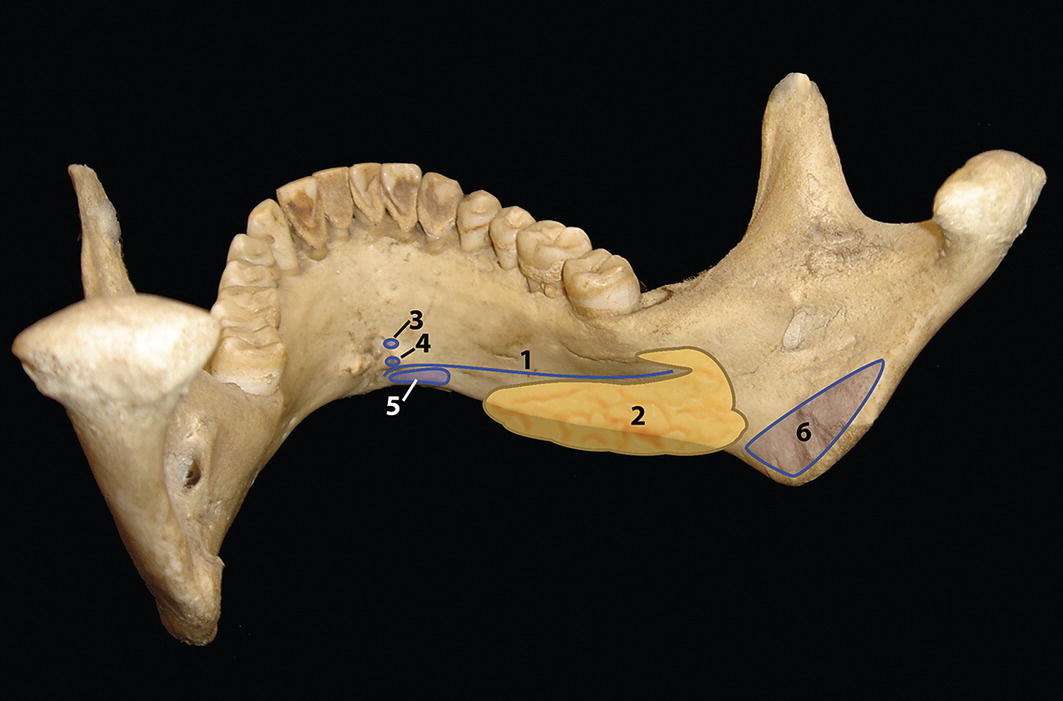

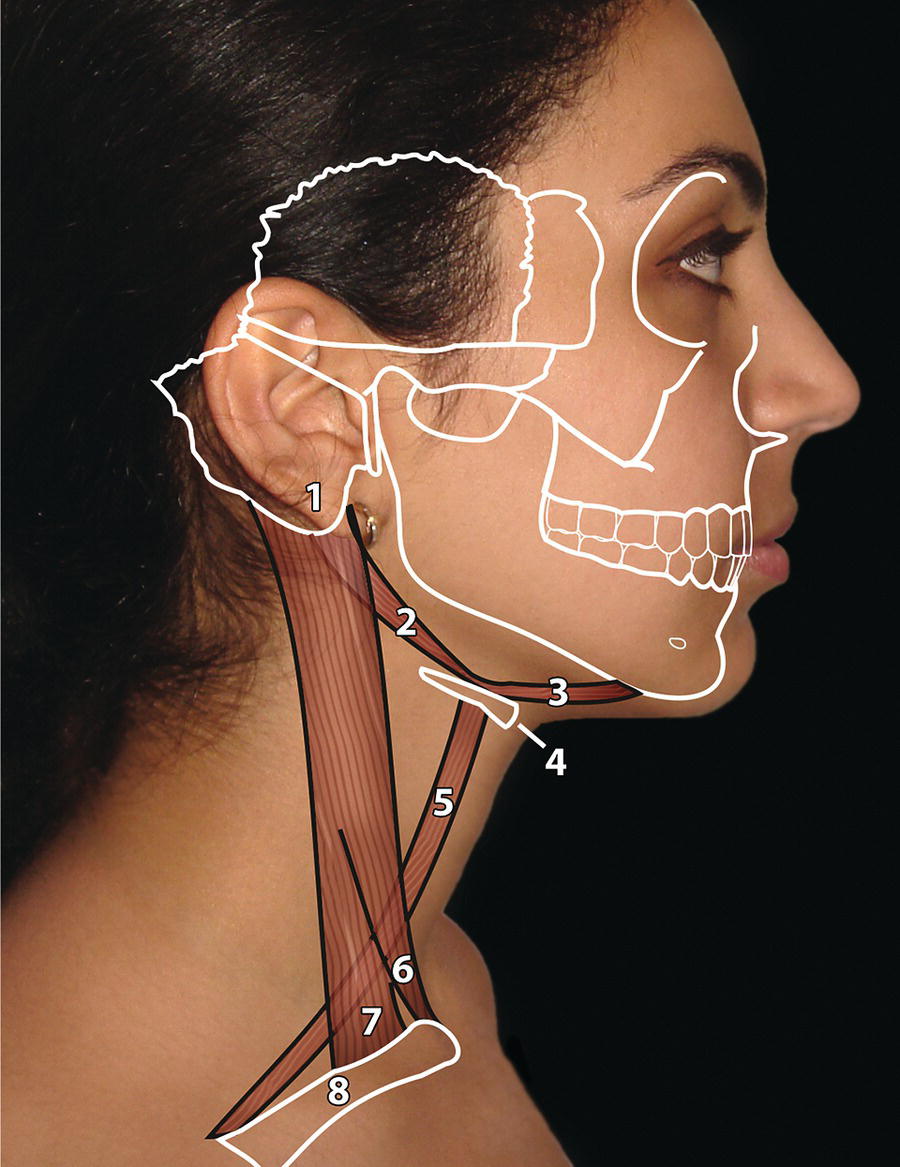

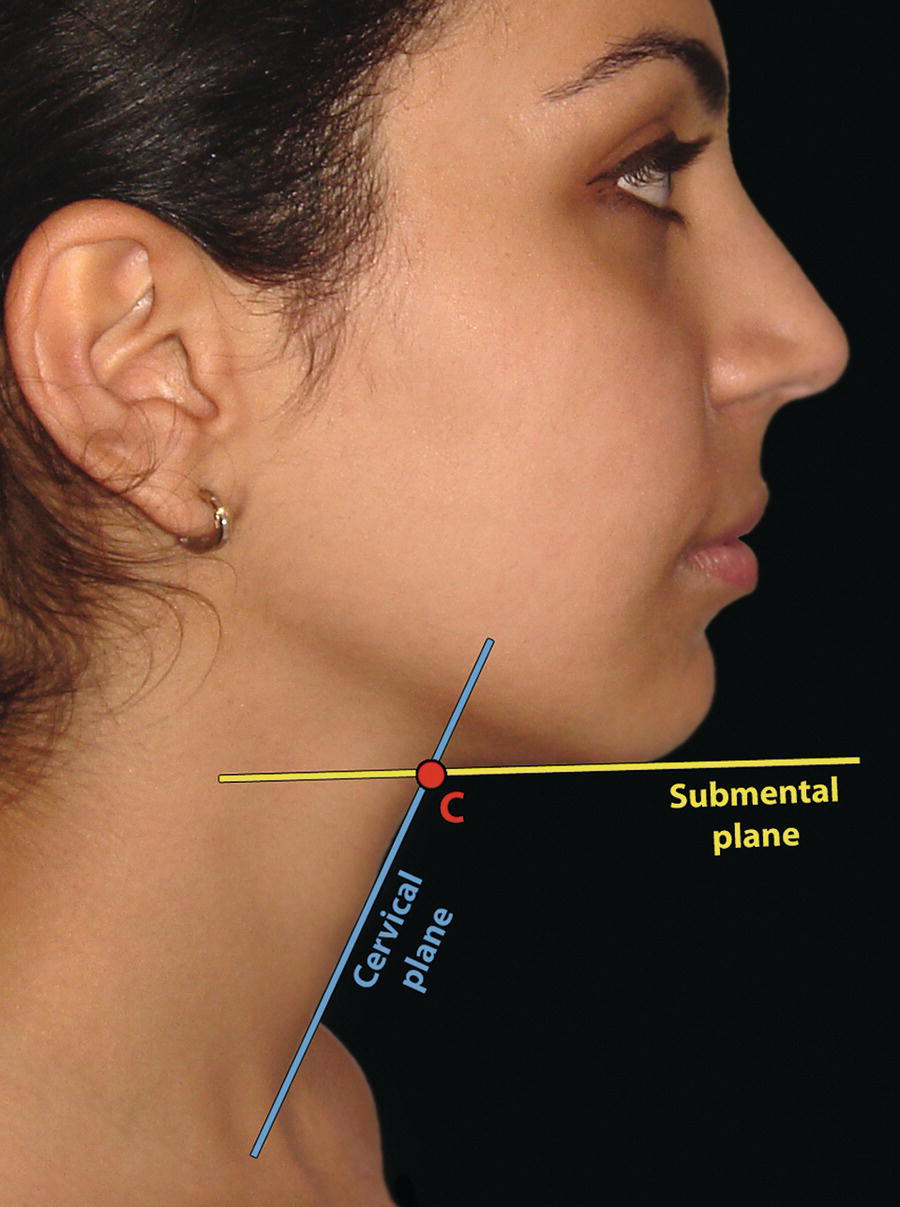

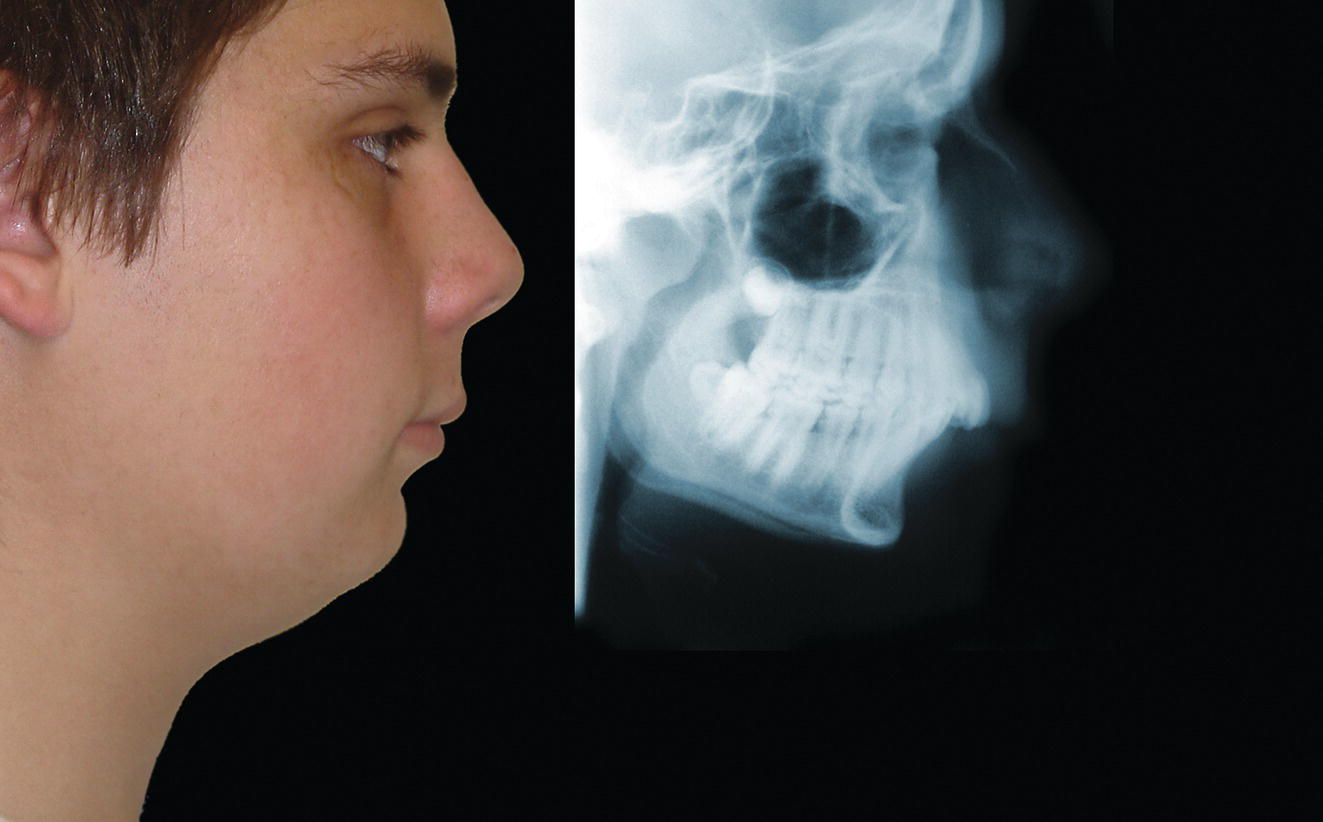

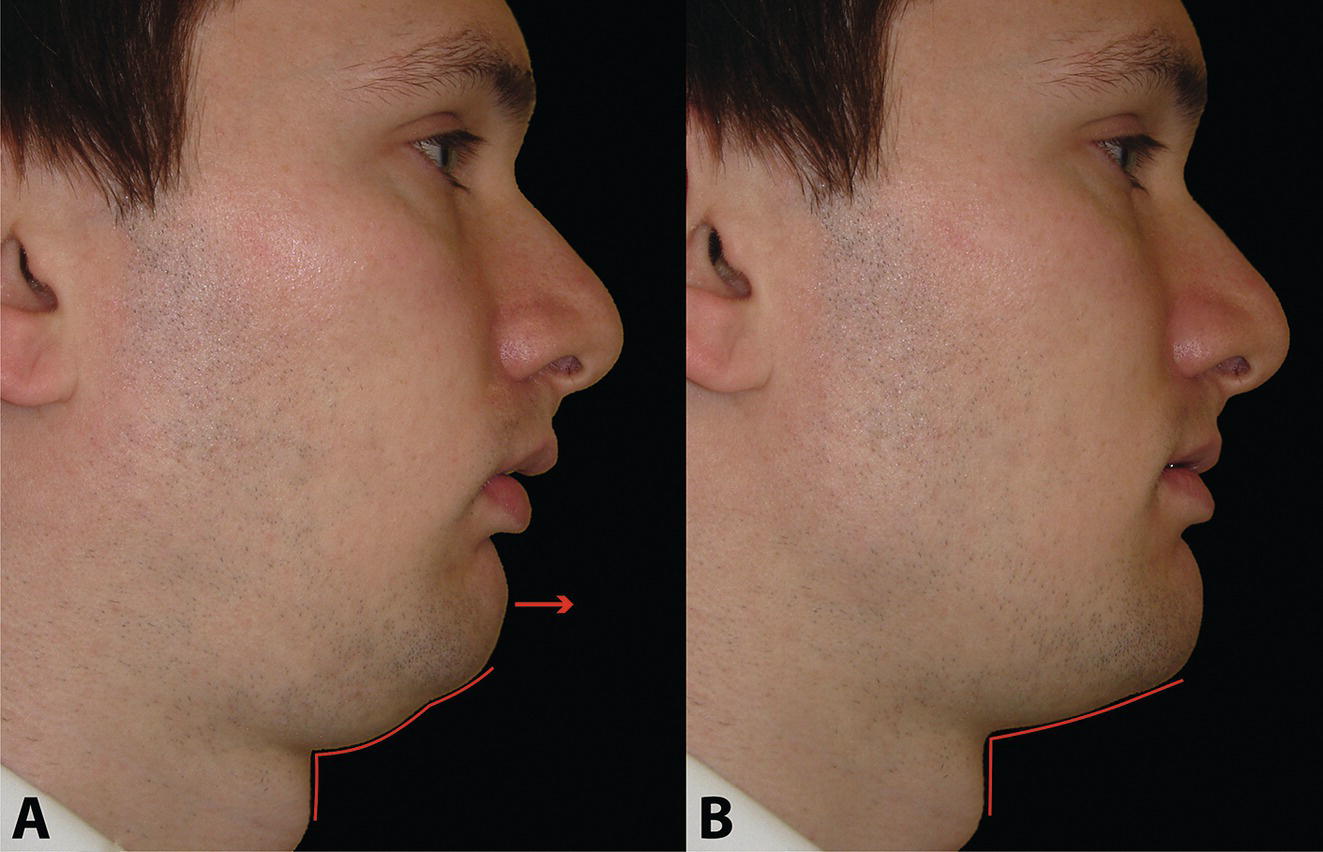

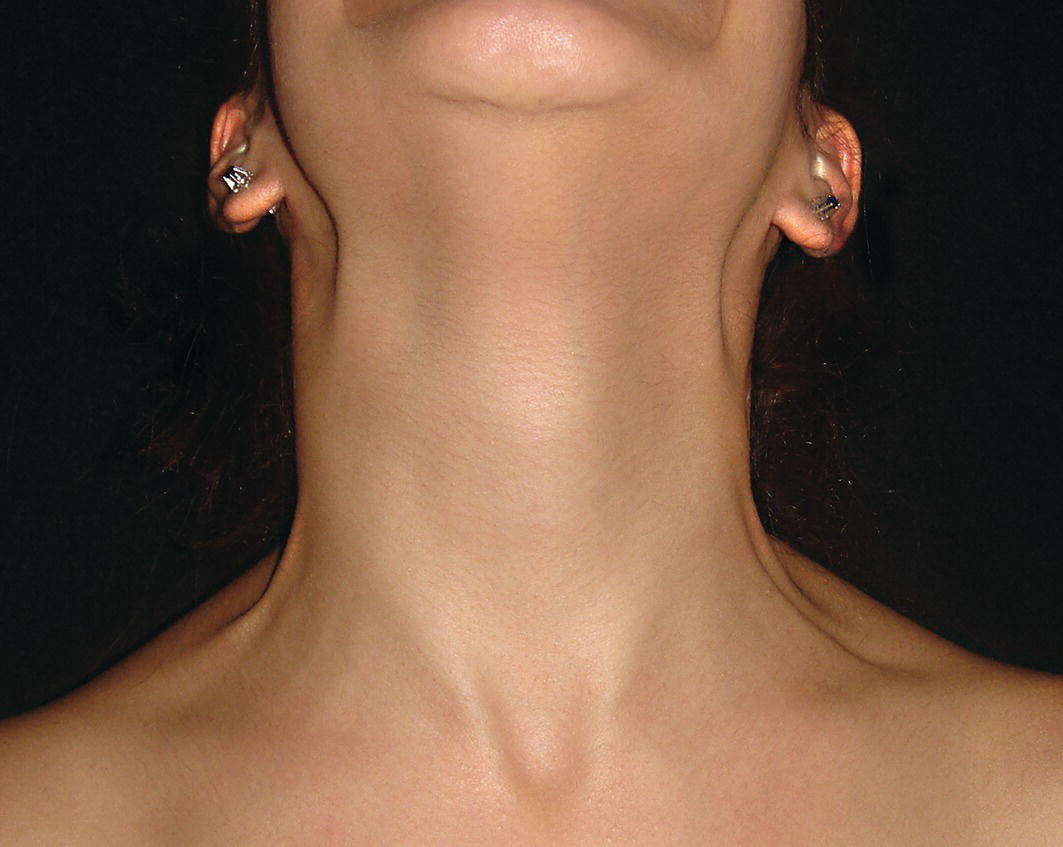

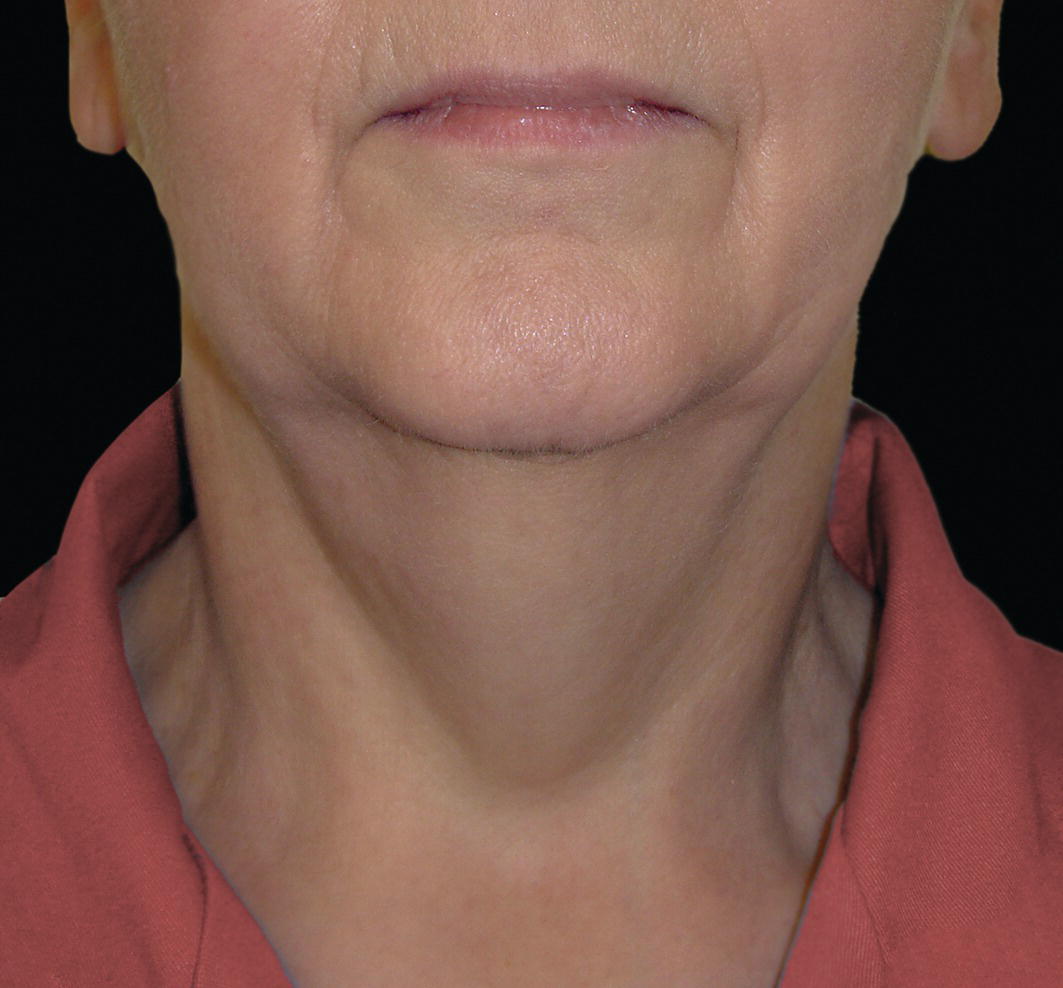

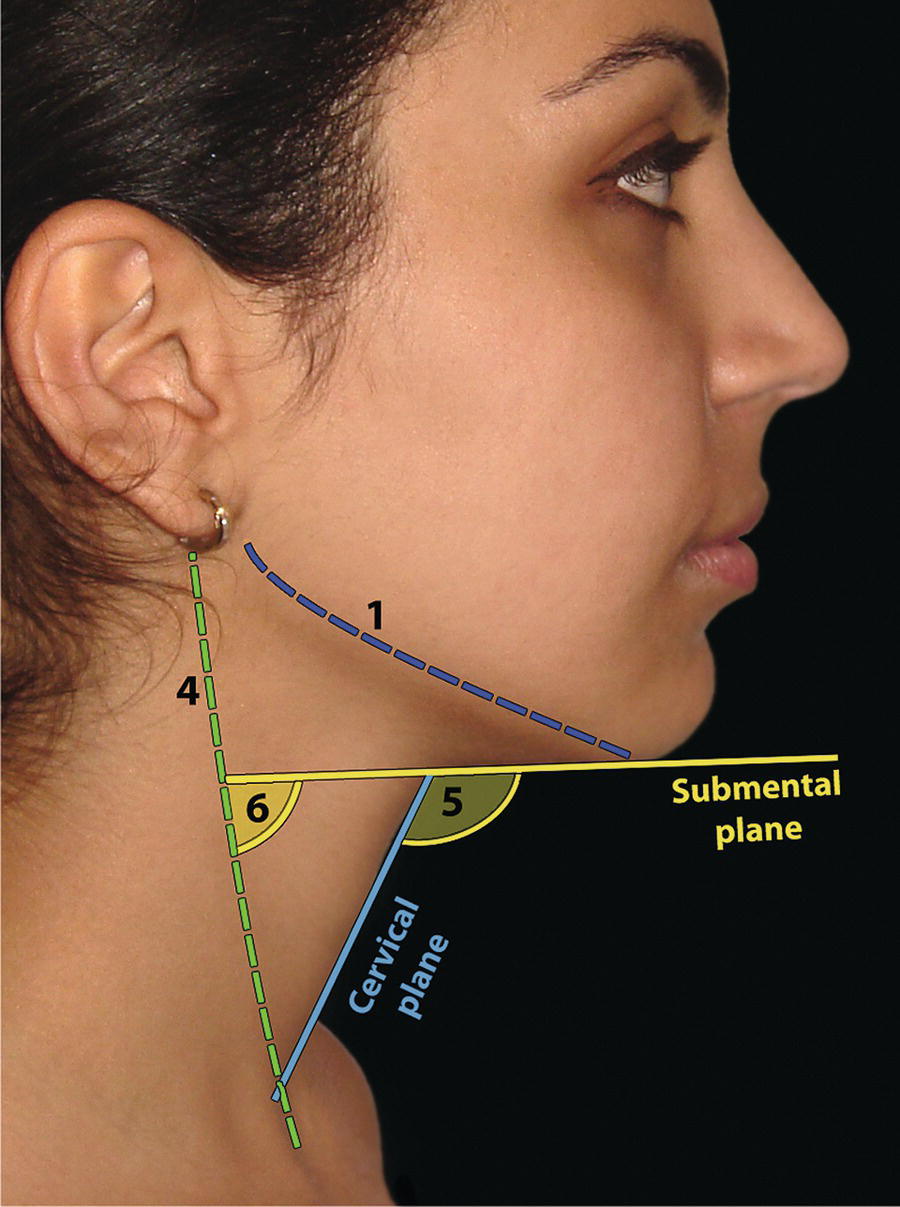

The morphology of the upper aspect of the neck and its transition with the submental region has a major impact on the aesthetics of the lower face. The anterior part of the neck extends no higher than the inferior border of the mandible. The hyoid bone is connected to the mandible by a thin sheet of muscle, the mylohyoids, which form the upper limit of the anterior part of the neck and separate the mouth from the neck. Superficially (i.e. below the mylohyoids) lies the anterior belly of digastric, while lying above it, half hidden under the mandible in the submandibular fossa, is the submandibular salivary gland (Figure 21.1). These structures are covered in by the investing layer of deep cervical fascia, which is attached to the hyoid bone and the inferior border of the mandible. The platysma muscle lies in the subcutaneous tissues. It forms a broad, flat sheet, extending from the deep fascia over the upper part of pectoralis major and the most anterior part of deltoid to the inferior border of the mandible, with some fibres reaching the lateral part of the lower lip. The sternocleidomastoid muscle forms a prominent neck landmark and may be made to stand out by turning the head towards the opposite side against resistance. The two heads of origin are from the sternum and medial one‐third of the clavicle; its attachment is to the mastoid process, which forms a readily visible and palpable bony landmark behind the lobe of the ear (Figure 21.2). Figure 21.1 Submental anatomy in relation to the mandible, with muscle attachments: Despite its importance in facial aesthetics, there is much confusion in terminology relating to the description and analysis of the submental‐cervical region. For example, the cervicomental angle has been described by perhaps half a dozen different methods, depending on the describing authority. Appropriate terminology is essential for the evaluation and accurate description of submental‐cervical aesthetics (Figure 21.3). Figure 21.2 Profile view of the face and neck with superimposed bony and muscular outlines: Cervical point (C‐point or ‘point C’): The innermost (posterior‐superior) point between the submental plane and the anterior aspect of the neck in the midsagittal plane, located at the intersection of lines drawn tangent to the submental region and the anterior neck. Submental plane: A plane or line constructed between the cervical point (C‐point) and the most inferior point on the chin (soft tissue menton, Me’). If C‐point cannot be defined, the submental plane is drawn tangent to the submental contour passing through soft tissue menton. The submental plane is referred to as the ‘throat’ plane by some authorities; the submental length (distance from C‐point to menton) is therefore sometimes referred to as the ‘throat length’. Cervical plane: A plane or line drawn tangent to the anterior soft tissue contour of the neck above and below the thyroid prominence. Figure 21.3 Submental plane, cervical plane and cervical point (C‐point). A thorough understanding of the aetiological factors involved in creating a poor aesthetic contour of the submental‐cervical region is required in order to diagnose and appropriately plan the correction of the aesthetic submental‐cervical angles and contour. The tonicity of the submental‐cervical skin, the muscular support of the neck, the isolated fatty deposits in the submental‐cervical region, the skeletal framework of the mandible and chin, and the spatial position of the hyoid bone are all important parameters in the aesthetic analysis of the submental‐cervical region. An undesirable submental‐cervical contour may result from: It is paramount that the clinical evaluation is undertaken with the patient in natural head position (NHP). Even a small degree of upward or downward tilting of the head must be avoided as it may have a profound effect on the contour of the submental‐cervical region. A number of parameters may be analysed in the clinical evaluation of the submental‐cervical region: Mandibular and/or chin deficiency in the sagittal plane, and/or posterior (downward and backward) rotation of the mandible, often secondary to vertical maxillary excess, may contribute to the undesirable aesthetic appearance of the submental‐cervical region (Figure 21.4). It is helpful to have the ‘Class II skeletal pattern’ patient posture the mandible forward to a more normal sagittal position, which will concurrently stretch the submental soft tissues. If this manoeuvre improves the submental‐cervical aesthetics visually, and tightens the submental soft tissues to palpation, then correction of the underlying skeletal discrepancy is likely to improve the submental‐cervical aesthetics (Figure 21.5). Figure 21.4 Class II jaw relationship due to mandibular deficiency and significant compensatory proclination of the mandibular incisor teeth; the submental‐cervical angle is increased. Figure 21.5 (A) Patient with Class II jaw relationship due to mandibular deficiency. (B) Posturing the mandible forward to a more normal sagittal position will concurrently stretch the submental soft tissues. Figure 21.6 Skin laxity test. The converse is also true. Surgical procedures to set back the mandible, or set down the maxilla causing posterior mandibular rotation, will tend to have undesirable consequences on submental‐cervical aesthetics (see Figure 19.22). The patient must be informed of these potential untoward consequences of orthognathic surgery, and should be advised of the possible future need for aesthetic surgical procedures of the submental‐cervical region. The laxity of the submental‐cervical skin may be evaluated by the skin laxity test: the clinician stands behind the patient and gently pulls the soft tissues upward and backward just inferior and anterior to the ear, simulating a neck lift (Figure 21.6). If the soft tissues are easily displaced upward there is increased laxity of the skin, termed redundant skin.1 If following this manoeuvre there is still submental fullness, the patient has redundant skin and excessive submental‐cervical adiposity. Reduced tonicity of the platysma may contribute significantly to submental fullness.2,3 In addition, the platysma muscle may or may not merge anatomically across the midline. Frequently, excessive submental fullness results not only from redundant skin but from the redundant medial borders of the platysma muscle that fail to meet in the midline. Increased submental‐cervical fat accumulation may be independent of generalized body fat; in some patients subcutaneous fat accumulation in this region may remain despite extensive weight loss. In younger patients the fat usually accumulates between the skin and the platysma muscle. In older patients, the fat may accumulate both deep and superficial to the platysma (Figure 21.9). The quantity of submental fat may be estimated by the submental pinch test: the submental soft tissues are gently gripped between the thumb and index finger.1 This manoeuvre should be performed with the patient both in NHP and with the head extended and contracting the platysma muscle; in this way the clinician may determine whether the submental fat is predominantly supraplatysmal or subplatysmal. Figure 21.7 Platysma view: With the head tilted slightly back in frontal view, grimacing and clenching the teeth will induce contraction of the platysma muscle. The muscular fascicles of the platysma become visible beneath the skin. Figure 21.8 Platysmal bands may be evident in repose in an ageing neck. Figure 21.9 Submental adiposity. Figure 21.10 The definition of the inferior border of the mandible is an important aesthetic parameter as it defines the demarcation between the face and neck. (Detail, Woman’s Head, Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1470–76, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.) The definition of the inferior border of the mandible, from the chin to the gonial angle, is an important aesthetic parameter, as it defines the demarcation between the face and neck (Figure 21.10). In frontal view, the transition from the upper aspect of the neck to the inferior border of the mandible has a subtle hourglass appearance, with its superior aspect being well defined by the concavity immediately below the inferior mandibular borders (Figure 21.11).1 The soft tissues of the neck normally closely adhere to the structures underlying them. Lack of definition of the inferior mandibular border may be due to increased soft tissue laxity, fat accumulation, mandibular/chin deficiency or hyoid bone sag. Figure 21.11 In frontal view, the transition from the upper aspect of the neck to the inferior border of the mandible has a subtle hourglass appearance. The submandibular salivary gland envelopes the posterior border of the mylohyoid muscle, half hidden in the submandibular fossa on the medial aspect of the mandible (see Figure 21.1). Submandibular fullness may result from an increase in size of the submandibular gland, laxity of the neck fascial layer or submandibular gland ptosis. Rhytidectomy and platysma plication address this problem indirectly by increasing the fascial support for the gland. However, patients may develop a more noticeable submandibular fullness as the removal of submental fat unmasks the ptotic gland. Partial or complete submandibular gland resection provides definite improvement of submandibular fullness resulting from glandular hypertrophy or ptosis, but may be considered too radical for a patient with a normal‐sized, ptotic submandibular gland. Guyuron et al.4 have described the basket submandibular gland suspension technique, directly supporting the gland onto the inner aspect of the inferior surface of the mandible with a strong piece of fascia. This technique helps eliminate submandibular fullness in patients with normal‐sized, ptotic glands. Resection remains the treatment of choice for the correction of glandular hypertrophy. Figure 21.12 Of the ‘six visual criteria’ of the profile view for ‘success in restoring the youthful neck’, the following are demonstrated: 1 Distinct inferior mandibular border 4 Visible anterior border of sternocleidomastoid muscle 5 Submental‐cervical (submental‐neck) angle between 105° and 120° 6 Sternocleidomastoid‐submental plane (SM‐SM) angle approximately 90°

Chapter 21

Submental‐Cervical Region

Introduction

Anatomy

Terminology

Aetiology

Aetiology of poor submental‐cervical contour

Clinical evaluation

Skeletal pattern (jaw relationship)

Morphology of the submental soft tissues

Laxity of the submental soft tissues

Submental adiposity (fat accumulation)

Inferior border of the mandible

Submandibular gland position

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree