(1)

Department of Plastic Surgery, University Hospital Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands

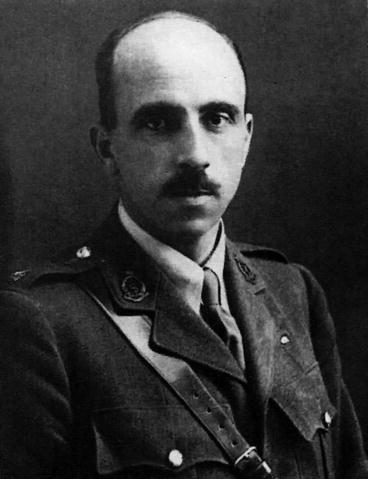

In 1918, as the rumble of the guns died away and peace spread over Europe once again, a new surgical seed, sown in the muddy battlefields of France, was growing slowly towards the light. Out of all the senseless slaughter, pain and grief of war came one good thing at least, and that was plastic surgery. In England, Gillies was the man who nurtured and cultivated the growing specialty and in the post-war years had the courage to commit himself entirely to the practice of this new branch of surgery when others said it was impossible so to make a living. In the beginning, it was Gillies who trod his path alone, but in 1919, he was joined by Kilner, and in the early 1930s, two other New Zealanders, McIndoe and Mowlem, formed the quartet, which subsequently gave the impetus to the dissemination of the principles and possibilities of this new surgical specialty. By the outbreak of the Second World War, it was firmly rooted and has continued to grow in strength and stature.

Whatever is said about the infancy of plastic surgery, Sir Heneage Ogilvie probably best summed up the thoughts of the more perspicacious of Gillies’ contemporaries when he wrote, ‘Gillies invented plastic surgery. There was no plastic surgery before he came. Everything since then no matter whose name be attached to it was started by Gillies’. Now, 54 years after Gillies’ death, one might say that Ogilvie was overstating the case, but there is still no doubt that the debt we owe to Sir Harold is very considerable indeed.

Family Background and Boyhood

For many generations, the Isle of Bute had been the home of Gillies’ ancestors, but his grandfather, opposed to the disestablishment of the Church of Scotland, sailed away to New Zealand in 1852, where he qualified as a solicitor and subsequently became a magistrate in Dunedin, which for the best part of a century was the home of New Zealand’s only medical school. His son Robert, Harold Gillies’ father, married Emily Street, a great-niece of Edward Lear the painter, poet and humorist. Eight children were born to the couple, of whom Harold was the youngest.

Gillies’ father was a successful land agent in Dunedin and sat for one session as a member of parliament. When he died in 1886, he left his wife and children relatively well provided for, and Emily Gillies moved to Auckland. At the tender age of 8, young Harold was taken by his mother to a preparatory school, Lindley Lodge near Rugby, in England. Four years later, he returned to New Zealand and entered Wanganui Collegiate School, also the alma mater of Sir Arthur Porritt, one-time president of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. The school boasted its own golf course, but Gillies was in those days preoccupied with the game of cricket, having become captain of the school eleven and considered by some as the best young player in the country. His brother, Bob, a farmer with whom Gillies often stayed, was an ardent angler, and it was from him that he acquired the rudiments of the art of fly fishing, at which he later so admirably excelled.

University and Hospital Days

Gillies followed two elder brothers to Cambridge University in England, where he had decided to study medicine. Law was the profession chosen by his brothers, but young Harold thought it desirable to expand the family horizons. His baritone voice won him a chapel scholarship, which was withdrawn when it was discovered that he had used the £40 for the purchase of a motorbike, and at this period, he left his mark more upon the sporting than the academic scene. He won a rowing Blue and a Half Blue for golf, at which he represented the university from 1903 to 1905 and whilst still up at varsity reached the semi-finals of the British Amateur Golf Championship.

In those days, Giles, as his friends called him, had already begun to make a name for himself as a practical joker, a foible which to some became an irritating and often exasperating quirk in later years. His habit of fixing his false teeth to walls with chewing gum, his ribald stories told in the then prudish society, a fondness for fanciful disguises, to say nothing of such eccentricities as wearing two neckties or a woman’s hairnet or even make-up, can be ascribed to his dissatisfaction with meaningless convention as well as his zest for fun and life in general.

After Cambridge, he finished his medical studies at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, from which he graduated in 1908. By then, he had also shown a penchant for hard work and was highly thought of by the medical staff. He became a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1910. Following a period as house surgeon to D’Arcy Power at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, he began to climb the hierarchical ladder of ear, nose and throat surgery. In succession, he was chief assistant to Harmer at Barts, Registrar at the Hospital for Diseases of the Throat in Golden Square (of pump fame) and shortly after was appointed private assistant to Sir Milsom Rees.

Anxious to secure a foothold in the fashionable and lucrative sphere of private practice, which centred then, as it still does, on Wimpole and Harley Street, Gillies had hired morning dress for the interview with Rees. Sir Milsom evinced no interest in this sartorial spectacle or the candidate’s qualifications, and Gillies’ disappointment was further compounded when Sir Milsom produced his golf clubs for Gillies to inspect, since the great man was well aware of Gillies’ golfing prowess. A discussion on the game and a demonstration by Sir Milsom of his own techniques were abruptly ended by the arrival of a patient. Almost as an afterthought, Sir Milsom exclaimed, ‘Oh, my dear fellow; I’d forgotten………the job. Well how would five hundred a year suit you?’

So, with this princely offer, began an association that lasted until 1915. Milsom Rees was an influential character, but his practice was rather unconventional, being principally devoted to the care of the voice. He listed among his appointments those of laryngologist to the King and Queen, as well as the royal household, and consultant to the Royal Opera House. It was there, whilst deputising for Sir Milsom, that the famous scissor accident occurred and Gillies was called to attend to a ballerina who had sat upon the offending instrument and ‘injured a part of her body far removed from the larynx’.

With the improvement of his circumstances came marriage to the sister in charge of the new ENT department at Barts. Gillies, as a tolerable violinist, shared a love of music with his new wife, herself an accomplished pianist. Later in life, with their children, they played together as a quartet en famille. This happy marriage lasted until her death in 1957.

The First World War

When the war broke out, Gillies volunteered for the Red Cross, and in 1915, he was sent as a general surgeon to a Belgian ambulance in France. It was about this time that he met Charles Valadier, a flamboyant individual who had obtained a dental degree in Philadelphia. The stout, sandy-haired dentist had established a fashionable practice in Paris and was then touring about in his Rolls Royce, which Gillies said had been fitted out as a mobile dental office, attending to the teeth of the imperial general staff. He was able to convince the generals of a need for a maxillo-facial unit, and one was set up for him in the British Hospital at Wimereux. However, he was only supposed to operate under the supervision of a qualified surgeon, but his work so impressed Gillies that he was moved to investigate the subject further.

It being, as Gillies observed, ‘a rather informal war’, he was able to get hold of a book on jaw and facial injuries by the German, Lindemann. Then, during a period of leave, he decided to visit Morestin at the Val de Grace Hospital in Paris, as it was rumoured that he was performing miracles of surgical reconstruction with skin flaps and cartilage grafts. Morestin, an unpredictable Creole, received him kindly, and as Gillies watched him operate, to use his own words, he ‘fell in love with the work on the spot’.

By the end of 1915, it was decided that Captain Gillies should proceed to the Cambridge Military Hospital at Aldershot to set up a plastic surgery unit. Whilst waiting for his department to be equipped, he revisited Morestin, who declined to admit him to his department! This waiting period was put to good use, however, for with his own money, he bought £10 worth of luggage labels, which he had addressed to himself at Aldershot. These were entrusted to the War Office, with the suggestion that they should be attached to the wounded soldiers who were then to be sent to his unit.

After a few weeks, the labelled patients began to trickle back to Aldershot, and when the Battle of the Somme reached its heights, 2,000 casualties, in place of the 200 expected, arrived in the space of 10 days. This massive influx of ghastly jaw wounds called for close teamwork, and together with a dental surgeon, Kelsey Fry, the unit began to emulate the results which the German surgeons, aided by Esser, were already achieving. There were no sulphonamides or antibiotics in those times, nor were there many standard procedures to follow, for civilian wounds of these dimensions were virtually unheard of.

In 1917, the unit moved to the Queen’s Hospital, Sidcup, in Kent, where Gillies had been largely responsible for planning the hospital so that wards radiated from a covered oval passageway, in whose centre were the operating rooms and dental, X-ray and administrative sections. Here, in the 600 beds available, teams of surgeons from Australia, New Zealand, Canada and, later, America came to observe, learn and treat their own wounded.

The volume of work was enormous, but Gillies’ energy and ingenuity proved equal to the daunting task with which he was confronted. There was no choice but to adopt the famous advice which John Hunter had given Jenner: ‘Why think? Why not carry out the experiment?’ Early on, Gillies, who had originally tried to close facial defects by direct suture or local advancement flaps, realised that where a piece of the puzzle was missing, new tissue had to be imported from elsewhere. It soon became apparent to him too that the lining of cavities such as the nose and mouth was just as important as the outer covering. In all, more than 11,000 major operations had been performed by Gillies and his team by the end of hostilities, and this vast experience had revolutionised the nursing care, the dental and reconstructive surgery and the anaesthetic techniques of that era. This was a grim reminder of the Hippocratic dictum that ‘War is the best school for surgeons’.

Whilst the unit was still located at Aldershot, Gillies discovered that Henry Tonks, a well-known artist and teacher at the Slade School of Fine Arts, was working in the orderly room. Tonks, a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, had turned to art after losing his taste for surgery, and he was soon persuaded by Gillies to become the unit’s artist. His appointment was expeditiously arranged by Sir William Arbuthnot Lane, a surgeon with a weighty reputation, who was the consultant to whom Gillies was answerable. Tonks’ pastels were the basis of the invaluable pictorial records from which Gillies drew so freely to plan and illustrate his work as well as to teach the developing principles. Many of Tonks’ drawings appeared in Gillies’ first book, Plastic Surgery of the Face, and today, a collection of Tonks’ original work is kept at the Royal College of Surgeons in London.

Not all the cases treated by Gillies in those days were gleaned from the French battlefields. In 1916, severely burned naval casualties from the Battle of Jutland were dispatched to him, and he also treated burns in members of the Royal Flying Corps.

This, then, was part of the foundation on which modern plastic surgery has been built, and in England, the men that Gillies attracted formed the nucleus of the specialty which has spread throughout the world along with the early work of continental surgeons such as Morestin, Lexer, Joseph and Esser to name but a few.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree