STRATEGIES FOR STUDYING

TAKING AN INVENTORY

What SHOULD I know versus what DO I know?

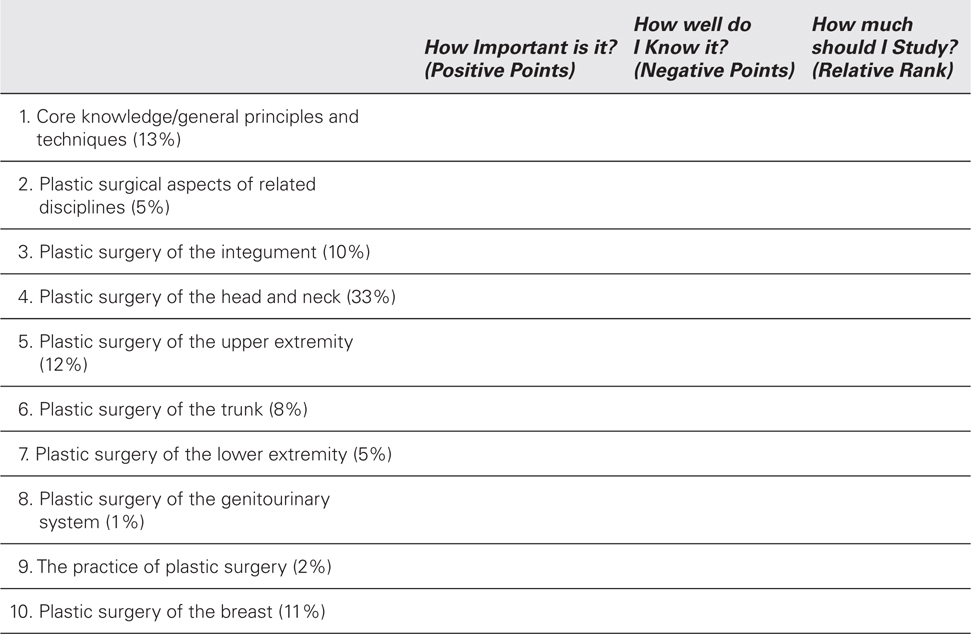

High-stakes examinations are made from blueprints. Within the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS), each specialty board sets forth the content of the specialty’s examination in a format that emphasizes the importance of the material and then a test committee creates questions to fit the blueprint. The American Board of Plastic Surgery (ABPS) provides an approximate blueprint to you. Outline of the content of the certifying and recertifying examinations can be obtained from the ABPS web site directly at www.abplsurg.org and selecting the “Written Examination” link on the left-hand menu. Since the last version of this book, the ABPS has made the blueprint more explicit. The 10 areas of assessment are listed with the approximate weight of the area in the table below. I encourage you to go to the web site as well as the ABPS has further subareas listed under each of the major areas below and has a very detailed outline of the materials in a document labeled “Written Exam and MOC Content Outline.”

How do I figure out what is important for me to study?

Each residency training experience is unique, making the generalization of importance of topics somewhat difficult for an individual to determine. For example, if you went to a program with a burn unit, you probably had lots of burn experience and think it is pretty important in the national curriculum but if your program did not have a burn unit you might think that burn care is fairly insignificant. Look at how national sources value topics—how much time and how many pages are devoted to the various topics? Some sources for an idea of the national curriculum in plastic surgery education include Selected Readings in Plastic Surgery, the Plastic Surgery Education Foundation (PSEF) Core Curriculum, and general plastic surgery texts.

PLANNING YOUR ATTACK

Now that you have decided what you should know, ask yourself how well you know it. One way of organizing things is to create a table with what you know against what you need to know, like the one below. Rank importance from 1 (not so important) to 10 (very important) in the how important (first) column. Rank how good you feel about the topic from 1 (I don’t know much) to 10 (I know this cold). Subtract the second column from the first and a rank list for study should appear.

For example, if you decided that plastic surgery of the upper extremity was very important (10) to you and you knew very little (3) then the number for that topic would be 7. If you decided practice of plastic surgery was not important (1) but you were a psychology major in college and know a lot (10), the rank would be a very low negative (–9). By assigning a rank and deciding what to study in this manner, you will avoid the pitfalls of studying what you like to study at the exclusion of what you need to study.

If you are repeating the examination, review your last test performance and see in which areas you scored well and poorly. Use this information to help you fill in the above table. If you have had problems with standardized tests in the past, or this test in particular, figuring out what impedes you is important. Several factors may be in play:

1. You think you know the material, but you don’t. Review the content outline of the examination and make sure you know these topics. If there are areas that you failed to study or were not emphasized during your residency, go back to original text sources to learn them. Books such as this one can help remind you of something you have learned in the past or give you a pearl or two. If you have never learned the topic, primary sources should be used.

2. It’s too much to memorize. To get to medical school, you succeeded on many tough standardized tests (think SAT and MCAT). However, the depth and breadth of knowledge measured on board examinations is beyond memorization. Adult learning theory posits that adults learn by making connections with previous experiences and knowledge—that is, we learn in context. For example, when reading a journal article about a new technique, you are likely to compare it to a technique you already know so your mind picks up the similarities and differences rather than starting at the beginning of the new technique.

3. You may have genuine testing problems. Lloyd Bond lists test anxiety, lack of sophistication, lack of automaticity, and test bias as barriers. His summary is a quick and interesting read (http://www.carnegiefoundation.org/perspectives/my-child-doesn’t-test-well). Bias and sophistication are unlikely candidates for barriers at this level of education. Test anxiety and lack of automaticity are likely culprits. For disabling anxiety, seek professional life coaching or psychological services. Automaticity can be enhanced by learning the material deeply and practicing with questions to improve speed of recalling information.

4. You may have subtle learning differences. Full neuropsychological evaluation may be beneficial to find strategies that are appropriate. Some examples of learning differences include auditory processing disorders and dyslexia.

SETTING YOUR GOALS

You know the date of your examination, you know what you need to study, you know yourself and your ability to take tests, so decide that your goal is to pass the examination. The board only awards the grade of pass or fail; there is no indication on your certificate of the percent correct. If you do not think you can get all of your studying done before the test, do not expect to pass. If you were present and studying throughout your residency, much of the test information should already be incorporated into your plastic surgical soul. The qualifying examination should be a matter of reminding yourself of the details and brushing up on areas that present rarely or that were not the forte of your program. For information that you may be learning for the first time because of the structure of your residency, spaced repetition with periodic assessment has been suggested as a way to retain information up to 6 months.

SET ASIDE TIME TO STUDY

Time is the most valuable commodity of the practicing surgeon. Many things compete for your time: learning to manage your practice, preparing for your cases, taking call, building a reputation, finding a spouse and raising a family, and keeping your health and sanity. Setting aside a routine time to study for the boards is helpful. Small amounts of routine time add up. They decrease the need to cram for the boards in the month preceding the test. They decrease the amount of last minute stress and acid buildup.

Taking the boards is a professional activity. Set time aside in your professional calendar for board review. You can spend the time away from your practice for an entire week at a board review course. That will cost you the registration, airfare, and hotel and a week’s time off of work. You can accomplish a similar amount of study without leaving your practice, by setting aside 3 or 4 hours weekly in your schedule. Have your secretary PUT IT ON THE CALENDAR. Come into the office an hour before your staff. Come in on Saturday or Sunday morning. Just don’t try this at the end of the day when you have a pile of paperwork on your desk! Once you establish the study routine and have this time firmly carved into your schedule, you can use it after the boards for reading your journals, doing paperwork, or writing papers.

MAKE YOUR STUDY EFFECTIVE

Some hints you probably know but ignore anyway . . .

– Stop streaming your favorite shows and turn off the television—You can’t watch a football game or movie and actually concentrate on your surgery material. The elective material is inherently easier (and let’s face it, more fun) for your mind to assimilate.

– Turn off your phone and let the voice mail do its job during your study periods.

– Like driving, don’t text while you study.

– Don’t study in bed or on a comfortable couch—the nap will win every time—use your desk or the kitchen table/counter.

– Don’t study with someone else until you are comfortable with what you know and then ask someone else for help—spoon-fed information doesn’t stay with you.

– Learn vicariously—listen to what other people say at meetings, in the hallway and at Morbidity and Mortality Conference (M&M).

STUDY TECHNIQUES

STUDY TECHNIQUES

HOW DO YOU STUDY?

An entire section on learning styles is beyond the scope of a short review session. Suffice it to say that different students learn material differently. Most educators would assume that at the stage of certification for a profession that Adult Learning Styles would be the appropriate techniques. Some of that may be true. I personally have found certification examinations to be more like an old-fashioned carrot and stick. The carrot—if you pass, you’re done for 10 years and the stick—if you don’t pass, it’s another few thousand dollars, agony, and time off of work. We are all inclined to study what we like, what we do and become good at it—that’s what professionals do. Microsurgeons are unlikely to want to study the Tessier classification of facial clefts and the craniofacial surgeons are unlikely to want to study about the effects of the newest anticoagulants on microsurgical flap salvage and complication.

HOW DO YOU PREFER TO LEARN?

For a test such as the qualifying board examination, you just have to study what’s on the list. There are ways to make that easier for yourself. If you spend a little time reflecting on the ways that you learn easily, you can apply the same learning/teaching style to your studying. Layering of information or repeating it helps cement that information in your mind. How to reinforce your reading depends on the individual. Ask yourself honestly how you prefer to learn?

– When you hear material—plan your study schedule around a conference schedule (such as your residents’ conference schedule or a review conference such as this one) so that the presentations will reinforce your reading, also look for things on tape/disk and keep the Walkman/disk player nearby. Also, take advantage of Grand Rounds and conference presentations at the closest plastic surgery residency—most offer an hour of CME credit for free—and someone else can organize the esoteric information for you.

– When you write information—outline the material, even if you never intend to read your notes; writing out information will help and you can use the scrap paper for the birdcage.

– When you get the wrong answer and feel stupid—use review books and do the questions right after your reading; don’t write in the book so you can use it again to refresh your memory just before the test.

– When you verbalize material to other people—take advantage of your surgical assistants and residents—review with them whatever topic you are reviewing in your studies. Quiz them. Explain the answer to them. Draw it out for them. Write little cheat sheets with them. Do this on rounds, in the cafeteria, and in the operating room (OR). It benefits you and it benefits them.

STRATEGIES FOR TAKING MULTIPLE-CHOICE TESTS

STRATEGIES FOR TAKING MULTIPLE-CHOICE TESTS

KNOW THE TEST

The ABPS gives you a very clear description of the test you will take.

The written examination will consist of the following format:

– Fifteen-minute optional tutorial

– Four hundred multiple-choice questions formatted in four blocks of 100 questions. Each block is 1 hour and 40 minutes in length.

– Total break time of 45 minutes (optional)

– Total testing time is 6 hours and 40 minutes. Total time at the test center is no longer than 7 hours and 40 minutes

All candidates will have the same number of questions and the same time allotment. Within each block, candidates may answer questions in any order and review and/or change their answers. When exiting a block, or when time expires, no further review of questions or changing of answers within that block is possible.

Candidates will have 45 minutes of total break time, which may be used to make the transition between blocks and for a break. A break may only be taken between each block of questions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree