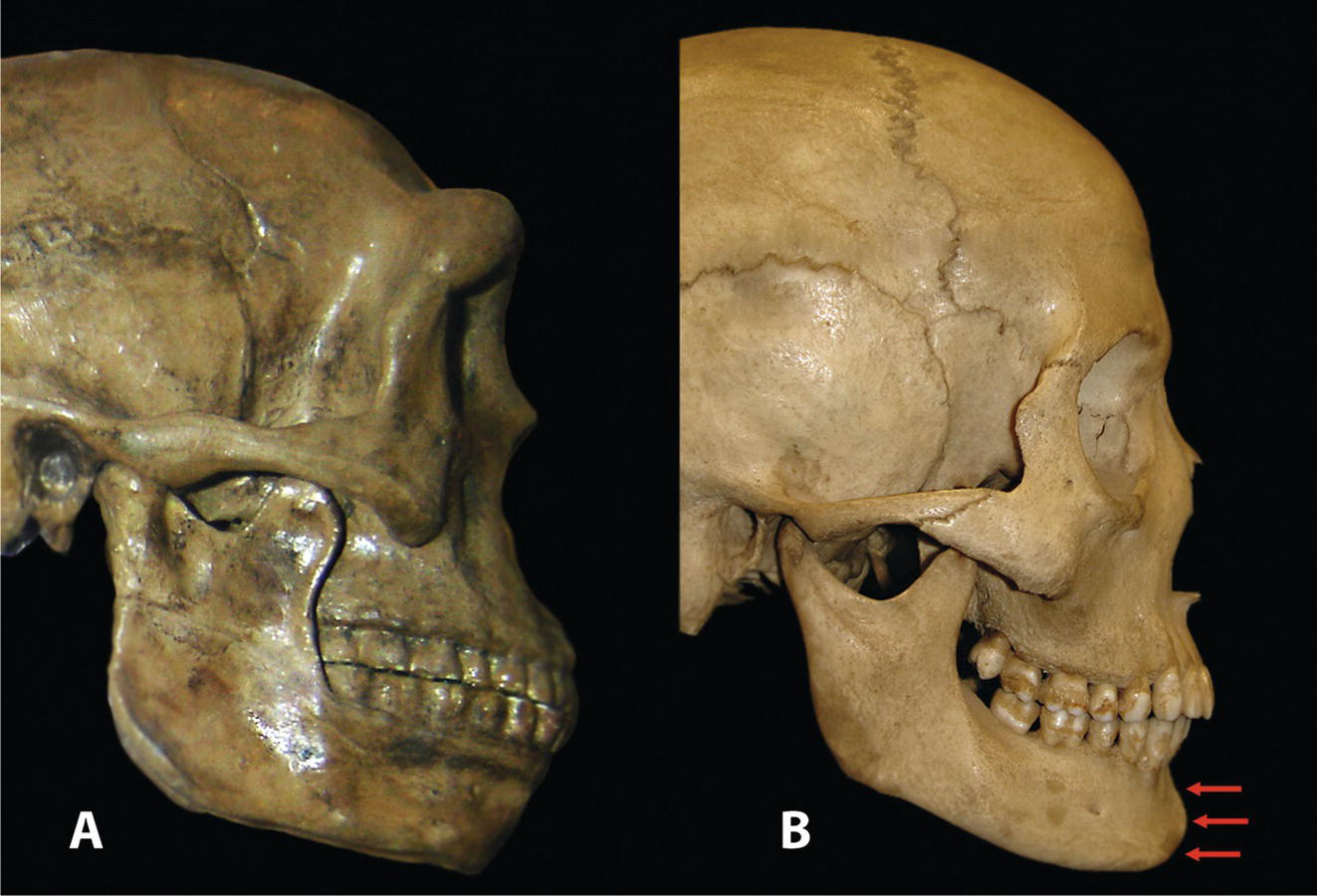

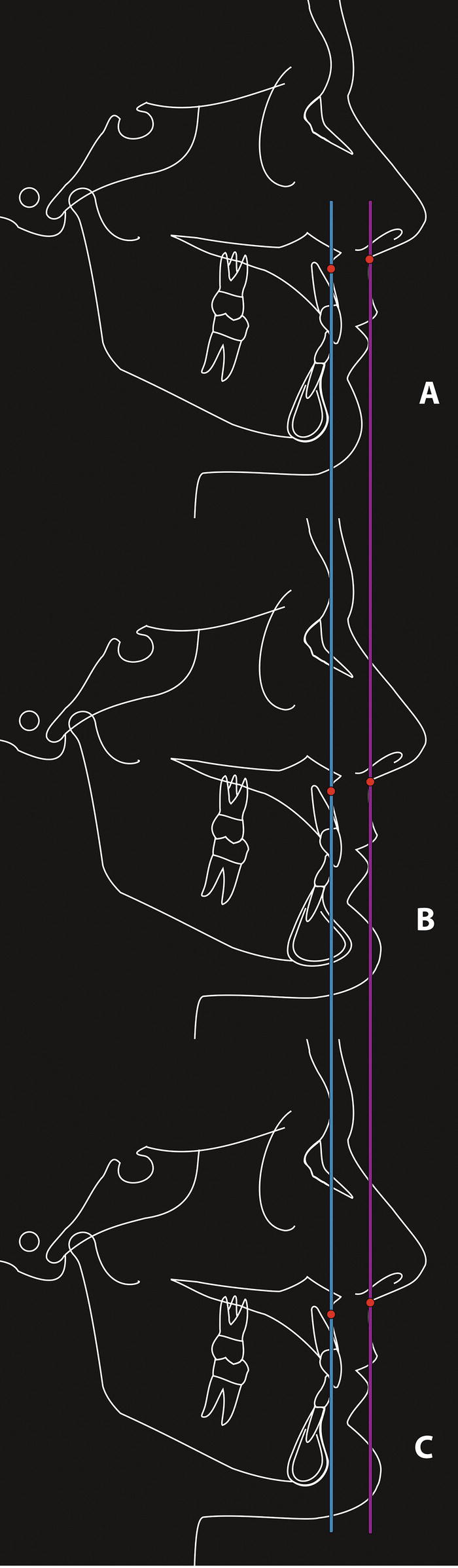

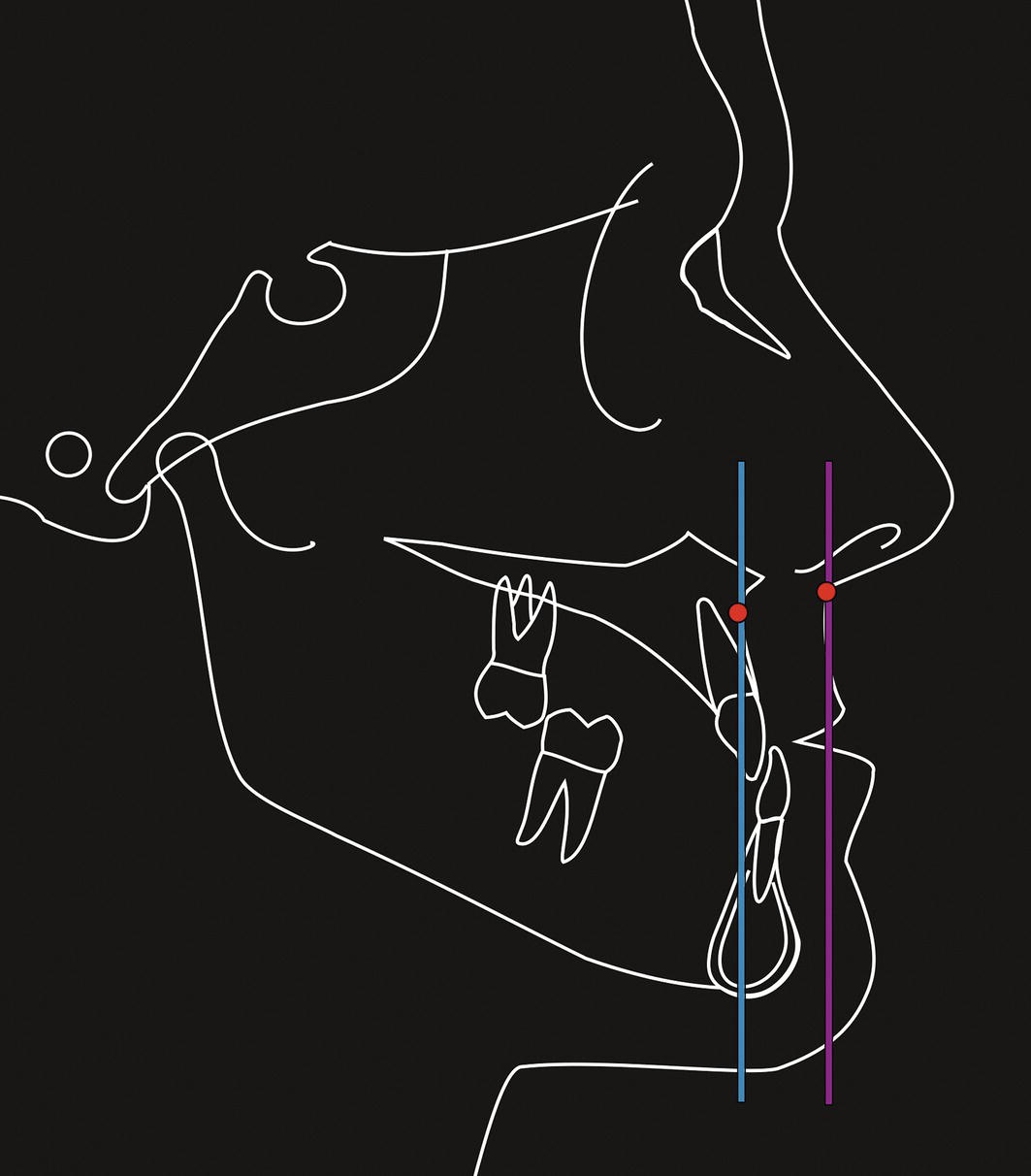

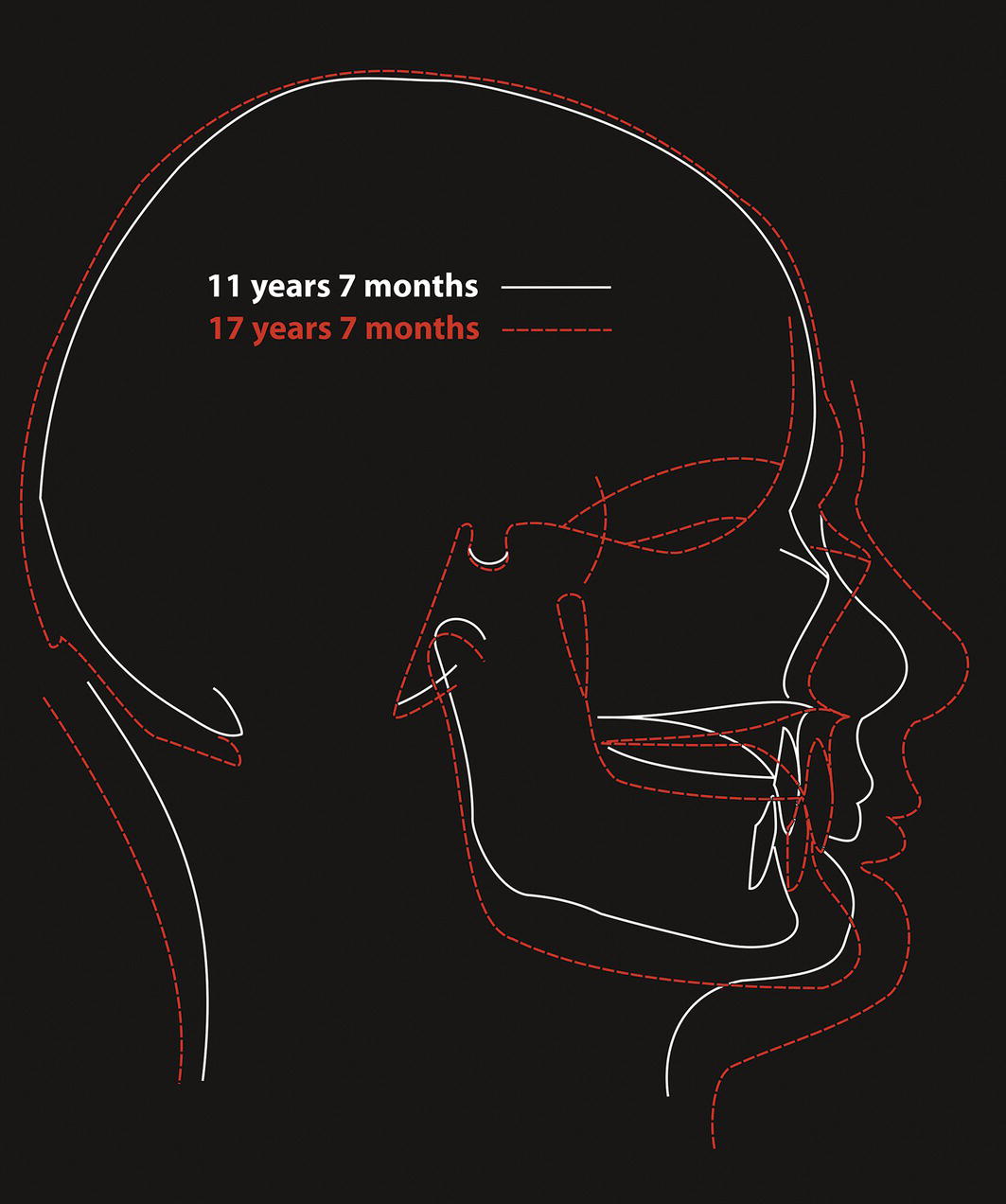

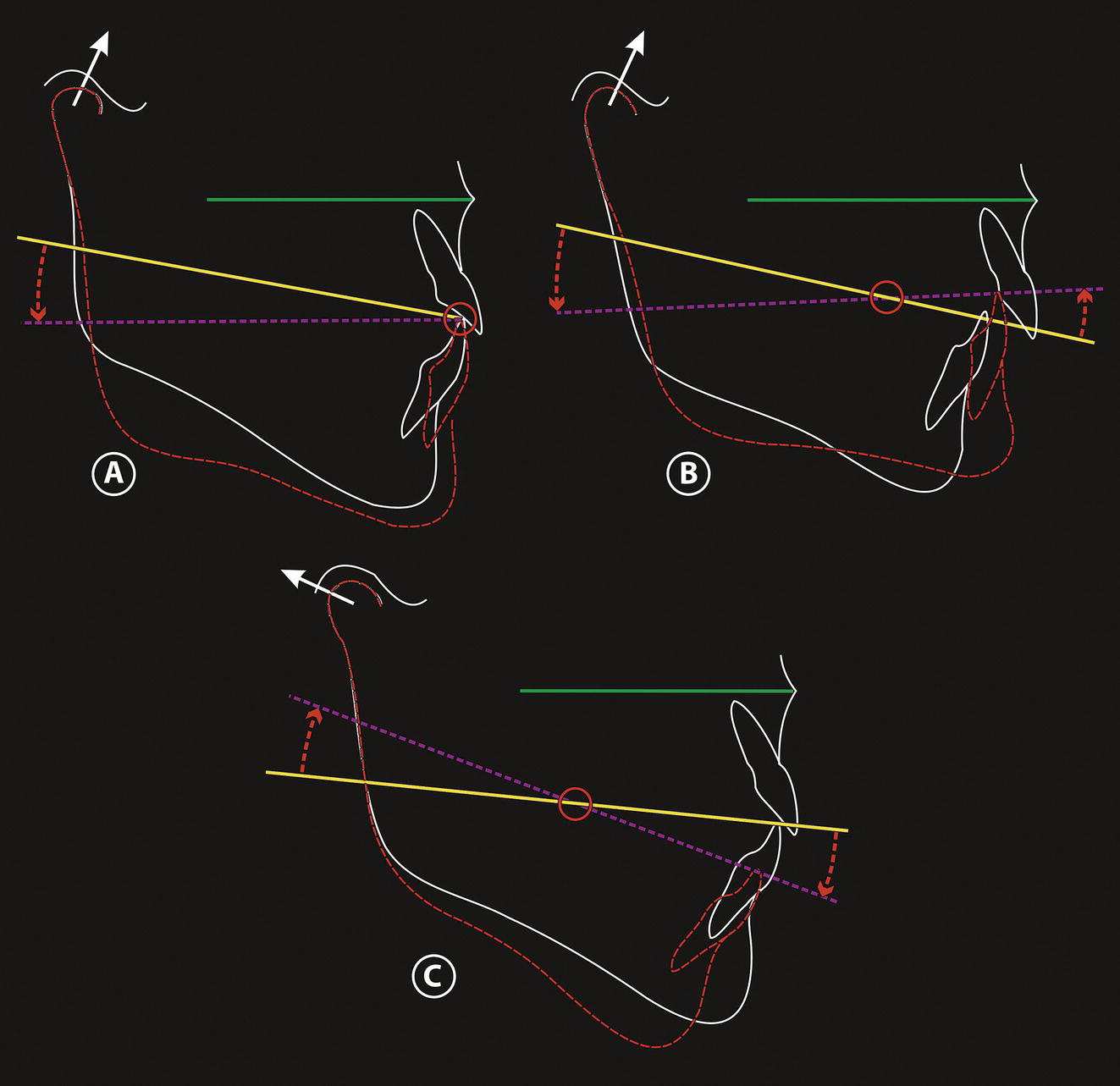

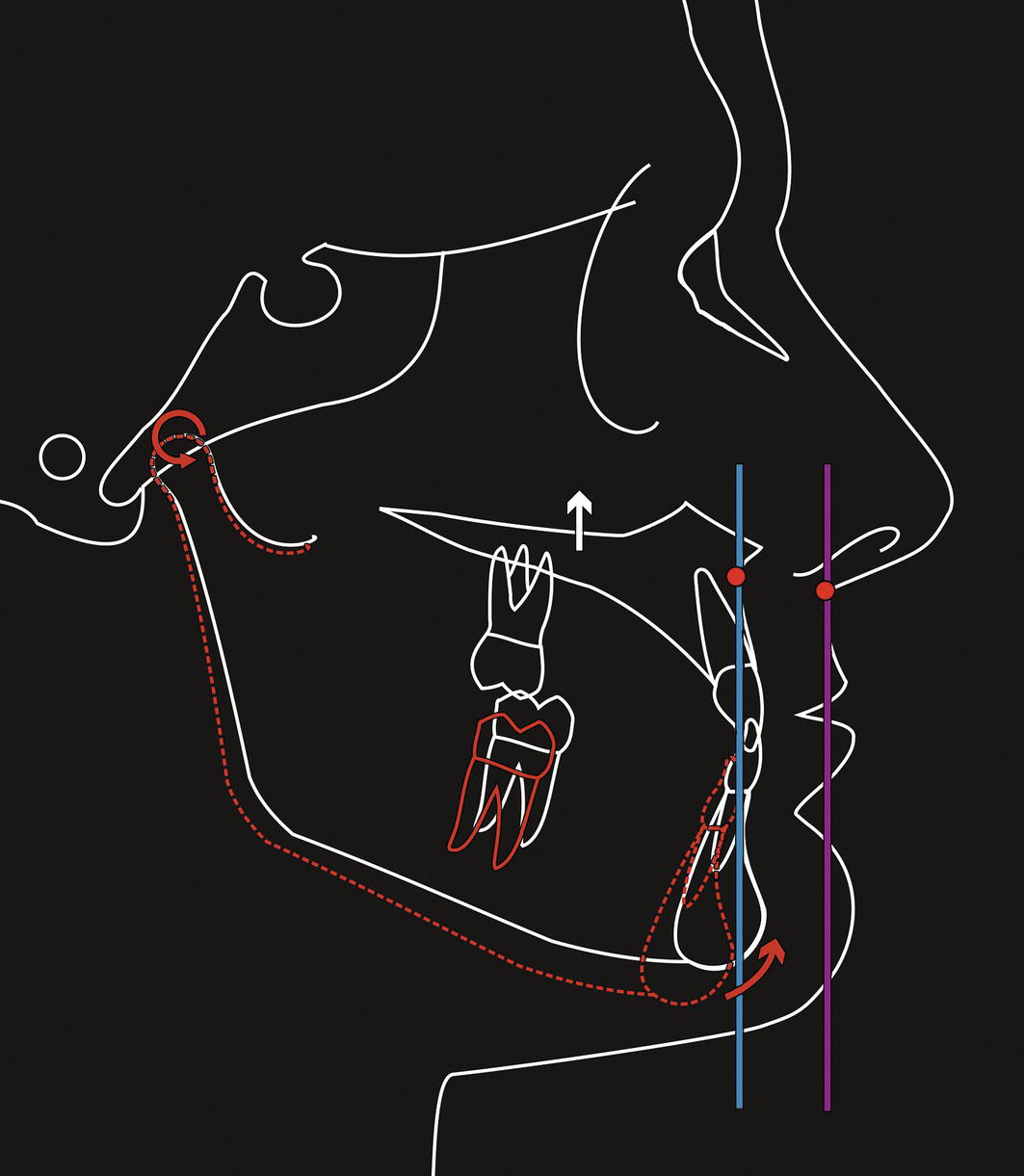

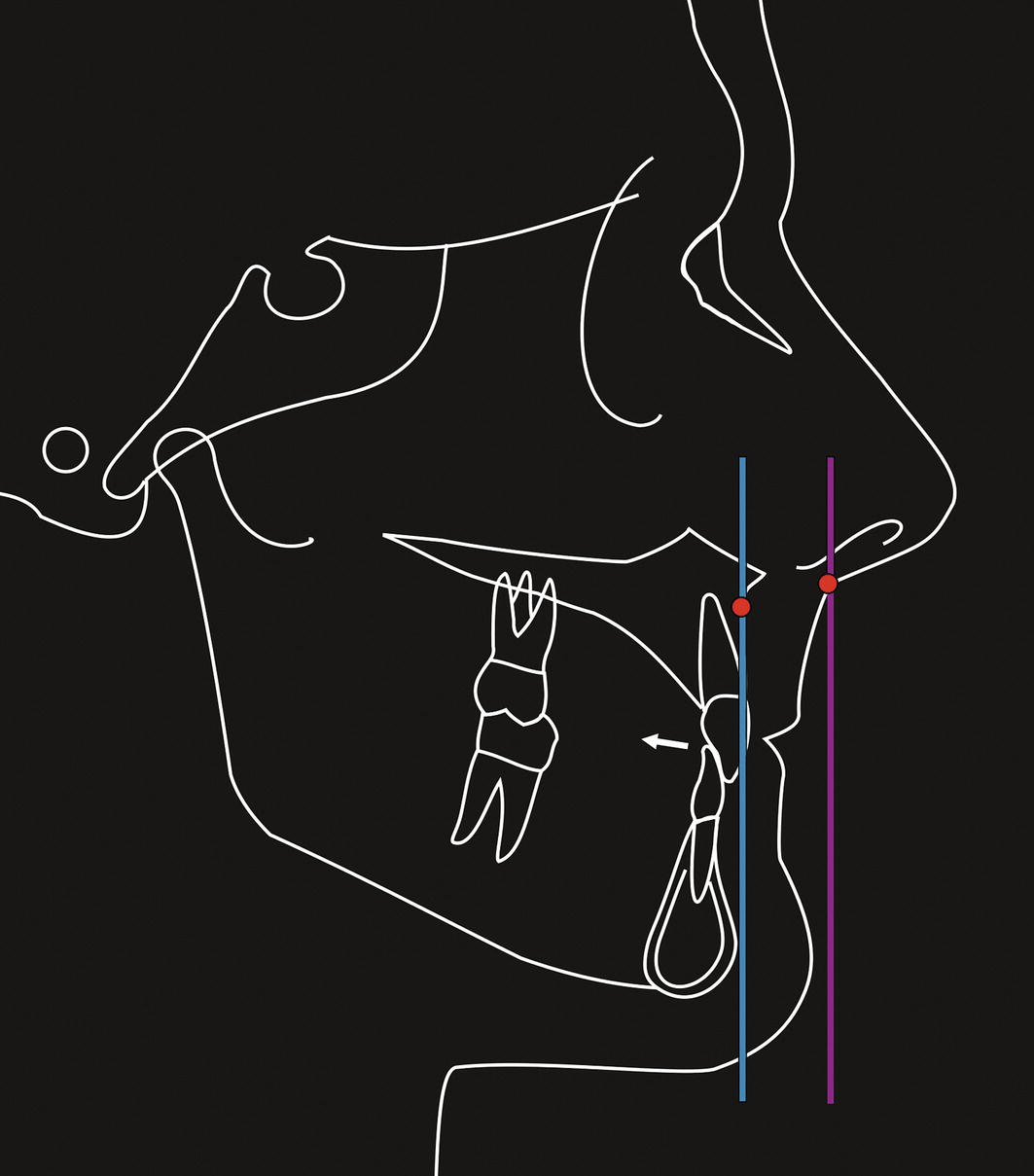

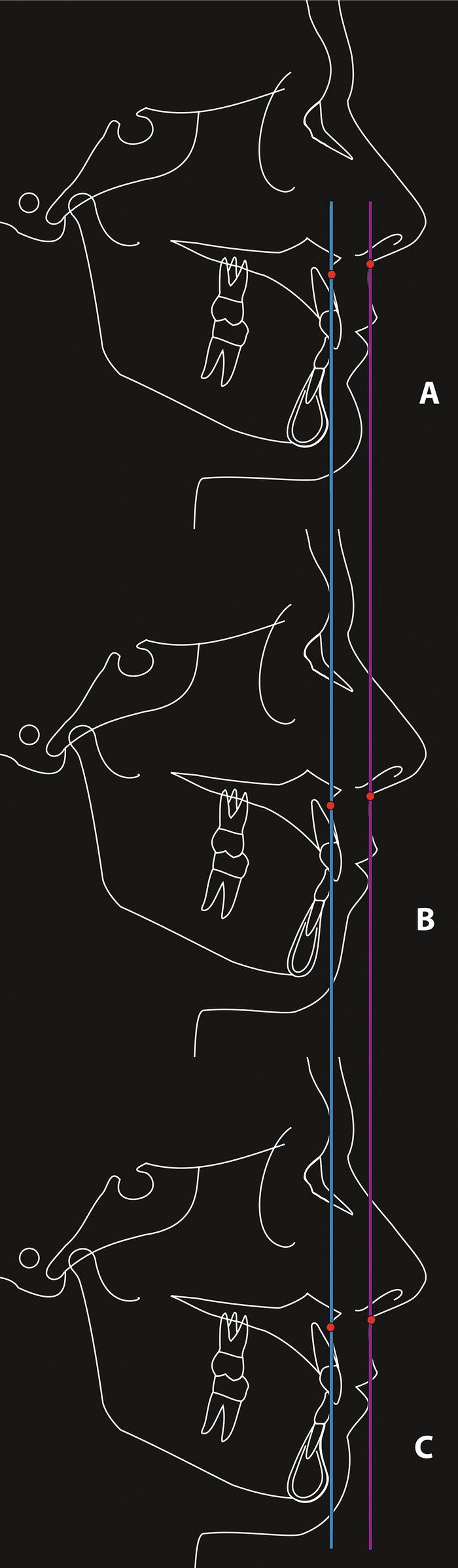

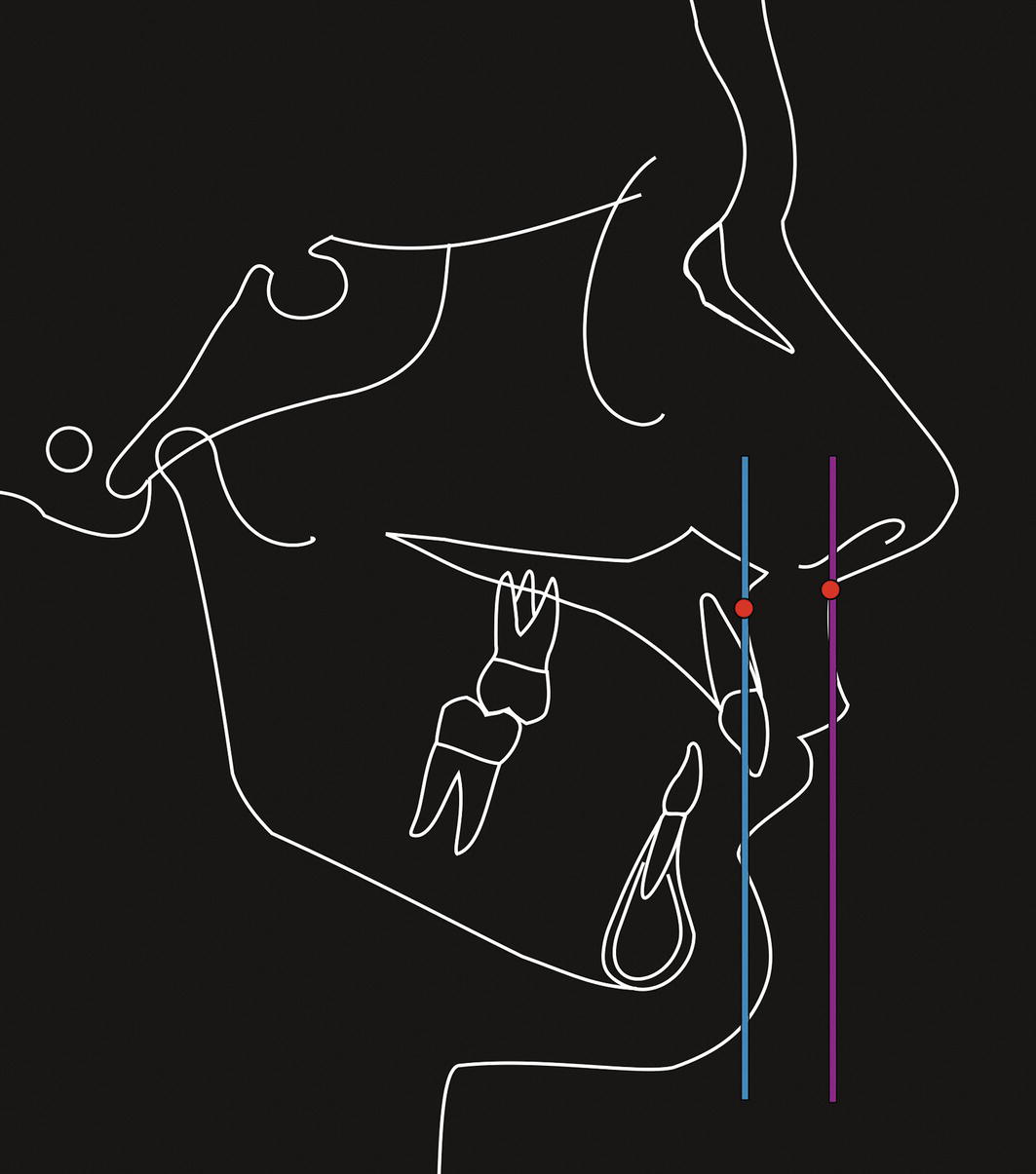

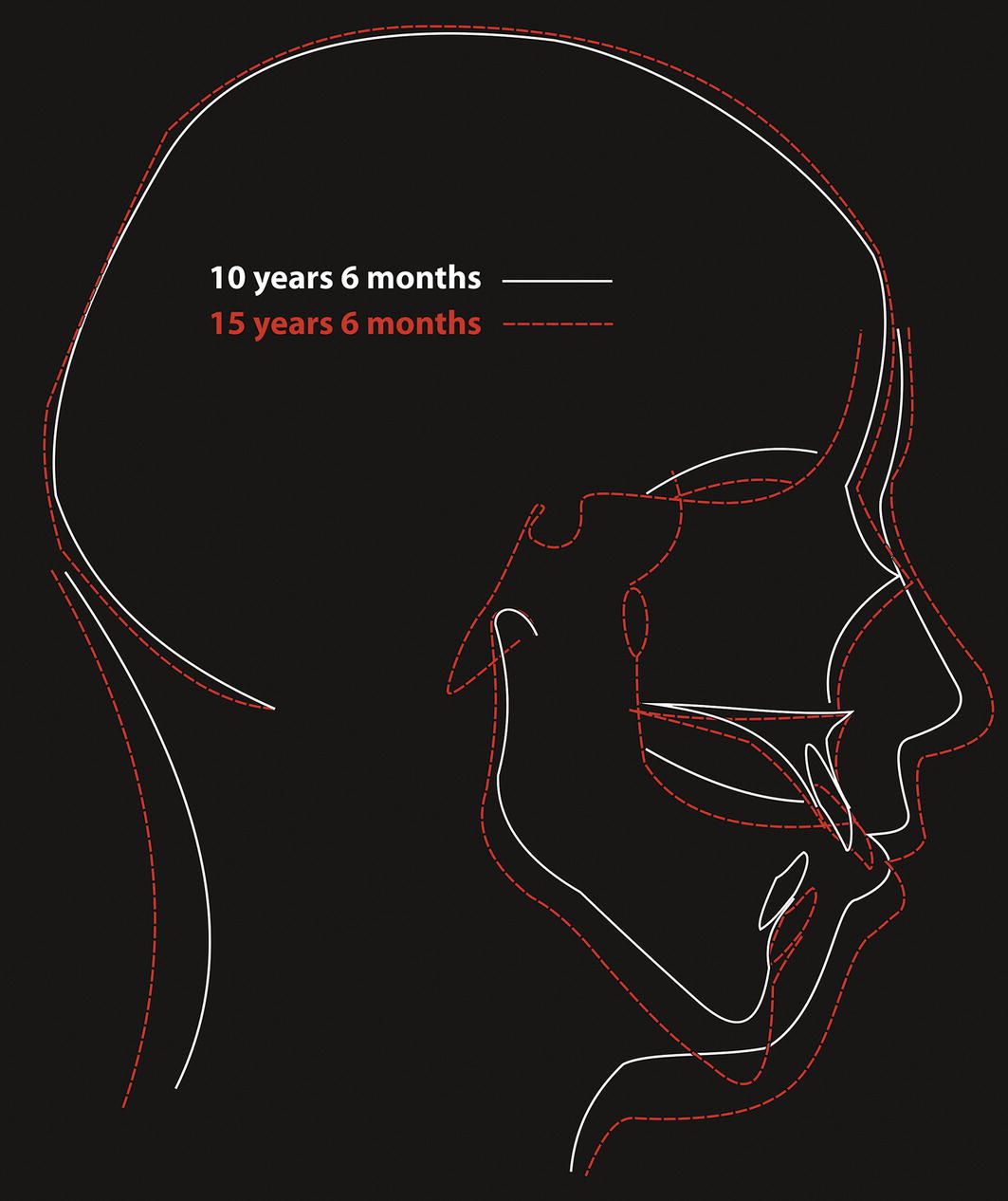

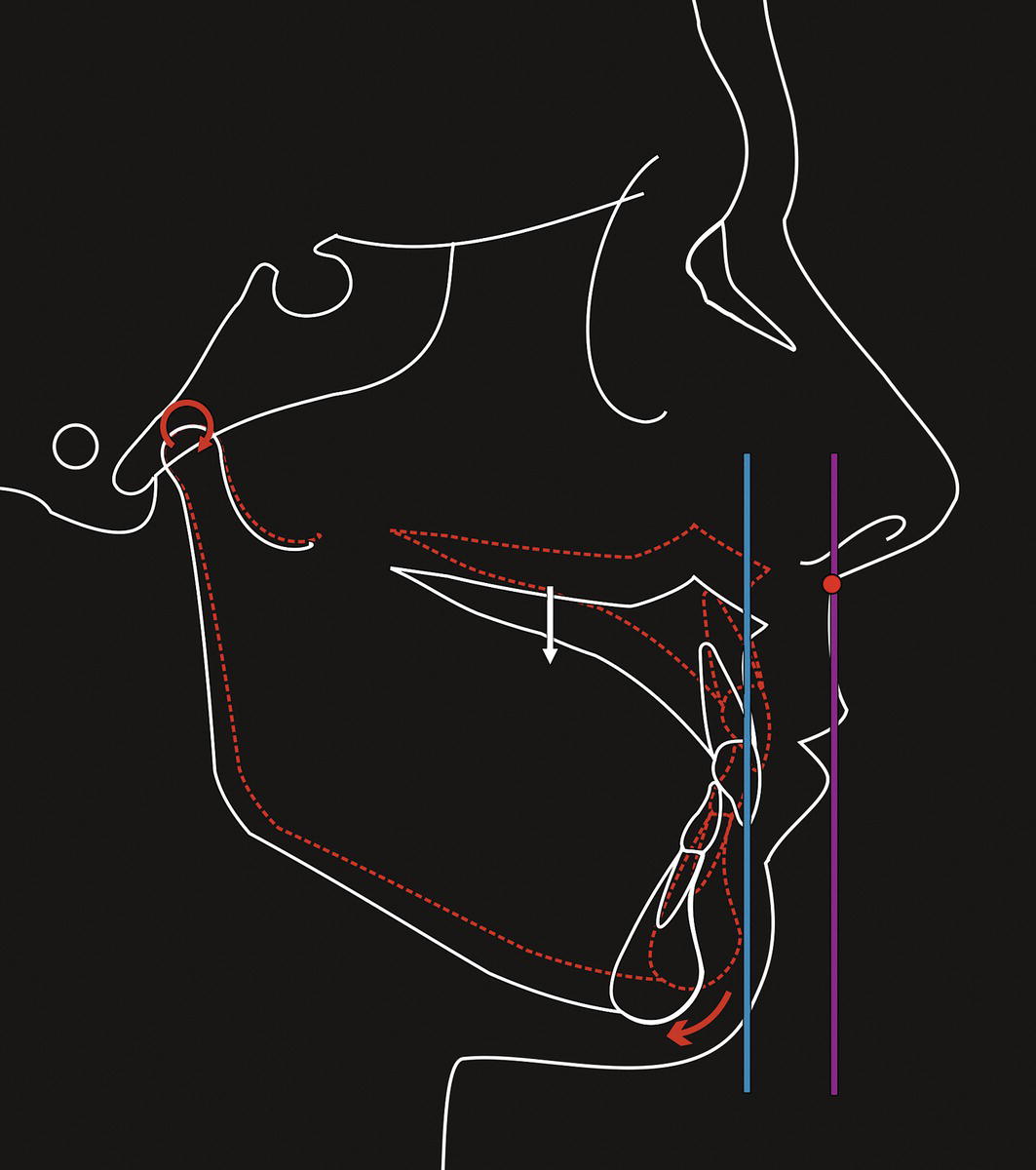

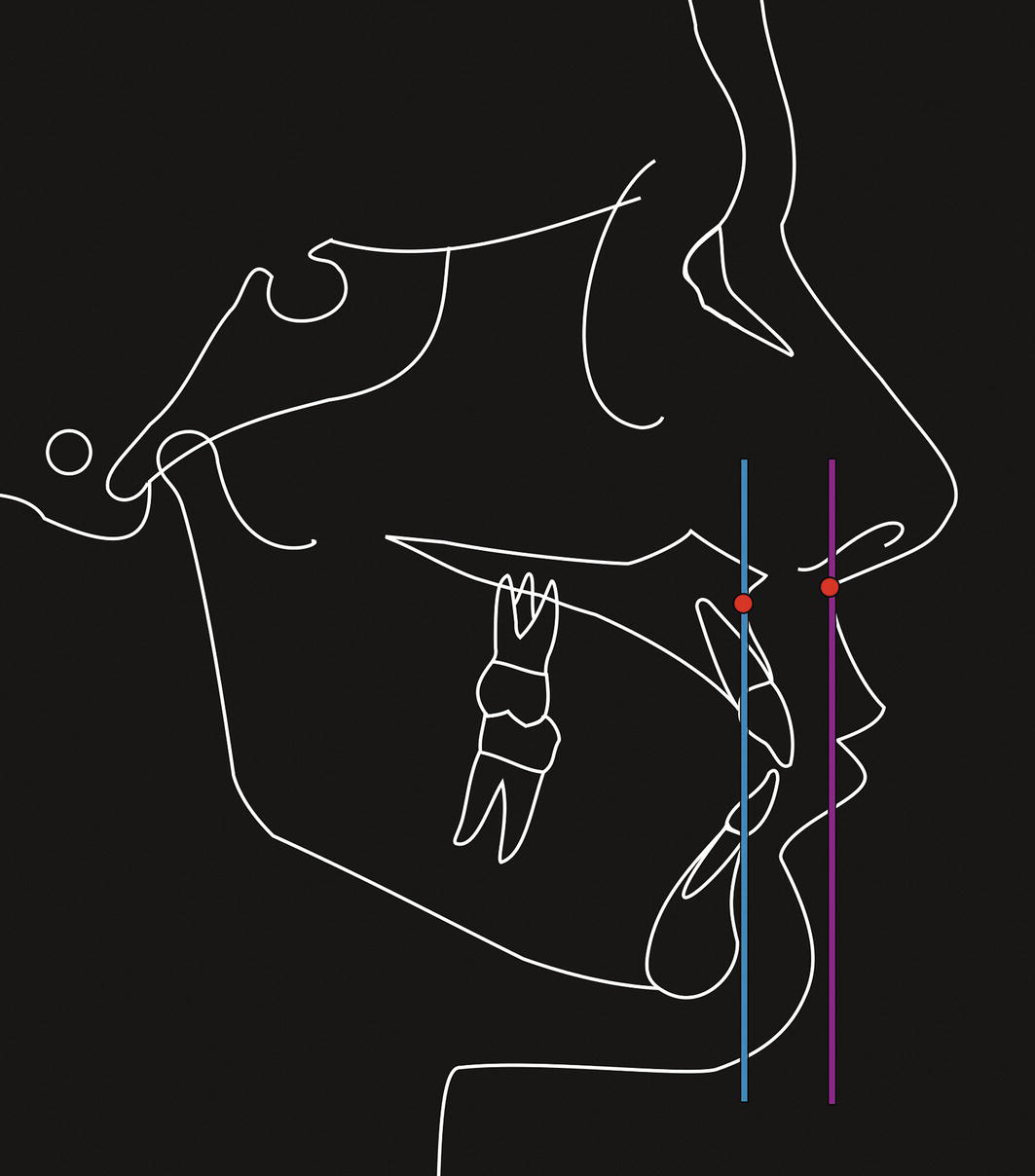

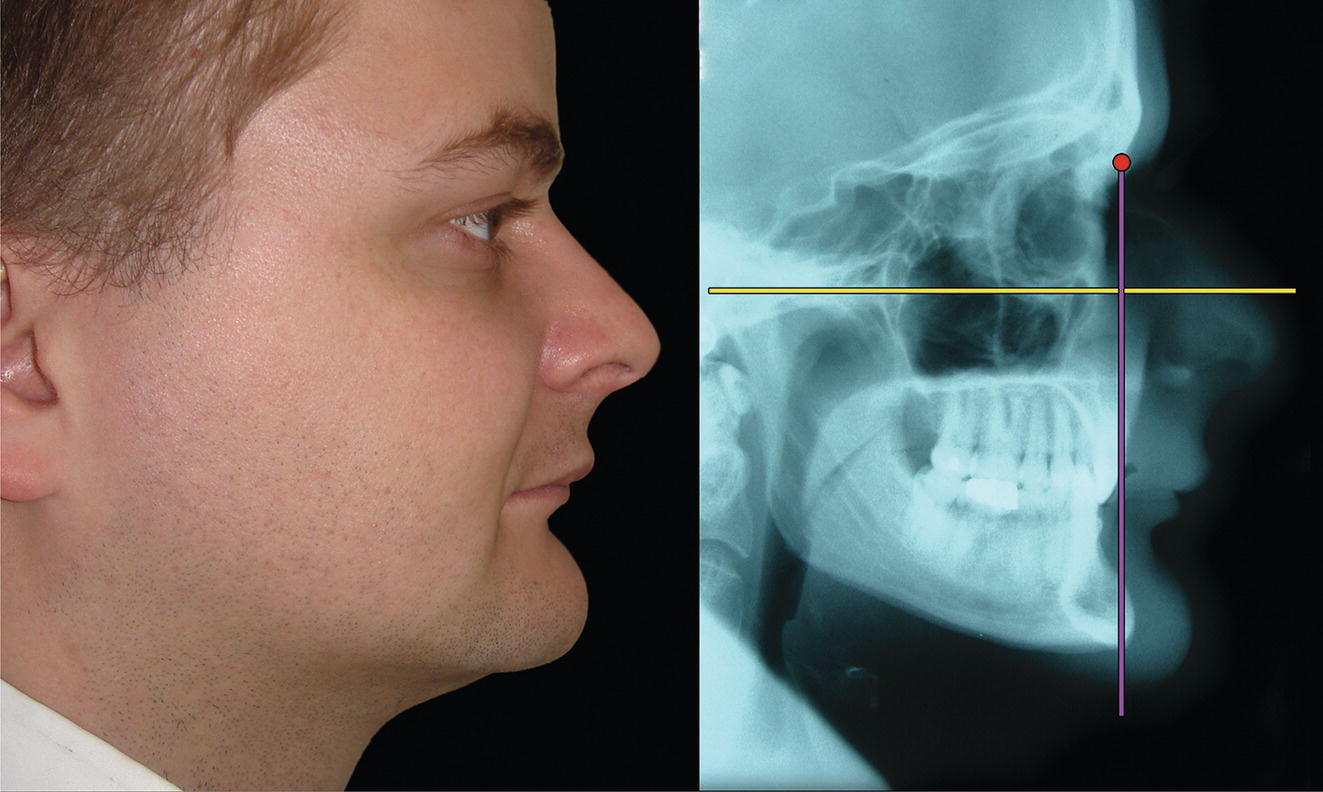

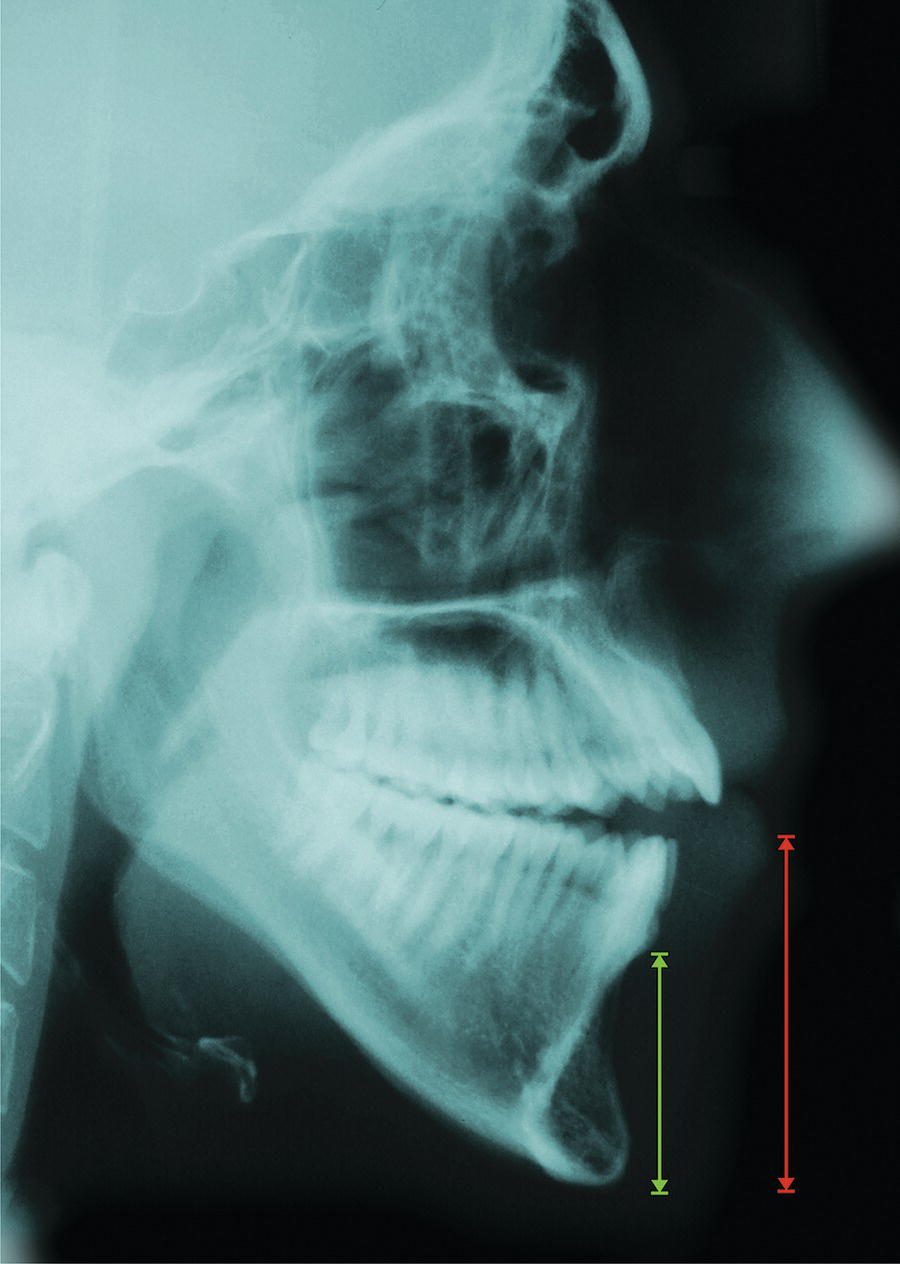

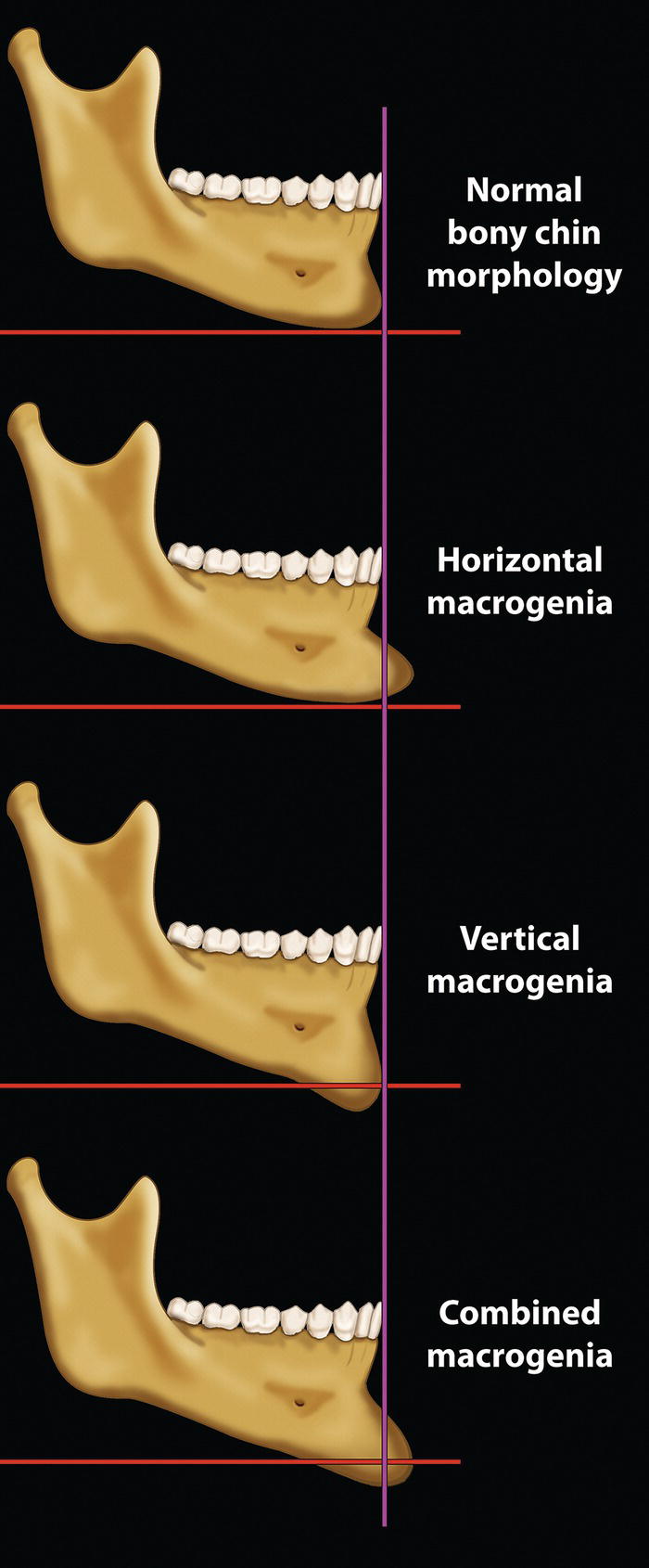

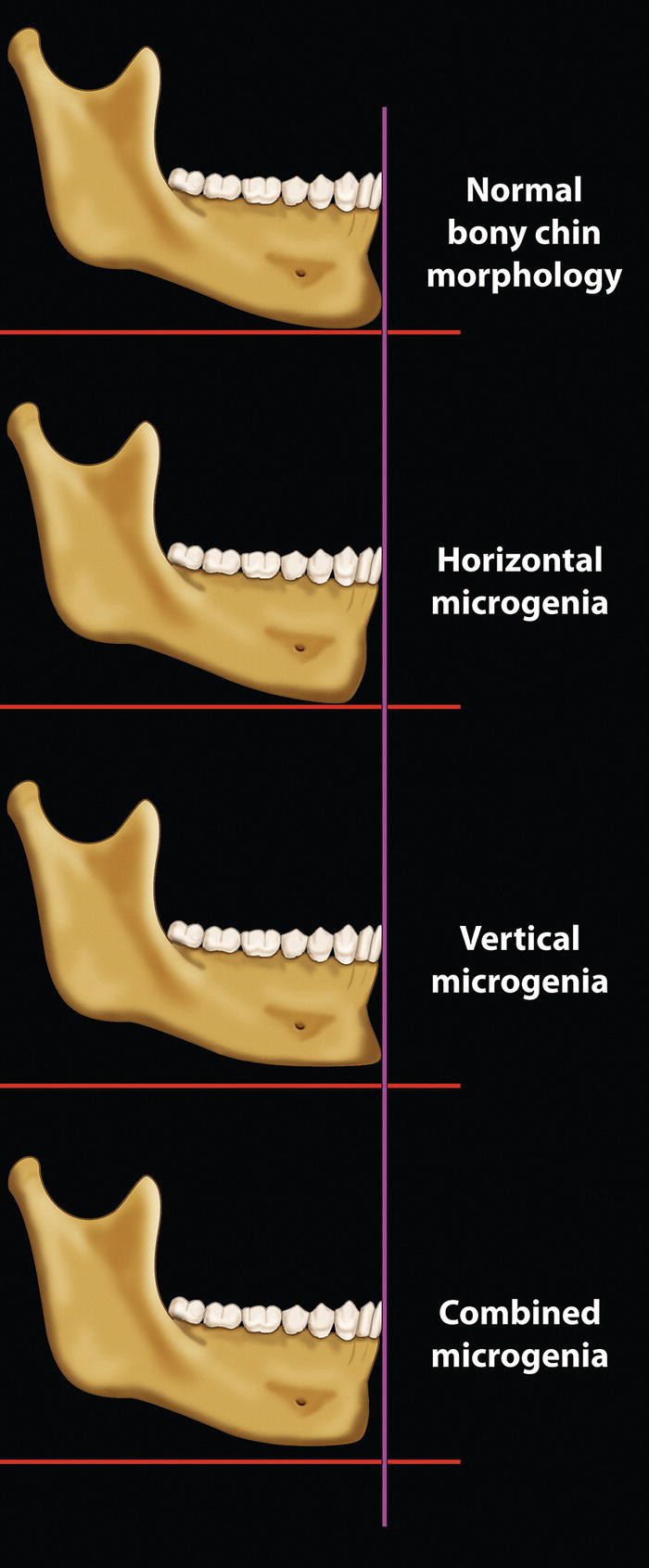

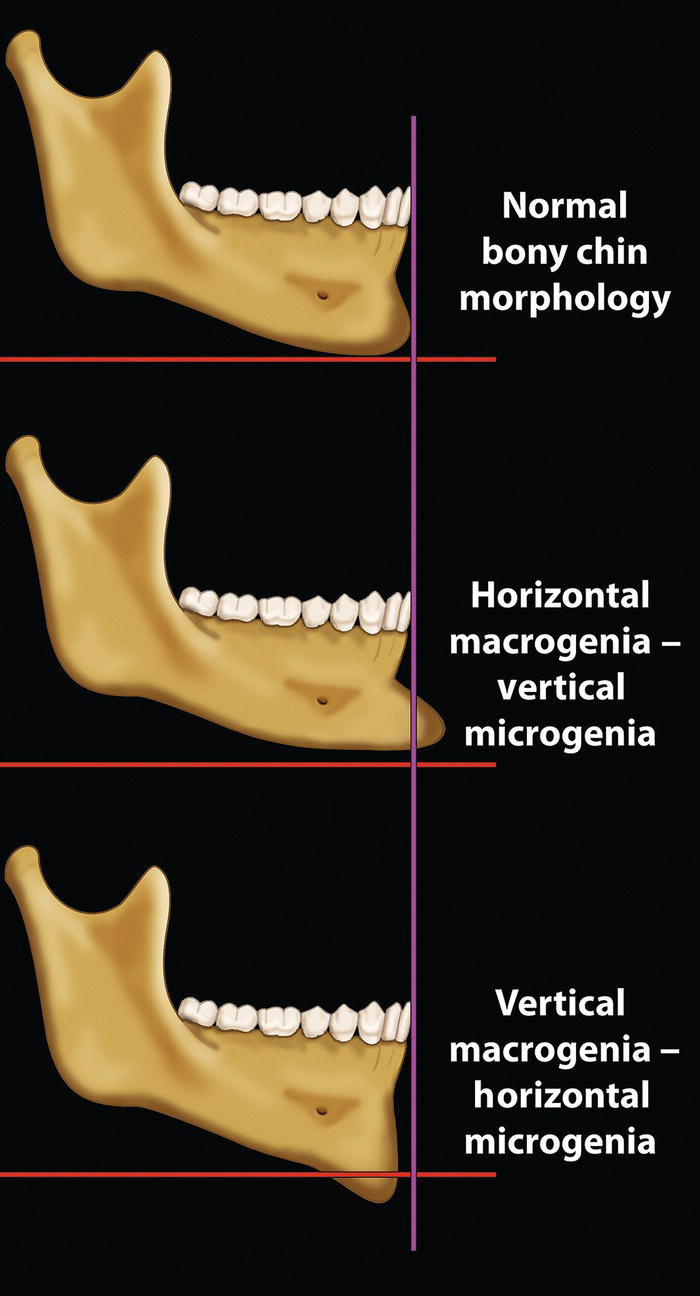

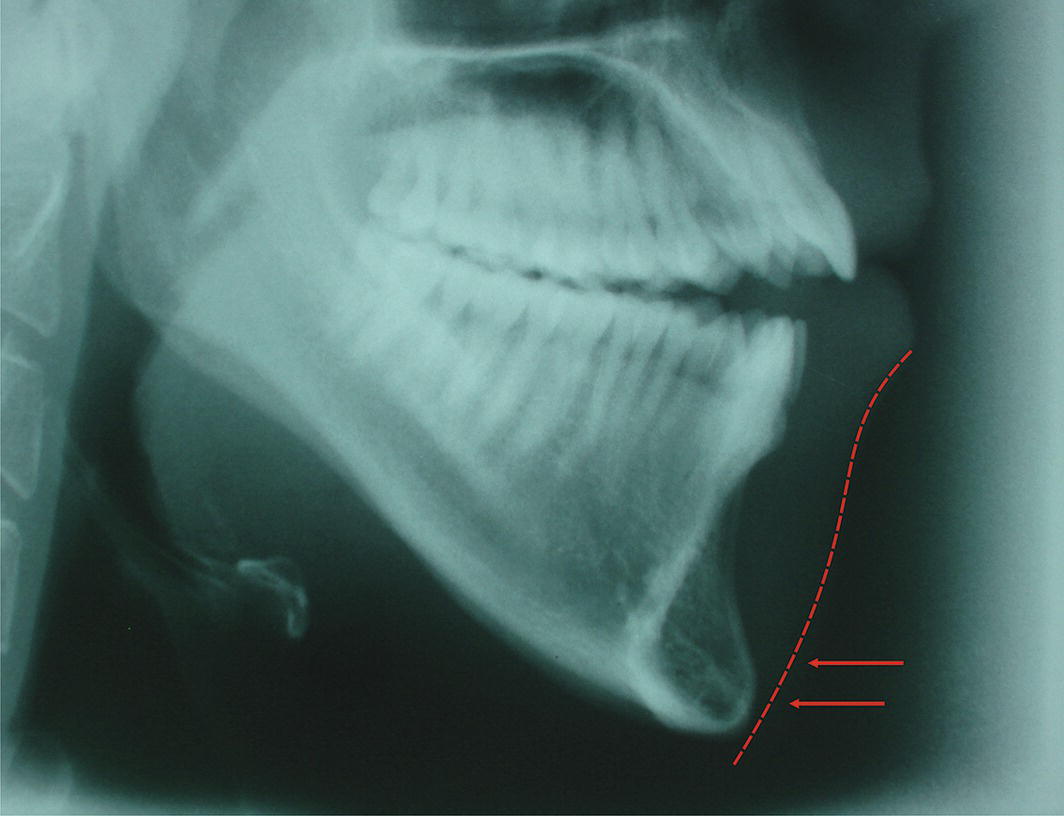

‘Thou whose features clearly beaming make the moon of Beauty bright, Thou whose chin contains a well‐pit which to Loveliness gives light’. Hafez (1325–90) Persian poet‐philosopher1 The chin is unique to humans. The human face as we know it originated with the Homo sapiens in Africa, approximately 130 000 years ago. Even Neanderthals retained a modest muzzle, whereas the need for a projecting mouth all but disappeared in modern humans. This flattening of the face and retrusion of the orodental complex coincided with the appearance and projection of the bony chin, perhaps a remnant of the now obsolete muzzle (Figure 20.1). The morphology of the chin has a substantial influence on the perceived attractiveness of the face. In profile view, in particular, the chin establishes much of the character of the lower face (Figure 20.2). In fact, the prominence of the chin is one of the facial characteristics that society tends to associate with an individual’s personality. Individuals, particularly men, with a deficient chin may be viewed as ‘weak’, whereas a prominent chin is often described as a ‘strong’ chin, implying strength of personality. The history of aesthetic chin surgery has been described comprehensively elsewhere.2Otto Hofer (1942) is likely to have been the first surgeon to propose a horizontal osteotomy of the mandibular symphysis and sliding advancement of the inferior fragment.3 The procedure was performed from an external approach and the ‘patient’ seems to have been a cadaver. The first report of aesthetic chin surgery in a living patient seems to be that of Sir Harold Gillies and Ralph Millard Jr (1957).4 The procedure was performed through an external approach, with the inferior fragment being advanced and positioned superiorly, anterior to the upper mandibular fragment; this procedure is now termed a ‘jumping genioplasty’. Richard Trauner and Hugo Obwegeser (1957) later reported aesthetic chin surgery through an intraoral approach, and coined the term ‘genioplasty’.5John Converse and Donald Wood‐Smith (1964) reported their results through an intraoral approach, referring to the procedure as a ‘horizontal osteotomy of the mandible’.6Thomas Hohl and Bruce Epker (1976) discussed vertical reduction of chin height by wedge ostectomy.7Kevin McBride and William Bell (1980) discussed increasing the height of the chin with autogenous interpositional bone graft.8 Anatomically the chin is the area below the mentolabial fold, although separating the chin from the lower lip in patients with a poorly defined mentolabial fold can be difficult, particularly in frontal view. The anatomy, morphology and aesthetics of the lower lip, mentolabial fold and chin are intimately related. The chin consists of the bony anterior projection of the mandible, called the mandibular or mental symphysis, and its overlying soft tissue chin pad. Figure 20.1 (A) Cranioskeletal morphology of Homo erectus, a species of hominid (of the human family) that walked upright and lived more than one million years ago. (With kind permission, © Natural History Museum, London.) (B) Cranioskeletal morphology of modern human (modern Homo sapiens) demonstrates the differences between the two species: Homo sapiens has a larger cranium, a taller forehead, reduced prominence of the brow ridge, reduced mandibular length, reduced bimaxillary protrusion, smaller teeth and a pronounced bony chin. Figure 20.2 The chin establishes much of the character of the lower face, particularly in profile view. (Detail, Study for the Face of Leda, Michelangelo, c. 1530, Casa Buonarroti, Florence.) The ability to accurately describe and thereby classify facial deformities is essential, and a prerequisite to correct diagnosis, leading to correct treatment planning. An important step towards classification is therefore to define the clinical terminology based on etymology. The terminology used should reflect the underlying aetiology. The terms ‘chin excess’ and ‘chin deficiency’ may be used to describe chin deformities in the sagittal or vertical plane. Progenia is a term used to indicate that the sagittal position of soft tissue pogonion (Pog′, the most prominent point on the soft tissue contour of the chin, in the midsagittal plane) is protrusive (too far forward) in relation to the rest of the craniofacial complex. This may be due to a relatively larger size (macrogenia) and/or a more anterior position of the chin. Progenia is a non‐specific term describing the sagittal position of the chin, not the underlying aetiology. Progenia may be classified as primary, secondary or ‘relative’. Primary progenia (primary sagittal chin excess): This is a structural problem, describing a morphological deformity of the chin area. An alternative and preferred term is ‘sagittal chin excess’. The aetiology of sagittal chin excess may be due to one or a combination of the following: Figure 20.3 (A) Normal chin prominence. (B) Horizontal osseous microgenia. (C) Increased thickness of soft tissue chin pad. Figure 20.4 Sagittal chin excess secondary to mandibular excess (i.e. normal chin morphology on a prominent mandible). Secondary progenia (secondary sagittal chin excess): This is a positional problem of the mandible, describing the forward position of the chin as a result of an excessively forward position of the mandible, i.e. the morphology of the chin is normal; the abnormal position of the chin is secondary to the abnormal position of the mandible, with the normal chin being carried forward on the mandible. The aetiology of secondary progenia may be due to one or a combination of the following: Figure 20.5 Horizontal, hypodivergent (short face type) facial growth pattern, leading to an increased sagittal projection of the chin. (Modified from Björk9 with permission from Informa Healthcare, Taylor and Francis Group.) ‘Relative’ progenia (relative sagittal chin excess): The chin appears protrusive (too far forward) due to lower labial or bilabial retrusion, i.e. the lower lip or both lips being positioned too far back in relation to the craniofacial complex (Figure 20.8). Retrogenia is a term used to indicate that the sagittal position of soft tissue pogonion (Pog’) is retrusive (too far back) in relation to the rest of the craniofacial complex. This may be due to a relatively smaller size (microgenia) and/or a more posterior position of the chin. Retrogenia is a non‐specific term describing the position of the chin, not the underlying aetiology. Retrogenia may be classified as primary, secondary or ‘relative’. Primary retrogenia (primary sagittal chin deficiency): This is a structural problem, describing a morphological deformity of the chin area. An alternative and preferred term is ‘sagittal chin deficiency’. The aetiology of sagittal chin deficiency may be due to one or a combination of the following: Secondary retrogenia (secondary sagittal chin deficiency): This is a positional problem of the mandible, describing the retrusive position of the chin as a result of an excessively retropositioned mandible, i.e. the morphology of the chin is normal; the abnormal position of the chin is secondary to the abnormal position of the mandible. The aetiology of secondary retrogenia may be due to one or a combination of the following: Figure 20.6 Types of mandibular growth rotation. (A) Anterior (forward) mandibular growth rotation with the centre of rotation at the incisal edges of mandibular incisors; the direction of condylar growth is upward and forward. (B) Anterior mandibular growth rotation with the centre of rotation at the premolars. In both cases, the chin moves upward and forward, increasing chin projection. (C) Posterior (backward) mandibular growth rotation moving the chin downward and backward, effectively reducing the sagittal projection. (Modified from Björk and Skieller10/with permission of Elsevier.) Figure 20.7 Anterior mandibular autorotation around the condylar hinge axis will increase sagittal chin projection. Figure 20.8 Relative sagittal chin excess, with the chin appearing protrusive (too far forward) due to lower labial or bilabial retrusion. Figure 20.9 (A) Normal chin prominence. (B) Horizontal osseous microgenia. (C) Reduced thickness of soft tissue chin pad. ‘Relative’ retrogenia (relative sagittal chin deficiency): The chin appears retrusive (too far back) due to lower labial or bilabial protrusion, i.e. the lower lip or both lips being positioned too far forward in relation to the craniofacial complex (Figure 20.13). Figure 20.10 Sagittal chin deficiency secondary to mandibular deficiency (i.e. normal chin morphology on a small or retropositioned mandible). This term describes an increase in vertical skeletal chin height (Figure 20.15). Figure 20.11 Vertical, hyperdivergent (‘tall face’ type) facial growth pattern, leading to a reduced sagittal projection of the chin. (Modified from Björk9 with permission from Informa Healthcare, Taylor and Francis Group.) Figure 20.12 Posterior mandibular autorotation around the condylar hinge axis reduces sagittal chin projection. This term describes a reduction in vertical skeletal chin height. Guyuron et al. (1995)11 proposed a classification of chin deformities to be used as a guide to surgical treatment planning. They identified seven categories of chin deformities from 684 patients with normal dental occlusions. A modification of this classification is presented below: Skeletal chin (mandibular symphysis): Figure 20.13 Relative sagittal chin deficiency, with the chin appearing retrusive (too far back) due to lower labial or bilabial protrusion. Figure 20.14 Sagittal mandibular deficiency combined with horizontal macrogenia (sagittal chin excess). Figure 20.15 Vertical chin excess – lower anterior dentoalveolar and chin height is increased primarily as a result of an increase in skeletal chin height. Figure 20.16 Macrogenia – types of skeletal chin excess. Figure 20.17 Microgenia – types of skeletal chin deficiency. Figure 20.18 Combined skeletal chin deformity. Soft tissue chin pad: Mandibular rotation: Mandibular position and/or size: Figure 20.19 Increased thickness of soft tissue chin pad (bony chin is relatively underdeveloped). The morphology of the mandible tends to be relatively consistent depending on the presenting facial deformity, e.g. a Class II, Class III, tall face or short face individual tends to have a ‘typical’ mandibular shape. The chin is part of the mandible; however, the morphology of the osseous chin, or mandibular symphysis, and the overlying soft tissue chin pad is highly variable in all three planes of space, even with the same basic types of facial deformities. Therefore, the chin must be evaluated as an independent facial aesthetic subunit. When evaluating the chin, the following patient positioning guidelines should be observed: Figure 20.20 Reduced thickness of soft tissue chin pad (mentalis hypertrophy is evident at a higher level to the chin). Figure 20.21 Ptosis of the soft tissue chin pad in repose and in animation.

Chapter 20

The Chin

Introduction

Anatomy

Terminology

Chin excess and chin deficiency

Progenia (sagittal chin excess)

Retrogenia (sagittal chin deficiency)

Vertical chin excess (VCE)

Vertical chin deficiency (VCD)

Classification of chin deformities

Clinical evaluation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree