The Auricular Region

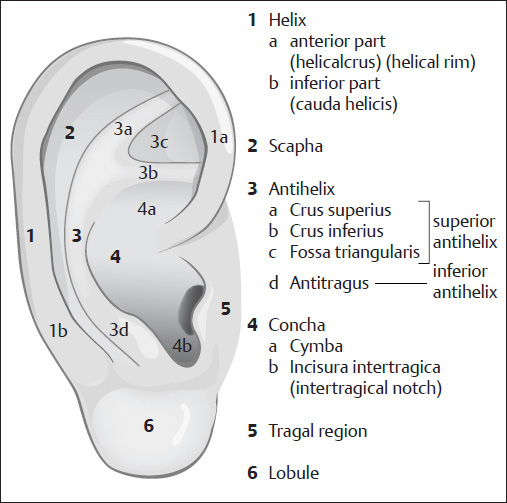

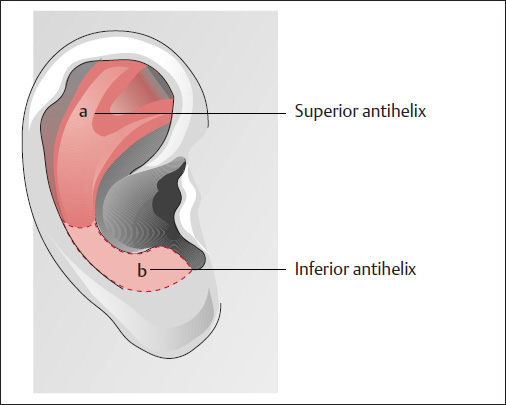

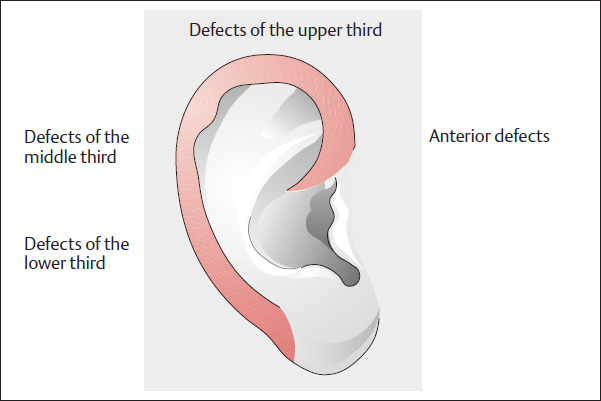

Classification (Table 10.1) and Esthetic Units (Fig. 10.1)

Although there will inevitably be overlaps when attempting to classify auricular defects, we still regard it as worthwhile to classify the defects for didactic reasons, to offer a system of surgical reconstruction (Weerda 1980b, 1984, 1987, 1989c, 1994d, 2001; Weerda and Siegert 1999a; Mellette 1991) ( Table 10.1 ). The esthetic units ( Fig. 10.1 ) cannot always be taken into consideration, and reconstruction of the auricle is performed in accordance with surgical requirements (see Weerda 2004, pp. 1–3, 12).

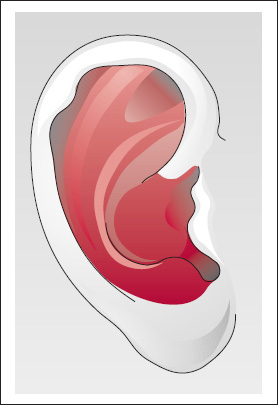

Central Defects: Recommended Defect Coverage (Fig. 10.2)

1. Central defects

|

2. Peripheral defects

|

3. Partial Reconstruction of the auricle

|

4. Reconstruction of the earlobe

|

5. Posterior defects

|

6. Subtotal defects |

7. Loss of the auricle

|

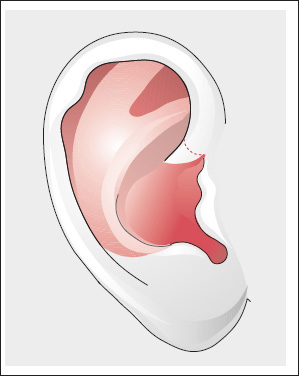

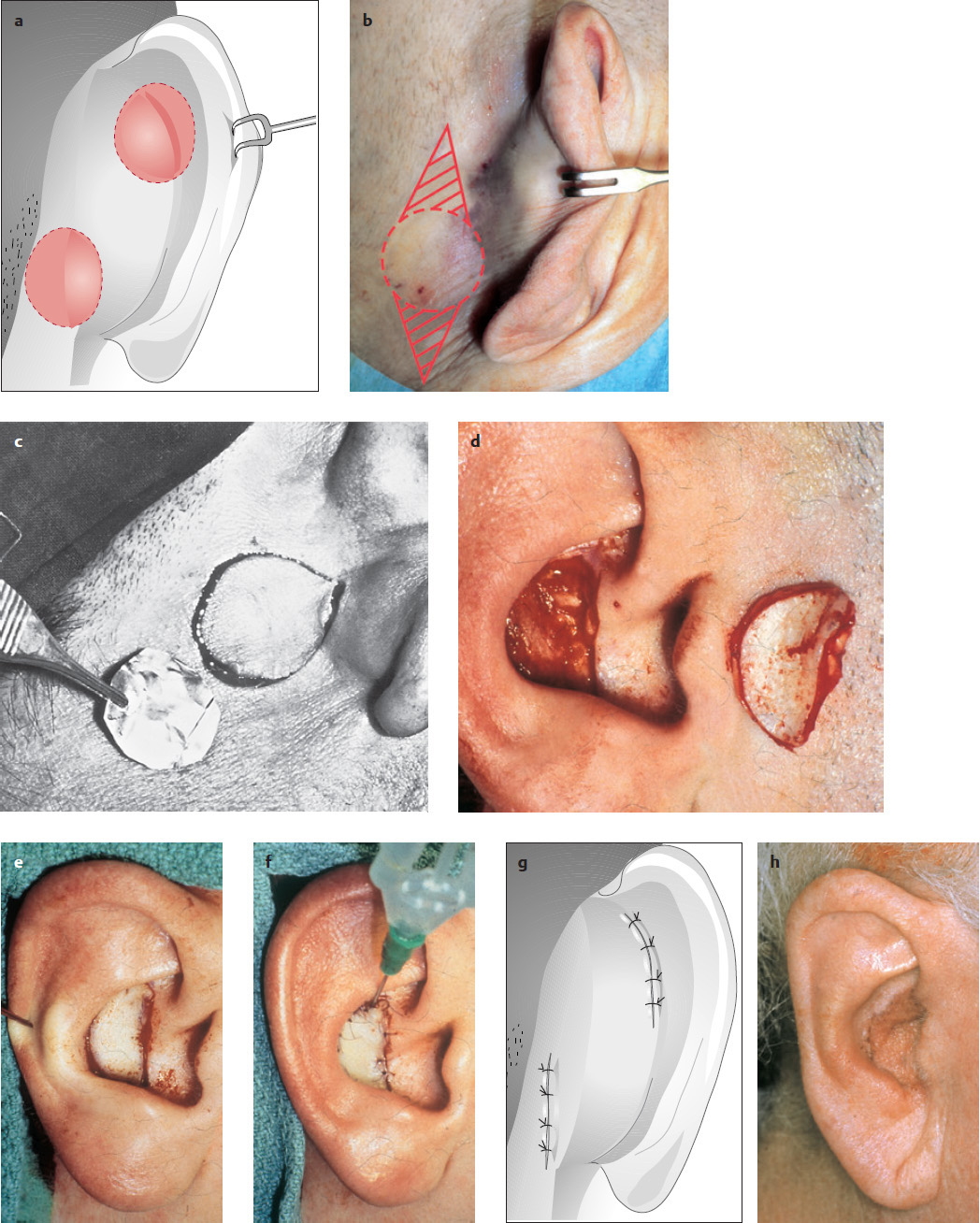

Conchal Defects

Reconstruction with a Full-thickness Skin Graft

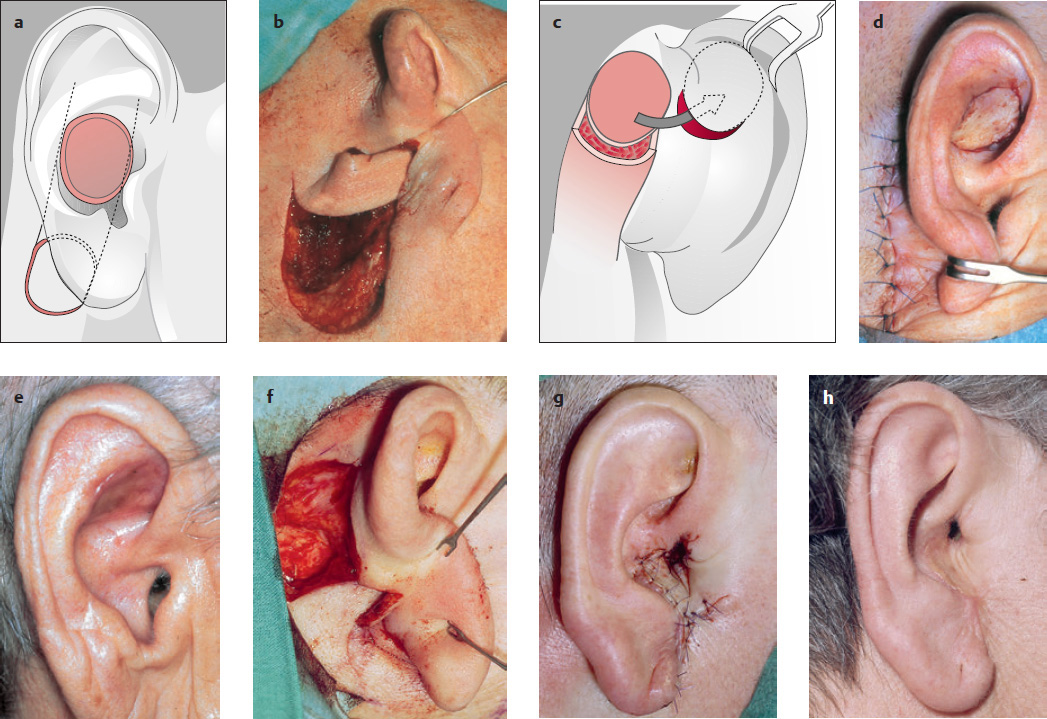

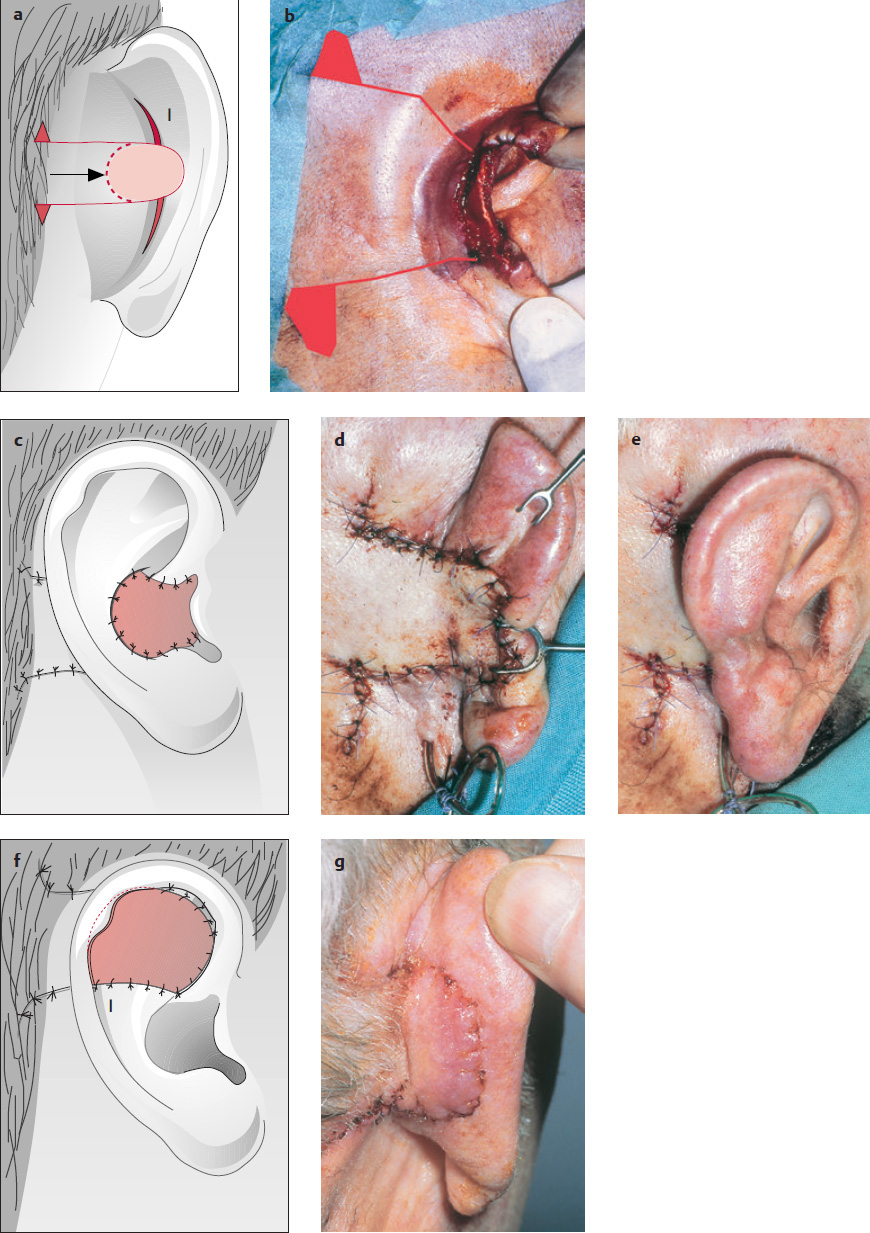

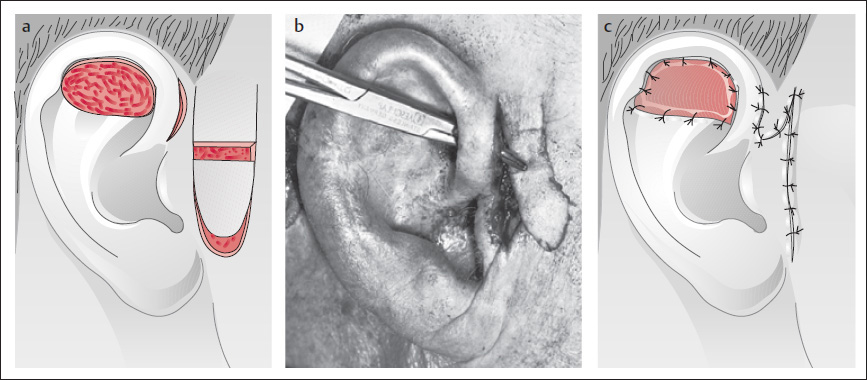

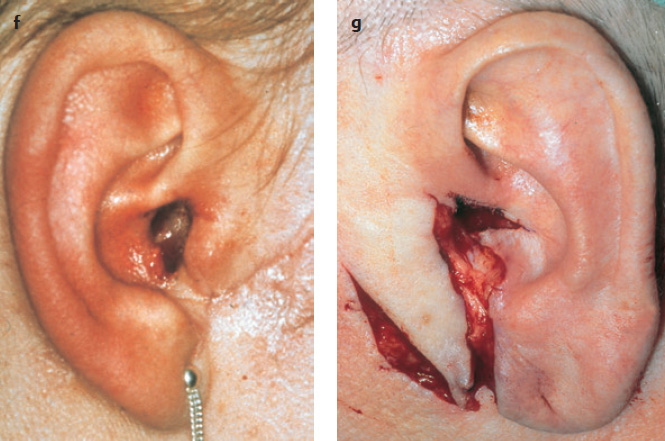

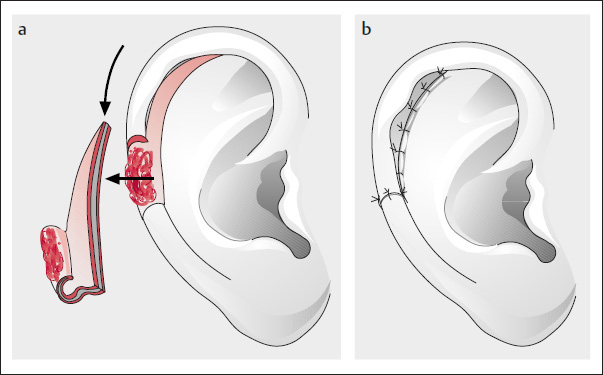

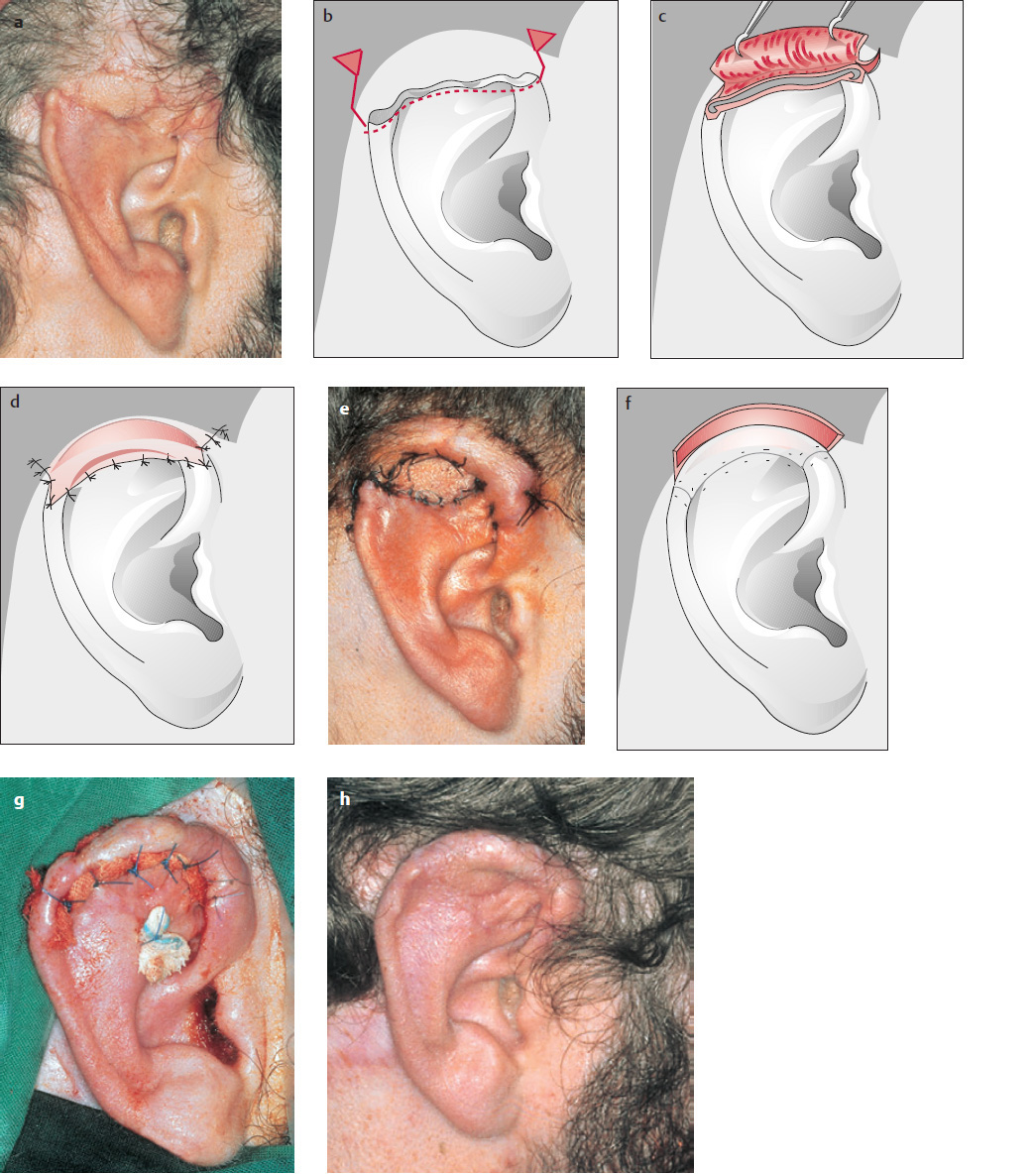

( Fig. 10.3 )

Since large parts of the concha adjoin the mastoid region, full-thickness skin is an option for reconstructing the concha. Reconstruction with a full-thickness skin graft is shown in Fig. 10.3a–h .

Transposition Flap and U-shaped Advancement

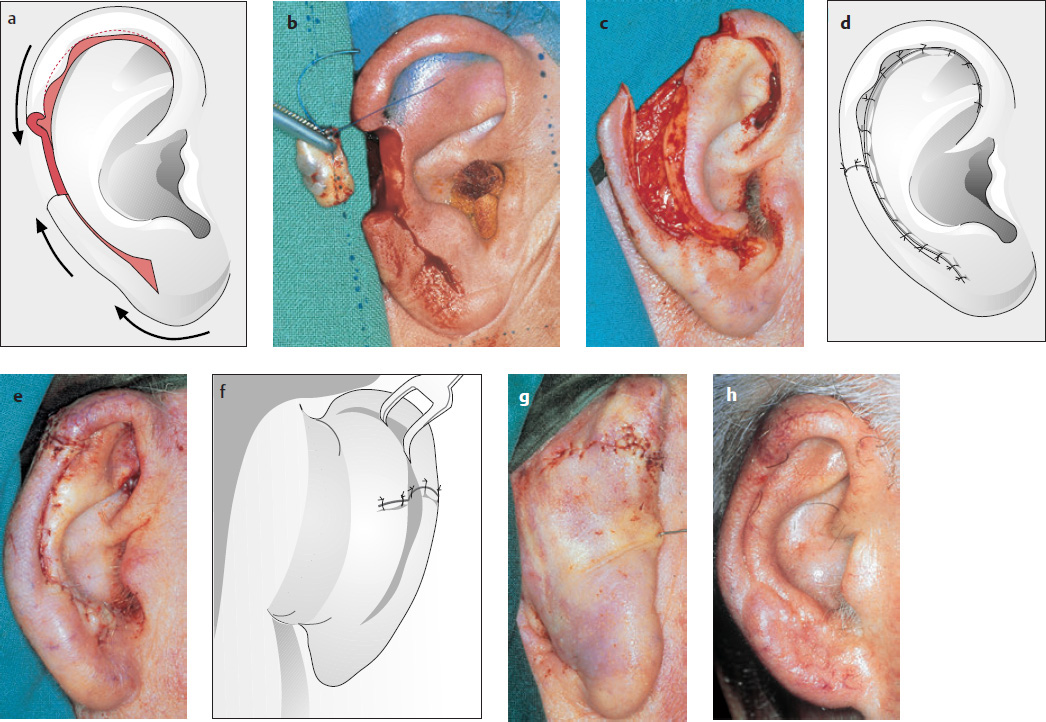

( Fig. 10.4 )

When the defects are situated somewhat higher, and extend into the antihelix, or into the auditory canal, it is possible to use superiorly or inferiorly based transposition flaps, de-epithelialized at the site that comes to lie beneath the tunnel when passed anteriorly (pull-through technique; Fig. 10.4c ).

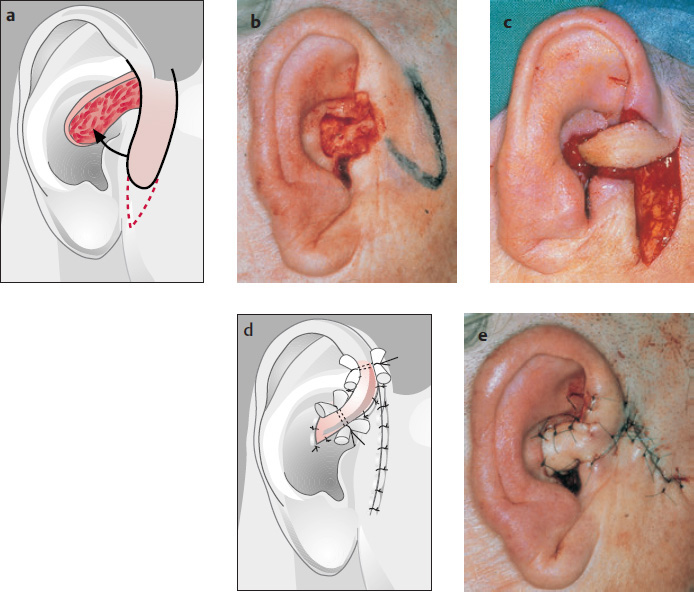

Reconstruction with Island Flaps

( Figs. 10.5–10.7 )

“True” island flaps are flaps that are supplied by an artery but disconnected from the surrounding tissue (Kazanjian 1958; Weerda 1999b, 2004). The following techniques are used:

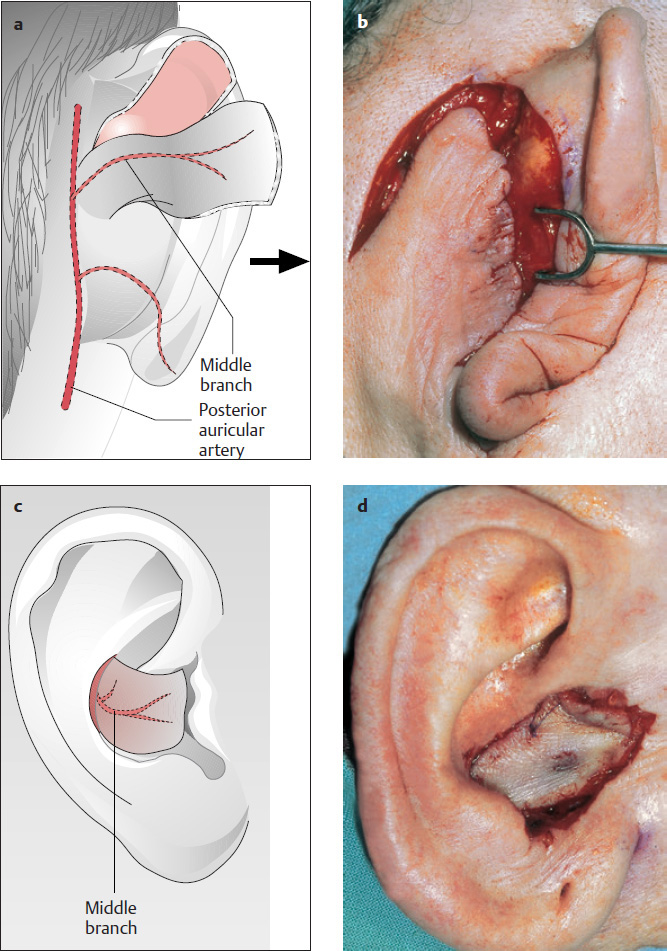

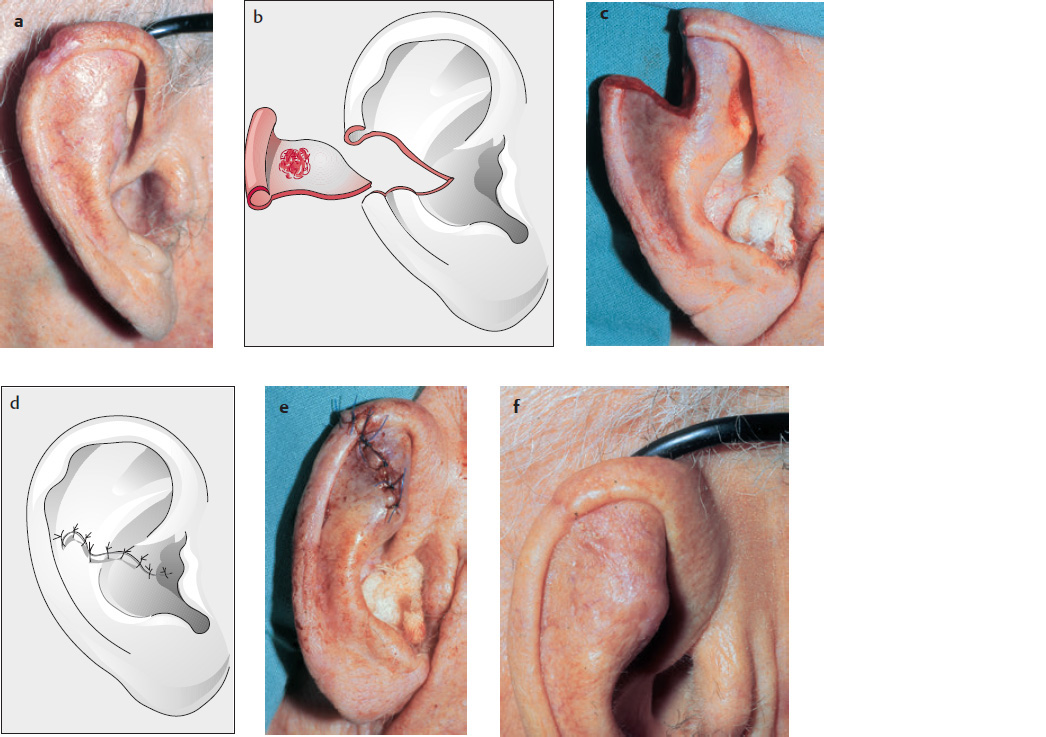

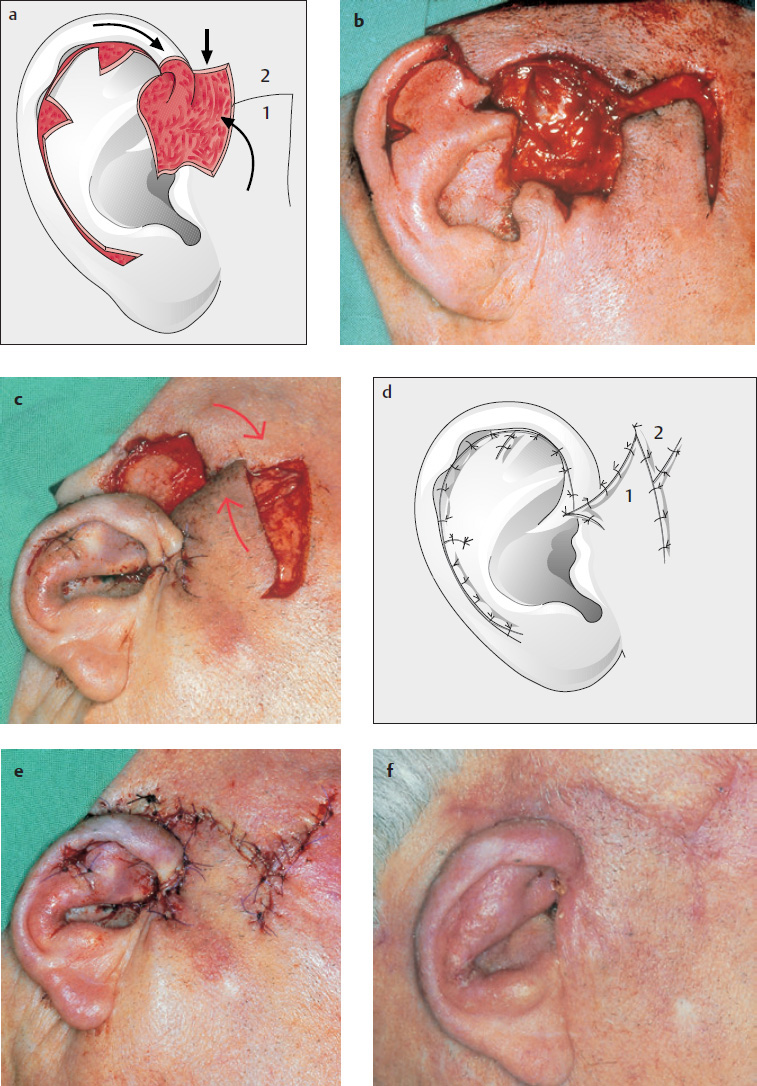

Reconstruction of a two-layer defect using a myocutaneous island flap based posteriorly on the posterior auricular artery (Krespi et al. 1983; Weerda and Siegert 1999a; Weerda 2001; Fig. 10.5a–f ).

Zong-ji and Chao (1990) also use an island flap based posteriorly on the posterior auricular artery.

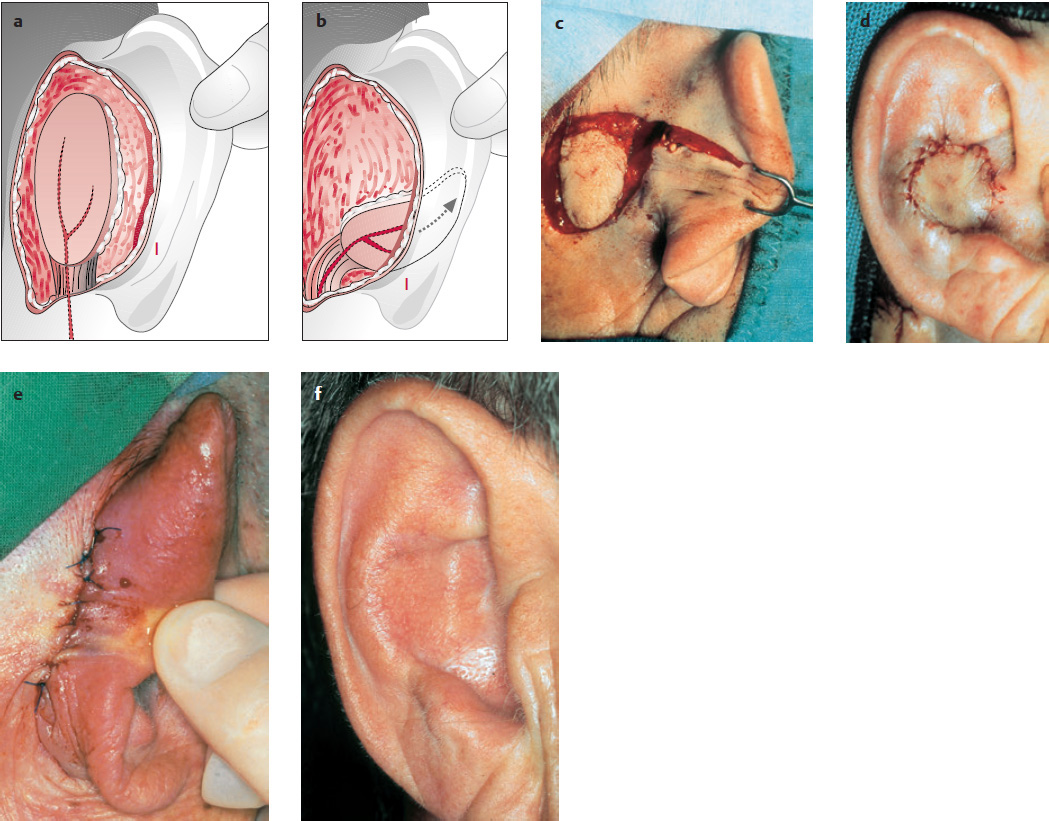

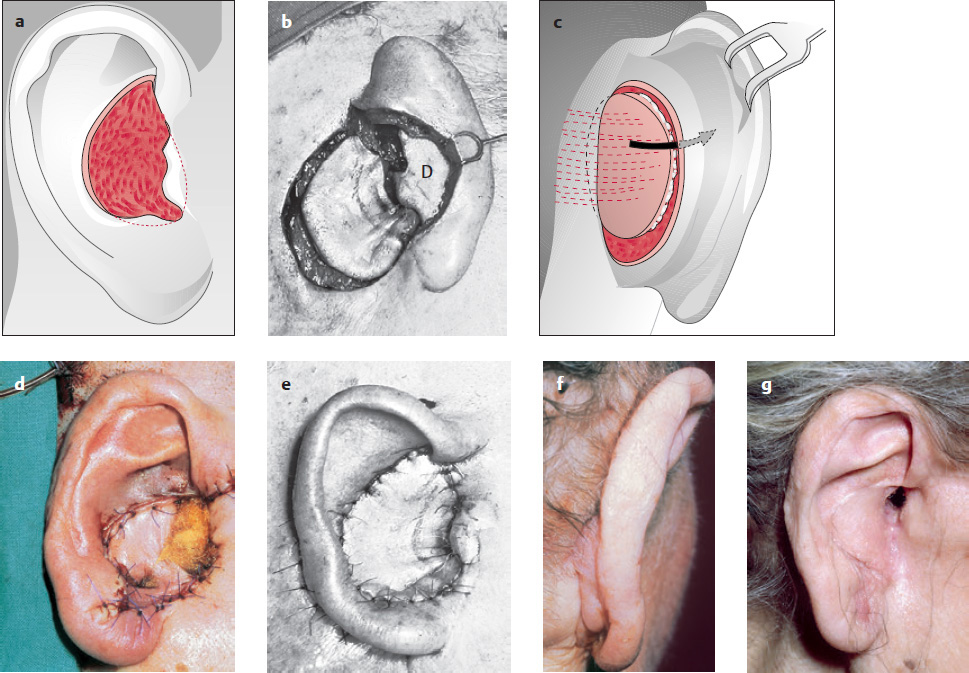

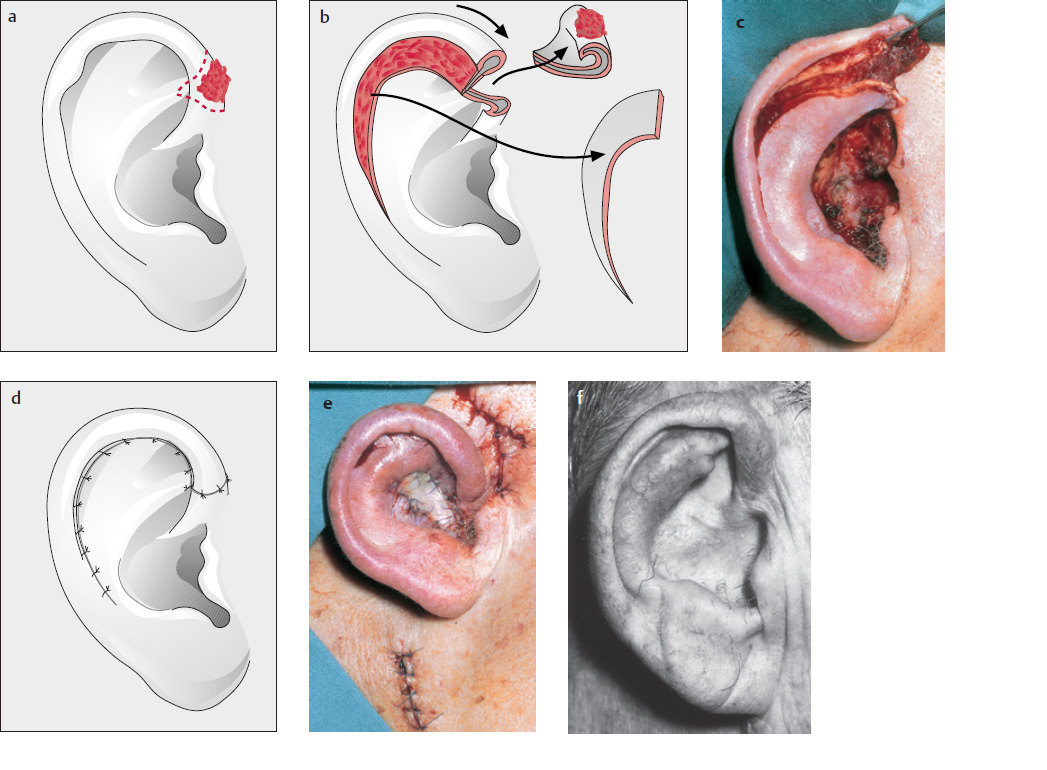

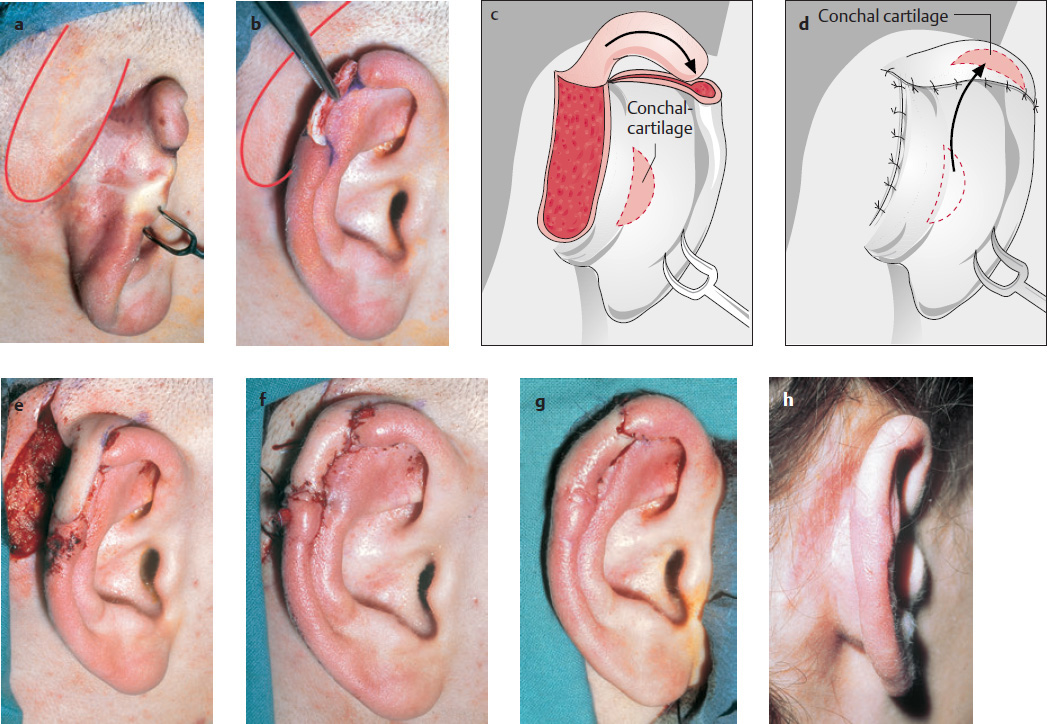

Large island flap based on a dermal pedicle (as described by Masson 1972; Renard 1981; Koopmann and Coulthard 1982; Jackson 1985b; Fig. 10.6a–g )

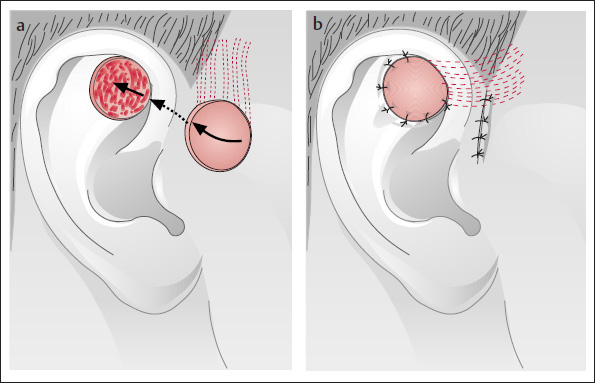

Island flap as described by Park et al. (1988; Fig. 10.7a, b ).

Park and Chung (1989) have pointed out that the direction of blood flow is reversed after the flap is inset. The donor site is covered with a split-thickness or full-thickness skin graft.

Defects of the Antihelix and Combined Central Defects (Figs. 10.8 and 10.9)

In particular, posterior transposition flaps and island flaps based posteriorly on a dermal pedicle or on the posterior auricular artery can be used (see Figs. 10.4–10.6 ) for the reconstruction of defects in the antihelical region ( Fig. 10.8a, b ) or for more extensive central defects (combined central defects; Fig. 10.9 ), as previously described (see pp. 138, 139).

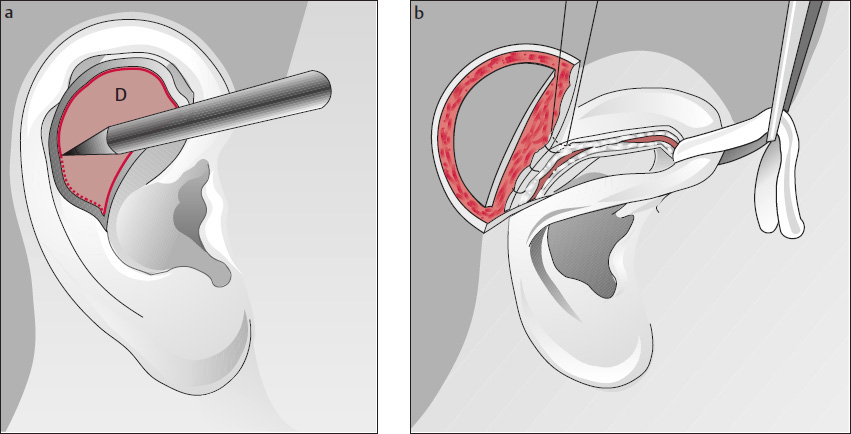

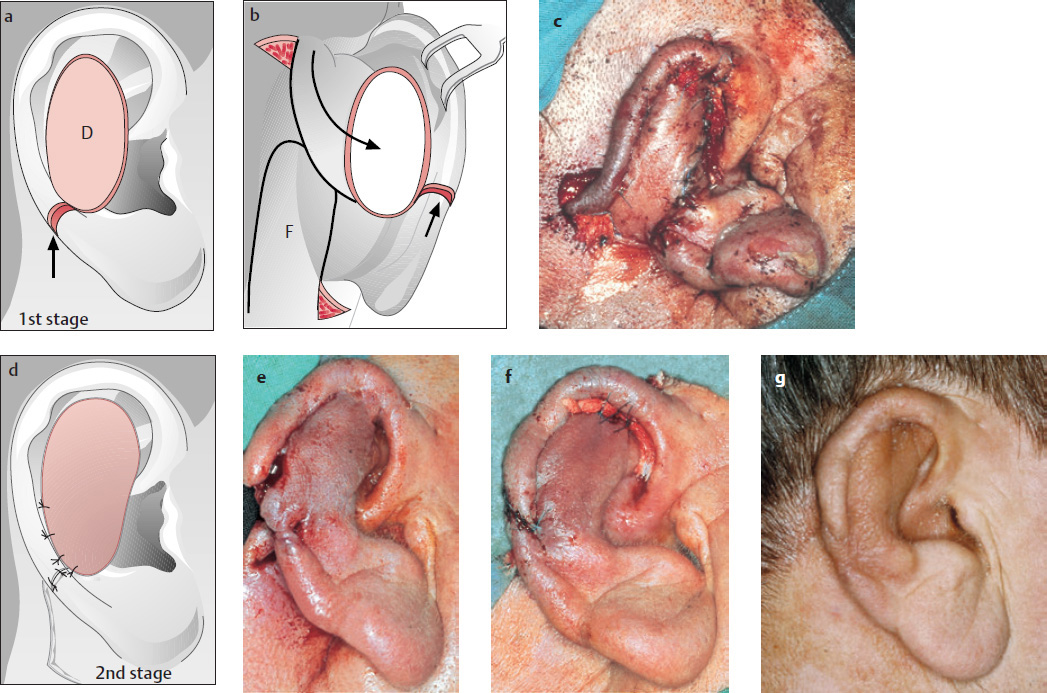

Converse and Brent’s (1977) Three-stage Reconstruction of Full-Thickness Defects of the Antihelix

( Fig. 10.10 )

The flap can be extended onto the postauricular skin to cover large defects of the concha and antihelix (Jackson 1985b; see Fig. 10.6 ).

Superiorly or Inferiorly Based Transposition Flap

( Fig. 10.11 ; see also Fig. 10.4 )

Stage I:

A large, superiorly based, retroauricular transposition flap is raised, which, depending on the size of the defect, can be extended to the neck ( Fig. 10.11a ). The flap is de-epithelialized at the site where it is brought through, and then inset ( Fig. 10.11c ). Behind the ear, the flap may also be used to cover the postauricular defect (Weerda 1994b; see Fig. 10.4 ).

Stage II:

The flap pedicle can be divided after 3 weeks. The remnants of the pedicle are thinned out and incorporated into the mastoid surface, and the wound is closed in two layers. Full-thickness defects that are not too large can be covered on their postauricular surface with a split-thickness or full-thickness skin graft. Double rotation (see also Fig. 10.88 or transposition–rotation flaps (see also Figs. 10.61, 10.86 and 10.87 ) can be used for the single-stage resurfacing of particularly large central defects (see also pp. 137–141).

U-shaped Advancement Flap of Gingrass and Pickrell (1968)

( Fig. 10.12 )

After ~3 weeks, the pedicle is divided and the post-auricular wound closed. This flap is also suitable for defects in the region of the posterior auditory canal and the antitragus.

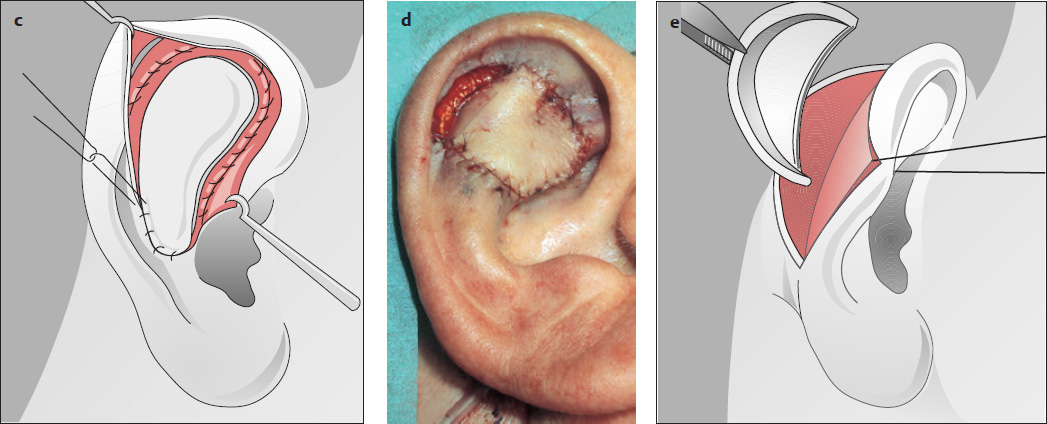

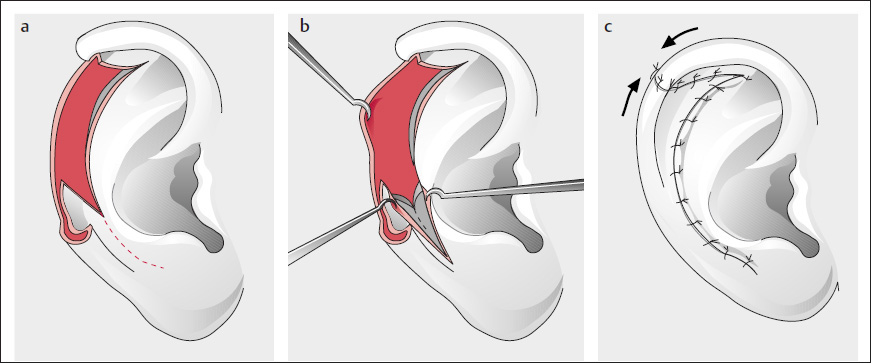

Weerda’s Reconstruction with a Transposition Flap and Temporary Repositioning of the Helix

( Fig. 10.13 ; Weerda 1984)

Weerda’s Bilobed Flap as a Transposition–Rotation Flap

( Fig. 10.14 ; Weerda and Münker 1981)

As will later be described in detail, a bilobed flap ( Fig. 10.14b, c ) can also be used for larger, full-thickness antihelix–conchal defects ( Fig. 10.14a ). The flap is de-epithelialized below the helix and supported with cartilage ( Fig. 10.14d ).

Preauricular Flaps

Many authors use preauricular flaps for smaller central defects.

Tebbetts’ (1982) Superiorly Based, Preauricular Flap for the Triangular Fossa

( Fig. 10.16 )

Mellette’s (1991) Preauricular Flap Based Superiorly on the Helical Crus

( Fig. 10.17 )

This technique is also suitable for reconstruction of the helical crus. The flap is pedicled on the ascending limb of the helical crus and can be used to cover defects in the region of the concha and the entrance to the auditory canal. Sometimes, improvements can be made to the helical crus in a second stage (Weerda and Siegert 1999a, 2001).

Inferiorly Based Preauricular Flap

( Fig. 10.19 )

An inferiorly based preauricular flap can be used for covering the intertragic notch and the inferior concha, for the posterior surface of the tragus and the lateral auditory canal.

Peripheral Defects

( Fig. 10.20 )

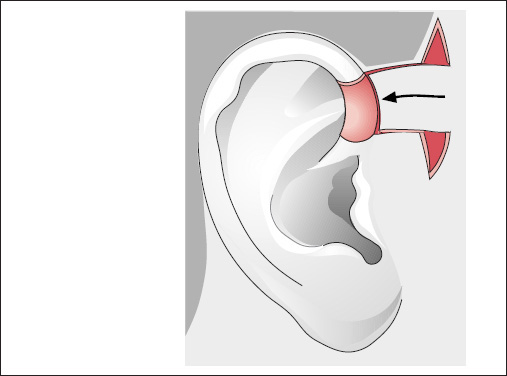

Peripheral defects refer in particular to defects located on the helix ( Fig. 10.20 ; see Fig. 10.1 ).

Helix Reconstruction with Auricular Reduction

The techniques described for reduction of the auricle during correction of macrotia are very well suited for treating defects of the helix secondary to tumor excision or trauma (see, for example, Di Martino 1856, as cited in Joseph 1931; Trendelenburg 1886, as cited in Joseph 1931; Cocheril 1894, as cited in Tanzer et al. 1977; Joseph 1896, 1931. If the age and general condition of the patient allow it, some of these operations can be performed under local anesthesia, on an outpatient basis.

Recommended Defect Reconstruction

Wedge excisions and reconstruction with advancement of the helix can be recommended.

Simple Wedge Excisions

( Fig. 10.21 )

For small helical lesions or small defects, a simple extension of the wound in the form of a wedge excision is enough to achieve an adequately pleasing esthetic result (see Fig. 5.41 ; p. 55).

Wedge Excision and Burow’s Triangles

( Fig. 10.22a–j )

Because irregularities in form and contour can result from simple wedge excision, Trendelenburg (1886, as cited in Joseph 1931) recommended the removal of Burow’s triangles. This procedure has since been modified in many ways (see for example Trendelenburg 1886, as cited in Joseph 1931; Joseph 1896; Goldstein 1908; Lexer 1933). Whenever possible, we place the Burow’s triangles in the scapha ( Fig. 10.22e ) or along the border between the concha and its transition to the antihelix ( Fig. 10.22a ; Converse and Brent 1977).

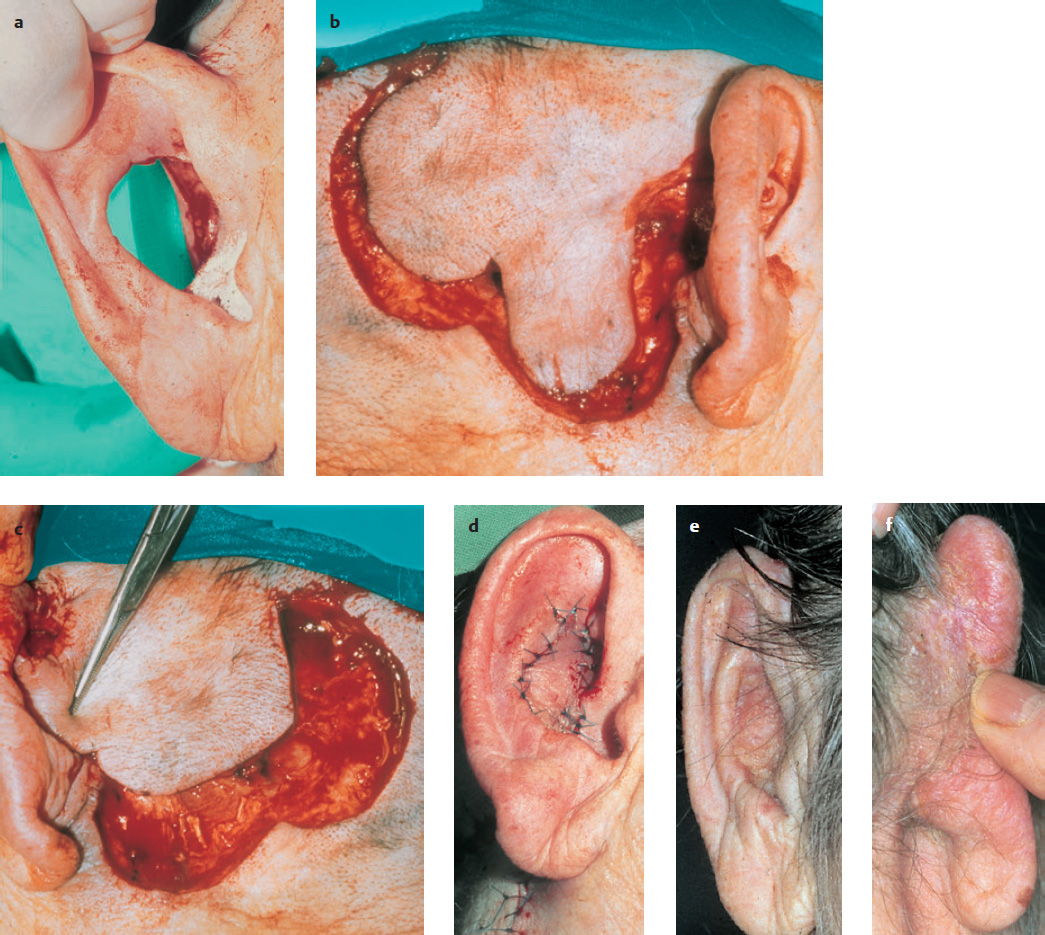

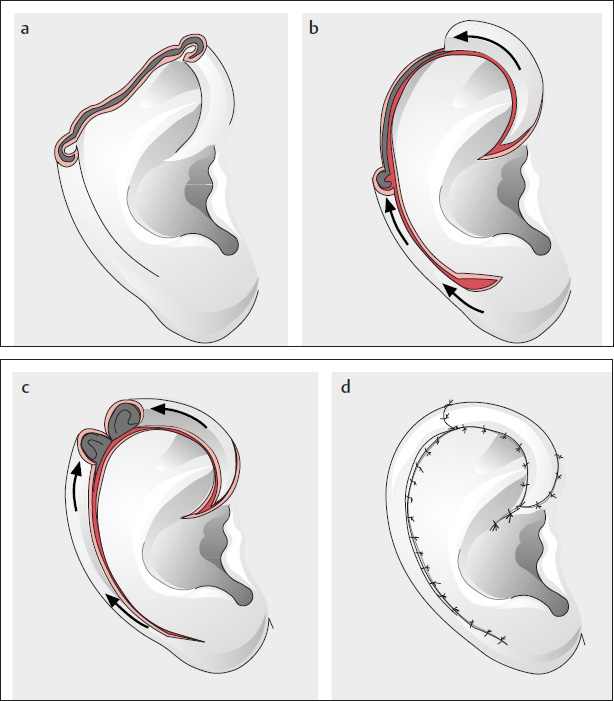

Gersuny’s (1903) Technique of Defect Closure by Transposition of the Helix

( Fig. 10.23 )

Gersuny performed a full-thickness crescent-shaped excision in the scapha of a female patient who had sustained a helical lesion, and transposed the helix into the resultant defect ( Fig. 10.23a, b ). This elegant method has been modified in several different ways (see Figs. 10.24, 10.29, 10.30 ).

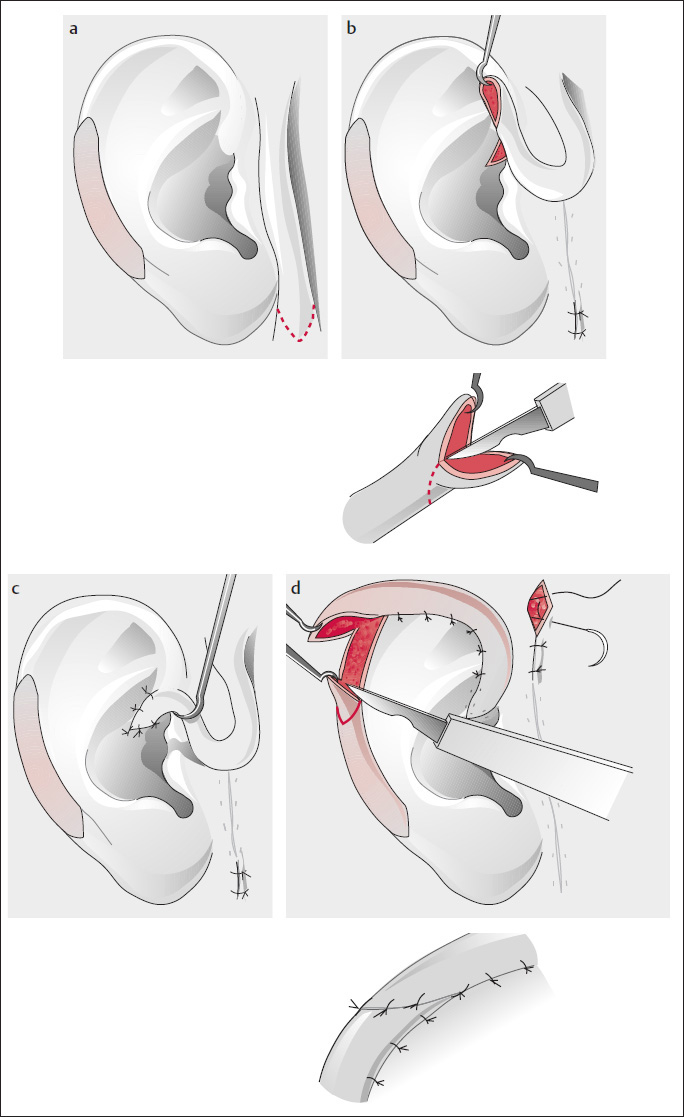

Modification of the Gersuny Technique by Weerda and Zöllner (1986)

( Fig. 10.24 )

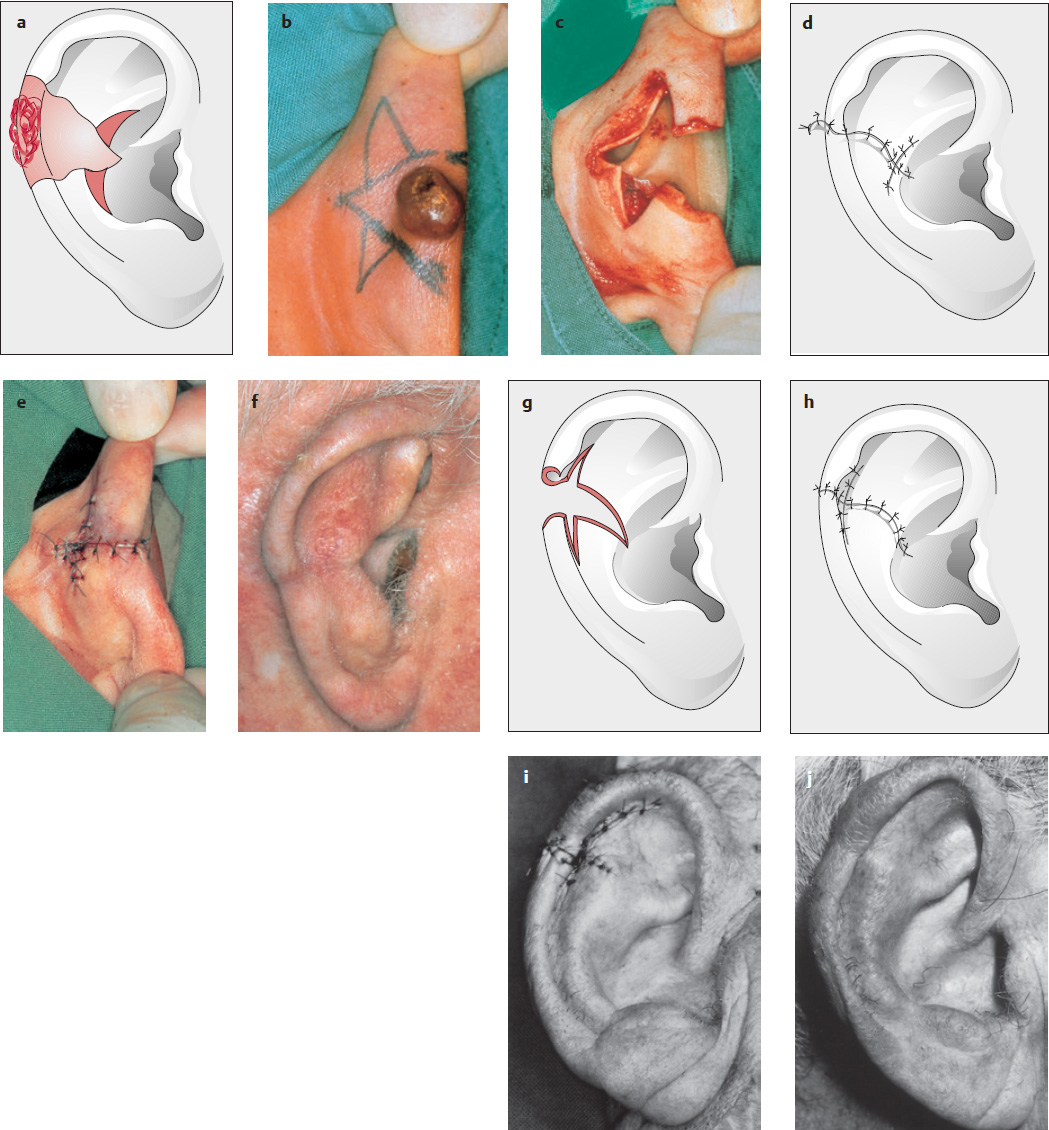

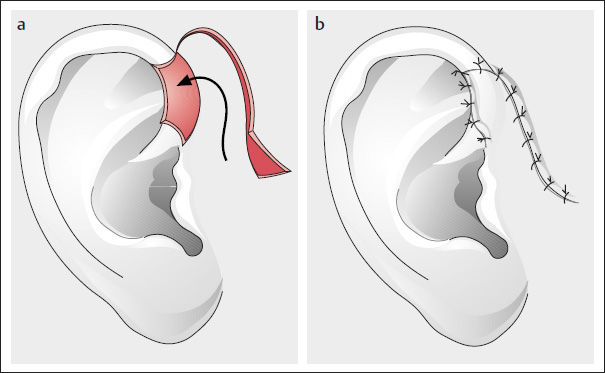

Similar to Antia and Buch (1967) and Antia (1974), and in contrast to Gersuny (1903; see Fig. 10.23 ), we made only a two-layer, crescent-shaped excision in the scapha after excision of the tumor and dissected the skin on the posterior auricular surface ( Fig. 10.24b, d, e ).

Antia and Buch’s Modification with Mobilization of the Helical Crus

( Fig. 10.25 ; Antia and Buch 1967, Antia 1974)

In a modification for larger defects, the helical crus was additionally incised (it remains pedicled posteriorly and superiorly).

Lexer’s (1933) Modification

( Fig. 10.26 )

This modification is a full-thickness crescent-shaped excision from the scaphal and antihelical margin after excision of the tumor. The postauricular skin is excised slightly higher and then elevated. The defects are slid into each other, and the auricle is reduced by closing cartilage and skin ( Fig. 10.26b ; Ginestet et al. 1967).

Argamaso and Lewin’s (1968) Technique of Ear Reduction and Defect Reconstruction

( Fig. 10.27 )

For smaller defects, a Z-plasty is performed by transposing the inferior portion into the superior segment ( Fig. 10.27c ) in the form of a chondrocutaneous flap ( Fig. 10.27a, b ).

Meyer and Sieber’s (1973) Modification of the Technique

( Fig. 10.28 )

The concha or the preauricular defect can be treated together with tumors of the ascending helix ( Fig. 10.28a–d ; Argamaso 1989).

Tenta and Keyes’ (1981) Excision of the Triangular Fossa with Reduction of the Auricle

( Fig. 10.29 )

After full-thickness excision ( Fig. 10.29a ), the helix is used to cover the defect ( Fig. 10.29c ), as with Gersuny’s technique (1903); Fig. 10.29b ; see also Figs. 10.30 and 10.42 ).

Critique:

Here too, techniques that preserve the size of the auricle should usually take preference.

The techniques of reconstruction described here for conchal defects and defects of the antihelix can also be used for larger combined defects of the concha and antihelix (see also p. 137ff.).

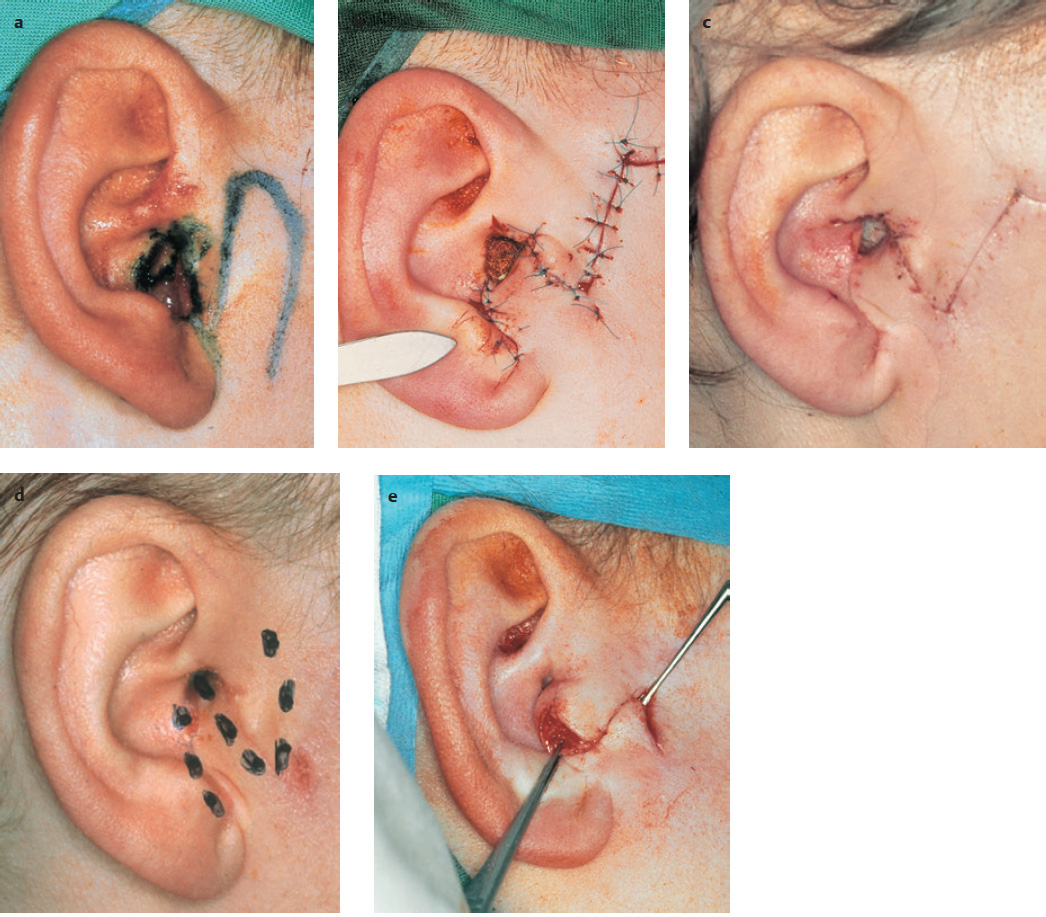

Weerda and Zöllner’s (1986) Technique for Defects of the Helical Crus and Preauricular Region

( Fig. 10.30 ; Weerda and Zöllner 1986; Weerda 1988d; see also Fig. 10.43 )

The entire helix can be rotated anteriorly to treat tumors in the region of the anterior ascending helix, the helical crus, and the preauricular region, with the preauricular defect subsequently being covered by a Dufourmentel rhomboid flap (see also p. 26).

Nonrecommended Methods of Defect Reconstruction

Pegram and Peterson’s (1956) Reconstruction with a Free Full-Thickness Composite Graft from the Contralateral Ear

(Pegram and Peterson 1956; see also the section “Middle third of the auricle”, p. 168).

Even Körte (1905) and Lexer (1910) had previously used composite grafts for reconstruction of the ear. Similar techniques to reconstruct partial defects are described by Day (1921), Melchior-Breslau (1928 as cited in Joseph 1931), Wachsberger (1947), Pegram and Peterson (1956), Nagel (1972), Brent (1975), and Converse and Brent (1977). The margins of the defect are freshened, or the tumor excised; a wedge-shaped, full-thickness composite graft of half the defect size is removed from the contralateral ear and inset into the defect; the cartilage is adapted with a 5-0 braided suture; and the skin is closed with a 6-0 or 7-0 monofilament suture. The wedge defect of the contralateral side is closed in a similar fashion.

Critique:

These techniques may be suitable, if at all, for smaller defects (see Fig. 3.16 ) because adequate nutrition of larger, freely transplanted composite grafts cannot be guaranteed. We see a high rate of graft loss, especially when this technique is performed by less experienced surgeons (see Weerda 2007, pp. 32–40, 57).

Helix Reconstruction without Auricular Reduction

Since the defects (see Fig. 10.21 ) frequently involve more than one region, reference will be made in the text and in the figure legends to similar reconstructions in other chapters.

Anterior Defects: Helical Crus and Ascending Helix ( Figs. 10.31 and 10.32 )

The ascending helix, as well as the helical crus, can be reconstructed with a small U-shaped advancement flap ( Fig. 10.31 ), a rotation flap ( Fig. 10.32a, b ), or a preauricular, superiorly or inferiorly based transposition flap ( Fig. 10.32 ).

Superior and Middle Thirds of the Helix

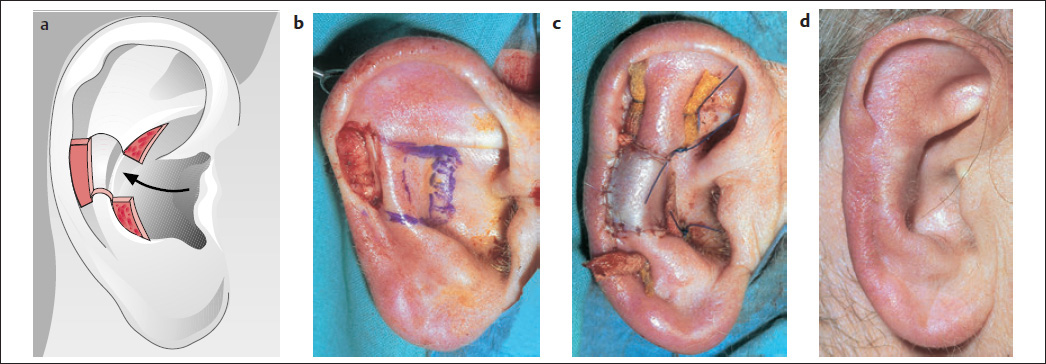

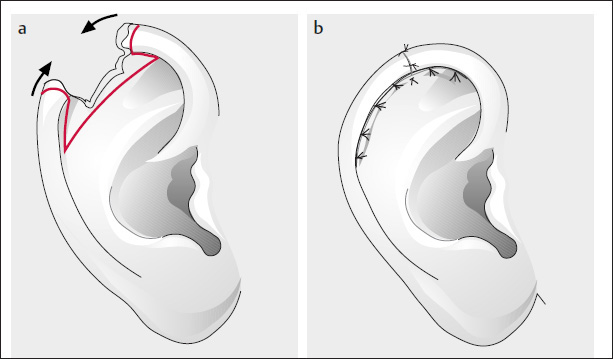

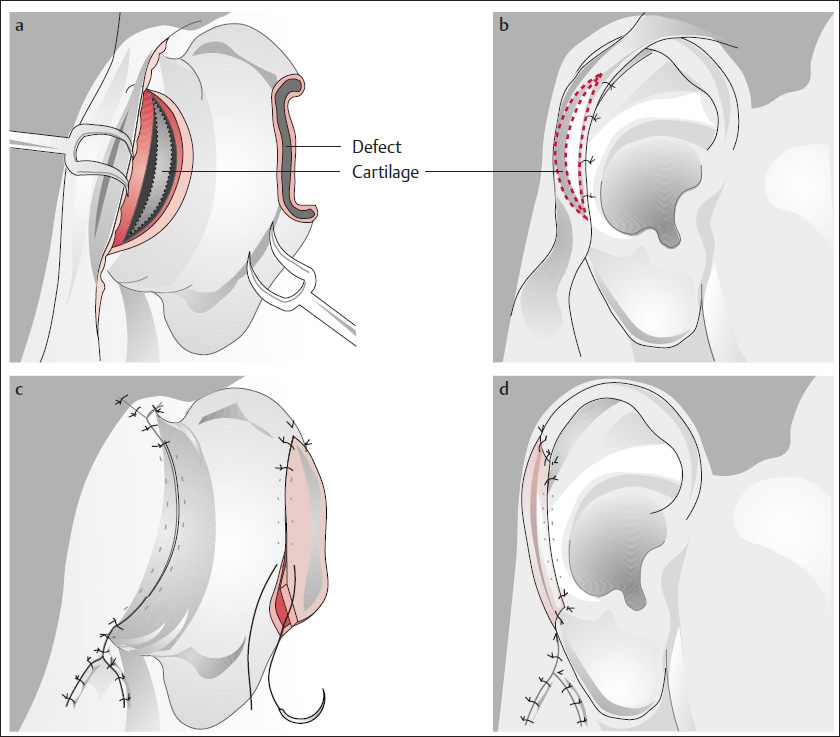

Superiorly Based Postauricular Transposition Flap

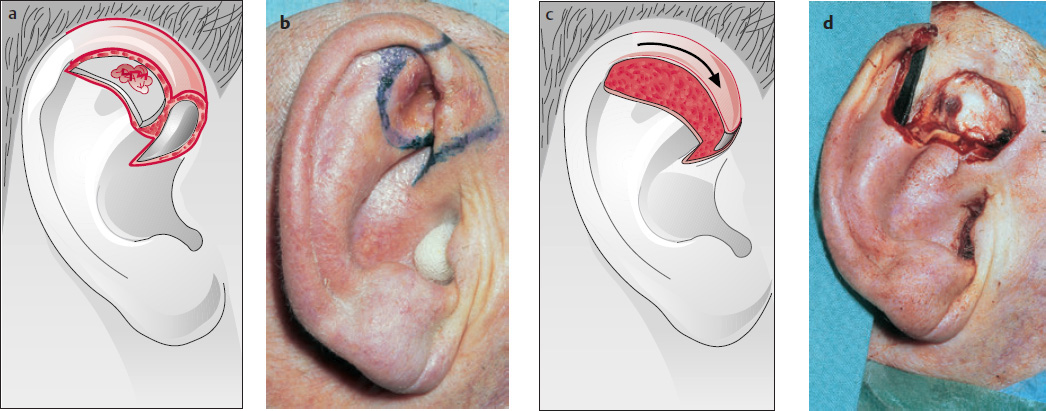

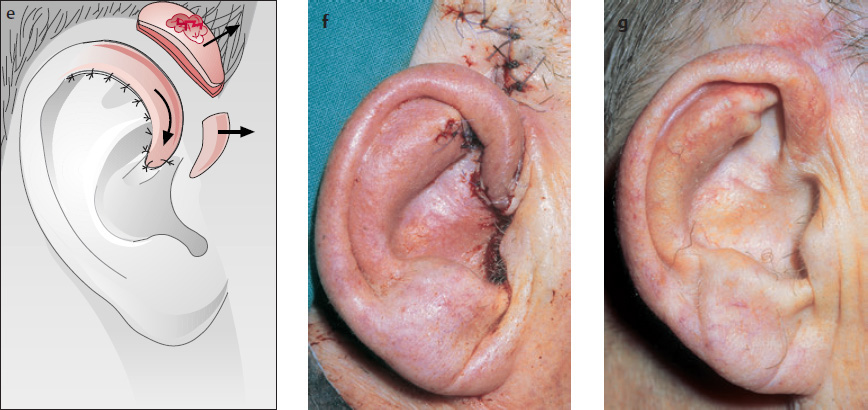

( Fig. 10.33 ; Weerda and Siegert 1999a; Weerda 2007)

A superiorly based posterior flap is raised in the sulcus, patterned from a template made from aluminum foil (Pennisi et al. 1965; Tebbetts 1982; Mellette 1991; Weerda and Siegert 1999a; Weerda 2001) and inserted over a cartilaginous support ( Fig. 10.33a–f . After resection of the pedicle in a second stage, we can obtain a good result ( Fig. 10.33d, g, h ).

Preauricular Transposition Flap

( Fig. 10.34a–c )

As with the posterior flap, a patterned preauricular flap is used to reconstruct the superior helix.

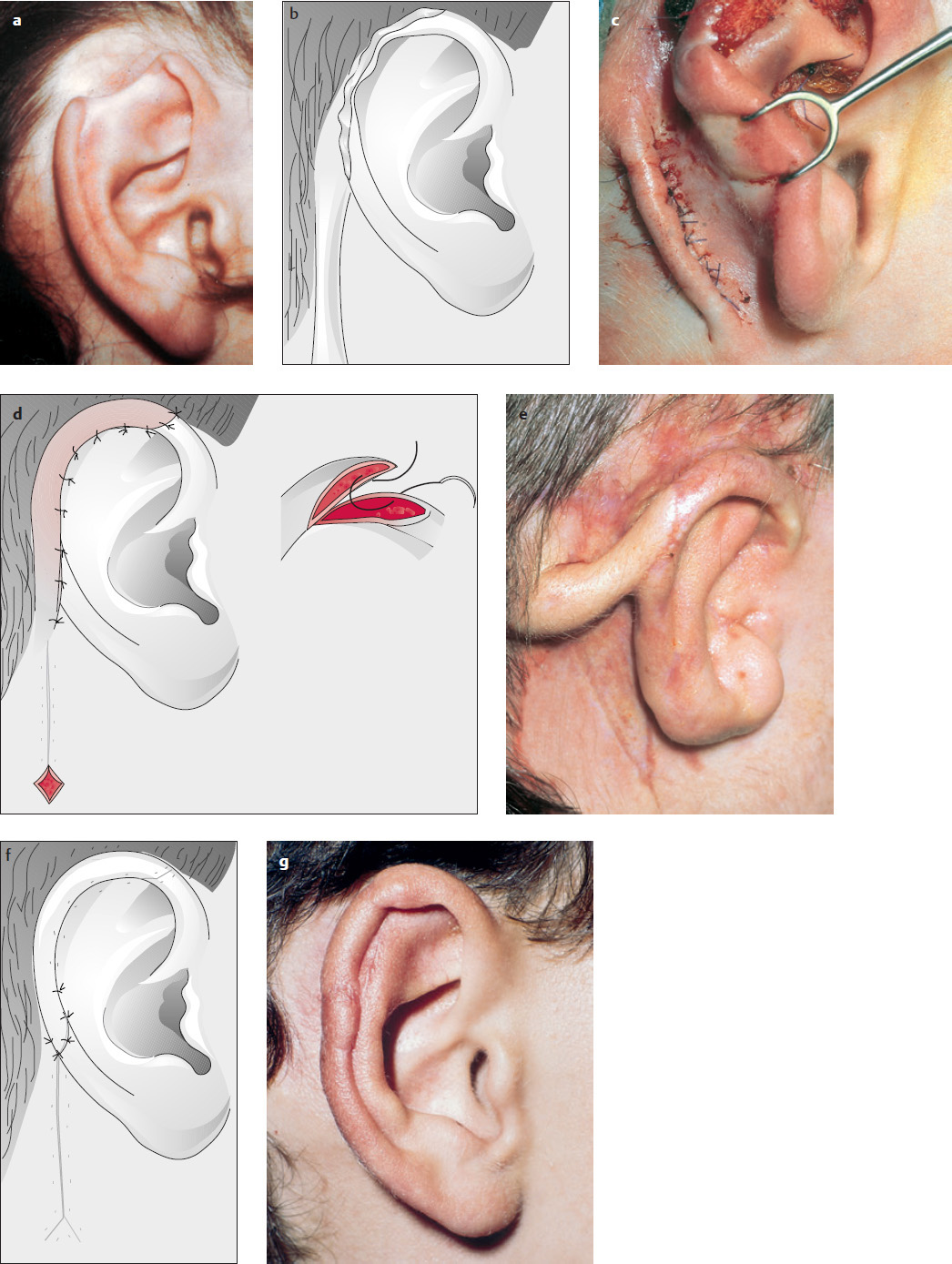

Retroauricular Flap of Smith (1917)

( Fig. 10.35a–h )

The upper (middle) third of the auricular helix is reconstructed with a broad-based, superiorly pedicled retroauricular flap (see Fig. 10.57 ).

Tube-Pedicled Flap

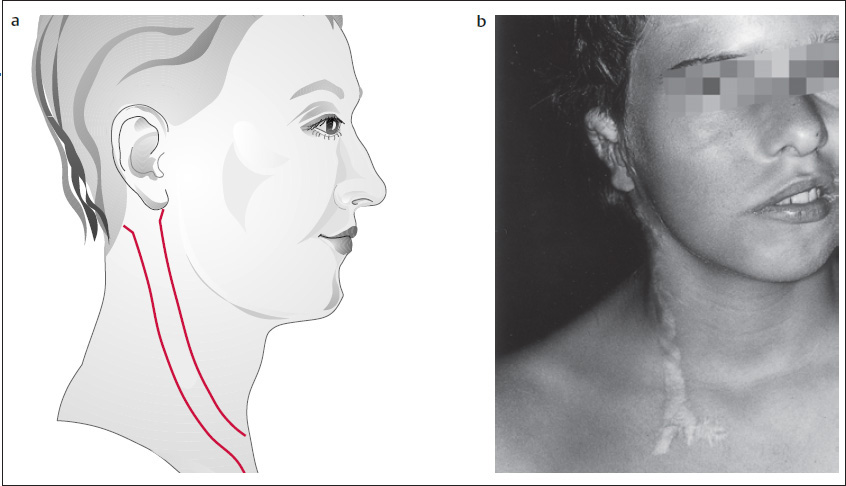

( Fig. 10.36 )

Pre-, post-, and retroauricular tube-pedicled flaps can be employed for all regions of the helix. Tube-pedicled flaps of the neck ( Fig. 10.36a ; Pierce 1925; Hamblen-Thomas 1938; McNichol 1950; Converse 1958; Cosman and Crikelair 1966; Pitanguy and Flemming 1976; Davis 1987) can usually no longer be recommended, given that they produce conspicuous hypertrophic scars in the neck region ( Fig. 10.36b ). “Migrating” flaps of the supraclavicular region are better.

Defects of the upper, middle, or lower third of the helix can be reconstructed with a tunneled (bipedicle) or tubed pedicle flap that is raised in the sulcus and initially based superiorly and inferiorly (see Fig. 10.37 ; Streit 1914; Troha et al. 1990; Dujon and Bowditch 1995).

Recommended Techniques for Defect Reconstruction

Tube-Pedicled Flap for the Superior Helix

( Fig. 10.37 ; see also, Fig. 10.34 )

The tube-pedicled fap for the superior helix can also be used as a tubed bipedicle (tunneled) fap (see also Fig. 10.38 ).

Tubed Bipedicle Flap for Defects of the Superior and Middle Thirds

( Figs. 10.38 and 10.39 )

Three-stage Reconstruction of a Defect of the Middle Third with a Tube-Pedicled Flap

( Fig. 10.39 ; Steffanoff 1948; Converse and Brent 1977; Weerda and Siegert 1999a; Weerda 2001)

Unlike reconstruction with a tunneled flap (see Fig. 10.37a ), the tube-pedicled flap is first raised and rolled into a tube ( Fig. 10.39b, c ). If there is not sufficient skin for closure, we use split skin for coverage, or wrap the exposed tube-pedicled flap with silicone foil (see also Fig. 10.33b ).

Converse and Brent’s (1977) Reconstruction with a Preauricular Tube-Pedicled Flap

( Fig. 10.39 )

Similar to the flap previously described, a preauricular tube-pedicled flap can be raised for defects of the anterior and superior helix as well as for the helical crus (Berson 1948; Converse 1958; Converse and Brent 1977).

Inferior Helix

These reconstructions are similar to those of the superior and middle thirds of the helix; further reconstructions are discussed under “Lower partial reconstructions” (see p. 174).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree