Simultaneous breast augmentation and mastopexy is a common procedure often considered to be one of the most difficult cosmetic breast surgeries. One-stage augmentation mastopexy was initially described more than 50 years ago. The challenge lies in the fact that the surgery has multiple opposing goals: to increasing the volume of a breast, enhance the shape, and simultaneously decrease the skin envelope. Successful outcomes in augmentation can be expected with proper planning, technique, and patient education. This article focuses on common indications for simultaneous augmentation mastopexy, techniques for safe and effective combined procedures, challenges of the procedure, and potential complications.

Key points

- •

Identify pertinent anatomy and indications for simultaneous augmentation mastopexy.

- •

Discuss operative strategies for simultaneous augmentation mastopexy.

- •

Identify how to avoid and treat potential complications of simultaneous augmentation mastopexy.

Introduction

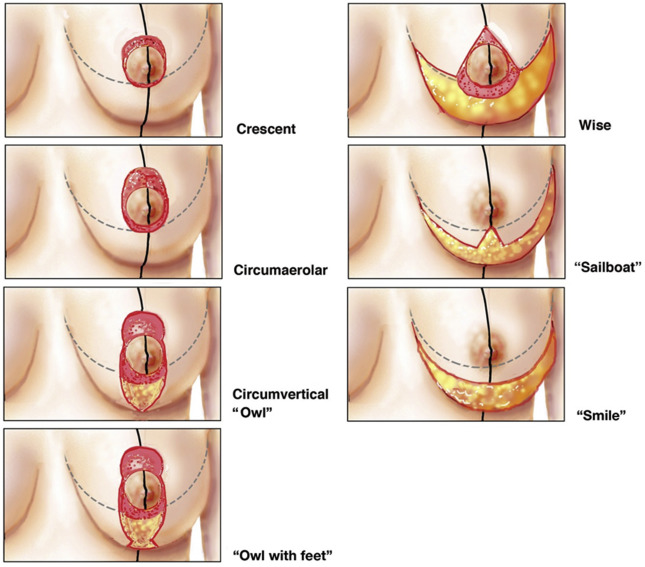

Plastic surgeons have been performing simultaneous breast augmentation with mastopexy for decades. Although staging procedures remains the safest option in certain situations, in many cases these procedures are now being performed together, with excellent results and low complication rates. Proper patient evaluation and tissue-based planning is important, and it is critical to evaluate these patients carefully when planning this challenging procedure. Breast measurements, chest wall contour and breast footprint, breast tissue density, skin laxity, nipple and parenchymal ptosis, and the patient’s expectations must be considered. The goals include creating a pleasing breast shape with symmetry of the breast mound and nipple position, upper breast fullness, tightening of loose skin, and an increase in overall breast size, with longevity of results and a low rate of capsular contracture or other implant complications. Many types of skin incisions can be used: a superior crescent, circumareolar (“donut”), circumvertical (“lollipop” or “owl”), circumvertical with small inframammary fold extension (“owl with feet”), full Wise pattern (“anchor”), an inframammary fold incision only to improve pseudoptosis (“smile”), or an inverted T pattern without circumareolar component if the nipple and areola in good position (“sailboat”) ( Fig. 1 ). Implants can be placed in a variety of tissue planes through mastopexy incisions, including a subpectoral, subglandular, or subfascial placement. Some surgeons may prefer to stage breast augmentation and mastopexy as 2 separate procedures, and this is sometimes the safest option in certain situations. However, these procedures are commonly performed simultaneously, with excellent results and low complication rates.

Introduction

Plastic surgeons have been performing simultaneous breast augmentation with mastopexy for decades. Although staging procedures remains the safest option in certain situations, in many cases these procedures are now being performed together, with excellent results and low complication rates. Proper patient evaluation and tissue-based planning is important, and it is critical to evaluate these patients carefully when planning this challenging procedure. Breast measurements, chest wall contour and breast footprint, breast tissue density, skin laxity, nipple and parenchymal ptosis, and the patient’s expectations must be considered. The goals include creating a pleasing breast shape with symmetry of the breast mound and nipple position, upper breast fullness, tightening of loose skin, and an increase in overall breast size, with longevity of results and a low rate of capsular contracture or other implant complications. Many types of skin incisions can be used: a superior crescent, circumareolar (“donut”), circumvertical (“lollipop” or “owl”), circumvertical with small inframammary fold extension (“owl with feet”), full Wise pattern (“anchor”), an inframammary fold incision only to improve pseudoptosis (“smile”), or an inverted T pattern without circumareolar component if the nipple and areola in good position (“sailboat”) ( Fig. 1 ). Implants can be placed in a variety of tissue planes through mastopexy incisions, including a subpectoral, subglandular, or subfascial placement. Some surgeons may prefer to stage breast augmentation and mastopexy as 2 separate procedures, and this is sometimes the safest option in certain situations. However, these procedures are commonly performed simultaneously, with excellent results and low complication rates.

Breast vascular anatomy

Nipple blood supply is an important consideration in augmentation mastopexy surgery. The effect of implant placement and tissue undermining on the blood supply must be considered. If the implant is placed in the subglandular plane and significant tissue undermining is performed, the blood supply may be severely compromised. Subpectoral placement of the breast implants does not disrupt the musculocutaneous perforators and is less likely to interfere with blood supply. In addition, the placement of large implants in any plane that results in undue tension on the mastopexy closure can cause vascular compromise. In a recent updated review by the authors, the average implant size placed in more than 1100 simultaneous augmentation mastopexies was 323 mL.

There is variability and overlap between sources of blood supply to the breast. The most important arterial sources are the internal mammary (internal thoracic) artery perforators, which are the dominant vessels ( Fig. 2 ). The second to fourth internal mammary perforators are the main blood supply for a superior or superomedial pedicle. The reader is referred to numerous articles for a more in-depth summary the breast vascular anatomy.

Indications for augmentation mastopexy

Patients requiring augmentation mastopexy are often older than those desiring enlargement with implants. Such patients may have lost weight or are postpartum, and the sequelae of increased tissue laxity, parenchyma loss, striae, and nipple ptosis require a mastopexy to create an aesthetic breast shape. Women with Regnault grade 1 ptosis who desire enlargement are frequently treated with breast augmentation alone; however, nipple position alone is often inadequate to determine whether a simultaneous mastopexy would benefit the patient. There is a challenging subset of women who present with “in-between” breasts. These patients may benefit from a dual-plane breast augmentation. Patients who have grade 1, mild grade 2, or grade 4 ptosis in the setting of surrounding skin laxity pose another challenge. Placing an implant without removing excess tissue can result in skin and glandular tissue hanging off the implant. Another example of a challenging situation is women with mild constriction, with a short nipple to inframammary fold (IMF) distance, mild parenchymal herniation into the areola, or both. Patients without obvious significant breast ptosis often do not expect to hear that they may benefit from a breast lift, and may be unwilling to accept any additional scars. In addition, there is a common public perception that larger implants will suffice as a “lift” and that there is no need for additional scars. Patients often benefit from education about the role of breast augmentation and mastopexy, and the rationale for the surgeon’s advice. Patients with significant grade 2 or 3 ptosis require mastopexy in addition to augmentation.

Preoperative preparation

Preoperative planning is essential to a successful outcome with any breast surgery, and in particular for simultaneous augmentation mastopexy. A thorough personal and family breast history should be noted. According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons published guidelines in accordance with the American Board of Internal Medicine, the use of routine mammograms before breast surgery should be avoided. Patients of specific age groups should undergo annual screening mammograms, and additional screening is not necessary unless there are concerning aspects of the patient’s history or physical examination that require further investigation.

Breast measurements including base width, sternal notch to nipple distance, and nipple to IMF distance are helpful when determining the type of mastopexy incision to use, as are the size and shape of implants. The base width is helpful in determining the appropriate range of implants that will fit the patient’s anatomy, as the base width of the implant should not excessively exceed the breast base width. Planning excessively large implants at the same time as a mastopexy may create more postoperative complications, given the opposing forces on the tissues. If there is doubt about vascularity or the patient desires large implants, it may be prudent to stage the procedure. There may be pressure placed on the surgeon to perform simultaneous surgery, given that the public has an expectation of undergoing only 1 procedure, but the pressure of competition should not bias the surgeon’s analysis and consideration for patient safety.

Patient characteristics such as native asymmetry, chest wall contour, amount of subcutaneous fat and breast tissue density, degree of nipple or parenchyma ptosis (ptosis grades can be categorized according to the Regnault classification) ( Fig. 3 ), quality of the skin, any previous breast surgery, and patient expectations must all be considered when planning surgery. The goal is to create an aesthetically pleasing breast contour with an appropriately positioned nipple-areolar complex, upper pole fullness, tightening of the loose skin envelope, breast symmetry, and increased breast volume. Staging procedures is always an option when there is concern about tissue viability and blood supply. The volume of the implant is determined not only by the breast footprint but also by the skin envelope laxity and parenchyma volume. The Tebbett method describes a mathematical approach to determine ideal breast implant shape and volume, and these criteria are useful when planning surgery. Soft-tissue dynamics are important in determining the final outcome and potential complications in breast augmentation surgery. The type of implant shape and profile determines the distribution of fill within the breast. The authors prefer to use silicone implants and avoid saline implants, which lead to deflations, more complaints about implant visibility and palpability, and higher revision rates. Subpectoral implant placement is associated with more postoperative pain in comparison with subglandular placement; however, the incidence of capsular contracture, implant palpability, and excess upper pole fullness is diminished with the muscle coverage of the implant. Mammography is also more accurate with subpectoral placement. Many women who present for augmentation mastopexy have thin, lax skin and tissue, and partial coverage of the implant results more naturally appearing breasts.

Circumareolar mastopexies have higher rates of revisions and patient dissatisfaction, and the authors avoid them unless less than 2 cm of lift is needed without significant skin laxity or striae Some surgeons may successfully use a crescent mastopexy for minimal lifting with augmentation, but the authors rarely find this as useful as a concentric or circumareolar mastopexy in terms of acceptable scarring.

Managing patient expectations and well-documented informed consent are important components of preoperative preparation, as mastopexy surgery is a frequent source of litigation in plastic surgery. Photo-documentation of the patient’s breasts preoperatively is imperative. Patients rarely recognize their own preoperative breast asymmetry and are unaware of the difference in individual native breast and chest shape, an important aspect to point out to the patient before surgery. Many women have strong preferences for nipple position and upper pole fullness versus a more natural upper breast slope, in addition to size. It is important to discuss these issues with the patient preoperatively. Patients who are not counseled preoperatively are often surprised when they note differences in tissue fullness from the upper pole of the breast compared with the lower and lateral part of their breasts. Mild implant palpability or rippling when patients bend over is usually the consequence of having breast implants, particularly in thin patients or those without substantial breast tissue. Weight loss can exacerbate this issue. Patients may consider it a complication when they feel the implant edge laterally if they are not forewarned of this.

The authors find it helpful to remind the patient that no 2 sides of the body are mirror images of each other and that her breasts will never be completely symmetric. It is important to discuss in detail the type and extent of incisions planned so that the patient is not surprised by the resulting scars. It is also important to discuss that breast implants are not designed to be lifetime devices, and that the patient may need additional surgery on her breasts in the future, as well as the Food and Drug Administration recommendation for surveillance of silicone breast implants.

Operative strategy

All augmentation mastopexy patients are marked preoperatively in the standing position. Patients are given a dose of preoperative antibiotics, and lower extremity sequential compression devices are placed. The arms are abducted and wrapped so that the patient can be positioned upright during the procedure. The areola is marked with a 42-mm diameter nipple marker, and the preoperative markings are measured and rechecked. The pocket for the implant is created through the vertical incision, unless a circumareolar incision is planned. The authors’ preference is to use a subpectoral pocket, releasing the inferior and inferomedial fibers of the pectoralis major muscle. Patients with constricted breasts may benefit from subglandular breast implant position to create a more rounded breast, although the authors prefer to use a dual-plane implant placement in this situation with aggressive scoring of the parenchymal bands of the inferior pole ( Fig. 4 ). The position of the implants should be symmetric and in good position at the time of surgery. Meticulous hemostasis is ensured. Implant sizers with tailor tacking of the mastopexy incisions is a useful technique when dealing with breast asymmetry. The pockets are irrigated with triple antibiotic solution or betadine and rinsed, and once the implants are placed the deep tissue is closed completely. The mastopexy markings are then checked, and this portion of the procedure commences. The authors do not routinely use drains with primary augmentation mastopexy.

Borderline Ptosis

Patients with borderline ptosis and expectations of a nipple positioned over the most projecting part of the breast often benefit from a circumareolar mastopexy, as they require less than 2 cm of nipple-areolar complex elevation. A nonabsorbable interlocking wagon-wheel or purse-string suture is placed in the deep dermis with the knot buried deeply to avoid extrusion ( Figs. 5 and 6 ). Caution must be taken to avoid a tight purse-string suture that can cause vascular compromise to the nipple as the areolar skin is pulled taut. There is often mild pleating of the skin that resolves postoperatively. Scar and areolar widening can still occur postoperatively, but the permanent suture (and choosing patients who do not require significant skin excision) helps reduce this consequence. With significant skin excision, the breast can also appear flattened without an aesthetic natural cone shape that results from horizontal tightening. This consequence should be discussed with patients if they insist on avoiding additional scars. If not warned preoperatively, some patients will complain of postoperative “puffiness,” particularly when their body temperature is warm, as the purse-string suture restricts areolar spreading but the underlying tissue expands.

Deflated Ptosis Grades 2 and 3

Patients with ptosis grades 2 and 3 and skin laxity usually require a circumvertical or anchor-type skin excision. The inframammary incision is kept to a minimum, but the authors find that patients do not tolerate skin puckering or dog ears, and the IMF incision seems to be the most acceptable of all mastopexy scars. The implant is placed through the vertical skin and parenchymal incision. This action offsets the plane of tissue healing from the T junction in the healing skin. This type of mastopexy offers the ability to better correct asymmetric nipples, wide breasts, and significant skin laxity. Invariably, the lower pole of the breast will stretch over time, which can lead to pseudoptosis. To accommodate this natural stretching, the inferior pole of the breast is closed with enough tension that it appears slightly flat on profile. Any irregularity of the areola shape is corrected at the time of surgery. A teardrop-shaped areola will not round out postoperatively. Inferior release of the dermis below the areola may be necessary to allow superior movement of the nipple complex without tethering. Appropriate positioning of the nipple over the implant must be planned and checked intraoperatively to avoid nipples that are too high or too low.

Grade 4 Ptosis (Pseudoptosis)

Patients with grade 4 ptosis may have adequate nipple position and areolar size. This rare situation can be treated with only an inverted-T mastopexy, although the authors find that most patients benefit from slight repositioning of the areolas. Mild pseudoptosis can often be corrected with an augmentation alone; however, in the face of heavy pseudoptotic glandular tissue the authors find that a more pleasing breast shape is created by performing a mastopexy to elevate the parenchyma and excise redundant skin ( Fig. 7 ).