Skin tumours

Vishal Madan MBBS, MD, MRCP

John T Lear MD, MRCP

Introduction

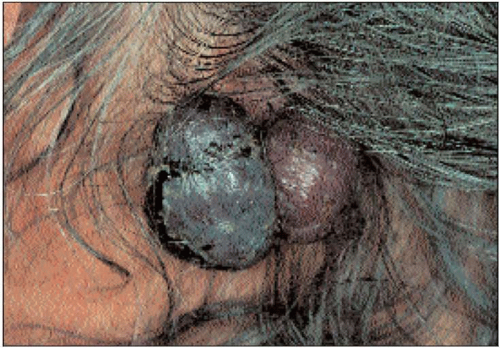

Tumours in the skin can be conveniently divided into benign or malignant. Recognition of which group a particular tumour falls into is paramount. Benign tumours tend to be slow growing, symmetrical lesions (4.1) whereas malignant ones usually grow faster and keep growing and will expand in a haphazard manner, so will often be asymmetrical (4.2). The history and the ABCDE system (Chapter 1) of examining tumours will help in making a diagnosis.

NONMELANOMA SKIN CANCERS

Nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC), which include basal (BCC) and squamous cell cancers (SCC), are the most common human cancers. Because of their relatively low metastatic rate and relatively slow growth, these are frequently underreported. The high prevalence and the frequent occurrence of multiple primary tumours in affected individuals make NMSCs an important but underestimated public health problem.

4.2 Nodular melanoma of the scalp. This was a rapidly growing tumour that was asymmetrical and ulcerating and had a very poor prognosis. |

The recognition of premalignant skin lesions and conditions is important, as early treatment may allow prevention of the malignant process. It may also allow for these lesions and conditions to be followed carefully and any malignancy that develops may be recognized and treated at an early stage. This chapter deals with such premalignant skin lesions and conditions and the tumours that may develop if these are left undiagnosed or untreated.

Actinic (solar) keratosis

Introduction

These are focal areas of abnormal proliferation and differentiation occurring on chronically ultraviolet (UV) irradiated skin, and appear as circumscribed, hyperkeratotic lesions carrying a variable but low (0.025-16%) risk of progression to invasive SCC1. Their presence is an important indicator of excessive UV exposure and increased risk of NMSC.

Risk factors for the development of actinic keratoses include excessive (lifetime) exposure to UV or ionizing radiation, radiant heat or tanning beds in individuals with fair skin, blond hair, and blue eyes, low latitude, working outdoors, light skin, history of sunburn, immunosuppressive therapy for cancers, inflammatory disorders, and organ recipients2.

Clinical presentation

The lesions are asymptomatic papules or macules with a dry, rough, adherent yellow or brownish scaly surface (4.3, 4.4) that are better recognized by palpation than by inspection. Diagnosis is usually made clinically. The lesional size varies from 1 mm to over 2 cm and the usual sites of involvement are the sun-exposed sites such as the face, scalp, and dorsa of hands of middle-aged or elderly patients. Left untreated, these lesions often persist but regression may follow irritation of the individual lesion.

Differential diagnosis

Differentiation from early SCC may sometimes be difficult, especially for smaller lesions. Other differentials include viral warts, seborrhoeic keratoses, and discoid lupus erythematosus.

Management

Sun avoidance and sunscreen use should be advised. For limited numbers of superficial lesions, cryotherapy is the treatment of choice and gives excellent cosmetic results. If the clinical diagnosis is doubtful, larger lesions can be curetted and the specimen can be assessed histopathologically. Excision is usually not required except where diagnostic uncertainty exists.

Topical treatments with 5-fluorouracil cream, diclofenac gel and imiquimod cream3 offer the benefit of treating early lesions and those covering large areas, but with a varying degree of erythema and inflammation. Topical 6-aminolevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy, chemical peels, cryotherapy, and dermabrasion are other techniques used in the treatment of actinic keratoses.

Intraepithelial carcinomas (IEC, Bowen’s disease)

Introduction

Also known as squamous cell carcinoma in situ, these are usually solitary, slowly enlarging erythematous lesions on sun-exposed and nonexposed sites, with a small potential for invasive malignancy. UV irradiation is an important cause, especially in white populations. Arsenic exposure (ingestion of trivalent inorganic arsenic) seems important in the development of lesions in populations consuming contaminated water4. Radiation and viral agents have also been implicated, although a combination of these factors may be involved in some patients.

Clinical presentation

Lower legs of elderly women are most frequently involved. Individual lesions are asymptomatic, discrete, slightly scaly, erythematous plaques with a sharp but irregular or undulating border (4.5). Hyperkeratosis or crust may sometimes form, but ulceration is a marker of development of invasive cancer (4.6). Actinic damage of the surrounding skin is usually present.

Differential diagnosis

Conditions from which Bowen’s disease must be differentiated include lichen simplex, psoriasis, and actinic keratoses.

Management

As with actinic keratoses, the treatment options include destructive measures like curettage and cautery, cryotherapy and surgical excision for larger lesions; delayed wound healing following destructive treatments may be an issue. Topical treatments include 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod. Topical 5-aminolaevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy (ALA-based PDT) is also an established treatment for Bowen’s disease.

4.6 IEC developing features of invasion – ulcerating granulation tissue appearance with hyperkeratosis. |

Cutaneous horn

Introduction

Cutaneous horns (cornu cutaneum) are uncommon lesions consisting of keratotic material resembling that of an animal horn. These may arise from a wide range of benign, premalignant, or malignant epidermal lesions.

Clinical presentation

The diagnosis is made clinically. The lesion is a hard yellow-brown horn that occurs typically in sun-exposed areas, particularly the face, ear, nose, forearms, and dorsum of hands (4.7). Even though over 60% of cutaneous horns are benign, the possibility of skin cancer should always be kept in mind5; inflammation and induration indicate malignant transformation.

Differential diagnosis

The primary diagnosis may be a viral wart, molluscum contagiosum, keratoacanthoma, actinic or seborrhoeic keratosis.

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis

Introduction

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP) is an uncommon autosomal dominant chronic disorder of keratinization, characterized by multiple superficial keratotic lesions surrounded by a slightly raised keratotic border. SCC development within lesions of porokeratosis has been described, as has its association with immunosuppression. Sun exposure and immunosuppression are known triggers to the development of these lesions, which are also inherited as an autosomal dominant trait.

Clinical presentation

The lesions appear on sun-exposed areas as slightly raised keratotic rings, which expand outwards, with the skin within the ring being atrophic and hyperpigmented.

Differential diagnosis

The outward expansion and sharp rim of the lesion distinguish it from other skin lesions (4.8).

Erythroplasia of Queyrat

Introduction

Erythroplasia of Queyrat is a carcinoma in situ that mainly occurs on the glans penis, the prepuce, or the urethral meatus of elderly males. Up to 30% progress to invasive squamous cell carcinoma. The condition usually occurs in fair-skinned individuals but may also occur in dark subjects. Human papilloma virus infection has been implicated. Although histologically indistinguishable from Bowen’s disease, clinically and epidemiologically this is a separate entity.

Clinical presentation

The commonest site of involvement is the glans penis of uncircumcised men, although it may also occur on the shaft or scrotum or vulva in females. The lesion is a solitary, sharply defined, discrete, nontender, erythematous plaque with erosive or slightly scaly surface (see Chapter 7).

Differential diagnosis

Erythroplasia of Queyrat must be differentiated from psoriasis, eczema, lichen planus, Zoon’s balanitis, fixed drug eruption, and extramammary Paget’s disease.

Management

To prevent functional impairment and mutilation of the vital structure, treatment modalities of choice include 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, and microscopically controlled surgery (Moh’s). Progression to invasive SCC is the norm in untreated cases.

Radiation-induced keratoses

Introduction

Chronic diagnostic, therapeutic, or occupational radiation exposure may result in radiodermatitis, radiation-induced keratoses, or radiation-induced malignancy. Ionizing radiation used in the treatment of internal malignancies, cutaneous malignancies, benign skin tumours, or benign inflammatory dermatoses may induce radiation keratoses. The potential for malignant change is proportional to the radiation dose.

Clinical presentation

Chronic radiodermatitis, which usually precedes the development of radiation keratoses, produces cutaneous features similar to those of chronic sun exposure (4.9). Radiation-induced keratosis has morphological and histopathological similarities to actinic keratosis, although elastotic changes and vascular obliteration may be more marked in radiation keratosis.

Management

The available treatment options include curettage, electrodessication, and excision.

Arsenical keratoses

Introduction

These are arsenic-induced corn-like keratoses, most commonly occurring over the palms and soles. The lesions may progress to SCC in 5% or less of the patients. Exposure to arsenicals may be industrial, medicinal, or from consumption of contaminated well water. In addition to arsenic-related skin diseases including keratosis, Bowen’s disease, BCC, and SCC, there is also an increased risk of some internal malignancies.

Clinical presentation

Numerous corn-like areas of hyperkeratosis occur over the palmar and/or plantar skin. In addition to these lesions, patients may have other cutaneous manifestations of chronic arsenicosis, including macular hyperpigmentation, multiple superficial BCC, and Bowen’s disease. Inflammation, induration, rapid growth and ulceration signify malignant transformation.

Differential diagnosis

Viral warts, Darier’s disease, lichen planus, and familial punctate palmar/plantar keratosis may cause diagnostic difficulties.

Management

Keratolytic ointments, cryotherapy, curettage, and oral acitretin have their advocates. Periodic examination for cutaneous or visceral malignancies should be performed.

Basal cell carcinoma

Introduction

This is the most common malignant tumour affecting humans. The low malignant and metastatic potential of this tumour makes it an underestimated health problem, although the associated morbidity can be significant. The incidence of BCC continues to rise and the age of onset has decreased, owing to habits and lifestyles leading to increased sun exposure. The incidence is increasing by ˜10%/year worldwide, indicating that the prevalence of this tumour will soon equal that of all other cancers combined6. Furthermore, 40-50% of patients with one or more lesions will develop at least one more within 5 years.

UV radiation is the major aetiological agent in the pathogenesis of BCC. However, though exposure to UV is essential, its relationship with risk is unclear and epidemiological studies suggest its quantitative effect is modest. Recent studies suggest that intermittent rather than cumulative exposure is more important7. The relationship between tumour site and exposure to UV is also unclear. The distribution of lesions does not correlate well with the area of maximum exposure to UV in that BCCs are common on the eyelids, at the inner canthus, and behind the ear, but uncommon on the back of the hand and forearm. Thus, though exposure to UV is critical, patients develop BCC at sites generally believed to suffer relatively less exposure. The basis of the different susceptibility of skin at different sites to BCC development is not known.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree