystic writing-pad is capable of maintaining permanent traces, but it does not have to be replaced once it is full of writing; like the chalkboard, it can be reused endlessly, but without the drawback of losing the traces of writing every time you erase the board to write anew. While the devices that we use to amplify our senses emulate the sense they are to enhance (Freud gives the examples of “spectacles, photographic cameras, ear-trumpets”), he comments that “devices to aid our memory seem particularly imperfect, since our mental apparatus accomplishes precisely what they cannot: it has an unlimited receptive capacity for new perceptions and nevertheless lays down permanent – even though not unalterable – memory-traces of them.”11 Together, the top and middle layers of the mystic writing-pad perform the same function as the perception-consciousness system, taking in traces from the external world but also protecting its own fragility, and the wax layer beneath is analogous to the unconscious, which retains all the traces filtered through the perception-consciousness system.

As Anzieu has noted, “A Note upon the Mystic Writing-Pad” presages later anatomical descriptions of the skin as a membrane composed primarily of two layers that protect the interior of the body: the epidermis and the dermis.12 The strong, resilient epidermis consists of five layers of predominantly dead, but also developing, cells, and functions as a protective shield to the more vulnerable dermis, which contains blood vessels, nerve endings, sweat glands, hair follicles, and connective tissue, and the subcutis, which is a layer of fatty tissue.13 The aptness of Freud’s claim that the ego emerges from our embodied experience is reflected in his idea that our perception-consciousness system functions like a skin. This claim is also foundational to contemporary understandings of surface as revealing of interior workings and thus of primary significance, and yet this surface of perception-consciousness is also layered, like the skin. It is perplexing that Freud himself does not use the metaphor of skin to develop his discussion of the relationship between perception, consciousness, and the unconscious. However, Didier Anzieu, in his career as a psychoanalyst working in the field of dermatology, formulated his own metaphor of the skin ego, which clarifies and extends Freud’s concept of the bodily ego.

The Skin Ego

The skin ego is a metaphor that swans over the boundary between British/American and French psychoanalytic schools of thought, and represents this border as porous, rather like its eponymous organ. Anzieu characterizes the division as, on the one side, British/American psychoanalytic theory’s empirical approach, which focuses on object-relations and psychogenesis through unconscious happenings in childhood, and, on the other, French psychoanalytic theory’s structural approach, which focuses on psychical structures at the expense of an acknowledgment of the importance of experience in shaping structure.14 It should also be noted that Anzieu is specifically theorizing contra Lacanian psychoanalytic theory and its linguistic turn, which he considers overly grounded in philosophy, the humanities, and social science, at the expense of clinical practice.

Since he privileges imagery and clinical experience over what he characterizes as abstract and formalistic theorizing,15 Anzieu describes the skin ego as a metaphor rather than a fully fleshed-out concept. The skin ego metaphor should be understood in the context of twentieth-century European history which, according to Anzieu, is an epoch typified by a “need to set limits.”16 He observes that over the duration of his practice as a psychoanalyst, the features of his patients’ anguish have changed from occupying the territories of Freud’s neuroses to occupying borderline (between neuroses and psychoses) and narcissistic states. These states occur more frequently due to a greater cultural need to set limits and boundaries.17 Linking his metaphor of the skin ego to research in mathematics, astronomy, and biology, which, Anzieu notes, has a preference for taking the interface or membrane as its subject over the infinite and limitless, he delineates his project as the theorization of how psychical envelopes are formed, structured, made pathological, and restored.18 Anzieu’s metaphor of the skin ego is described in two significant passages:

By Skin Ego, I mean a mental image of which the Ego of the child makes use during the early phases of its development to represent itself as an Ego containing psychical contents, on the basis of its experience of the surface of the body.19

From [its] epidermal and proprioceptive origin, the Ego inherits the dual possibility of establishing barriers (which become mechanisms of psychical defence) and filtering exchanges (with the Id, the Super-Ego and the outside world).20

The skin ego exists in the realm of phantasy;21 like all psychical activity, it is reliant upon a biological foundation (in this case, the skin).22 Skin is our original communicative interface with the world: “The original form of communication but in reality, and more intensely, in phantasy, is direct, unmediated, from skin to skin.”23 This deep connection between our biological and psychical lives establishes the foundation of sensory experience. According to Anzieu, this “structural primacy” occurs because the skin is an organ that envelops the entire body and also because it is the medium through which we first communicate with the exterior world; therefore, we relate each of our senses to this fundamental sensory experience.24 To be more precise, the sensory pre-eminence of skin is important not just as a foundation of the senses, but also as a foundation for the reflexivity of our senses.25 Anzieu elaborates on Freud’s discussion of touch as reflexive and the child’s experimentation with touching as unique in that the child can apprehend being a touching skin and a touched skin at the same moment.26 Touching one’s self is the precondition of being able to hear one’s self talk, see one’s self gaze in the mirror, and smell one’s own scent (the examples offered by Anzieu).27 Anzieu traces this discussion about the reflexivity of skin back to Freud’s statement in “The Ego and the Id” that the body’s surface produces the doubled effect of internal and external sensitivity:28 as such, the skin is a surface that is both reflexive and doubly perceptive from the interior and exterior. From this reflexivity Anzieu infers that the skin ego consists of two layers, like the epidermis and dermis or the celluloid and waxed paper of the mystic writing-pad, “one turned towards exogenous stimulation, the other towards internal instinctual excitations.”29 While this conclusion connects most obviously to the skin’s mediation of the interior and exterior world in cosmetic surgery narratives (as this mediation is reflexive), it also indirectly connects to the contingency of the touch.

The passages that describe Anzieu’s skin ego highlight two main characteristics of the metaphor: the skin ego holds the contents of the psyche, and the skin-origin of the ego leads the ego toward its functions as barrier and filter. The skin ego parallels the biological skin’s unique abilities to literally hold us together but, unlike an ordinary container, which is rigid, the skin (ego) simultaneously mediates exchange between the interior and exterior of our bodies. As in Freud’s discussion of the relationship between consciousness, the ego, and the id, according to Anzieu, the skin ego acts as an intermediary between the inside and the outside: the self distinguishes the psychical ego as its own, and separates this psychical ego from the bodily ego, which is prone to seductive and persecutory influence.30 What separates the psyche from the body, and in so doing dissolves this separation, is the skin ego: an entity that cannot function without the integration of both. The psychical ego supports a narrative of one’s self as a coherent and rational being, and the ego’s separation of psychical from bodily ego represents a desire to shunt off the uncontrollable and real effects of the body. The cosmetic surgery patient might seek surgery as a means to counter this uncontrollability, but in so doing is thrown into confrontation with the contingent nature of the body (since surgical results are entirely unpredictable).

The skin ego relies anaclitically on the functions of the skin to determine its own topography: holding the psychical contents together as if a container or sac, acting as an interface between the interior and exterior, and as a communicative surface that can also bear inscription.31 One of the skin ego’s functions is the offering of a “narcissistic envelope” that gives us the fundamental psychical sense of safety that we require in order to interrelate with the world,32 a response to the differentiation within the ego. Feeling that we belong in our skins, and that our skins belong to us, is tantamount to feeling emotionally and physically protected. This envelope is narcissistic and non-perverse because it requires taking one’s own skin/self as loved object in the interests of self-preservation and self regard.33 The skin ego emerges because the child’s experiences of the world are mediated by its body and particularly by its skin (breastfeeding is an exemplar of skin to skin/world contact), and the child thinks about its psyche as contents that are encased within a skin. Likewise, cosmetic surgery tests the skin ego by reaffirming the skin’s remarkable capabilities to self-repair, thus mirroring one’s psychical ability to hold the self together. The testing of the skin points to the metaphor, in cosmetic surgery, of the skin as a soft clock on which the passage of time is recorded and from which it is effaced, and the boundary of the interior and exterior is rigidified into a fantasized exteriority.

The biological skin is capable of bearing the marks of the exterior world and of others’ significations. From the skin’s function as a storytelling surface, Anzieu proposes that the skin ego is the foundation and inspiration of thought,34 and likewise that writing and speech can function like a skin.35 The poignant affiliation between the skin (ego) and thought is particularly salient in the case of cosmetic surgery, where the cosmetic surgical intervention can be conceptualized as a type of inscription upon the surface of the skin. This inscription may be evident only to the patient, but if we take up seriously this intimate connection between skin and thought, cosmetic surgery is a way of thinking through the skin. When a part of the body becomes a locus of dissatisfaction due to its nonconformance with the self’s reading of what the body ought to look like, to declare this a case of bad body image or to claim that this reading is mistaken or overblown is to dishonour and trivialize that dissatisfaction. Or, rather than adopting a definition of “body image” that is common to feminist critique (where body image is understood as an incorrect assessment of one’s body influenced by advertising and the media), we can take seriously Paul Schilder’s definition of body image as an imagined, yet very real experience. The latter definition is more productive in my considerations of cosmetic surgery because it does not dismiss the fleshiness of our body-thoughts and offers us a framework from which to understand how an intervention into the body can be a productive way to work though psychical dissatisfaction. Further, to understand a dissatisfaction with the body as primarily socially influenced misses the point that the skin is a container, interface, and inscriptive surface for the psychical dissatisfaction and that this dissatisfaction is transposed onto the skin as the bearer of thought and meaning. In this way we can say that the practice of cosmetic surgery transpires on and underneath the skin, and is a thought-negotiation of the boundaries of the skin ego within the consideration of standards of femininity and beauty. These intentional marks of cosmetic surgery are in response and opposition to the unintentional mark of the body, and are a way of negotiating accident, time, and boundaries. Through this line of thought we can see that surface imaginations are not trivial, but central to how identity is formed and lived through the surface of the body.

Contingency

Particularly troubling about the contingent qualities of skin is the fact that the chain of events that leads to a particular manifestation of the skin can be internal or external (or indeed, often confounds the boundary); thus, there is no possibility for protection. Contingency writes itself upon the skin by accident, marking the passage of time and life events in a way that is uncontrollable. The pre-surgical skin is experienced as a contingent organ in cosmetic surgery narratives. What happens to the skin seems to occur by happenstance or accident, or seems dependent on unknown conditions of the future, present, or past. In many of the interview narratives, cosmetic surgery is a way of navigating this contingency, and holds out the promise that surgery can manage the anxiety that arises from the skin’s contingency. However, as the interviews demonstrate, cosmetic surgery can only ever partially fulfill this surface imagination-infused promise: the patient and surgeon are unable to assert total control over the cosmetic surgery procedure, for the results are unpredictable. This is a fundamental challenge to the promise made by the surface imagination logic of the photograph, which effects transformation easily and without contingency. In stark contrast to the photographic surface, the skin’s surface possesses a frustrating accidental quality as it forms wrinkles, stretch marks, and scars, making it a de-idealized site in the practice of cosmetic surgery.

The Gravity of Age (Tigerlily, lower face, neck, and eye lift)

As you age,

Strange things

happen

to your features.

That really bothered me a lot; every decade another thing.

When my neck started going,

I was sixty.

I remember being very surprised

Because my parents didn’t have as much of a turkey neck.

The gravity had set in.

I had this

downward

pull

to

my

face.

I looked miserable, unhappy, cross or sour.

Which did not reflect how I felt in the least.

Thinking about the skin as an object in cosmetic surgery collapses the distinction between the cutis, or the skin that is alive, protective, and receptive, and the pellis, the skin that is lifeless and subject to textile treatment such as tanning, cutting, and sewing.36 Connor says that the marking of the skin instantiates the renunciation of skin as a part of the living creature and the objectification of skin into a two-dimensional pellis.37 Cosmetic surgery is always a marking of skin, even in its most non-invasive forms. The mark that cosmetic surgery leaves on the body commemorates the moment that the cutis folded into a pellis. This figurative death engenders a rebirth of the skin into a condition that manages anxiety through a negation of the contingency of the skin’s marks. When I interviewed Tigerlily, she described the contingent and “strange” marks of her skin as a “deterioration or when gravity sets in.” The transformation of Tigerlily’s skin is not within her control and is instead the result of a gravitational or otherwise mysterious force. Tigerlily described herself as still “energetic,” which was in stark contrast to the adjectives that she used to describe her face, such as “miserable,” “sour,” “cross,” and “hideous” because of what she called her “turkey neck” and hooded eyes. She “wanted to reflect to the outside world more of how [she] felt,” and in describing her face and neck as parts of a turkey and cloaked in an obscuring skin, she marked these parts as separate from her authentic, interior self. The objectification of her face and neck facilitated an intervention at the level of skin that Tigerlily described as “repulsive” and “frightening” due to the opening up of the skin and unknowability of the results. We can think of this as a response to the objectifying and anxiety-ridden folding together of cutis and pellis and the accidental quality of all revisions to the skin, even the ones we may choose.

The post-surgical skin has undergone a transformation that writes the skin’s vulnerability onto its surface in the form of a bruise, a hole, or a scar. The mark of the surgical intervention corresponds to another of Connor’s insights: since one’s skin is an object of time, it can only be revised,38 because the skin’s markings are sites through which we experience contingency and law.39 The skin’s marks are frequently experienced as arbitrary and senseless because they do not emerge from our conscious will, as Tigerlily’s story attests. Cosmetic surgery is a surface imagination technique for managing the contingency of the skin and the anxieties that arise from its display. Most often, others visually apprehend our skins before they embrace them by the other senses, and we think of the skin as revealing our interiors regardless of our wishes. Tigerlily’s story, with her discussion of the effects of lighting and makeup that helped to more accurately reflect her inner self, which was neither “cross” nor “sour,” presents this view of the skin. In a peculiar paradox, however, we also strongly adhere to a notion that our skins fail to reveal the entirety of our being: a common saying is that beauty is only skin deep, for example. Cosmetic surgery is a means to conceal time’s contingent writing upon the skin,40 and is a distancing of one’s self from accident, decay, and death.

Skin is remarkably vulnerable and yet often an opaque obstacle between the self and the world. The vulnerable obstacle of skin is a site of shame, since it fails to consistently conceal or disclose the interior life and is thus persistently misread culturally.41 Leah identified stretch marks on her breasts as “the most significant reason” for deciding to obtain a breast reduction and lift. This reason seems incongruous with other more commonsensical reasons for getting a breast reduction, such as back and neck pain, considering large or pendulous breasts aesthetically unappealing, or being fed up with unwanted public hypersexualized and fetishized attention. In fact, having a breast reduction will not do anything about stretch marks, which is something Leah was fully aware of when she went into surgery. She asked her doctor if the reduction surgery would help conceal the stretch marks, and if not, could he “throw some skin on top of there?” The hope expressed in this request is that the surgeon can perform the same alchemy that the photographer can by adding a layer (or filter) over top of the flawed skin to airbrush its contingency.

Leah discussed at length the use of clothing to conceal her stretch marks throughout her history of possessing breasts: “throwing some skin on top of there” would hide the marks in a way analogous to clothing. She did not “need” her breasts because she had no “use” for them. Leah said, “I wasn’t worried about [them being] too small, because I was sort of like, honestly, you can take them all, I’m not attached.” Like Tigerlily, Leah separated the marks on her breasts from her self as “not-her” due to their accidental quality, conceiving of the self as intentional. Leah described the use of large breasts as purely exhibitory: since she did not show them off, it was unnecessary for her to have them. Since she expressed feeling shame and embarrassment regarding her breasts, the stretch marks operate as a synecdoche for the shame of coming to occupy a highly charged symbol of femininity. Leah’s attachment to her breasts was filled with ambivalence about femininity: “I wanted to have the surgery [to] get rid of them a little bit, because I really don’t need them for anything … but I still want to, like I’m still a woman [and] I still want to be feminine and I still want to you know, have breasts but I just don’t need the full package.” Stretch marks are a contingent mark on the skin that remember a time of great physical transformation, and the “full package” of femininity is one of showy surface exhibition (of breasts in particular).

Surprisingly, even though Leah’s breast reduction surgery left large and noticeable scars on her breasts, she was completely comfortable with these scars. According to analyst Barrie M. Biven, feeling shame and embarrassment upon one’s skin is a strain on one’s sense of self-cohesion, and this is often expressed as a desire to escape from, cut, or mutilate the skin as a way to re-establish boundaries and self-cohesion.42 Often fantasy is a sufficient way of coping with this strain, and Biven explores the everyday projection of one’s skin onto living and inanimate objects as a way of negotiating bodily boundaries. The painter’s relationship to the canvas is one example of such a projection. The contingently marked and injured skin causes psychic distress not because it represents a biological threat to the organism, but because it disturbs the integrative psychical function of the skin. Connor says that the powerful libidinization of the skin cannot be separated out from a desire for integration through the skin.43 Given that Leah’s happenstance stretch marks concerned her a great deal, while the deliberate scars did not (even though, in all likelihood, they were considerably more pronounced), we might think of Leah’s surgery as serving an integrative function. She compared what she calls the “burden” of her breasts and stretch marks to a large “ink stain” on a skirt that her surgery made smaller and less noticeable, making her “happier with [her] body” and her life more “manageable.” The stretch marked breasts are the accidental ink stain in Leah’s narrative of her body, and cosmetic surgery functions as a stain remover that tries to clean up and control this accident that is visible to everyone on the surface. Leah’s surgery allowed her to “look at [her] body and say okay, this is, like, this is what it is now, like things are not really going to change that much anymore.” Although it is likely that this statement is not true, and that her body will experience significant change throughout her life, Leah appears to have made herself more comfortable in her own skin through her surgery, and the surgery allows her to put some distance between her present and her past uncontrollable changes.

Tonya’s interview narrative is the most starkly contingent story, paralleling the contingency of the skin itself. When Tonya went for a physical in her early twenties, her family doctor found a lump in her breast and she was referred to a specialist. The lump turned out to be benign, but at this appointment the specialist asked Tonya if she had ever considered a breast reduction. This off-the-cuff question turned out to be the spark for a series of appointments that led to Tonya’s breast reduction. Tonya had never before considered the possibility of a breast reduction. Her narrative is conceptually structured around unknowingness. Very early in the interview, when Tonya discussed seeing the “boob specialist” who first suggested the breast reduction, she said that she had never even heard of breast reduction, and so she had never considered it. Tonya also said that she had no idea about differences between surgeons and the high variation of skill levels in surgery. When describing her constipation post-surgery, she said that she “never even heard of constipation.” The pain she experienced was unfamiliar, a “whole body” pain that was unlike the familiar pain of cuts and burns. The unknown, like the contingent and accidental, is impossible to predict. Tonya tells a surface imagination narrative that envisions a deeper truth beyond the surface (medical procedures beyond the routine physical, layers of surgical skill, interruptions to unthinking digestive function, and deep interior pain). Tonya presented her experience with cosmetic surgery as a journey in which she navigated through unknown surface imagination territory in order to change her detested breasts.

Tonya’s narrative is one of lucky accidents that occur as she works through unknown circumstances. While Tonya expressed feeling unconcerned about side effects or possible mishaps, this did not mean that she approached her surgery without any anxiety. For example, she was very concerned that she would be required to remove the barbell in her tongue piercing prior to her surgery. She was grateful to have her mother present for her surgery because her mother could be relied on to replace the barbell after the surgery. Tonya commented that she does not “know why, maybe [she] was just fixating on that, maybe [she] was just projecting all of this anxiety that I was not allowing myself to have onto my tongue ring,” and that perhaps what she was trying to do was “regain a sense of self after [her] operation.”

Because Tonya’s experience with her doctor was so alienating and distanced, it makes sense that she would place such a high value on retaining the tongue piercing after the surgery. Tonya felt the removal of the barbell as a de-personalization that transformed her body into the generic body of a breast reduction surgery patient. She felt this acutely in her appointments with the doctor, who made no eye contact and had no time for her questions. This hole in the tongue’s skin might be thought of as an integrative hole before and after Tonya’s surgery. In other words, Tonya’s “fixation” on the barbell is a struggle to make sense of, and gain some control over, what feels like an unruly bodily experience.

The next contingent skin happening that Tonya discussed at length was the removal, resizing, and replacement of her nipples during the surgery. Breast reduction surgeries are commonly performed by removing the nipples and then creating a vertical incision from the nipple that extends into the crease underneath the breast (sometimes referred to as the “anchor incision” due to its appearance). Tissue is removed from the breast, the breast is reshaped and lifted, and the incisions are closed. At the same time, the nipple is cut to a smaller size and then reattached in a higher position. Tonya was fascinated by this procedure, and describes it as both “weird” and “awesome,” saying that “all [she] could think of was like [her] nipple just being beside [her] on the, like in a little Petri dish.” What Tonya describes is a fantasy of separating from one’s skin, as a way of experiencing greater closeness and intimacy with the world and others. Her fascination about the post-surgical nipples combines the fantasy of escaping the skin, the integrative function of cutting into the skin, and is a symbol for her of controlling this experience and her body. As I was packing up after our interview, Tonya told me that she got a tattoo on her chest after the surgery as a “finishing touch.” This is entirely consistent with the trajectory of Tonya’s story, which moves from the contingent and unknown qualities of her skin and the surgery to asserting control over the surgical event that was happening upon her body. The importance of replacing the tongue piercing, the fascination of the removed and restored nipple, and the conclusion of the tattoo are connected together as responses to the accidental and contingent traits of Tonya’s surgical narrative.

While Victoria’s and Diana’s narratives are quite different from those of Tonya, Leah, and Tigerlily, they share a frustration with the skin’s obstinacy and refusal to respond to their efforts to change their skins. Victoria explains her skin’s contingency through the uncontrollability of biological activity (hormones and reactions to food). Her hopes that what she was experiencing was just a “hormonal thing” set limits on the skin’s predictability: eventually, the skin-sky will clear up, so to speak. The primary way that Victoria tried to control her skin was through diet, but eventually she realized that her skin was “very infected” and that she could not control the unruly bacteria on her face. Victoria’s solution traded one contingent situation for another. While her acne is uncontrollable and she is not able to predict how it will react to various food, hormonal, and stress situations, the treatment she receives is similarly unpredictable and “depend[ant] on how [her] skin reacts.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree