14 Stress Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Nonsurgical Management

THE BLADDER DIARY: A VALUABLE CLINICAL TOOL

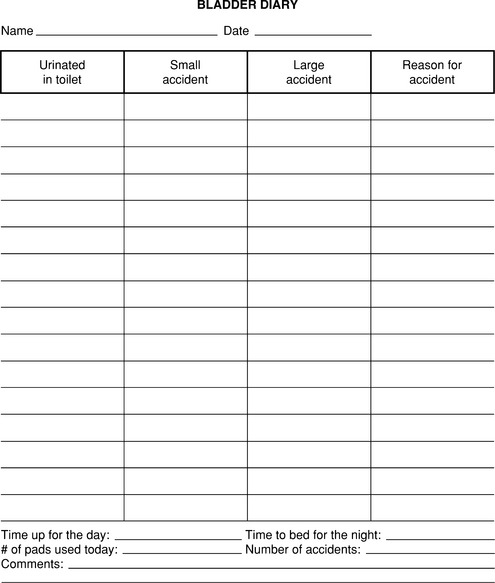

Before initiating nonsurgical treatment for incontinence, the patient is advised to complete a bladder diary for 5 to 7 days. At a minimum, the patient should record the time, volume, and circumstances of each incontinent episode (Fig. 14-1). The bladder diary assists the clinician in determining the type and severity of urine loss and in planning appropriate intervention. Using the diary, the circumstances of incontinence can be reviewed with the patient and instructions given that are specific to the patient’s situation. During treatment, the number of incontinent episodes can be monitored to determine the efficacy of treatment and to guide further intervention. Asking the patient to record the times she urinates during the day and night is useful. This can identify women who may benefit from more frequent urination to avoid a full bladder, especially during physical activity. It may also reveal cases in which voiding frequency is excessive and may be contributing to reduced bladder capacity and urgency. These women may be targeted for interventions like bladder training that focus on increasing voiding intervals and bladder capacity.

BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTION: PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING AND EXERCISE

Pelvic floor muscle training and exercise are the foundation of behavioral treatment for SUI. Kegel (1948), a gynecologist, first popularized it in the late 1940s. He asserted that women with stress incontinence lack awareness and coordination of the pelvic muscles; with training and improved strength, stress incontinence can be prevented (Kegel, 1948, 1956). Through the years, this intervention has evolved both as behavior therapy and physical therapy, combining principles from both fields into a widely accepted conservative treatment for stress incontinence.

Literature on outpatient behavioral treatment with pelvic muscle training and exercise has demonstrated that it is effective for reducing stress, urge, and mixed incontinence in most patients who cooperate with training. Behavioral treatments have been recognized for their efficacy by the 1988 Consensus Conference on Urinary Incontinence in Adults (1989) and by the Guideline for Urinary Incontinence in Adults developed by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) (Fantl et al., 1996). Although the majority of women are not cured with this approach, most can achieve significant improvement.

Teaching Daily Pelvic Floor Muscle Control

The goal of behavioral intervention for stress incontinence is to teach patients how to improve urethral closure by contracting pelvic floor muscles during physical activities that cause urine leakage, such as coughing, sneezing, or lifting. The premise is that deliberate muscle contraction will increase intraurethral pressure and prevent urine loss caused by the brief rise in bladder pressure. Using biofeedback or other teaching methods, patients are taught to identify the pelvic muscles and to contract and relax them selectively (without increasing intra-abdominal pressure).

Biofeedback is a teaching technique that helps patients learn by giving them immediate feedback of their bladder or pelvic muscle activity. Kegel (1948) introduced a biofeedback device he called the perineometer, consisting of a pneumatic chamber that was placed in the vagina and a handheld pressure gauge that registered increased vaginal pressure generated by pelvic muscle contraction. This provided immediate visual feedback to the woman learning to identify her pelvic muscles and monitoring her practice.

Once patients learn to properly contract and relax selectively the pelvic muscles, a program of daily exercise is prescribed. The purpose of the daily regimen is not only to increase muscle strength, but also to enhance the skill of using the muscles through practice. The optimal exercise regimen has yet to be determined; however, good results are generally achieved using 45 to 50 exercises per day. To avoid muscle fatigue, the exercises should be spaced across the day, usually in two to three sessions per day (Fig. 14-2). Patients generally find it easiest to at first practice their exercises in the lying position. Encouraging them to practice sitting or standing as well is important, so that they become comfortable using their muscles to avoid accidents in any position.

Using Muscles to Prevent Urge Accidents: Urge Suppression Strategies

Traditionally, pelvic floor muscle training and exercise were used almost exclusively for stress incontinence. However, voluntary pelvic muscle contraction can also inhibit detrusor contraction. Therefore, pelvic muscle training is now frequently used as a component in the behavioral treatment of urge incontinence as well. In addition to using pelvic muscles to occlude the urethra, patients learn to use pelvic muscle contractions and other urge suppression strategies to inhibit bladder contraction. Further, patients are taught a new way to respond to the sensation of urgency: Instead of rushing to the toilet, which increases intra-abdominal pressure and exposes patients to visual cues that can trigger incontinence, patients are encouraged to pause, sit down if possible, relax the entire body, and repeatedly contract pelvic muscles to diminish urgency, inhibit detrusor contraction, and prevent urine loss. When urgency subsides, patients are to proceed to the toilet at a normal pace.

Behavioral training for urge incontinence has been tested in several clinical series using prepost designs. Mean reductions of incontinence range from 76% to 86%. In controlled trials using intention-to-treat models by Burgio et al. (1998), 2002), mean reductions of incontinence episodes range from 60% to 80%.

Adherence and Maintenance

The long-term effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle exercise in treating incontinence symptoms is still unknown because most studies follow patients for 1 or 2 years only. One study by Glazener et al. (2005) showed that, after 6 years of a postpartum pelvic muscle exercise program, initial improvements in SUI did not persist, and incontinence was similar to the control group. Only half the women were still performing the exercises.

Electrical Stimulation

Pelvic floor electrical stimulation (PFES) has been used for the treatment of urinary incontinence since 1952 (Huffman et al., 1952). In this original study, PFES was added to pelvic muscle exercises to treat stress incontinence in women who had failed treatment with exercise alone. Seven of 17 women were cured. Fifteen years later, PFES was reported by Moore and Schofield (1967), using a vaginal probe, and has since become widely used.

Research has demonstrated the efficacy of PFES compared to sham PFES (Sand et al., 1995; Yamanishi et al., 1997). Some evidence also shows that PFES yields similar results to pelvic muscle training (Hahn et al., 1991), although Bo et al. (1999) found pelvic muscle exercise to be superior. Several studies have combined PFES with various methods of pelvic muscle training and exercise and reported successful outcomes. One small study by Blowman et al. (1991) compared pelvic muscle exercise and exercise augmented with PFES in 14 patients and found that the addition of PFES improved outcomes as measured with bladder diaries and muscle strength. In another study by Sung et al. (2000), pelvic muscle exercises, augmented with both PFES and biofeedback, produced greater improvements compared with pelvic muscle exercises alone; however, the effect of PFES cannot be isolated from biofeedback. A third study by Goode et al. (2003) found that PFES did not significantly enhance the outcome of pelvic muscle training with biofeedback. Thus, although PFES shows promise in the treatment of stress incontinence, the role of electrical stimulation in combination with behavioral treatment with pelvic floor muscle training and exercise has not been clearly defined.

BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTION: BLADDER TRAINING

Bladder training is a behavioral intervention developed originally for urge incontinence. In its earliest form, known as bladder drill, it was an intensive intervention often conducted in an inpatient setting. Patients were placed on a strict voiding schedule for 7 to 10 days to lengthen the interval between voids and to establish a normal voiding interval. Cure rates in women ranged from 82% to 86% (Frewen et al., 1979, 1982). Bladder training is a modification that is conducted more gradually in the outpatient setting.

Cure rates ranging from 44% to 90% have been demonstrated using outpatient bladder training or a mixture of inpatient and outpatient intervention. The first randomized trial of bladder training was reported by Fantl et al. (1991) and demonstrated an average 57% reduction of incontinence in older women. Interestingly, the training not only reduced urge incontinence, but also stress incontinence. The presumed mechanism for improving stress incontinence is that regular voiding helps avoid situations in which the bladder is full, making the patient less vulnerable to urine loss during physical activities. It is also possible that training leads the patient to greater awareness of bladder function, and postponing urination increases the use of pelvic muscles.

WEIGHT LOSS AND INCONTINENCE

Obesity is one of the major chronic health problems in America today. It contributes to more than 300,000 deaths per year and is associated with increased risk for hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, cancer, arthritis, respiratory disease, and depression. Over 50% of American women are currently overweight (body mass index [BMI] = 25–30 kg/m2) or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) (Mokdad et al., 2001).

Obesity is a strong risk factor for incontinence. Data from the Heart and Estrogen-Progestin Replacement Study (HERS: 2763 women with coronary artery disease) and the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF: 9500 women at risk for fractures) revealed that of those complaining of incontinence, 65% to 75% were overweight or obese (Brown et al., 1996, 1999). Each five-unit increase of BMI was associated with a 60% increase in the risk of daily incontinence. Furthermore, obesity had the largest attributable risk for daily incontinence compared with other risk factors. Because many obese women are at risk for morbidity secondary to other chronic diseases, in addition to incontinence, weight loss should have a tremendous impact on quality of life.

ESTROGEN AND STRESS INCONTINENCE

Large cohorts of women evaluated subjectively have had significant symptomatic improvement using vaginal estrogen. However, randomized controlled trials, with oral estrogen alone or combined with progestin, for the most part, showed no significant difference subjectively or objectively in SUI symptoms between groups. In one study by Grady et al. (2001), daily oral estrogen plus progestin was associated with worsening urinary incontinence. A recent questionnaire analysis of the Nurse’s Health Study participants by Grodstein et al. (2004) noted a significantly increased risk of developing urinary incontinence with use of postmenopausal hormone therapy. However, in randomized trials, ERT (oral and vaginal) combined with other therapies such as the α-adrenergic agonist, phenylpropanolamine (which is currently off the market due to increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke), pelvic muscle exercises, and surgery, have shown some benefit.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree