21 Surgical Treatment of Vaginal Vault Prolapse and Enterocele

In recent years, the problem of pelvic organ prolapse has been given much more attention. Many women are living longer, and more interest exists in maintaining self-image of femininity and the capacity of sexual activity beyond menopause.

This chapter discusses the pathology and surgical correction of enterocele, uterovaginal prolapse, and posthysterectomy apical prolapse. Normal anatomy of the pelvic diaphragm is discussed in detail in Chapter 2. The evaluation of patients with pelvic organ prolapse, especially regarding their symptoms, physical examination, and diagnostic tests, is discussed in Chapters 5 and 6.

PATHOLOGY OF PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE

A useful approach to understanding the pathophysiology of prolapse was described by Bump and Norton (1998). They proposed considering risk factors for the development of prolapse as predisposing, inciting, promoting, or decompensating events. Predisposing factors are genetic, race, and gender; inciting factors are pregnancy and delivery, surgery such as hysterectomy for prolapse, myopathy, and neuropathy; promoting factors are obesity, smoking, pulmonary disease, constipation, and recreational or occupational activities; and decompensating factors are aging, menopause, debilitation, and medications. Depending on the combination of risk factors in an individual, prolapse may or may not develop over her lifetime. With further research on the human genome project, risk factors will continue to be identified. Eventually, we may be able to predict those at highest risk for developing prolapse. Modifiable risk factors can be altered to decrease the likelihood of subsequent prolapse. Obesity is one of the modifiable risk factors identified so far. Although increased parity is a risk factor for prolapse, nulliparity does not provide absolute protection against prolapse. Data from the Women’s Health Initiative (Hendrix et al., 2002) noted that almost one fifth of nulliparous women had some degree of prolapse. These data contradict those who enthusiastically promote cesarean delivery for all women to prevent prolapse.

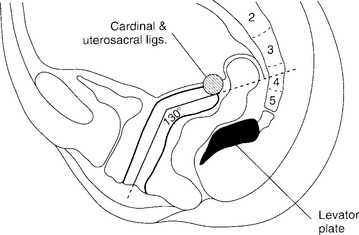

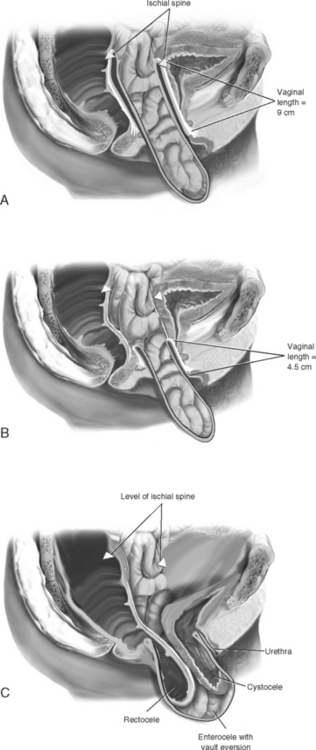

Normally, the vaginal axis in an erect woman is nearly horizontal in the upper half of the vagina, with the uterus and upper 3 or 4 cm of the vagina lying over the levator plate in the hollow of the sacrum (Fig. 21-1). Funt et al. (1978) found that the vagina is directed toward the S3 and S4 vertebras and extends approximately 3 cm past the ischial spines in most nulliparous women. Increases in intra-abdominal pressure compress the vagina anteriorly to posteriorly over the contracted levator muscles in the midline (levator plate). Diminished muscle tone may result in loss of stability of the levator plate, widening of the levator hiatus, and loss of an adequate base to support the upper vagina and uterus in the normal axis. Distortion of the normal vaginal axis during reconstructive pelvic surgery predisposes women to the development of pelvic organ prolapse at an anatomic site opposite to where the repair was performed. Examples of this are the development of posterior vaginal wall prolapse after colposuspension procedures for stress incontinence and the development of anterior vaginal wall prolapse after suspension of the vaginal apex to the sacrospinous ligament.

Connective tissue defects have been found in women with uterine prolapse and stress incontinence. In several studies, Mädakinen et al. (1986), 1987) identified abnormal histologic changes in the pelvic connective tissue in 70% of women with uterine descent, compared with 20% of normal controls. Decreased cellularity (fibroblasts) and an increase in collagen fibers were observed. Ulmsten et al. (1987) reported 40% less total collagen in the skin and round ligaments of women with stress incontinence when compared with that of continent women. These studies and others suggest that abnormal connective tissue may be associated with pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence.

PREVALENCE AND DEMOGRAPHICS

Because the prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse increases with age, the changing demographics of the world’s population will result in even more affected women. Based on projections from the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of American women age 65 and over will double in the next 25 years to more than 40 million women by 2030. One study by Luber et al. (2001) noted that the demand for health care services, related to pelvic floor disorders, will increase at twice the rate of the population itself.

Using data from a large U.S. Northwest health maintenance organization database, Olsen et al. (1997) reported the risks of pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence surgery by age 80 as 11.1%. Surgery for pelvic organ prolapse with continence surgery (22%) or without (41%) accounted for 63% of this risk, or a lifetime risk of 7%. Boyles et al. (2003) reported that over a nearly 24-year period reviewed, the rate of procedures to correct prolapse decreased slightly, but not significantly, and that the surgical indication for approximately 7% to 14% of hysterectomies is listed as pelvic organ prolapse. Data from the U.S. National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS) indicate that approximately 200,000 women undergo surgery for pelvic organ prolapse annually. A study by Brown et al. (2002), using data from the NHDS for surgical rates, indicated that approximately 22.7 per 10,000 women had some form of pelvic organ prolapse surgery in a year. As expected, surgical rates vary with age peaking in the sixth decade, with an average age of surgery of 55 years. Racial differences were also reported, with Caucasian women having a threefold greater rate of pelvic organ prolapse surgery than African American women. Pelvic organ prolapse is common worldwide. Samuelsson et al. (1999) reported a prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse of 30.8% among Swedish women ages 20 to 59, with 2% having prolapse to the introitus. In the United Kingdom two hospitalizations per 1000 person-years for pelvic organ prolapse occur by age 60 (Mant et al., 1997). Sajan and Fikree (1999) reported that 19.1% of women in Pakistan who were under age 30 reported feeling symptoms of prolapse.

ENTEROCELE

Definition and Types

Generally, enteroceles have been divided into four types: congenital, traction, pulsion, and iatrogenic. Congenital enterocele is rare. Factors that may predispose to the development of congenital enterocele include neurologic disorders, such as spina bifida and connective tissue disorders. Traction enterocele occurs secondary to uterovaginal descent, and pulsion enterocele results from prolonged increases in intra-abdominal pressure. The two latter types of enterocele may coexist with apical vaginal prolapse, cystocele, or rectocele. Iatrogenic enterocele occurs after surgical procedures that elevate the normally horizontal vaginal axis toward a vertical direction; examples include colposuspension and needle urethropexy operations for stress incontinence, or hysterectomy, with or without repair, when the vaginal cuff and cul-de-sac are not managed effectively.

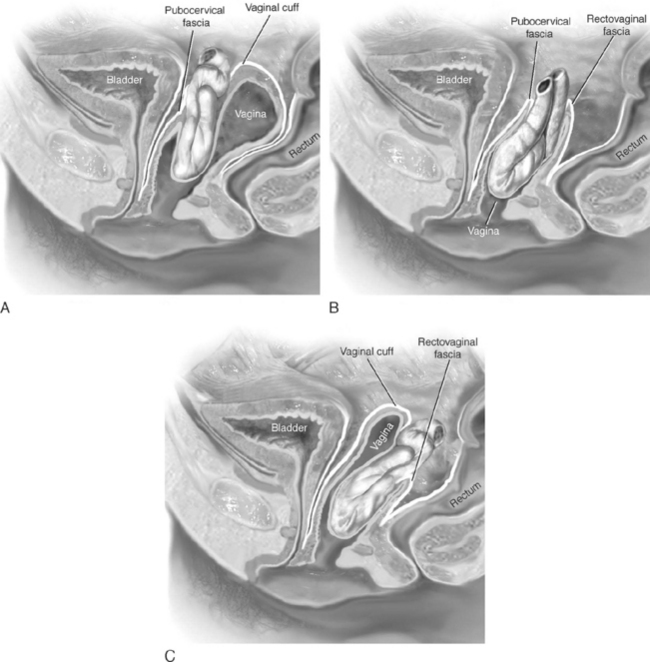

Clinically, enteroceles are best classified based on their anatomic location. Apical enteroceles herniate through the apex of the vagina, posterior enteroceles herniate posteriorly to the vaginal apex, and anterior enteroceles herniate anteriorly to the vaginal apex (Fig. 21-2).

Diagnosis

Enteroceles may commonly occur in association with rectocele and/or cystocele. When these hernias coexist with rectoceles, the rectovaginal examination may demonstrate the rectocele as distinct from the bulging sac that arises from a higher point in the vagina. Visual inspection of the posterior vaginal wall may reveal a transverse furrow between the two hernias. However, in many posthysterectomy prolapse patients, it is difficult to preoperatively determine whether an enterocele sac coexists with a large rectocele or cystocele. For this reason, in cases of advanced anterior or posterior vaginal wall prolapse, the surgeon should attempt to determine whether a portion of the prolapse is secondary to an enterocele. This should include routine dissection of the vagina from its underlying structures all the way to the apex of the vagina. The enterocele sac can usually be visually or digitally identified as a sac of peritoneum separate and distinct from the wall of the bladder or rectum. At times, a finger in the rectum or retrograde filling of the bladder may assist the surgeon in safely isolating and entering an enterocele sac.

Surgical Repair Techniques

VAGINAL ENTEROCELE REPAIR

MCCALL CULDOPLASTY

McCall (1957) described the technique of surgical correction of enterocele and a deep cul-de-sac at the time of vaginal hysterectomy. The advantage of the McCall culdoplasty is that it not only closes the redundant cul-de-sac and associated enterocele but also provides apical support and lengthening of the vagina. Many authors advocate using this procedure as part of every vaginal hysterectomy, even in the absence of enterocele, to minimize future hernia formation and vaginal vault prolapse.

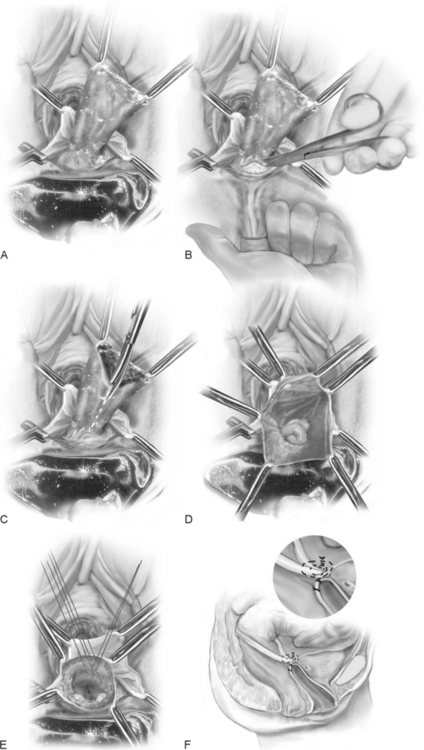

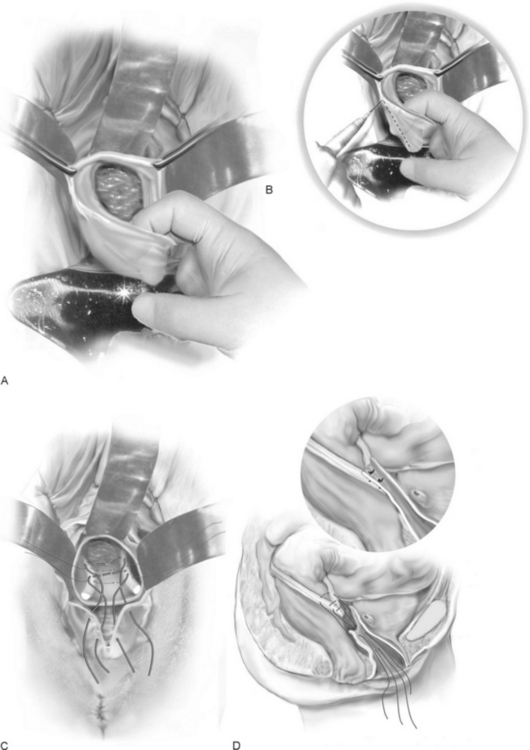

The technique is as follows (Fig. 21-4):

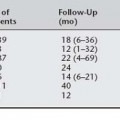

The complications as reported by Given (1985) after McCall culdoplasty are shown in Table 21-1. He reported ureteral injury in 1 of 48 McCall culdoplasty procedures. Stanhope et al. (1991) also found that culdoplasty sutures were implicated in ureteral obstruction after vaginal surgery. To ensure ureteral patency, cystoscopy should be routinely considered after the McCall culdoplasty.

Table 21-1 Complications After McCall Culdoplasty*

| Complication | Percent of Patients (N = 48) |

|---|---|

| Removal of silk suture | 10 |

| Postoperative cuff infection | 4 |

| High rectocele | 4 |

| Partial prolapse of vaginal vault | 4 |

| Shortened vagina | 4 |

| Introital stenosis | 2 |

| Pulmonary emboli | 2 |

| Nerve palsy | 2 |

| Ureteral obstruction | 2 |

* Follow-up was 2 to 22 (average 7) years.

From Given FT. “Posterior culdeplasty”: revisited. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1985;153:135, with permission.

When there is excessive redundancy of the posterior vaginal wall and peritoneum, a modification of the McCall culdoplasty, in which a wedge of posterior vaginal wall and peritoneum is excised, can be considered (Fig. 21-5).

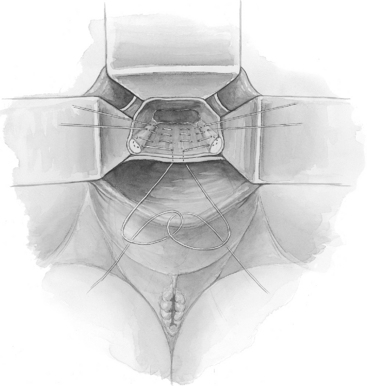

ABDOMINAL ENTEROCELE REPAIRS

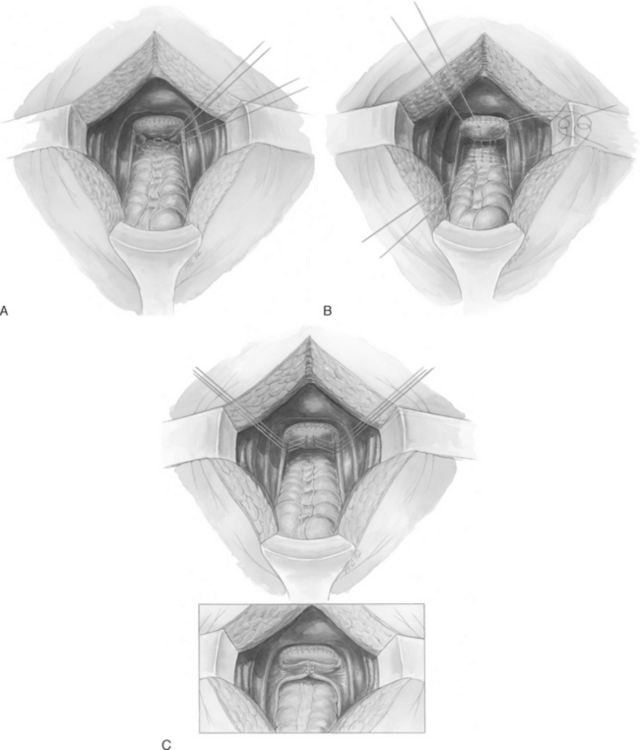

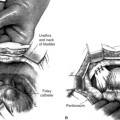

Three techniques of abdominal enterocele repair have been described: Moschcowitz and Halban procedures and the uterosacral ligament plication. The Moschcowitz procedure is performed by placing concentric purse-string sutures around the cul-de-sac to include the posterior vaginal wall, the right pelvic side wall, the serosa of the sigmoid, and the left pelvic side wall (Fig. 21-6, A). The initial suture is placed at the base of the cul-de-sac. Usually, three or four sutures completely obliterate the cul-de-sac. The purse-string sutures are tied so that no small defects remain that could entrap small bowel or lead to enterocele recurrence. Care should be taken not to include the ureter in the purse-string sutures or to allow the ureter to be kinked medially when tying the sutures.

Halban described a technique to obliterate the cul-de-sac using sutures placed sagittally between the uterosacral ligaments. Four or five sutures are placed sequentially in a longitudinal fashion through the serosa of the sigmoid, into the deep peritoneum of the cul-de-sac, and up the posterior vaginal wall (Fig. 21-6, B). The sutures are tied, obliterating the cul-de-sac.

Transverse plication of the uterosacral ligaments can be used to obliterate the cul-de-sac (Fig. 21-6, C). Three to five sutures are placed into the medial portion of one uterosacral ligament, into the back wall of the vagina, and into the medial portion of the opposite uterosacral ligament. The lowest suture incorporates the anterior rectal serosa to bring the rectum adjacent to the uterosacral ligaments and vagina. Care must be taken to avoid entrapment or kinking of the ureter. Relaxing incisions can be made in the peritoneum lateral to the uterosacral ligaments to release the ureters, if necessary.

VAGINAL PROCEDURES THAT SUSPEND THE APEX

When mild forms of isolated uterovaginal prolapse (descent of the cervix not beyond the midportion of the vagina) are present, vaginal hysterectomy and culdoplasty, with anterior and posterior colporrhaphy, are usually sufficient to relieve the patient’s symptoms and restore normal vaginal function. However, more severe apical prolapse requires separate operations to re-suspend the apex. In Figure 21-7, A an isolated apical enterocele is shown with a wells-supported anterior and posterior vaginal walls. In such a case, no formal vaginal vault suspension is necessary because simple excision and closure of the enterocele sac will result in a well-supported vagina of adequate length. As more of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls become everted, the more complex the repair becomes (Fig. 21-7, B, C).

Sacrospinous Ligament Suspension

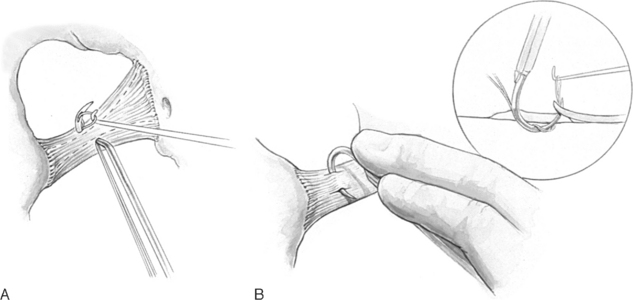

SURGICAL ANATOMY

To perform this procedure correctly and safely, the surgeon must be familiar with pararectal anatomy as well as the anatomy of the sacrospinous ligament and its surrounding structures (Fig. 21-8).

The sacrospinous ligaments extend from the ischial spines on each side to the lower portion of the sacrum and coccyx. Nichols and Randall (1989) described the sacrospinous ligament as a cordlike structure lying within the substance of the coccygeus muscle. However, the fibromuscular coccygeus muscle and sacrospinous ligament are basically the same structure and thus called the coccygeus-sacrospinous ligament (C-SSL). The coccygeus muscle has a large fibrous component that is present throughout the body of the muscle and on the anterior surface, where it appears as white ridges. The C-SSL can be identified by palpating the ischial spine and tracing posteriorly and medially the flat triangular thickening to the sacrum The fibromuscular coccygeus is attached directly to the underlying sacrotuberous ligament.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

The technique of unilateral sacrospinous fixation is as follows: