Chapter 22 Surgical Management of Migraine Headaches

Summary

Introduction

Migraine headaches (MH) are a significant cause of morbidity, affecting over 28 million Americans, with a lifetime prevalence estimated to be between 11% and 32% across several countries.1–6 MH are ranked as #19 among all diseases worldwide causing disability.7–9 The cost of medical treatment of MH in the USA has been estimated at 14 billion US dollars.10 There is an additional burden of 13 billion US dollars for loss of work. There are two subtypes of migraine: without aura, and with aura. Auras develop over 5-20 minutes, but last for less than 60 minutes, and are followed by a migraine. One out of three patients with MH experience aura.

MH are usually frontotemporal, typically unilateral, and are characterized by recurrent attacks of pulsating, intense pain associated with nausea and photophobia. The diagnostic criteria of migraines are shown in Table 22.1. Traditional, nonsurgical treatment of migraines can be nonpharmacologic or pharmacologic. Nonpharmacologic treatment of migraines consists of avoidance of triggers, usually caffeine, alcohol, or tobacco. Pharmacologic treatment can be further subdivided into acute analgesic, acute abortive, and prophylactic treatment. Acute analgesic treatment consists of pain control, acetaminophen, non-ste-roidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), analgesics, benzodiazepines, opioids, and barbituates. First-line acute abortive treatment is triptans, although IV antiemetics and ergotamine can be used as well. Prophy-lactic treatment consists of beta blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, and valproic acid.11

Table 22.1 Migraine headache diagnostic criteria

(Adapted from International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. 2nd edn. Cephalalgia 2004; 24(Suppl 1):9-160).

Though tension headaches can be confused with migraine without aura, it is possible to distinguish them from migraine, because tension headaches are not associated with nausea and are not affected by activity. Another group of headaches to be separated from MH are cluster headaches. Cluster headaches are marked by severe pain and affect the orbital, supraorbital, or temporal regions exclusively.12 They are 15-180 minutes in duration, and are associated with unilateral autonomic disturbances, such as conjunctival injection, lacrimation, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, forehead and facial sweating, miosis, ptosis, and eyelid edema. During an attack, the headaches occur once every other day up to eight times a day. In contrast to MH, patients with cluster headaches are typically restless and agitated.

Nonpharmacologic treatment of cluster headache consists of avoidance of ethanol, histamine, nitroglycerine, or tobacco. Abortive treatment consists of 100% oxygen, triptans, cafergot, and dihydroergotamine. Prophylactic treatment consists of verapamil, lithium, methysergide, ergotamine tartrate, and prednisone taper.13

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology of MH

Though migraine pathophysiology has not been completely elucidated, there are several plausible and experimentally substantiated theories. Importantly, these explanations incorporate both central and peripheral nervous-system activity, and these factors interact and lead to MH. There are four mechanisms in the pathogenesis of MH.15 First, patients with MH have some experimental evidence of interictal cortical derangements, specifically hyperexcitability of cortical neurons. Second, periaqueductal gray matter (PAG), which is an antinociceptive modulator, becomes progressively dysfunctional in MH. Burstein14 provided evidence that the sensitization of nociceptors causes an increase in neuronal discharges, which causes an increase in sensitivity to all stimuli. In other words, the central nervous system is ramped up, compared to normal, in response to both normal and painful stimuli. Third, auras are caused by cortical spreading depression, and the cortical spreading depression itself might cause irritation of the trigeminal nerve nucleus caudus.15 Finally, trigeminal nerve irritation causes release of substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide, and neurokinin A in the cell bodies of the trigeminal nerve.15–17 The substances then travel along the nerve and produce a localized meningitis, and dilation of large vessels and dura mater innervated by the trigeminal nerve.1,2,15,18,19 Although this dilation is thought to cause MH, in our view it is the consequence of inflammation.

What causes the initial trigeminal nerve irritation is not exactly known. The anatomic relationship between trigeminal nerve branches and head and neck musculature provides the basis of the trigger site hypothesis of trigeminal nerve irritation in our opinion. Triggers sites are where nerves are irritated either by traversing the muscle or due to contact with it. This concept is borne out by anatomic studies. The trunk of the supratrochlear nerve, and branches of the supraorbital, which are both branches of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, pierce the corrugator and depressor supercilii. The fact that many patients with MH have evidence of corrugator hypertrophy provides support for this hypothesis, which is further reinforced by the beneficial effects attained from injection with botulinum toxin A. Branches of the ZMTBTN pierce the temporalis muscle. The greater occipital nerve pierces the semispinalis capitus muscle.20,21 In some ways, this is analogous to piriformis syndrome, in which contraction of the piriformis muscle results in sciatic nerve irritation.22,23

Like MH, the pathophysiology of cluster headaches is not well understood. What is known is that pain in cluster headaches is mediated by the first division of the trigeminal nerve, while autonomic activation is mediated by cranial parasympathetic outflow from the facial nerve. There is no brainstem activation in cluster headaches, which distinguishes it pathophysiologically from MH.24

Surgical Treatment

Rationale for surgical treatment

In 1931, Walter Dandy removed the inferior cervical and first thoracic sympathetic ganglions in two patients, hypothesizing that migraine pain had a clinical profile consistent with nerve involvement.25 In 1946, Gardner reported on the resection of the greater superficial petrosal nerve in 26 patients. Though he reported some success in migraine patients, he noted complications including nasal dryness, decreased tear production, and corneal ulcerations.26 Slightly more than two decades later, Murillo described temporal neurovascular bundle resection in 34 patients for treatment of migraine headaches.27 Shortly after, Murphy reported greater occipital neurectomy for occipital migraine.28 Murillo and Murphy both had shortcomings in the length of follow-up of their studies, and there was a sequela of numbness resulting from these procedures. These radical surgeries with morbid sequelae led to unacceptable surgical outcomes, but the idea that surgery has potential in the treatment of headaches has persisted.

The understanding that the glabellar muscle group (GMG, including the corrugator, depressor supercilii, and procerus) itself may contribute to the pathophysiology, means that resection of these muscles makes intuitive sense. Not only do these patients benefit functionally from the surgery, they also observe some aesthetic improvement. Furthermore, the involvement of the ZMTBTN, which is sometimes resected in facial rejuvenation procedures,2 makes transection of that nerve justifiable for the treatment of headaches, since temporalis muscle resection may result in a depression and may also be of some, although minor, functional consequence.

Preoperative History and Considerations

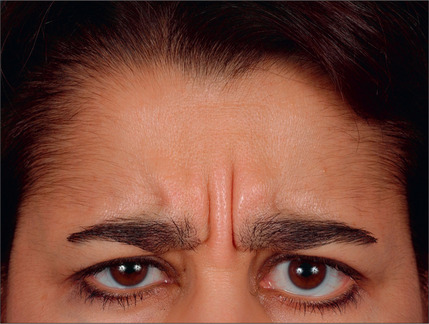

With the type of headache in mind, the ideal candidate for surgery must be identified. Studies have traditionally evaluated patients by the following criteria: proper diagnosis of headache (by headache questionnaire and evaluation by a physician trained in evaluating the headache patient), corrugator supercilii hypertrophy (Fig. 22.1), absence of medical or neurological conditions likely to cause headache, and the absence of unacceptable surgical risk. Pregnant and nursing women are also typically excluded from surgical consideration.

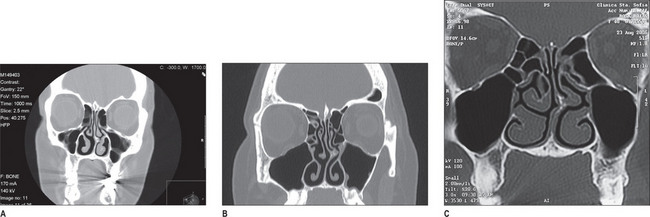

The constellation of symptoms leads the examiner to suspect the potential trigger sites,1–4 which is further validated by a nasal exam. The nasal exam includes direct and indirect endoscopic examination – which must be performed to detect septal deviation, turbinate hypertrophy, and concha bullosa – and findings are confirmed using a CT scan (Fig. 22.2).