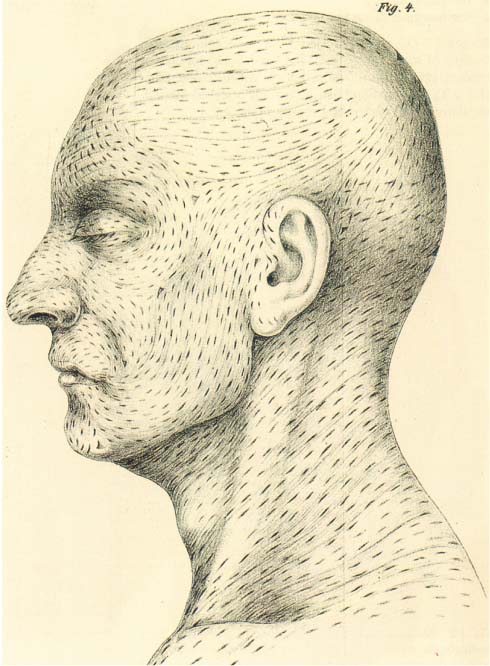

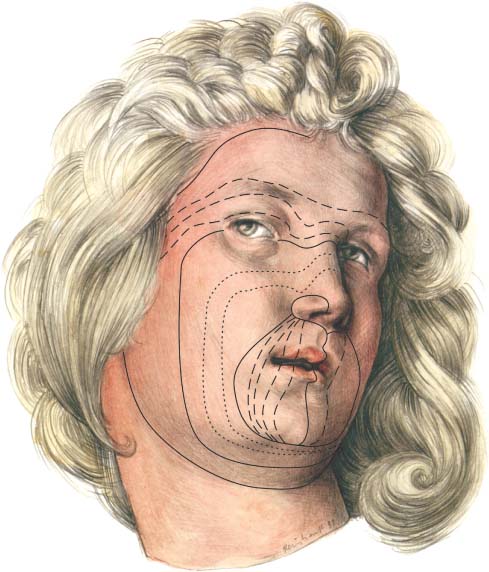

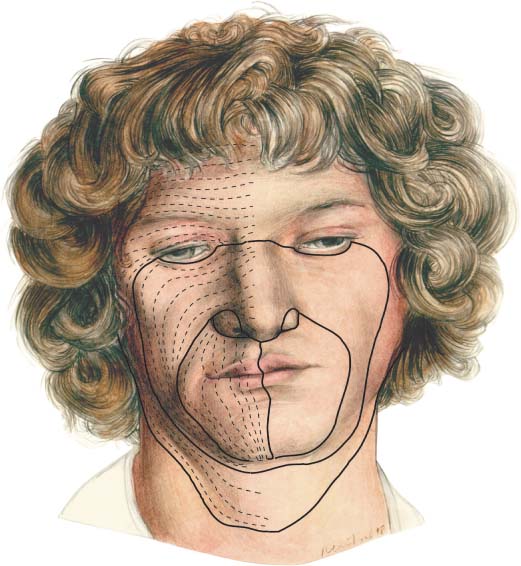

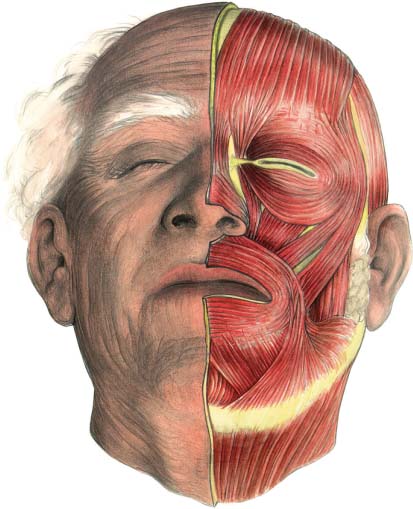

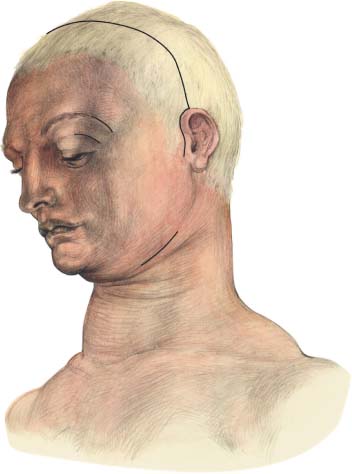

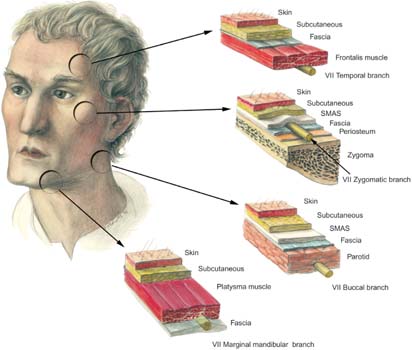

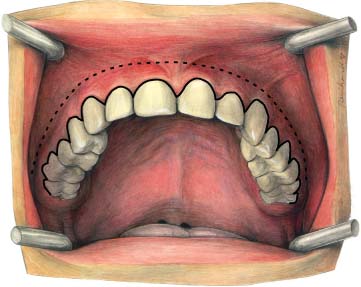

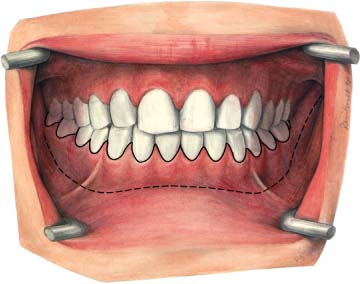

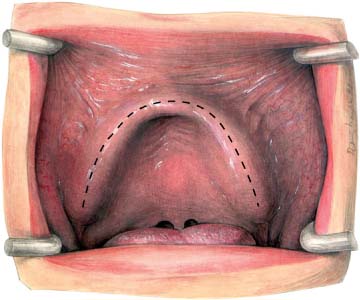

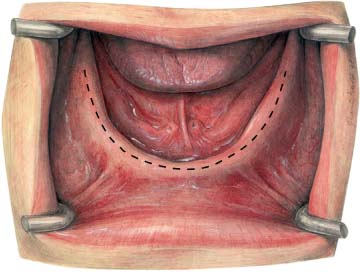

5 Surgical Approaches The surgeon is encouraged to regain the maximum function of injured skin or mucosa with the least possible deformity and scarring. The ultimate appearance and function of a scar can be predicted by the static and dynamic skin tensions on the surrounding skin (Thacker et al., 1975). Static tension lines exist within the skin and are oriented in specific but variable directions throughout the body. This was first recognized by Dupuytren in 1834. He examined a suicide victim who had sustained three self-inflicted puncture wounds made by an awl. He noted that the skin incisions either gaped apart or remained closed in a consistent way, depending on the direction of the incision and their site on the body. In 1861 Langer examined the skin of cadavers which were lying in a normal anatomical position. He inserted an awl to depths of 2 mm and 2.5 mm and so identified the direction of predominant tension. These static lines of maximal skin tension are now known as Langer lines (Fig. 5.1). Fig. 5.1 Langer lines were noted after puncturing the skin of cadavers with a sharp awl. (Langer, 1861, Fig. 4.) Fig. 5.2 Borges and Alexander “relaxed skin tension lines” indicate the directional pull that exists in relaxed skin. They can be determined by noting the “furrows and ridges” which are formed by pinching the skin (after Albrecht Dürer, Angel Head, 1506, Albertina, Vienna). Kocher was the first surgeon to recognize the surgical significance of Langer lines in 1892. He recommended that surgical incisions should be made in such a way as to follow the direction of Langer lines to obtain the best postoperative scars. This recommendation was reinforced by Kraissl (1951). However, Borges and Alexander (1962), while recognizing the importance of Langer lines, disputed their biological relevance, since they represented the lines of skin tension following rigor mortis. They observed that in the living body in a relaxed state, skin tension occurred in one specific direction (Fig. 5.2). They called this phenomenon “relaxed skin tension lines” (RSTL). On the face, Borges, Alexander, and Block (1965) distinguished four principal relaxed skin tension line directions: • the facial median line • the nasolabial line • the palpebral line • the marginal facial line Borges (1973) recommended that to obtain optimal healing of scars the surgical incision should follow the relaxed skin tension line direction within these areas (Fig. 5.3). Skin tension lines are usually oriented perpendicularly to the underlying muscles (Fig. 5.4). Today, it is generally recognized that the best aesthetic results in the face are obtained if the long axis of the scar lies in the direction of the maximal skin tension (Remmert et al., 1994). The more closely a wound follows the relaxed skin tension lines, the better the cosmetic result. An extraoral approach for mini- or microplate and screw application is rarely used. However, in some cases an extraoral approach (such as the classical submandibular, lower eyelid, upper lid blepharoplasty, brow and coronal approaches) is required (Fig. 5.5). When such an approach is used, the facial nerve is potentially at risk and therefore the surgeon must be aware of, and consider, the relevant anatomy (Fig. 5.6). The typical intraoral incision lines for exposure of either the maxilla or the mandible are made within the unattached mucosa 4–5 mm below the level of the attached gingiva (Figs. 5.7, 5.8). Fig. 5.3 The four principal relaxed skin tension lines. The facial median line, the nasolabial line, the palpebral line, and the marginal facial line (after Albrecht Dürer, Portrait of an 18 year old lad, 1503, Bibliothek der Akademie der Künste, Vienna). Fig. 5.4 Facial skin tension lines and facial muscle lines are usually oriented perpendicularly to muscles. Alternatively, to reduce scar tissue formation and minimize the risk of infection, the marginal rim incision can be used (see Figs. 5.7, 5.8). To expose the posterior part of the mandible, the incision line is placed directly over the ascending ramus of the mandible. For the edentulous patient the incision line for exposure of the maxilla and the mandible is usually on the crest of the alveolar ridge (Figs. 5.9, 5.10). Fig. 5.5 Preferred surgical approaches to the facial skeleton (after Albrecht Dürer, St. Apollonia, 1521, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin). Fig. 5.6 Cross-sectional anatomy of facial soft-tissue layers in relation to the facial nerve and its temporal and marginal mandibular branches, which are at risk during facial surgery (after Albrecht Dürer, Portrait of a young man, 1500, Bayrische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich). Fig. 5.7 Intraoral incision for exposure of the maxilla. Usually, this is made in the unattached mucosa 4–5 mm below the level of the attached gingiva (dashed line). Alternatively, the marginal rim incision (solid line) can be used. Fig. 5.8 Intraoral incision for exposure of the mandible. Details as in Fig. 5.7. Fig. 5.9 Intraoral incision for exposure of the edentulous maxilla is made on the crest of the alveolar ridge. Fig. 5.10 Intraoral incision for the exposure of the edentulous mandible is made on the crest of the alveolar ridge.

Biomechanical Principles

Extraoral Incision

Intraoral Incisions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree