Chapter 12 Secondary Rhinoplasty

If one considers the number of factors that govern the outcome of rhinoplasty, the frequency with which suboptimal results mandate a secondary procedure is not surprising. Secondary rhinoplasty may be performed to eliminate minor imperfections (revision rhinoplasty) or may include many of the maneuvers routinely used during primary rhinoplasty (secondary rhinoplasty).

Summary

Introduction

Management of the secondary rhinoplasty patient is entirely different from the patient undergoing primary rhinoplasty, presenting a technical challenge and requiring even greater precision in planning and execution of the surgery. Skill is also required to manage the patient emotionally, analytically, and surgically, and to achieve aesthetic and functional objectives.1–5 Both comprehensive knowledge of potential problems and finesse during surgery are necessary to achieve the desired aesthetic goals. The surgeon must clearly understand the patient’s concerns; define the nasal imperfections, and establish realistic goals. In this chapter the manifold differences between primary and secondary rhinoplasties are explored and discussed, including patient evaluation, surgical planning, technical details, and postoperative management.

Patient Assessment and Definition of Nasal Flaws

Many patients seeking information about their first rhinoplasty are unaware of any breathing difficulties and often do not offer complaints of breathing problems. Careful observation often reveals that many of these patients are mouth breathers and internal examination may show significant airway compromise. The reason that these patients deny having breathing difficulty is that they have grown accustomed to obstruction and have no way of knowing how much better their breathing could be. Secondary rhinoplasty patients, on the other hand, are distinctly aware of breathing problems and commonly associate it with previous surgery. These patients have a baseline for airflow with which the change in the airway that occurred after the previous rhinoplasty can be compared. They are keenly aware if functional capacity is not what it used to be. The patient’s airway may have been adversely affected as a consequence of an alteration in internal or external valve function,6,7 formation of scar tissue, medialization of the inferior turbinates and upper lateral cartilages, or any combination thereof.8

Careful assessment of the face may disclose other facial disharmonies relevant to the rhinoplasty that may be contributing to the patient’s dissatisfaction. These abnormalities may include forehead prominence or retrusion, variations of chin deformities,9,10 hypoplasia of the malar bones, and a dysmorphic maxilla or mandible. If these disharmonies go undetected, achieving an optimal outcome is difficult, if not impossible. These features, only if deemed detrimental to the outcome of rhinoplasty, should be brought to the patient’s attention and documented. However, insistence in correcting these flaws as a condition to proceeding with the rhinoplasty should be avoided. It is crucial to ensure that the patient has realistic goals and expectations, and is not suffering from a psychological condition that may result in patient dissatisfaction in spite of a successful technical outcome. Disproportionate concern about the nose form should be analyzed carefully since the incidence of body dysmorphic disorder is higher on this group of patients, as outlined in the primary rhinoplasty chapter. Additionally, recommendations for selection of patients, also profiled previously, should be carefully considered.

Physical Examination

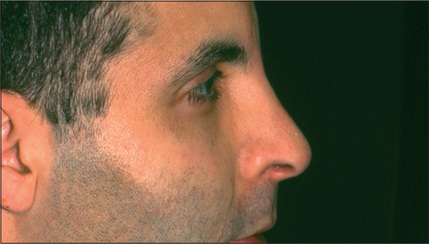

A systematic examination of the external nose starting from the radix and ending at the subnasale, may disclose a variety of imperfections. An under-resected radix, which is a fairly common finding, results in an undesirable transition from the forehead to the nose and is commonly associated with an appropriately lowered dorsum but a fuller than ideal radix (Fig. 12.1). The radix may also be too deep as a result of a preexisting problem that was not corrected or perhaps of under-correction during the initial surgery. Over-reduction of the radix is extremely rare.

Asymmetry or irregularity of the nasal bones is another common cause of concern for the secondary rhinoplasty patient (Fig. 12.2). In an optimal rhinoplasty outcome, there is a graceful transition of shadows from the eyebrows to the tip of the nose. With suboptimal results, these dorsal defining lines are distorted or a second line posterior to the existing dorsal line can be seen, usually indicating a step deformity due to the nasal bone osteotomy being too anterior (Fig. 12.3). Upper lateral cartilages may also appear asymmetric as a result of unilateral over-resection or, more commonly, caused by anterior deviation of the septum (Fig. 12.4). Over-resection at mid-vault may result in an inverted V deformity as a consequence of collapse and medial shifting of the upper lateral cartilage (Fig. 12.5). Increased awareness of this problem and, especially, the use of spreader grafts, have reduced the prevalence of this deformity, although it is still seen fairly commonly. This imperfection is often not noticeable intraoperatively, early postoperatively, or even after up to 1-2 years after surgery. Depending on the thickness of the skin, it may only become discernible several years after surgery.

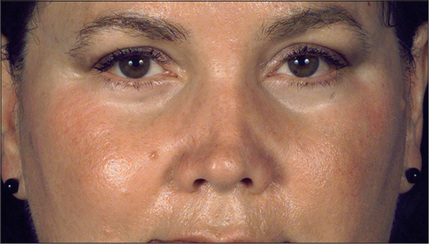

Fig. 12.4 Deviation of anterior septum resulting in appearance of asymmetric upper lateral cartilages.

Abnormalities in the tip area may range from minor imperfections, such as asymmetry of the domes, to gross deformities and complete distortion.11 An under-projected tip is a common feature of noses requiring secondary surgery. Nasal-tip width abnormalities are also prevalent. The alar rims may be retracted or hanging. Disproportionate width of the alar base is a common undesirable finding in noses as well. Supratip deformity may develop as a consequence of inadequate resection of the caudal aspect of the dorsum, but it is more commonly the result of excessive dorsal resection, loss of tip projection during healing, or a combination of factors.12 As stated previously, overresection of the caudal dorsum may result in scar formation and contraction, which ultimately create fullness in the supratip area (Fig. 12.6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree