Fig. 20.1

Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (Copyright CCF. Reprinted by permission of Cleveland Clinic Foundation)

Fig. 20.2

J pouch with a stapled ileal pouch anal anastomosis (Copyright CCF. Reprinted by permission of Cleveland Clinic Foundation)

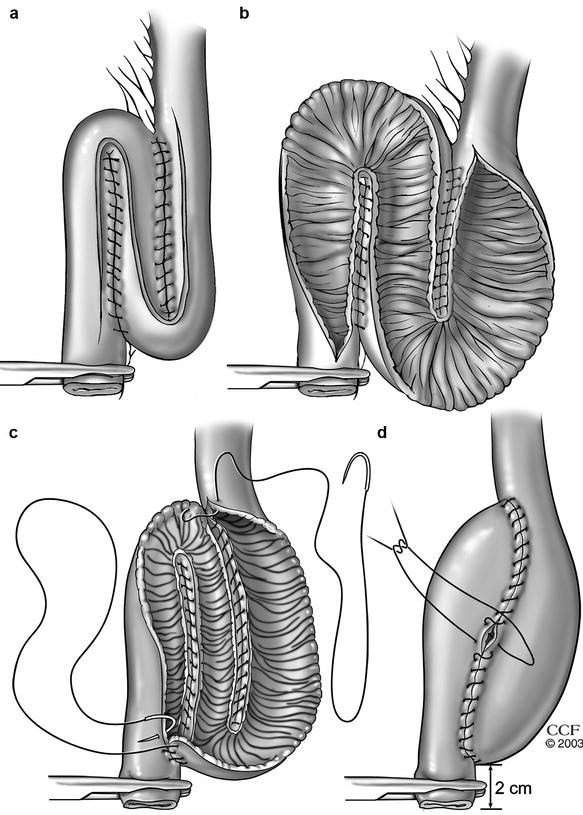

Fig. 20.3

Construction of an S pouch (a and b) An S-pouch is created with continuous seromuscular sutures by approximating the loops and an S-shaped enterotomy is then made. (c and d) The two posterior anastomotic lines are closed from inside the pouch with running sutures and then the anterior wall is closed with continuous seromuscular sutures (Copyright CCF. Reprinted by permission of Cleveland Clinic Foundation)

Fig. 20.4

Hand-sewn ileal pouch anal anastomosis (Copyright CCF. Reprinted by permission of Cleveland Clinic Foundation)

Septic complications are the most common short-term problems, whereas pouchitis and small-bowel obstruction are the most common long-term problems encountered [4 5]. Although the incidence of complications has decreased over time because of improved management strategies [5], these complications may still result in pouch failure. Pelvic sepsis and Crohn’s disease are proposed as principal independent predictors of pouch failure [6], and a specific ileal pouch failure model has been created to predict the overall risk of failure [7]. The cumulative probability of pouch failure has been reported as 2 % at 1 year, 5 % at 5 years, and 9 % at 10 years [5]. A failed pouch can be salvaged with reoperative surgery in an effort to avoid a permanent ileostomy with or without pouch excision (PE) [8–31]. The outcomes following these procedures are encouraging: pouch function and QOL similar to that of primary IPAA can be achieved in the majority of patients.

Reoperative Surgery for IPAA Failure

Reoperative operations for IPAA failure include perineal, abdominal, or combined approaches. Successful outcomes of abdominal approaches that are most commonly reported are shown in Table 20.1. Sepsis is the principal indication for revisional pouch surgery as is a dreaded complication of pouch vaginal fistula, although many reports have shown that this may be accompanied in well-selected cases by pouch salvage and acceptable long-term functional outcome and QOL.

Table 20.1

Reports of success of abdominal reoperative pouch surgery

Author [reference] | Year | Patients (n) | Success rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Liljeqvist and Lindquist [8] | 1985 | 7 | 86 |

Nicholls and Gilbert [10] | 1990 | 5 | 100 |

Fazio et al. [15] | 1998 | 35 | 86 |

Cohen et al. [14] | 1998 | 24 | 79 |

Fonkalsrud and Bustorff-Silva [16] | 1999 | 90 | 95 |

Dayton [17] | 2000 | 16 | 100 |

MacLean et al. [20] | 2002 | 57 | 74 |

Heuschen et al. [21] | 2002 | 39 | Not stated |

Shah et al. [22] | 2003 | 16 | 62 |

Dehni et al. [25] | 2005 | 45 | 93 |

Baixauli et al. [23] | 2004 | 100 | 75 |

Tekkis et al. [26] | 2006 | 112 | 79 |

Mathis et al. [30] | 2009 | 51 | 89 |

Shawki et al. [28] | 2009 | 23 | 69 |

Remzi et al. [27] | 2009 | 241 | 85 |

In a series of 114 patients requiring reoperation after an IPAA, Galandiuk and colleagues [9] used a range of procedures that included local anal techniques for septic complications, such as seton drainage for perianal abscesses, laparotomy with intra-abdominal abscess drainage, or formal pouch reconstruction. Restoration of pouch function was achieved in two thirds of patients, 70 % of whom ultimately had “excellent clinical and functional outcomes.” Twenty percent of the group ultimately required PE – most commonly because of ongoing pelvic sepsis. In another Canadian report by Johnson et al. [24], of 22 patients undergoing pouch revision for pouch-vaginal fistula, 50 % healed after reoperative surgery. The success rate of an abdominoperineal approach in such fistula repair seems to be higher than that after perineal repair. In this respect, Shah et al. [22] also reported outcomes after reoperative surgery for pouch vaginal fistula in 60 patients, 28 % of whom had ongoing pelvic sepsis. Procedures included local repairs such as an ileal advancement flap (n = 39) and abdominal reoperative/reanastomotic procedures. After a median of 49 months’ follow-up, the overall healing rate was 52 %, whereas in the 16 patients undergoing repeat IPAA, the success rate was 62 %. Twenty-four patients were ultimately redesignated with a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, the presence of which was associated with a lower rate of healing. Similarly, Zmora et al. [18] reported a high rate of PE after reoperative surgery in patients with a delayed diagnosis of Crohn’s disease.

In the series of 24 patients undergoing reoperative surgery reported by Cohen et al. [14], half were for pouch vaginal fistula. Although the study patients underwent a mean of 2.9 local salvage procedures per patient before reoperative surgery, more than 75 % of the reoperative cases ultimately had successful outcomes. As a result, Cohen et al. concluded that radical reconstructive surgery can be performed in patients after unsuccessful local procedures with acceptable results. In another study from the UK [12] that included 27 patients who underwent pouch salvage surgery, pelvic sepsis was the major reason for failure after the revision. It was suggested that salvage surgery is advisable provided that there is no concomitant uncontrolled pelvic sepsis. This conclusion was supported in a series of 112 patients undergoing abdominal reoperative surgery, as reported by Tekkis et al. [26], where 5-year success was associated with nonseptic indications rather than septic complications. In contrast, Fazio et al. [15] reported a 95 % success rate 6 months after repeat IPAA performed for septic complications. These findings were similar to those reported by Dehni and colleagues [25] in 64 patients undergoing reoperative surgery using either a transanal or an abdominoperineal approach; most (n = 47) underwent revision for septic problems and, despite this, 94 % of patients had a functioning pouch at their last follow-up. It is accepted that sepsis has a higher risk but it represents the main indication for operative pouch revision, and our latest report of 241 patients confirmed similar success rates between patients undergoing abdominal reoperative surgery for septic complications and those in whom revision was indicated for nonseptic complications.

Pouch survival overall is possible in three quarters of reoperated cases where the principal indication is postoperative sepsis [20], and a first-up abdominoperineal reconstructive approach is recommended in patients with pouch failure caused by an IPAA vaginal fistula. This, however, is dependent upon the subset of patients requiring revision; others have reported that more minor surgery resulted in relatively low pouch failure rates (6.1 %), with higher PE rates (10.8 %) after major surgical revision [21].

Reoperative surgery for pouch dysfunction due to mechanical obstruction or a retained rectal stump after IPAA also is associated with good outcomes. In a report of seven patients with pouch failure caused by malposition of an S pouch with a long, kinked efferent limb [8] (Fig. 20.5), patients presented with significant evacuatory difficulty. During abdominoperineal revisional surgery, the pouch and its efferent conduit were mobilized and the efferent limb was shortened. The pouch then was placed in close proximity to the anus and a formal repeat IPAA was fashioned. Operations were successful in six (86 %) patients. Similarly, Nicholls and Gilbert [10] identified 41 patients presenting with symptoms due to a long efferent ileal limb. Six of these cases required revisional surgery. Length of efferent ileal limb was 8 cm or more in all patients undergoing surgery. This limb was resected and a repeat anastomosis was performed. Of three patients who underwent a transanal approach, two failed, and these two patients as well as another three underwent abdominoperineal reoperative surgery. All six patients ultimately had improved continence and evacuation. In this respect, Herbst et al. [11] described 16 patients with mechanical obstruction after IPAA, reporting a long efferent limb, a long anorectal cuff, or both in 11 patients along with a persistent stricture at the IPAA anastomosis in five cases. In their report, the pouch was mobilized and disconnected from the anastomosis, with a repeat IPAA fashioned via an abdominal approach. Outlet obstruction significantly improved in 12 patients (75 %). In another study by Fonkalsrud and Bustorff-Silva [16], 164 patients with chronic dysfunction of an ileoanal pouch underwent a mixture of transanal resections, abdominoperineal reconstructions, or new pouch creation, with success rates of 98, 92 and 86 %, respectively.

Fig. 20.5

Obstruction of the efferent limb (Copyright CCF. Reprinted by permission of Cleveland Clinic Foundation)

Patients with afferent limb obstruction after an IPAA might also develop pouch dysfunction and require surgery (Fig. 20.6). Read et al. [13] reported six patients undergoing laparotomy for unresolved obstruction due to afferent limb obstruction. In the study patients, bypass of the obstructed segment from the distal ileum to the pouch proved effective, but the addition of a concurrent “pouchopexy” was recommended because of the risk of recurrent afferent limb angulation. In a study from our institution [31] 18 patients with afferent limb obstruction mainly presented with intermittent obstructive symptoms. Nine cases had empiric balloon dilatation of the afferent limb, whereas eight patients underwent revisional surgery. One patient did not undergo any intervention. We concluded that intervention is usually required for patients with afferent limb obstruction and, this is associated with an overall good outcome.

Fig. 20.6

Obstruction of the afferent limb (Copyright CCF. Reprinted by permission of Cleveland Clinic Foundation)

Patients with a retained rectal stump after stapled primary IPAA may develop persistent symptoms and often need revisional surgery. In this regard, Tulchinsky et al. [19] identified 22 patients undergoing abdominoperineal reoperative surgery due to a retained rectal stump after an IPAA. Fifteen patients (68 %) reported subjective improvement in pouch function and QOL after surgery, although five patients ultimately required PE and a permanent stoma after a median follow-up of 22.5 months.

Experience at the Cleveland Clinic

The most recent study with a large number of patients from our institution [27

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree