19 Surgical Correction of Anterior Vaginal Wall Prolapse

ANATOMY AND PATHOLOGY

Anterior vaginal prolapse (cystocele) is defined as pathologic descent of the anterior vaginal wall and overlying bladder base. According to the International Continence Society (ICS) standardized terminology for prolapse grading, the term anterior vaginal prolapse is preferred over cystocele. The reason is because information obtained at the physical examination does not allow the exact identification of structures behind the anterior vaginal wall, although, in fact, it is usually the bladder. The ICS grading system for prolapse is discussed fully in Chapter 5.

The cause of anterior vaginal prolapse is not completely understood, but it is probably multifactorial, with different factors implicated in prolapse in individual patients. Normal support for the vagina and adjacent pelvic organs is provided by the interaction of the pelvic muscles and connective tissue, as discussed in Chapter 2. The upper vagina rests on the levator plate and is stabilized by superior and lateral connective tissue attachments; the midvagina is attached to the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis (white line) on each side. Pathologic loss of that support may occur with damage to the pelvic muscles, connective tissue attachments, or both.

Nichols and Randall (1996) described two types of anterior vaginal prolapse: distention and displacement. Distention was thought to result from overstretching and attenuation of the anterior vaginal wall, caused by overdistention of the vagina associated with vaginal delivery or atrophic changes associated with aging and menopause. The distinguishing physical feature of this type was described as diminished or absent rugal folds of the anterior vaginal epithelium caused by thinning or loss of midline vaginal fascia. The other type of anterior vaginal prolapse, displacement, was attributed to pathologic detachment or elongation of the anterolateral vaginal supports to the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis. It may occur unilaterally or bilaterally and often coexists with some degree of distention cystocele, with urethral hypermobility, or with apical prolapse. Rugal folds may or may not be preserved.

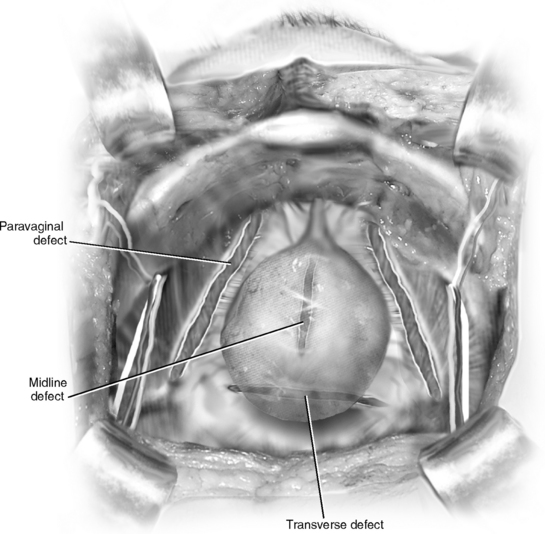

Another related theory ascribes most cases of anterior vaginal prolapse to disruption or detachment of the lateral connective tissue attachments at the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis or white line, resulting in a paravaginal defect and corresponding to the displacement type discussed earlier. This was first described by White in 1909 but disregarded until reported by Richardson in 1976. Richardson also described transverse defects, midline defects, and defects involving isolated loss of integrity of pubourethral ligaments. Transverse defects were said to occur when the “pubocervical” fascia separated from its insertion around the cervix, whereas midline defects represented an anteroposterior separation of the fascia between the bladder and vagina. A contemporary conceptual representation of vaginal and paravaginal defects is shown in Figure 19-1.

Few systematic or comprehensive descriptions of anterior vaginal prolapse have emerged based on physical findings and correlated with findings at surgery to provide objective evidence for any of these theories of pathologic anatomy. In a study of 71 women with anterior vaginal wall prolapse and stress incontinence who underwent retropubic operations, DeLancey (2002) described paravaginal defects in 87% on the left and 89% on the right. The arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis were usually attached to the pubic bone but detached from the ischial spine for a variable distance. The pubococcygeal muscle was visibly abnormal with localized or generalized atrophy in over half of the women.

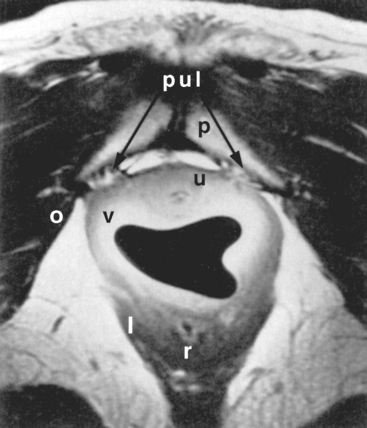

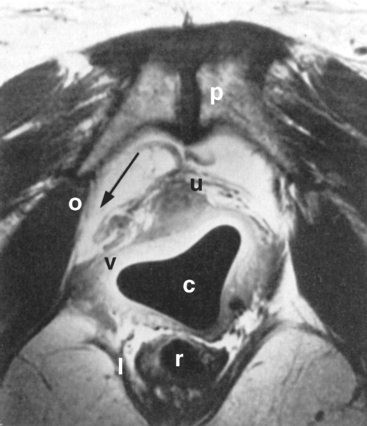

The pelvic organs, pelvic muscles, and connective tissues can be identified easily with MRI. Various measurements can be made that may be associated with anterior vaginal prolapse or urinary incontinence, such as the urethrovesical angle, descent of the bladder base, the quality of the levator muscles, and the relationship between the vagina and its lateral connective tissue attachments. Aronson et al. (1995) used an endoluminal surface coil placed in the vagina to image pelvic anatomy with MRI, and compared four continent nulliparous women with four incontinent women with anterior vaginal prolapse. Lateral vaginal attachments were identified in all continent women. In Figure 19-2, the posterior pubourethral ligaments (bilateral attachment of arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis to posterior aspect of the pubic symphysis) are seen clearly. In the two subjects with clinically apparent paravaginal defects, lateral detachments were evident (Fig. 19-3). Although this study involved only a small number of subjects, it provides the basis for further work in describing the anatomic abnormalities that accompany anterior vaginal prolapse and other abnormalities of pelvic support. This, ultimately, may guide the choice of surgical repair.

EVALUATION

History

When evaluating women with pelvic organ prolapse or urinary or fecal incontinence, attention should be paid to all aspects of pelvic organ support. The reconstructive surgeon must determine the specific sites of damage for each patient, with the ultimate goal of restoring both anatomy and function.

Physical Examination

The physical examination should be conducted with the patient in the lithotomy position, as for a routine pelvic examination. The examination is first performed with the patient supine. If physical findings do not correspond to symptoms, or if the maximum extent of the prolapse cannot be confirmed, the woman is reexamined in the standing position. The grading systems for prolapse and measurement of urethral hypermobility are described in Chapters 5 and 6.

It may be possible to differentiate lateral defects, identified as detachment or effacement of the lateral vaginal sulci, from central defects, seen as midline protrusion but with preservation of the lateral sulci, by using a curved forceps placed in the anterolateral vaginal sulci directed toward the ischial spine. Bulging of the anterior vaginal wall in the midline between the forceps blades implies a midline defect; blunting or descent of the vaginal fornices on either side with straining suggests lateral paravaginal defects. Studies have shown that the physical examination technique to detect paravaginal defects is not particularly reliable or accurate. In a study by Barber et al. (1999) of 117 women with prolapse, the sensitivity of clinical examination to detect paravaginal defects was good (92%), yet the specificity was poor (52%) and, despite an unexpected high prevalence of paravaginal defects, the positive predictive value was poor (61%). Less than two thirds of women believed to have a paravaginal defect on physical examination were confirmed to possess the same at surgery. Another study by Whiteside et al. (2004) demonstrated poor reproducibility of clinical examination to detect anterior vaginal wall defects. Thus, the clinical value of determining the location of midline, apical, and lateral paravaginal defects remains unknown.

Diagnostic Tests

In women with severe prolapse, it is important to check urethral function after the prolapse is repositioned. As demonstrated by Bump et al. (1988), women with severe prolapse may be continent because of urethral kinking; when the prolapse is reduced, urethral dysfunction may be unmasked with occurrence of incontinence. A pessary, vaginal retractor, or vaginal packing can be used to reduce the prolapse before office bladder filling or electronic urodynamic testing. If urinary leaking occurs with coughing or Valsalva maneuvers after reduction of the prolapse, the urethral sphincter is probably incompetent, even if the patient is normally continent. This situation is reported to occur in 17% to 69% of women with stage III or IV prolapse. In this situation, the surgeon should choose an anti-incontinence procedure in conjunction with anterior vaginal prolapse repair. If sphincteric incompetence is not present even after reduction of the prolapse, an anti-incontinence procedure may not be indicated.