High volume—the most common skin conditions seen in clinical practice;

High morbidity—skin disease that is contagious or can impact quality of life or the community; and

High mortality—life-threatening conditions that require prompt recognition.

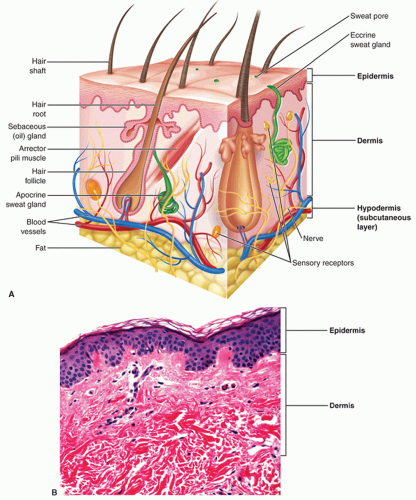

thickness according to the body location. The hypodermis provides a layer of protection for the body, thermoregulation, storage for metabolic energy, and mobility of the skin.

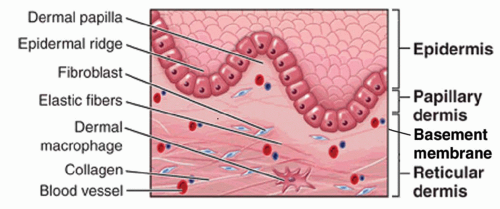

hypohidrosis. Eccrine glands maintain an important electrolyte and moisture balance of the palms and soles.

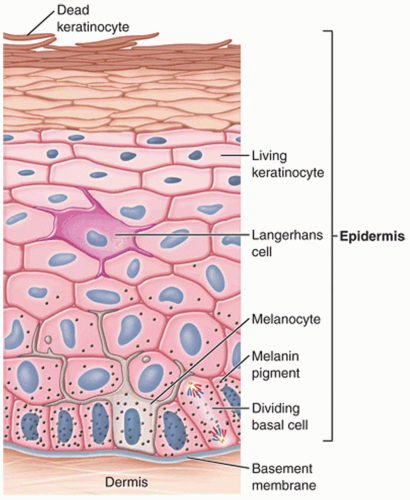

TABLE 1-1 Strata of the Epidermis | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree