Edward Ellis, Robert Kellman, and Emre Vural address questions for discussion and debate:

- 1.

Are there specific indications for open versus closed treatment of subcondylar fractures? Are there any contraindications to open treatment, and do they supercede the indications for open treatment?

- 2.

Does the presence of other fractures (mandible and/or midface) affect your choice of open versus closed treatment? (Is the selection of closed vs open treatment the same for unilateral vs bilateral fractures?)

- 3.

If one chooses to perform closed treatment, how long a period of MMF is required?

- 4.

What are the most important factors for success when closed treatment is used?

- 5.

What is the best surgical approach to ORIF of subcondylar fractures?

- 6.

Analysis: Over the past 5 years, how has your technique or approach evolved or what is the most important thing you have learned/observed in working with subcondylar fractures?

Edward Ellis III, Robert M. Kellman, and Emre Vural address questions for discussion and debate:

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

What are the most important factors for success when closed treatment is used?

- 5.

What is the best surgical approach to open reduction and internal fixation of subcondylar fractures?

- 6.

Are there specific indications for open versus closed treatment of subcondylar fractures? Are there any contraindications to open treatment, and do they supersede the indications for open treatment?

Ellis

I applaud this debate because I believe it is time we stopped arguing about whether condylar fractures should be treated open or closed, and instead ask which condylar fractures might have better outcomes when treated open.

I find it pejorative to come up with specific “indications” for open or closed treatment. I prefer to use the term “considerations,” for which there are many. I can think of only 1 situation in which I believe open treatment should almost always be used, and it is addressed later (condylar fractures associated with comminuted maxillary fracture[s]). However, there are other considerations that may push one toward one treatment or the other and I address these now.

However, to fully understand condylar fractures, one has to understand the adaptations in the masticatory system that occur when these injuries are treated closed or open. I refer readers to an article on this topic by Ellis and Throckmorton.

First, I believe that any unilateral condylar fracture can be treated closed, with the following prerequisites:

- 1.

The patient must have a good complement of teeth, especially posterior teeth. Without them, there is a significant loss of posterior vertical dimension and an increase in the mandibular and occlusal plane angles. The loss of posterior vertical dimension makes future prosthetic reconstruction difficult.

- 2.

The patient must be cooperative. They must wear their elastics, do their functional exercises, and return often for follow-up.

- 3.

The surgeon must be willing to see the patient often to assess treatment and alter functional therapy as necessary.

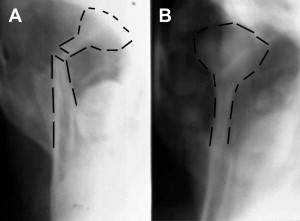

It does not matter to me whether the unilateral condylar fracture is intracapsular, condylar neck, or subcondylar. Nor does the degree of displacement matter to me. (It does not matter to me if there is a condyle. Unilateral condylectomy patients can readily be treated nonsurgically with excellent outcomes.) They can all be managed effectively if the criteria listed earlier are met. However, one must understand completely that, when one chooses closed treatment, especially those with large displacements, the neoarticulation does not translate as much as the nonfractured side. The consequence of this situation in the skeletally mature patient is that they often deviate toward the side of fracture when the mouth is opened (see Fig. 1 A in the techniques section) and they have limited lateral excursion away from the side of fracture ( Fig. 1 ). When they protrude their mandible, they also deviate toward the side of fracture. This deviation is not a failure of treatment; it is a consequence of the alteration in biomechanics secondary to the displaced condyle and the altered lateral pterygoid function. It is of no clinical consequence to the patient. That is not to say that patients treated open for unilateral condylar fractures do not do well. They usually do well, assuming that no injuries occur from the surgery to reduce and stabilize the condyle. However, one has to consider the risk/benefit ratio when deciding on treatment. If one can obtain a good occlusion, good facial symmetry, and pain-free function by treating someone closed, why should they risk the potential intraoperative and postoperative complications that are associated with open treatment?

Unlike the unilateral condylar fracture, I do not believe that I can satisfactorily treat all bilateral condylar fractures closed. Some have good outcomes; some do not. The problem is that I cannot predict which ones will do well with closed treatment and which will not. The bilateral condylar fracture, especially those that are displaced, creates a biomechanical alteration that is a challenge to the masticatory system. Bilateral loss of vertical and horizontal support from disruption of the craniomandibular articulation means that the mandible is essentially a free-floating bone, positioned only by the muscles and ligaments attached to it, and the dentition. Some patients have the neuromuscular ability to adapt to the alteration in biomechanics and others do not. A successful outcome requires the muscle coordination to be such that the patient can carry the mandible in the proper position while a new craniomandibular articulation is established. The reestablishment of a new articulation always occurs. The only question is whether the mandible will be in a favorable position at the conclusion of the process by which the neoarticulation is established. Because I cannot predict who will and will not readily adapt, I tend to treat bilateral condylar fractures, especially those that are displaced, by open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of at least one of the fractured condylar processes. However, the literature shows that perhaps only 10% of patients with bilateral condylar fractures develop malocclusions that are beyond the capability of orthodontic or prosthetic reconstruction, requiring orthognathic surgery. It is always hard to recommend that 100% of patients should undergo open treatment of their condylar fractures when 90% of them do not need it. The clinicians need to keep this in mind. Again, it is the risk/benefit ratio of open versus closed treatment that must be considered.

When a patient has the combination of a very mobile, very comminuted maxillary fracture and condylar fracture(s), I usually perform ORIF of the condylar process fracture(s). I do this because with a panfacial fracture, I choose to reconstruct the mandible first. This procedure requires that all fractures of the mandible undergo open reduction and stable internal fixation. I essentially turn a panfacial fracture into an isolated midfacial fracture. When one has an isolated midface fracture, the nonfractured mandible serves as a platform on which the maxillary arch can be positioned through maxillomandibular fixation (MMF). Because the mandible still maintains its position with respect to the cranium through the craniomandibular articulation, using the mandible provides the proper mediolateral and anteroposterior position of the maxilla. The only dimension one needs to obtain at surgery is the vertical dimension, rotating the maxillomandibular complex around the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). When the mandibular condyle is also fractured and the mandible is used to position the maxilla, one must reestablish the continuity of the mandible. Otherwise, the midface is positioned off-midline because of the tendency of the mandible to deviate to the side of the condylar fracture. That is not to say that one must always treat a panfacial fracture in this manner. The other way is to stabilize the midfacial bones, including the maxilla, using bony interfaces as guides. Once stabilized, the condylar fracture could even be treated closed. However, in my experience, it is difficult to properly position the maxilla in all 3 planes of space when the bony articulations, especially those along the anterior maxilla, are comminuted.

Another injury for which one might consider the open treatment of condylar fracture(s) is the edentulous patient. As noted earlier, if the patient has no teeth, especially posterior teeth, it is difficult to prevent the posterior mandible from moving superiorly during the formation of the neoarticulation. Even with insertion of the patient’s dentures, there is no evidence that they can prevent the tendency for loss of posterior vertical dimension. The consequence of that loss is difficulty in future prosthetic reconstruction. Treating condylar fracture(s) closed in such patients not only requires that they wear their dentures but that the dentures be secured to the jaws. Otherwise, there is no way to control the tendency for deviation of the mandible toward the side of a unilateral condylar fracture or the anterior open bite tendency in bilateral fractures. Performing open treatment in these patients allows them to go back to wearing the dentures immediately.

A discussion on this topic is not complete without discussing the skeletal maturation of the patient. This is another major consideration for me. Every study in the literature that has studied this topic suggests that skeletally immature patients have a better ability to adapt to a condylar fracture than skeletally mature patients when treated closed ( Fig. 2 ). Therefore, there is less need to perform open treatment of condylar process fractures in young patients. That is not to say that open treatment is not also effective. However, it comes back to the risk/benefit ratio. The bone in the young does not always allow secure purchase for the bone screws. The last thing one would like is loose hardware in the wound. Therefore, before performing ORIF, one has to be able to convince oneself that open treatment provides better outcomes than closed treatment.

Several considerations must be entertained before open treatment is planned. First is the ability of the surgeon to obtain an anatomic reduction and stable internal fixation. If one cannot assure oneself that one is likely to be successful in this procedure, then closed treatment might be a better option. For instance, intracapsular or diacapitular fractures of the condyle are difficult to treat open. Those surgeons who are skilled in TMJ surgery may be able to predictably perform open reduction and internal derangement of such fractures, but many surgeons find this a challenging exercise. Therefore, for most surgeons who treat maxillofacial injuries, a relative contraindication is the intracapsular or diacapitular fracture.

Another consideration hinges on the surgical approach that one might use to perform ORIF. For those surgeons who use a transfacial approach, the ability to turn the head is critical to exposing the fracture. For patients with unstable cervical spine fractures or those in halo frames, the head cannot be turned. For surgeons who use a transfacial approach, cervical spine fractures may therefore become a contraindication to open treatment. For those surgeons who use an approach that does not require the head to be turned (ie, the transoral approach), a cervical spine fracture is not a contraindication.

Another consideration for me is the patient with a condylar fracture who can still maintain a good occlusion, even when a posteriorly directed force is applied to the chin. If, after application of arch bars and ORIF of other fractures of the mandible, the occlusion is stable and reproducible to manual manipulation with posteriorly directed force applied to the chin, I see no reason to perform ORIF of the condylar process fracture. Although fractured, the fragments provide good support to the anterior mandible. These are the easiest cases to treat closed. For me, this is a relative contraindication to open treatment.

Kellman

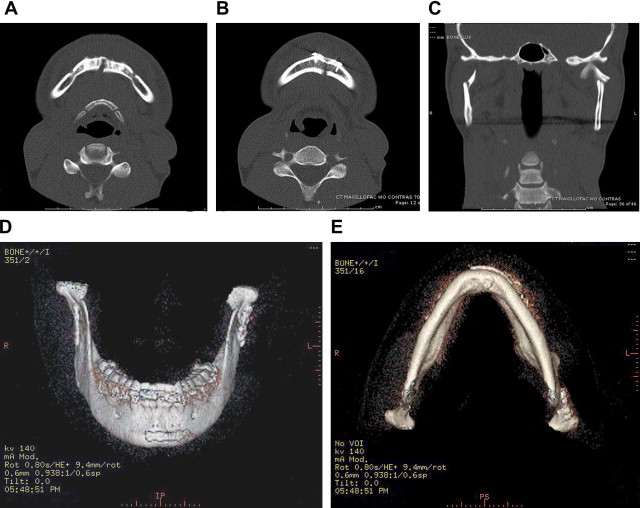

The question assumes that the diagnosis of a subcondylar fracture (or of bilateral subcondylar fractures) has been made. However, if that diagnosis is made, one must still return to the issue of diagnosis. One of the first controversies that we face as clinicians is how to evaluate these injuries. Whereas some surgeons are satisfied with a panoramic tomographic radiograph (orthopantomogram), others suggest the benefit of plain films of the mandible, because the Towne view provides an excellent view of the vertical rami of the mandible, allowing assessment of angulation of the condylar segment, as well as assessment of the vertical height of the ramus-condyle unit. Schubert and colleagues have found that the combination of computed tomography (CT) scans and orthopantomograms provides the most complete diagnostic evaluation of mandibular fractures, and Lee and colleagues advocate obtaining both axial and coronal CT views of the ramus/condyle unit when subcondylar fractures are suspected. These views show alterations in vertical height and angulation as well as rotation of the condylar segment. CT also provides for better assessment of comminution, although it often underestimates the extent of comminution.

Although the various radiographs provide for excellent analysis of the fracture, the most important assessment is clinical. If the patient is able to open and close normally or near-normally and achieve their normal occlusal relationship easily, then limited intervention is generally warranted. A soft diet along with early physiotherapy usually provides a satisfactory result. However, if there is a shift in the chin point to one side or the other or if there is visible foreshortening of one side of the mandible (and therefore an alteration in facial appearance), or widening of the face because of malposition of the bone, then additional options should be discussed with the patient. Similarly, if the patient has difficulty bringing the teeth into a premorbid occlusal relationship, additional intervention is warranted.

Experience has shown that most subcondylar fractures of the mandible can be successfully managed using nonopen techniques. This statement does not mean that so-called closed techniques reduce subcondylar fractures. They do not. However, they do manage the occlusion, and most patients achieve what have long been considered satisfactory results using this approach. For me, closed management (I am not saying closed reduction) entails the application of arch bars to the upper and lower dentition followed by the use of limited elastic traction (commonly referred to as training elastics) to gently pull the dentition into a premorbid relationship and permit function, so that the patient can open and close the mouth. This strategy also allows for early physiotherapy. The elastics are left in place until the patient can maintain their premorbid occlusal relationship without them. This procedure requires close follow-up, particularly because the option of reconsidering open reduction for those patients for whom this approach is not working well should be considered earlier rather than later (preferably within 1 to 2 weeks). Probably the single biggest controversy in the management of these fractures is the question of when open reduction should be used, because some surgeons perform open reduction freely on most if not all fractures, whereas others use open reduction rarely if ever, and most fall somewhere between.

Open reduction should be performed when a reasonable occlusal relationship cannot be achieved, even under general anesthesia with muscle relaxation. It should also be considered for those patients who are bothered by the alteration (or, in discussion with the patient, the potential alteration) in their cosmetic appearance that results from the change in the mandibular shape. The presence of edema can make this alteration difficult to determine early on, and sometimes the likelihood or potential of these changes developing is part of the discussion with the patient, because the final appearance with and without surgery may be difficult to predict precisely in a timely fashion that allows for timely repair. The surgical repair of subcondylar fractures becomes more difficult as time passes, so it is often necessary to make a surgical decision before the swelling has gone down sufficiently for the patient to decide based on the appearance.

Open reduction can be performed transcutaneously with direct exposure of the fractured fragments, or it can be performed via a transoral approach, typically with the aid of an angled endoscope for better visualization of the fragments when using the transoral approach. The choice of surgical approach is yet another controversy. Once the bone fragments are reduced, 1 or 2 titanium miniplates are generally applied across the fracture, although the size, strength, and number of plates required to obtain a good result are not clear and may even vary from patient to patient. When open reduction is used, I still prefer to apply arch bars and use the same postoperative approach that I use with closed management (ie, loose training elastics and physiotherapy).

As noted earlier, the foremost reason to perform open reduction of a subcondylar fracture of the mandible is the inability to reduce the occlusion, particularly if this inability persists under general anesthesia with muscle relaxation. If the patient cannot come into occlusion themselves, the surgeon may still be able to compensate for this under anesthesia, and if preferred by either the patient or the surgeon, closed management with training elastics and physiotherapy may still be attempted. However, when the occlusion cannot be reduced under anesthesia, a poor outcome is almost assured, and therefore open reduction is warranted to try to achieve a better functional result. Two recent prospective studies have suggested better outcomes when open surgical reduction and repair are used, although there are conflicting data as well. The study by Eckelt and colleagues is particularly worthy of careful review, because the randomization was impressive, so that severity of injury was not used to determine the treatment, unlike the situation with almost all of the retrospective studies, which showed little difference regardless of treatment category. (In most of these reviews, the results of the open and closed treatments were similar despite the fact that the more severe fractures with more severe displacement/dysfunction were generally in the open groups.)

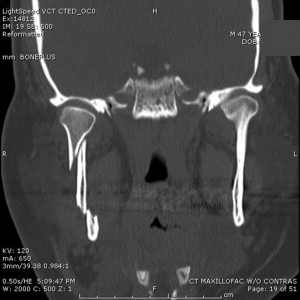

Cosmetic deformity is also an important consideration. When there is significant foreshortening on radiograph (>1 cm) ( Fig. 3 ), the change in the patient’s appearance may be apparent, although the amount of overlap that correlates with a noticeable cosmetic deformity has to my knowledge never been studied. However, it may be necessary to discuss the risk of cosmetic deformity with the patient, even when it is not yet apparent because of swelling. Because open reduction is not without its own attendant risks, the surgeon needs to be careful to inform rather than lead the patient.

The presence of midfacial fractures, particularly when severe enough to make determination of facial height challenging, should be considered an indication for open reduction. In this situation, the reestablishment of the vertical height of the ramus of the mandible serves as a guide to the midfacial position. This situation leads directly to the next question.

When considering contraindications to open repair, any other medical condition that would contraindicate proceeding with anything other than life-or-death surgery should similarly be considered a contraindication. However, in terms of maxillofacial contraindications, I would expected failure, such as might be predicted with very high or severely comminuted fractures would be in this category. These are relative contraindications, though, and if there is a particular clinical indication for open reduction, it should probably supersede a contraindication in this category. However, just as the evolution of treatment from closed to open repair of subcondylar fractures is progressing, the same might be said for fractures of the condylar head. Most surgeons, particularly in the United States, see few if any indications for repairing condylar head fractures, but there is a small but increasing group of European surgeons who believe that open reduction of condylar head fractures yields better outcomes. The absence of dentition makes closed management difficult, so if there is displacement or foreshortening that necessitates treatment, an open approach should be entertained. Although most surgeons rarely open subcondylar fractures in children younger than 14 years, age younger than this is not considered an absolute contraindication.

Vural

Although there is almost universal consensus on the management of pediatric subcondylar fractures, which are almost exclusively treated with a closed approach, treatment of subcondylar mandibular fractures in the adult population probably forms one of the most controversial topics of discussion in maxillofacial trauma. Therefore, it is difficult to establish absolute indications or contraindications for open versus closed management of these fractures. Use of an endoscopic approach in the treatment of subcondylar fractures is an exciting recent advance. However, the question of whether these fractures need to be managed closed or open still exists. I believe that both approaches have a role in the management of subcondylar fractures and each of these approaches may serve better than the other in certain conditions.

The goal in the treatment of subcondylar fractures should be providing the patient with a satisfactory occlusion with the least possible discomfort and limitation of movement in the mandible. However, the jury is still out on deciding which approach is the best to accomplish this goal, because there are no high-quality published data comparing of the outcomes of closed, open, or endoscopic management of subcondylar fractures. A recent Cochrane review performed by Sharif and colleagues indicates that the decision of which is the best approach in subcondylar fractures may not be made based on current evidence. Another recent study performed by Nussbaum and colleagues, which involved a meta-analysis of published data on condylar fractures in adults, revealed that most of the parameters showed no difference between open and closed approaches, although some parameters favored one approach over another. As stated in these 2 articles, there are numerous shortcomings in the presentation of the published data on subcondylar fractures; such as lack of uniformity in patient populations, bias in the selection of approach, and subjective evaluation of certain parameters. When we present data on occlusion for open and closed approaches, do we really know how the occlusion was for any given patient before the event causing the fracture? Do we pick and choose what we plate and what we do not plate? And, do we really know if one particular patient treated with one approach would do the same, better, or worse if the other approach was used?

An exhaustive literature review in this topic reveals both significant and nonsignificant differences between open and closed approaches, for almost all parameters, such as occlusion, excursion, pain, interincisal opening, protrusion, or deviation. Considering all these, it is impossible to establish absolute indications for each treatment approach. Fracture of the subcondylar region is an unfortunate event, and both good and bad outcomes are possibilities regardless of the approach chosen. Multiple other factors are involved in obtaining the final outcome (satisfactory or unsatisfactory) in any given patient, in addition to the selected management approach. The status of the patient’s dentition, compliance, bone stock quality, age, comorbid conditions, occlusal relationship before the event causing fracture, and presence of additional maxillofacial fractures, infection, or other accompanying life-threatening issues such as intracranial injuries are just a few. Therefore, it is more appropriate to talk about personal preferences rather than indications/contraindications of open versus closed treatment.

Nonetheless, performing open or endoscopic reduction/fixation in a subcondylar fracture may be contraindicated if the patient is not a candidate for general anesthesia, does not wish to undergo open or endoscopic surgery, or has other life-threatening issues to be resolved. The benefits of attempting rigid fixation of high fractures such as intracapsular fractures or condylar head fractures are questionable and may not outweigh the risks. Therefore, rigid fixation may be considered contraindicated in these fractures.

Does the presence of other fractures (mandible or midface) affect your choice of open versus closed treatment? (Is the selection of closed vs open treatment the same for unilateral vs bilateral fractures?)

Ellis

I addressed these issues fully in my first response. To summarize, I believe that any unilateral condylar fracture can be treated closed, with several prerequisites. Unlike the unilateral condylar fracture, I do not believe that I can satisfactorily treat all bilateral condylar fractures closed. Some have good outcomes; some do not. The problem is that I cannot predict which ones will do well with closed treatment and which will not. It is always difficult to recommend that 100% of patients should undergo open treatment of their condylar fractures when 90% of them do not need it. Clinicians need to keep this in mind. Again, the risk/benefit ratio of open versus closed treatment must be considered.

Kellman

As noted earlier, the presence of severe midfacial fractures usually requires direct (open) repair of displaced subcondylar fractures. When the midface is comminuted, the mandible serves as a template for positioning of the alveolus, thereby determining the relationship of the maxillary dental arches to the remainder of the face and skull. Foreshortening of the mandibular height as a result of loss of continuity of the ramus-condyle unit positions the maxillary dental arches superiorly, with resultant foreshortening of the midface (in essence, an accidental maxillary intrusion).

One should also consider the presence of other mandible fractures. In particular, the presence of symphyseal/parasymphyseal fractures of the mandible should be considered, because the combination of these fractures is a setup for widening of the mandible with lingual splaying of the symphyseal fracture(s). It is difficult to adequately reduce the symphyseal region first, and therefore, I prefer to open and repair the subcondylar fracture(s) first, before applying the final fixation to the symphysis ( Fig. 4 ). For this type of combination, bilateral subcondylar fractures are more difficult than unilateral, although widening can result with a unilateral fracture as well.