The treatment of vascular anomalies of the head and neck typically focuses on restoration of abnormal structures of the soft tissues. However, vascular anomalies can affect the craniofacial skeleton, and osseous reconstruction may be indicated. Osseous involvement occurs as either a primary or secondary phenomenon. In primary osseous involvement, the vascular anomaly expands the bone from within. Secondary osseous involvement occurs when bony hypertrophy develops because of increased flow of the surrounding soft tissue. This article focuses on the management of the osseous deformities associated with vascular anomalies.

The treatment of vascular anomalies of the head and neck typically focuses on restoration of abnormal structures of the soft tissues. However, vascular anomalies can affect the craniofacial skeleton, and osseous reconstruction may be indicated. Osseous involvement occurs as either a primary or secondary phenomenon. In primary osseous involvement, the vascular anomaly expands the bone from within. Secondary osseous involvement occurs when bony hypertrophy develops because of increased blood flow to the lymphatic tissue. This article focuses on the management of the osseous deformities associated with vascular anomalies.

Venous malformations

Venous malformations (VMs) of the bone are extremely rare, accounting for less than 1% of all osseous lesions. The diagnosis is confounded by antiquated clinical and pathologic terminology. Historically, these types of lesions were referred to as intraosseous hemangioma. However, pathologic and molecular evaluations have shown these lesions to be caused by VMs. Most commonly, these VMs affect the zygoma, mandible, maxillary sinus, and the frontal, parietal, and nasal bones.

Patients typically present with distortion of the facial skeleton, which may be associated with hypertrophy of soft tissues and vascular staining of the overlying skin. When no skin changes are present, these patients are often initially presumed to have fibrous dysplasia, particularly when the lesion affects the zygoma or frontal bone.

Evaluation of these patients is performed with a computed tomographic (CT) scan with coronal, sagittal, and 3-dimensional (3D) reconstruction. Radiographic findings that suggest this diagnosis include circumscribed, osteolytic, hivelike lesions with trabeculations. Angiography may be performed to further document the extent of the lesion and better characterize the vascular inflow and outflow.

Patients with VMs of the facial bones often require surgical resection of the lesion. Although reports of sclerotherapy and embolization have been documented, they do not address the expanded abnormal bone and restoration of the facial skeleton. Therefore, wide resection of the lesion is recommended. After resection of these malformations, significant defects in the facial skeleton may occur and should be corrected during the initial surgery, if possible. Depending on the size of the defect, bone grafting or vascularized bone transfer best achieves reconstruction of vital craniofacial bony structures. Three-dimensional models may be useful in anticipating the defect and planning the reconstruction. The ultimate goal is to restore the facial skeleton to make the patient both functionally and aesthetically normal.

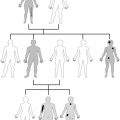

Case 1: VM of Bone

A 4-year-old boy presented with an expanding mass on the left side of his face ( Fig. 1 A). On physical examination, he was found to have a prominent left facial skeleton, soft tissue hypertrophy, and a capillary malformation of the left cheek. A CT scan showed a calcified spiculated mass in the left zygoma (see Fig. 1 B). The mass was excised with adequate margins through coronal and intraoral incisions (see Fig. 1 C). Immediate reconstruction of the left orbit and zygoma with calvarial bone grafts was performed. A lead template was used to create an anatomically correct bone graft that fit perfectly into the orbital and zygomatic defect (see Fig. 1 D, E). The final pathology report found the mass to be a VM of the bone. A postoperative CT scan showed complete excision of the malformation and near-anatomic reconstruction of the left orbitozygomatic complex (see Fig. 1 F). A picture sent by the patient’s family 2 years after surgery displays persistent soft tissue hypertrophy (see Fig. 1 G).

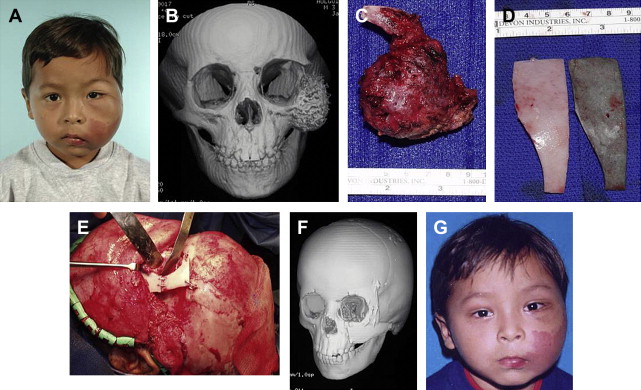

Case 2: VM of Bone

A 27-year-old man presented with what was thought to be a sebaceous cyst close to the temporal hairline on the left forehead ( Fig. 2 A). This lesion was scheduled to be removed as an office procedure, but at the time of excision, the lesion was firm and the cranial bone seemed to be involved. An incisional biopsy was performed, and the pathology report showed VM of the bone. A CT scan showed a left frontal bone lesion extending to the inner table. After 1 month, a resection of the full-thickness calvarial lesion and a split-thickness cranial bone cranioplasty reconstruction was performed (see Fig. 2 B–D). Fig. 2 E shows the patient with a normal forehead contour 6 months after surgery.

Arteriovenous malformations

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are high-flow lesions that can occur in the head and neck region, with the mandible, maxilla, and tongue most frequently involved. These lesions may involve the facial skeleton, and when they do, they may be associated with life-threatening bleeding, particularly after simple procedures such as dental extractions. Intraosseous lesions tend to expand the bone to a point where radiolucency is seen on radiographic examination. Patients may complain of swelling in the jaw, toothache, or acute hemorrhage. A classic finding is periodontal bone loss. The workup of suspected AVMs in the head and neck should include both magnetic resonance imaging and imaging of both the common carotids. Imaging can be done using magnetic resonance angiography, magnetic resonance venography, or conventional angiography. Careful evaluation of these examinations demonstrate the extent of the lesion and the nature of the vascular supply. Suspected bony involvement is best evaluated with CT.

Treatment of soft tissue AVMs usually includes selective embolization followed by surgical resection within 12 to 24 hours. Surgical resection (with or without embolization) has been shown to have a lower recurrence rate and longer time to recurrence compared with embolization alone. In addition, as discussed with VMs, embolization alone does not recontour the abnormal skeleton. Before performing a resection, it is important to share with the patient that the lesion may reexpand after treatment but that the technique offers the best chance for a favorable and sustained outcome. Lesions affecting the bone require wide dissection and resection. Temporary clamping of the external carotids is helpful in controlling what could otherwise be significant bleeding. Smaller vessels in the vicinity of the bone involved can be ligated before resection. Some surgeons recommend a supraperiosteal dissection technique to further limit blood loss. A combination of aggressive electrocoagulation and a generous amount of bone wax or powdered Gelfoam (Pfizer, New York, NY, USA) is usually sufficient to control bleeding after the bony resection is performed. Blood must be available in adequate amounts before the start of the case. Hypotensive anesthesia may be helpful as well. Reconstruction of skeletal structures must be performed when necessary. Small bony defects can be reconstructed easily with calvarial or iliac crest bone grafts. Larger defects may require free tissue transfer.

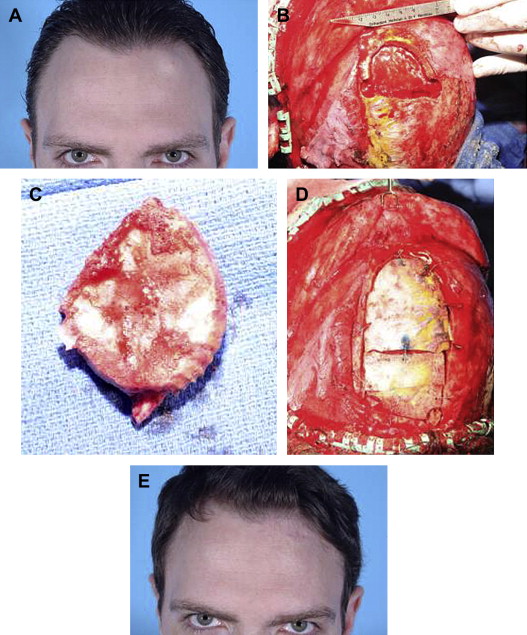

Case 3: AVM

A 20-year-old woman with a high-flow vascular malformation of the left cheek, neck, and lips presented with a history of multiple bleeding episodes from a left mandibular molar. A CT angiogram demonstrated a large AVM in the left cheek and buccal space (see Fig. 3 A–D). Expansion and sclerosis of the left body of the mandible with destruction of the anterior and inferior cortex was noted (see Fig 3 E, F). The patient was taken to the operating room in stages for excision of the AVM, reduction of the mandible, and resection of the left third molar. In order to control bleeding during one surgery, her external carotid was temporarily ligated; the left third mandibular molar was extracted, and the socket packed firmly with Surgice (Ethicon, West Somerville, NJ, USA), which was secured by a tie-over bolster fashion with 0 silk suture. Postoperative pictures reveal improved facial contour (see Fig. 3 G, H).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree