Skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) is a very common cause of patient presentation to primary care and the emergency department. SSTIs comprise nearly 20% of patient visits to dermatology providers. The normal skin of a healthy individual is naturally resistant to infection. The normal skin flora actually protect us from invasion of other organisms which vary by anatomic location. Staphylococcus aureus, a gram-positive organism, is usually found on the surface of exposed skin, while Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a gram-negative bacteria, occurs on the moist areas of axilla, groin, and web spaces.

Several elements, however, can upset the host-bacteria relationship and transform the status quo into an infectious state. The risk of pathogenesis is influenced by the virulence of the organism, the portal of entry, and the ability of the host to defend and respond to the presence of the organism.

Bacterial infections, also known as pyoderma of the skin, can manifest either as a primary cutaneous process, such as impetigo, or as a manifestation of a systemic infection such as toxic shock syndrome (TSS). This chapter will focus on the recognition and treatment of common SSTIs including those infections that have systemic involvement.

The clinician’s ability to recognize and treat infections of the skin early in the course of the disease will insure that patients receive optimal antimicrobial therapy when indicated. Likewise, the ability to distinguish true infection from other inflammatory conditions will spare our patients the risk and expense of unnecessary medicines.

Treatment for bacterial infections often requires the use of antibiotics and other antimicrobial drugs. Proper use of this group of medicines will be discussed primarily as they pertain to dermatology. Alternative treatments will be suggested when possible to minimize the frequency of drug resistance.

ANTIBIOTIC SELECTION

Antibiotic selection is pivotal to the treatment of any bacterial infection, and the optimum choice is based on many factors. The individual pathogen and its susceptibility profile will largely determine the most appropriate antimicrobial. The mechanism of action (MOA) will determine whether the drug is bacteriostatic or bacteriocidal. In other words, you need to choose the right drug for the specific bug. In addition, drug interactions and adverse effects must be considered along with the patient’s immune status, age, pregnancy state, and genetic predisposition. A history of drug allergy is essential when deciding treatment; however, many patients confuse true allergy with gastrointestinal upset, especially if they were advised to discontinue the drug. The degree of a penicillin allergy, for example, may not prohibit the use of cephalosporins if needed, so a careful and probing history is sometimes required.

The increase in drug resistance in the United States is in part the result of improper prescribing without bacteriologic information to support its use. Drugs can sometimes be eliminated altogether if other interventions such as incision and drainage and supportive measures are instituted. It is important to remember the old rule when prescribing medication: “Right drug, right dose, right duration, right patient and right time” (

Dryden, Johnson, Ashiru-Oredope, & Sharland, 2011).These decisions demand that we as clinicians possess a thorough understanding of the available classes of drugs, their MOA, and effectiveness in various conditions as well as special circumstances in which they should not be used.

This section briefly reviews the common classes of antibiotics used effectively in dermatology for the treatment of SSTIs.

Topical Antibiotics

Drugs such as mupirocin (Bactroban), retapamulin (Altabax), neomycin, gentamycin, polymyxin, and bacitracin are often used in the treatment of superficial skin infections. The greatest drawback is their propensity for allergic contact dermatitis. Subsequently, most dermatologists advocate the use of white petrolatum only on surgical wounds and minor trauma. Topical antibiotics, however, have long been successful in the treatment of acne and rosacea (see

chapter 4).

Systemic Antibiotics

These agents are classified by their potential to eradicate or inhibit the growth of the bacteria. Although they can be very effective, there is significant potential for adverse effects and drug interactions. The MOA will determine whether the drug is bacteriostatic or bacteriocidal and will therefore influence the course of treatment.

Penicillins

Penicillins are β-lactam antibiotics and are bacteriocidal agents. Their MOA is to inhibit bacterial cell wall synthesis by binding or destroying enzymes needed for cell growth. Dicloxacillin is highly effective against β-lactamase resistant-penicillin. Oxacillin, cloxacillin, and floxacillin are all used effectively for pyoderma caused by Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus.

Cephalosporins

As with penicillins, cephalosporins inhibit the enzymes needed for cell wall formation and are bacteriocidal. They have been grouped by multiple generations based on their antimicrobial activity. The first generation (cephalexin, cefazolin, cephadroxil) is very effective against staphylococci and nonenterococcal streptococci. It is not usually effective against methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). The second generation (cefaclor, loracarbef, cephproxil, cefuroxime axetil) is less effective against gram-positive organisms and more effective against gram-negative organisms. The third generation (ceftriaxone, ceftizoxime, cefixime, cefoperazone) also has good gram-negative activity and especially good activity against P. aeruginosa.

Macrolides

While erythromycin was the first drug in this class, it has been outfavored by the newer macrolides because of its significant GI side effects and lack of activity against gram-negative organisms.

Clarithromycin, azithromycin, and dirithromycin are the newer macrolides. They are bacteriostatic and work by penetrating the cell walls of the bacteria. They then bind to the ribosome, inhibiting the RNA-dependent protein synthesis. Both clarithromycin and azithromycin have good activity against gram-positive

Staphylococcus and

Streptococcus and are also effective against atypical mycobacteria and toxoplasma gondii. They are used effectively in the treatment of pyodermas, abscesses, infected wounds, erysipelas, and ulcers.

β-Lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations such as amoxicillin/clavulanate and ampicillin/sulbactam have good activity against MRSA, some

Klebsiella species,

Haemophilus species

, E. coli, and

Proteus. They are very useful in polymicrobial infections such as animal or human bites (see

chapter 13).

Quinolones

The quinolones also have several generations of bacteriocidal agents. The second-generation drugs—ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin—are very effective against intracellular pathogens. They are the most effective drugs against gram-negative P. aeruginosa. The third generations—levofloxacin and moxifloxacin—have a very broad spectrum of action, including some atypical pathogens. Ciprofloxacin otic solution is useful in treating external otitis media. Diabetic foot ulcers, wounds, and interdigital toe-web infections are all improved with proper use of quinolones.

Tetracycline

The tetracycline family is widely used in dermatology more often for its anti-inflammatory rather than antimicrobial properties. They are bacteriostatic and have been more effective against grampositive than gram-negative organisms. Many group A streptococci are resistant to tetracycline and it is not available in the United States at this time. Minocycline and doxycycline are widely used for acne and related disorders because of its effect on propionibacteria. Doxycycline is excreted through the GI tract and is the only tetracycline acceptable for use in renal failure. While highly effective for use in acne, photosensitivity is common and may prohibit use in individuals who work outdoors or spend significant time exposed to the sun.

Miscellaneous Drugs

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

This combination antimicrobial is effective against S. aureus and S. pyogenes but is not widely used because of its propensity to cause hypersensitivity reactions. It has found favor of late, however, in the treatment of MRSA infections. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) is contraindicated in patients taking methotrexate (interferes with folic acid synthesis) and warfarin (potentiates drug and increased risk of bleeding). Newer antibiotic agents such as linezolid and daptomycin are bacteriocidal and are very useful for severe soft tissue infections, including MRSA infections.

Discussion of the most common superficial bacterial infections will be divided into those caused by gram-positive and gram-negative organisms.

GRAM-POSITIVE BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

The two bacteria that most commonly cause skin infections are S. aureus and group A β-hemolytic streptococcus (GAS). S. aureus is present on all skin surfaces and is considered a normal part of skin flora. Streptococci, however, are secondary invaders and attack skin that is already traumatized, causing infections such as cellulitis. Infections caused by both of these organisms can range from a superficial skin infection to sepsis with multiorgan involvement.

Impetigo

Perhaps the most familiar and widely known infection of the skin is impetigo. This is a highly contagious, superficial skin infection usually found in children. Adults can also acquire it from direct skin-to-skin contact. It can be seen in two forms: nonbullous and bullous type.

Clinical presentation

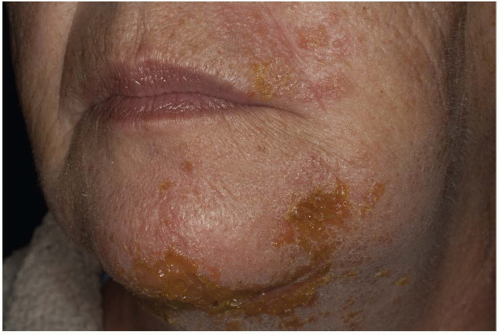

Nonbullous impetigo is the more common type and occurs primarily in children on the face (nose and mouth) and extremities. It usually begins as 2- to 4-mm erythematous macules that evolve into vesicles or pustules. Later, these lesions erode with the hallmark honey-colored crusts and surrounding erythema. These lesions tend to be asymptomatic, but itching and soreness may be mild. Systemic symptoms rarely occur (

Figure 9-1).

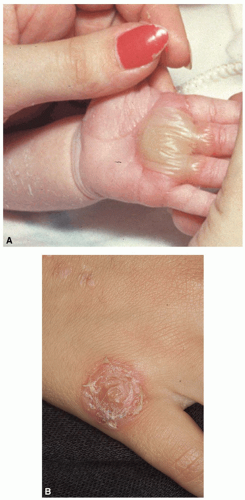

Bullous impetigo is less common and tends to occur in neonates and children. It begins as small vesicles that later develop into large bullae. These blisters are flaccid, and the contents may be clear or cloudy (

Figure 9-2A). The blisters break easily and develop a perimeter of scale which may measure up to 5 cm, but no crust or surrounding erythema is seen (

Figure 9-2B). A crust may form, which, if removed, will reveal a moist, red base. There may be few or numerous lesions, and they may occur on any surface, but typical infections occur on the face, trunk, buttocks, and perineum.

Because of the presence of blisters, bullous impetigo is considered to be a localized form of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS; see

chapter 6). The organism is thought to be harbored in the nose and then spread to normal skin.

Diagnostics

Impetigo is often diagnosed clinically, but if the diagnosis is in question, a culture may be obtained from beneath the crust or fluid of an intact blister. A positive culture for streptococcus may be useful in patients who are later suspected of poststreptococcal nephritis.

Management

Impetigo is often treated successfully with topical 2% mupirocin (Bactroban, Centany) ointment applied three times daily until all the lesions have cleared. On occasion, if the lesions are few, it may resolve spontaneously. Topical retapamulin (Altabax) is also approved for uncomplicated skin infections caused by S. aureus. It is less effective and not approved for MRSA. Careful washing of the area with an antibacterial cleanser is suggested, whereas hydrogen peroxide is not recommended.

If the infection is widespread, or there are systemic symptoms, oral antibiotics are indicated. A 5- to 10-day course of dicloxacillin, amoxicillin clavulanate, or a cephalosporin such as cephalexin or cefadroxil will result in rapid clearing. Erythromycin is less effective and penicillin V is not indicated.

Prognosis and complications

Impetigo is a superficial infection and usually clears without scarring. Approximately 5% of nonbullous cases are caused by S. pyogenes and can be complicated with an acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. Mupirocin ointment 1% may be indicated for use in the nose b.i.d. for up to 1 year.

Referral and consultation

Most infections of this type are treated by the primary care or dermatology provider. Infections resistant to treatment or frequent recurrences may benefit from a consultation with dermatology or infectious disease for consideration of combination therapy and prophylaxis.

Patient education and follow-up

Because most impetigo occurs at a site of minor trauma, careful washing of the site with antibacterial cleanser is recommended for infection prevention. If all lesions resolve and no new ones occur, follow-up is not necessary. Failure to respond to treatment may indicate a resistant strain of organism and needs to be seen and cultured.

Folliculitis

Folliculitis is an inflammation of the hair follicle. It can be caused by infection, irritation, or physical injury. It may involve the superficial portion of the hair follicle or may be a deeper process.

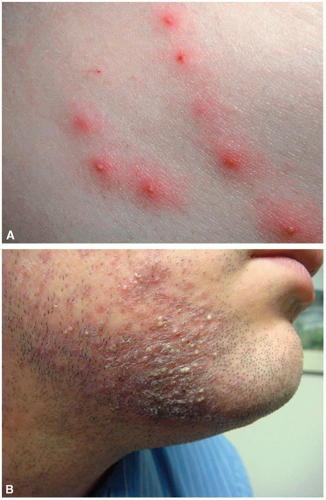

Clinical presentation

Superficial folliculitis is usually caused by

S. aureus and appears as an erythematous papule or pustule surrounding the hair. A deeper process may present initially as a red, tender nodule which may eventually develop a point in the center (

Figure 9-3). Differential diagnosis may vary depending on location.

Diagnostics

It may be important to identify the specific etiology of the folliculitis so that appropriate treatment can be rendered. Culture and sensitivities should be done if there is a fresh pustule. The most effective way to culture is to pierce the pustule with a no. 11 blade, expose the contents, and transfer them to a culture swab. An alcohol swab can be used to wipe the skin initially; however, if the procedure is done correctly, the swab should not touch the skin, just the contents of the pustule. The purpose is to eliminate contamination of the culture by swabbing the skin. A KOH prep could also be done on the contents of a pustule to rule out fungus or yeast.

Management

Superficial infection may be treated successfully with antibacterial cleansers such as chlorhexidine (Hibiclens) and topical antibiotics such as 1% clindamycin solution or gel applied b.i.d. after washing. Systemic antibiotics may be needed if there is little response to topicals but should be prescribed based on the culture and sensitivities.

Prognosis and complications

Most superficial infections resolve without scarring. Some postinflammatory discoloration may persist for some times.

Patient education and follow-up

It is important that patients understand prevention of bacterial infections, including reinfection, is largely dependent on good personal hygiene. Patients should be advised to avoid sharing personal items such as razors and towels. Athletes must make sure they are following the NCAA guidelines for play.

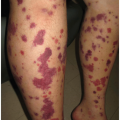

Cellulitis and Erysipelas

Cellulitis is an infection of the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Erysipelas involves the upper dermis and superficial lymphatics. Both of these conditions are common infections that result from invasion of bacteria at the site of trauma or surgical wound. Maceration of web spaces and cracks in the skin from tinea pedis create a very common portal of entry.