Technical Tips for Avoiding Complications in TRAM Flap Breast Reconstruction

Since its introduction in 1981, the transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous (TRAM) flap1 has become the gold standard in breast reconstruction worldwide. This procedure provides the reconstructive surgeon with the ability to create a natural-appearing permanent breast mound using the patient’s own tissue, which can simulate the appearance of almost any opposite breast. Indeed, the TRAM flap is a great operation. However, it is a demanding procedure for both the patient and the surgeon. Obtaining consistently good aesthetic results requires careful preoperative planning and technical proficiency. Despite these efforts, TRAM flap breast reconstruction can be compromised by a multiplicity of factors, including vascular insufficiency in the flap or ischemia of the native breast skin flaps, errors in aesthetic planning and judgment, and errors in technique while reconstructing the new breast.

As discussed later in this chapter, consistently excellent outcomes in reconstructive and aesthetic plastic surgery are the result of intense preoperative study. The most important factors for achieving consistent success with TRAM flap breast reconstruction results are having an individualized artistic plan and using careful operative technique with attention to detail, in that order. I believe that the importance of planning in breast reconstruction (and in virtually all plastic surgery procedures for that matter) cannot be overstated, and for TRAM flap breast reconstruction the adage “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” is very applicable.

The goal of TRAM flap breast reconstruction is to reconstruct the best possible breast while keeping the complication rate to an absolute minimum. Toward this end there are two important considerations: procedure selection,2 or choosing the appropriate TRAM flap procedure type for a given patient, and patient selection, or carefully analyzing individual patient comorbidities to select only appropriate candidates for the procedure.3 This chapter emphasizes these concepts and presents what I believe to be important points of surgical technique.

Postoperative breast asymmetry following TRAM flap breast reconstruction is not uncommon. The etiology of suboptimal outcomes is directly related to either errors in planning or vascular compromise in the flap, producing fat necrosis or various degrees of flap loss. Errors in planning may be due to a number of factors (Table 7-1),

including skin replacement miscalculations, breast volume discrepancies, suboptimal flap inset positioning, and inframammary (IM) fold asymmetries. More significant suboptimal outcomes are usually secondary to vascular compromise in the flap. This can result in fat necrosis or various degrees of flap loss, ranging from minor to major. Likewise, complications in the donor site region are also not uncommon. These relate to skin necrosis in the lower abdominal incision area, postoperative seroma accumulation, and eccentricity and/or partial necrosis of the umbilicus, but more significantly they relate to contour deformity both in terms of bulges and frank hernia in the lower abdominal region, both of which can be quite disturbing or debilitating for the patient.

including skin replacement miscalculations, breast volume discrepancies, suboptimal flap inset positioning, and inframammary (IM) fold asymmetries. More significant suboptimal outcomes are usually secondary to vascular compromise in the flap. This can result in fat necrosis or various degrees of flap loss, ranging from minor to major. Likewise, complications in the donor site region are also not uncommon. These relate to skin necrosis in the lower abdominal incision area, postoperative seroma accumulation, and eccentricity and/or partial necrosis of the umbilicus, but more significantly they relate to contour deformity both in terms of bulges and frank hernia in the lower abdominal region, both of which can be quite disturbing or debilitating for the patient.

TABLE 7-1 Suboptimal Outcomes Following TRAM Flap Breast Reconstruction Related to Errors in Planning | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Unfortunately, despite careful patient selection and appropriate procedure selection, as well as consistent surgical technique, complications do occur that can compromise the outcome of a TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Chapter 8 addresses the common complications observed after TRAM flap breast reconstruction and presents my approach to addressing each of these.

A considerable amount of text in this chapter is devoted to outlining my approach to planning as it relates to patient selection and procedure selection (i.e., the type of TRAM flap selected), which is determined by aesthetic requirements and specific patient comorbidities (Table 7-2).

TABLE 7-2 TRAM Flap Procedure Selection | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Appropriate patient selection2,3 is a critical component of limiting complications following TRAM flap breast reconstruction. There are a number of factors that have been shown to increase the incidence of complications following TRAM flap reconstruction. Most notably these are cigarette smoking, obesity, previous abdominal incisions, and antecedent radiation therapy.

TRAM FLAP PROCEDURE SELECTION

From an aesthetic standpoint, tissue requirement (i.e., the amount of skin and adipose volume needed to achieve the desired breast reconstruction) is important to consider in each patient. Simply put, this is the amount of skin and subcutaneous adipose tissue that must be transferred from the lower abdomen to produce symmetry with the opposite breast.

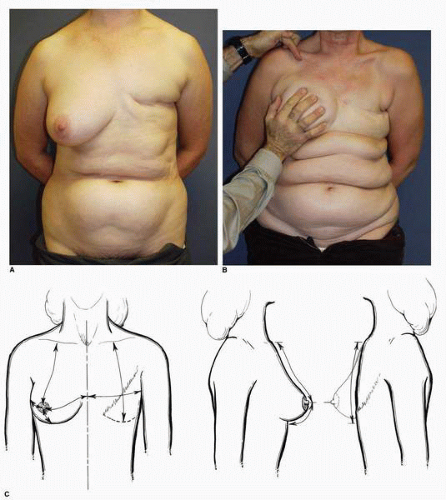

Accurately estimating the volume of the breast to be matched with the TRAM flap reconstruction is a critical first step. For me this is both a visual and tactile analysis. I carefully study the breast from the standpoint of its projection and distribution over the anterior chest wall (Fig. 7-1A). Normally the breast extends from the second to the sixth intercostal spaces and from the parasternal area to the anterior axillary line. Some breasts extend more superiorly and/or more laterally than others. I obtain a true estimate of the tissue needed for the volume restoration by grasping or gently cupping the patient’s breast with my hand. This gives me an appreciation of the superior extent of the breast tissue and the thickness of the tissue in this superior area (Fig. 7-1B).

Measurement of the skin deficit is a more straightforward task in that it can be done using a tape measure placed over the existing breast, first in the vertical midbreast meridian (measured from the midclavicular point down through the nipple to the IM fold) (Fig. 7-1C) and then horizontally across the most anteriorly projecting part of the breast. In the case of a delayed breast reconstruction, the surgeon can gain an accurate estimate of how much skin needs to be replaced by subtracting the smaller numbers on the side of the mastectomy from the larger skin dimensions on the contralateral breast.

I will then perform a similar maneuver in the lower abdominal region, again gently cupping the adipose tissue on either side of the lower abdominal midline (Fig. 7-1D) with my hand. This gives me the best idea of how much adipose tissue there is on one side of the lower abdomen and whether it will be enough to recreate a breast with adequate volume.

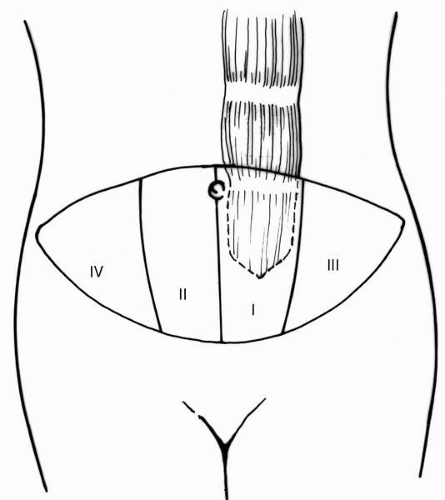

Clinical concepts about the circulatory dynamics of the superiorly based TRAM flap were initially proposed by Hartrampf3 after a thorough analysis. His observations gave rise to the idea of dividing the tissue of the lower abdomen into four zones (Fig. 7-2) based on the proximity of the adipose and skin tissue components to the nutrient muscle pedicle. He observed decreasing predictability in survival of tissue as one progressed laterally from zone I, the tissue overlying the muscle, to the random pattern circulation in zone III on the ipsilateral side, and then to the transmidline tissue in zone II and further laterally across the midline to zone IV, which is the tissue across the midline most distant from the musculocutaneous perforators. The clinical observations of Hartrampf3,4 and Bostwick5 have corroborated the anatomic studies of Taylor.6,7

This leads to a very important aspect of successful TRAM flap breast reconstruction, namely procedure selection. For me this is the process of determining which type of TRAM flap technique should be used to carry the tissue needed for the reconstruction that will best simulate the opposite breast. Different techniques provide different degrees of vascular perfusion to the adipose tissue zones2,3,8 in the flap. Therefore the procedure is selected based on predicted adequacy of the blood supply in an effort to minimize the risk of fat necrosis and other ischemia-related complications.

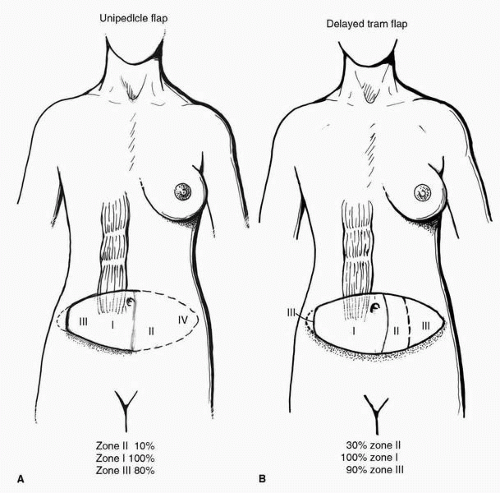

The TRAM flap can be designed as a unipedicle superiorly based flap1, 2 and 3 (Fig. 7-2) in those clinical cases where it is determined that the tissue on one side of the lower abdominal midline (zones I and III in Fig. 7-3A) will provide sufficient volume for the reconstruction (or a total of two zones or 50% of the total tissue in the lower abdomen). If more tissue than this is required, the surgeon must incorporate a maneuver to provide additional vascularity to the flap, such as performing a preliminary surgical delay9, 10 and 11 of the TRAM flap procedure (Fig. 7-3B), transferring it as a free microvascular12,13 flap (Fig. 7-3C), or using two muscles in the form of a bipedicle TRAM14,15 flap (Fig. 7-3D). These alternatives have been shown to increase the amount of lower abdominal skin and adipose tissue that can be reliably transferred while limiting the complications of fat necrosis and partial flap loss. My experience with the amount of lower abdominal adipose tissue and skin that can be reliably transferred with a minimum of fat necrosis is depicted in Figure 7-3A-D.

As stated earlier, both patient selection and procedure selection are important considerations in TRAM flap breast reconstruction.2

PATIENT SELECTION IN TRAM FLAP BREAST RECONSTRUCTION

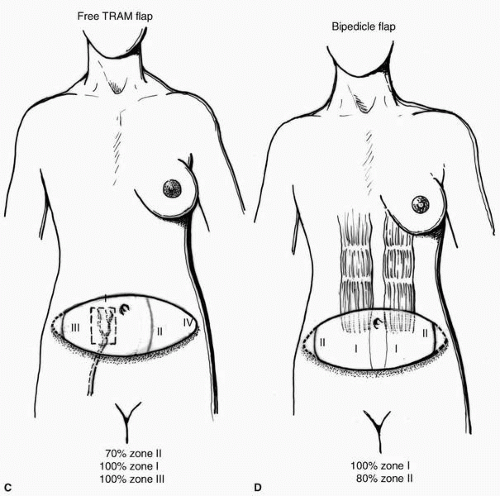

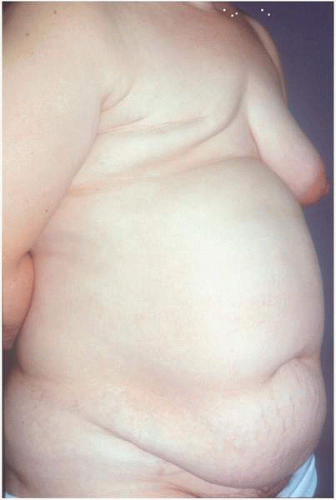

Patient selection has been stressed by Dr. Hartrampf,4 who not only is credited as being the originator of the procedure but also should be saluted for carefully studying his patients postoperatively and identifying the risk factors that put a patient at increased risk for complications (Table 7-2). This assessment involves taking a careful history and performing a physical examination. According to Hartrampf, factors that have been shown to increase the risk of complications include cigarette smoking, significant obesity (Fig. 7-4), underlying systemic diseases (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, and collagen vascular disorders), abdominal wall scars form previous surgical procedures, and prior radiation therapy. Watterson et al.5 corroborated Hartrampf’s initial observations in their review of 556 TRAM flaps, citing smoking, previous abdominal scars, and radiation therapy as the key risk factors that are especially predictive of an increased postoperative complication rate.

I believe that patients who smoke must stop completely for at least 6 weeks2,16,17 before surgery if a pedicled TRAM flap is to be considered. Otherwise, the incidence of vascular compromise in the tissues of the flap and the native skin of the breast region and abdominal wall skin increase dramatically.17 I carefully explain to each patient who smokes that it has been clearly documented that smoking increases the complication rate from surgical procedures everywhere in the body and stress that the patient can help herself immeasurably by quitting smoking completely before surgery.16 If the patient cannot do this then another form of breast reconstruction should be considered, or if the TRAM flap is the only option a free

microvascular TRAM should be done because this procedure takes advantage of the dominant blood supply to this tissue and minimizes the amount of tissue undermining the upper abdomen.12,13 Procedure selection is discussed later in this chapter.

microvascular TRAM should be done because this procedure takes advantage of the dominant blood supply to this tissue and minimizes the amount of tissue undermining the upper abdomen.12,13 Procedure selection is discussed later in this chapter.

It is also critical to note the presence and location of previous incisions,18 especially a right subcostal incision, that may have been used in the performance of a cholecystectomy. Such incisions carry the risk of having transected the rectus abdominis muscle and the superior epigastric artery, thereby eliminating the blood supplied to the hemi-TRAM flap by this vessel. In addition, this incision may also compromise the healing of the lower abdominal skin flap, which is advanced to close the donor site. Other incisions in the abdomen may also negatively impact the circulation to the flap tissues.18 These include a lower abdominal midline incision or McBurney-type oblique incision, especially if either was complicated by wound dehiscence or delayed healing. In summary, the breast reconstructive surgeon should carefully analyze every abdominal wall with previous scars to determine whether free TRAM or bipedicle procedure modifications are needed to complete the TRAM flap reconstruction with an adequate margin of safety.

Also important to note before surgery is the location, thickness, amount, and distribution of abdominal wall adipose tissue, and in particular its relationship to the underlying muscle. Sufficient adipose tissue in the lower abdomen is an obvious requirement for TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Patients with a thin adipose layer and extensive musculoaponeurotic laxity resulting in significant abdominal protuberance are at increased risk for both breast and donor-site complications. Similarly, patients who are obese and who have the majority of their adipose tissue below the arcuate line often show decreased vascular supply to this fat tissue (Fig. 7-4) and

are suboptimal candidates for TRAM flap reconstruction4,19,20 because of the increased complication rate seen in this population.

are suboptimal candidates for TRAM flap reconstruction4,19,20 because of the increased complication rate seen in this population.

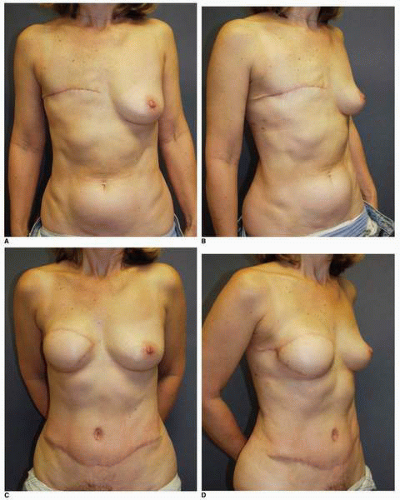

Interestingly, in my experience patients who are relatively thin or who have a mesomorphic-type build and a strong abdominal wall muscle layer are the best candidates for TRAM flap reconstruction (Fig. 7-5A-F) and achieve excellent aesthetic outcomes.

TRAM flap reconstruction is a procedure with tremendous aesthetic potential, but unfortunately the chance of complications occurring is great. As previously mentioned, a highly individualized reconstructive plan is essential if the aesthetic result is to be maximized and the incidence of complications is to be minimized.

AESTHETIC ANALYSIS OF THE CONTRALATERAL BREAST

From an aesthetic standpoint it is important to analyze the opposite breast for its size, base width and height dimensions, volume, volume distribution, projection, IM fold level and definition, and overall orientation on the chest wall. Breast shape or form can be visualized according to whether the breast mound exhibits a vertical, vertical oblique, or transverse form when viewed in the frontal plane.

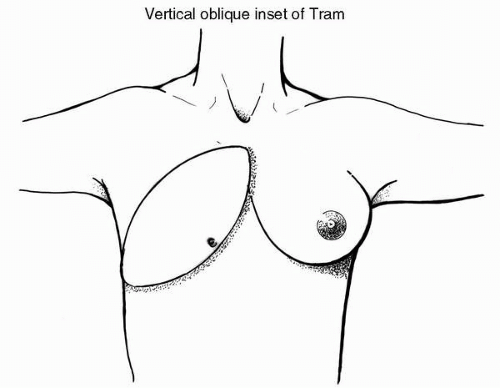

In my experience the most common breast shape encountered is the vertical-oblique form, which is marked by moderate inferomedial fullness that tapers more superiorly along the parasternal region as the woman moves. The breast tissue is located beyond the anterior axillary line inferiorly but also extends obliquely upward toward the tail of Spence (Fig. 7-6). Patients with this breast shape are most readily reconstructed by a TRAM flap that is positioned in a vertical-oblique manner.

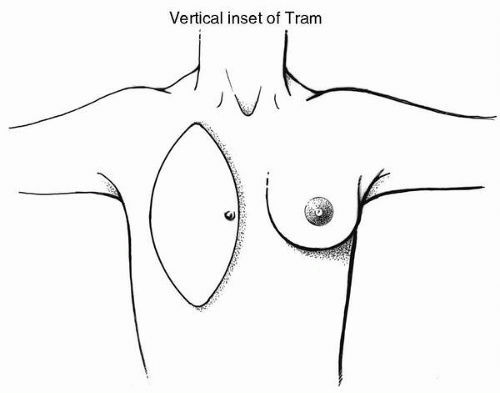

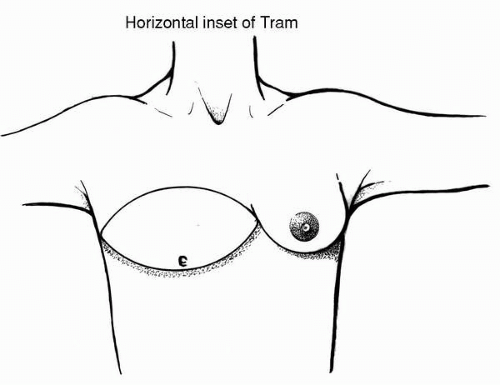

A vertical breast form (Fig. 7-7) demonstrates a narrow base width, less breast volume lateral to the anterior axillary line, moderate fullness medially in the parasternal area, and a superior extension of breast tissue to the second intercostal space. This type of breast is more common in tall, thin patients.8 Certain patients present a breast form with more lateral fullness, less vertical height, and significantly more anterior projection. These patients exhibit a horizontal or transverse orientation of their breast when viewed anteriorly (Fig. 7-8).

The aesthetic analysis is conducted to estimate tissue requirements and to determine if the contralateral breast can be matched by a TRAM flap or whether a modification of that breast will be necessary. If opposite breast modification is to be undertaken I prefer to perform this surgery at the time of the primary TRAM flap transfer so that both breasts can evolve together.

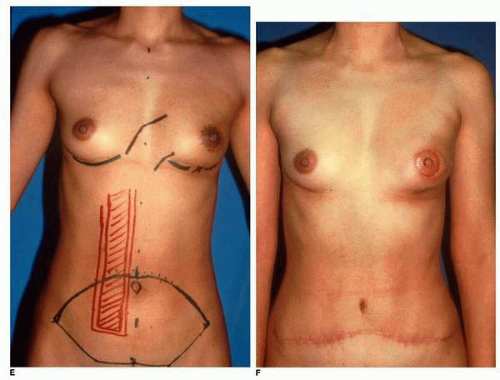

As previously mentioned, for me, a very critical aspect of TRAM flap breast reconstruction is the estimation of the skin and adipose tissue required to produce a new breast mound (see Fig. 7-1A-D). The surgeon must accurately gauge the tissue needed in this regard. The skin envelope is perhaps the critical component of every breast reconstruction.2,8 Recognizing this fact, the reconstructive surgeon must have a clear idea of how much skin must be replaced in every reconstruction. In the setting of delayed breast reconstruction, this is readily determined by measuring the amount of skin on the contralateral breast (Fig. 7-9A) in the superior-inferior and mediolateral dimensions and making corresponding measurements on the side of the mastectomy (Fig. 7-9B). This skin deficit must be replaced if the reconstructed breast is to show the best possible symmetry with the opposite breast (see Fig. 7-1C). Using the measurements taken the surgeon can produce a skin template (Fig. 7-9C) that can be drawn on the lower abdominal skin before surgery after the appropriate orientation for the TRAM flap inset has been selected (see Figs. 7-6, 7-7, and 7-8).

FIGURE 7-7. The second most common shape of the mature female breast is that of a vertical orientation. To duplicate such a shape, the TRAM flap should be inset in a vertical orientation. |

FIGURE 7-8. The least common breast shape is that of strong anterior projection with minimal upper pole fullness. Such a shape is duplicated by a transverse inset orientation of the TRAM flap. |

The other critical dimension to be considered in every breast reconstruction is the base width of the breast. This is visually appreciated from the frontal [anteroposterior (AP)] view. It is determined by measurements from the parasternal area to the midaxillary line and is discussed later in this chapter.

To achieve consistent success in TRAM flap reconstruction, the surgeon must accurately gauge the tissue needed to reconstruct the breast and determine whether there is sufficient tissue on one side of the lower abdominal midline to accomplish this important aesthetic goal (see Fig. 7-1D). This analysis is critical for selecting the type of TRAM flap procedure, i.e., whether a single pedicle, free TRAM, double pedicle, or delayed TRAM is best suited to achieve the aesthetic and reconstructive goals while minimizing the complications of fat necrosis or partial flap loss.

Procedure selection therefore depends on the tissue needed for the reconstruction, the tissue present in the lower abdomen, and an understanding of the circulatory dynamics of the tissues in the lower abdominal wall. Where possible, I prefer to use a superiorly based unipedicle TRAM flap (see Fig. 7-3A). However, if significantly more tissue than is present on more than one side of the lower abdominal midline (more than two zones of tissue)2,3 (see Fig. 7-2) is needed to achieve the reconstruction, additional blood supply must be provided to the transferred tissue. This brings into consideration the options of free flap transfer, the incorporation of both rectus muscles as carrier pedicles, and the recently developed option of preliminary surgical delay of the flap.

The circulation of the abdominal wall, and more specifically the TRAM flap tissue, has been well studied over the past 15 years. The most significant contributions to our knowledge in this area are derived from the many anatomic investigations and injection studies of Taylor.6,7 Boyd et al.6 initially investigated the circulation of the lower abdominal wall by means of dye injection studies. These studies illustrate that the blood supply is derived by three sources, namely the deep inferior epigastric artery (DIEA), the superior epigastric artery, and the intercostal arteries, with the deep inferior epigastric being the dominant pedicle.6

The determinants of circulation to the superiorly based TRAM flap (Fig. 7-10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree