Skin infections and infestations

Neill C Hepburn MD, FRCP

Introduction

Skin infections can be divided into bacterial, viral, or fungal whereas infestation will be with either an insect or a worm. The distribution, configuration, and morphology of the rash are important in helping to make the diagnosis but the history, including travel, will also be key. Often dermatitis becomes secondarily infected and can even at times be caused by infection (see Chapters 2 and 3). The use of swabs, tissue culture, histology, mycological studies, and serological tests will often be necessary to make or confirm the diagnosis.

BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

Impetigo

Introduction

A common, highly contagious, bacterial infection with streptococci and/or staphylococci.

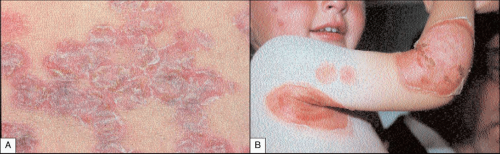

Clinical presentation

Differential diagnosis

Infected eczema may look similar and, of course, those with eczema are predisposed to impetigo.

Management

The lesions should be swabbed to identify the infecting bacterium and its sensitivity. The area should be treated topically with fucidic acid or systemically with flucloxacillin or clarithromycin.

Prognosis

Recurrence is common. Swabs should be taken from the nares of the patient and family members.

Cellulitis

Introduction

Cellulitis and erysipelas are bacterial infections involving the dermis and subcutaneous tissues. Common pathogens are group A streptococci or Staphylococcus aureus in adults and Haemophilus influenzae type B in children. Breaks in the skin such as surgical wounds, abrasions, ulcers, or tinea pedis predispose to cellulitis by providing a portal of entry for the bacteria. Previous episodes of cellulitis, lymph node resections, and radiation therapy, which damage the lymphatics, also predispose to cellulitis.

Clinical presentation

Patients present with sudden onset of malaise and, within a few hours, the skin becomes erythematous, warm, oedematous, and painful. In cellulitis that involves the deeper layer, there is no clear distinction between involved and uninvolved skin. The skin may form bullae, which rupture (9.2). In erysipelas, which tends to involve the more superficial layers and cutaneous lymphatics, there is a clear line of demarcation between involved and uninvolved skin (9.3), and there is prominent streaking of the draining lymphatics.

Differential diagnosis

Secondarily infected eczema is common around leg ulcers but the skin is not warm to the touch. In necrotizing fasciitis, infection of the subcutaneous tissues results in destruction of fat and fascia with pain out of proportion to the clinical signs, and often only a mild fever but with diffuse swelling and pain (9.4). Urgent surgical debridement is needed.

Management

It is usually not possible to identify the infecting organism from blood cultures or skin swabs. Needle aspiration from the subcutaneous tissues and blood cultures can be helpful. Oral phenoxymethyl penicillin and flucloxacillin or erythromycin should be given. In patients who are allergic to penicillin, ciprofloxacin can be used. If the patient is toxic, antibiotics should be given intravenously initially.

Prognosis

Recurrence after antibiotic treatment occurs in about 25% of cases and may be spontaneous or initiated by quite minor trauma. Recurrent cases may require long-term prophylactic treatment with low-dose penicillin or erythromycin.

Pitted keratolysis

Introduction

This is a common superficial bacterial infection occurring on the soles of the feet. It usually occurs in those with sweaty feet, or those who wear occlusive footwear, such as work boots or trainers.

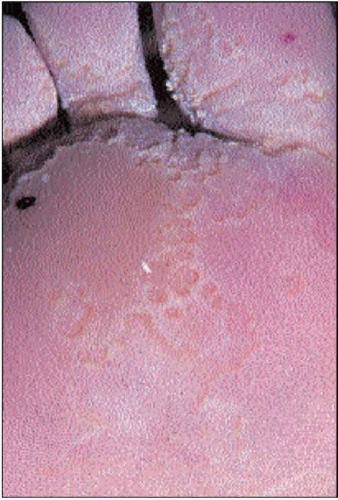

Clinical presentation

The skin over the weight-bearing areas appears moist and oedematous with punched out circular pits and furrows, resembling the surface of the moon (9.5). The feet usually have an offensive smell. Several species of bacteria have been implicated including Corynebacterium, Dermatophilus, and Micrococcus spp. These bacteria excrete enzymes that degrade keratin and thereby produce the characteristic pitted surface.

Differential diagnosis

The appearance (and smell) are characteristic; however, it is sometimes mistaken for a fungal infection.

Management

The bacterial infection responds to topical antibiotics such as fusidic acid cream, or acne medications such as clindamycin solution.

Prognosis

It is important to dry the skin of the feet to prevent recurrences. Options include 20% aluminium chloride (Drichlor) or 10% formaldehyde soaks.

Erythrasma

Introduction

Erythrasma is an indolent skin infection usually of the axillae, groin, or toe webs caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium minutissimum. Hot, humid environmental conditions encourage this infection.

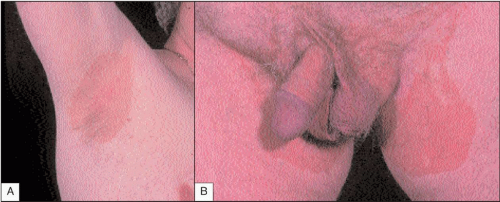

Clinical presentation

There are sharply marginated, reddy-brown patches in the axillae or groin (9.6), which develop often over many years. Sometimes patients complain of irritation but usually they are asymptomatic.

Differential diagnosis

The coral red fluorescence is typical of erythrasma but pityriasis versicolor and tinea infections can have a similar appearance.

Management

Patients respond well to a range of topical antimicrobials such as fusidic acid, miconazole, or erythromycin (oral or topical).

Prognosis

Without treatment the condition persists indefinitely. If treated, it will relapse if climatic conditions are adverse or personal hygiene is poor.

Atypical mycobacterium infection

Introduction

Fish tank, or swimming pool, granuloma is an infection with Mycobacterium marinum – an atypical mycobacterium which grows in culture at 30°C. It is most commonly seen in keepers of tropical fish (the infected fish usually die). It can also be contracted from swimming pools.

Clinical presentation

The lesions usually develop following an abrasion after an incubation period of 2-3 weeks. A nodule develops that may then break down to form an ulcer or remain as a warty plaque (9.7). Lesions are frequently multiple and nodules may form along the line of the draining lymphatics, known as sporotrichoid spread (9.8).

Histopathology

The pathology varies from nonspecific inflammation to well formed tuberculoid granulomas. Intracellular acid-fast bacilli are only identified in 10% of cases.

Differential diagnosis

The main differential in the UK is bacterial pyoderma. In those returning from the tropics, leishmaniasis and sporotrichosis are alternatives as is a tuberculous chancre (9.9).

Management

A skin biopsy should be sent for culture at 30°C but it will take a month for the colonies to grow. Although self-limiting, with spontaneous healing occurring within 6 months, several treatments are advocated, but the optimum treatment has not been established.

Prognosis

Commonly advocated treatment regimens include: minocycline 100-200 mg daily for 6-12 weeks, rifampicin 600 mg and ethambutol 1.2 g daily for 3-6 months, and cotrimoxazole 2-3 tablets twice daily for 6 weeks. Public health authorities should be notified.

9.7 Atypical mycobacterial infection due to M. marinum in a tropical fish keeper, clinically similar to warty tuberculosis. |

Anthrax

Introduction

Anthrax is an extremely rare, but often fatal, infection caused by Bacillus anthracis. It has recently become important because of its use, by terrorists, as a biological weapon. Natural infection occurs after contact with infected animal hides that have usually been imported from Africa or the Indian subcontinent.

Clinical presentation

Patients present with a vesicle or bulla that enlarges over a week or so, to become haemorrhagic and necrotic, leading to the formation of an adherent back eschar (9.10). It is sometimes surrounded by satellite vesicles and is a striking brawny oedema that is surprisingly painless. The lymph glands enlarge and the patient becomes unwell with a low-grade fever.

Histopathology

The bacilli can be seen on Gram staining of the exudate. Culture, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and serology are helpful.

Differential diagnosis

Acute pyoderma is usually painful and the systemic upset is greater in anthrax. Cowpox is very similar in appearance and clinical course but is benign and self-limiting (9.11).