Scalp Flaps and The Rotation Forehead Flap

E. F. WORTHEN

EDITORIAL COMMENT

Skin expanders are currently quite popular and effective in correcting scalp defects. The principles of flap transfer, as demonstrated in this chapter, are also applicable to expanded skin.

The table of contents for this text reveals a dizzying array of skin flap titles. Names ascribed to flaps over the years have resulted in a confusing adulteration as each designer seeks to single out a particular flap from all the rest. In this preliminary chapter, an attempt is made to define the true distinctions in the nomenclature of skin flaps.

“A flap is a flap is a flap,” as one might well paraphrase Gertrude Stein. All skin flaps share the common feature of a transferable segment of skin with a pedicle of continuing blood supply. Flaps may be local or distant (depending on the proximity of the donor site to the defect), random or axial (a distinct vascular stem is identifiable in the axial as opposed to an anastomosing dermal network in the random), peninsular or island (the skin bridge is preserved over the pedicle in the peninsular). Anatomic location may identify a flap [groin, scapular, transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous (TRAM), and so on]. Imaginative and picturesque names have been used to describe the shape of flaps like clouds in the sky (e.g., banana peel, seagull, pinwheel). Flaps may be designated by ethnic origin (Indian flap); others, perhaps with a thought toward posterity, bear the name of the designer.

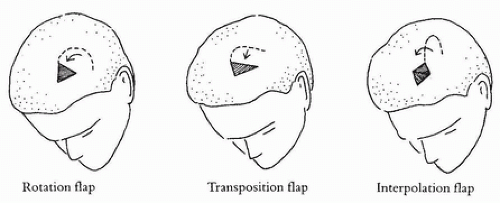

Scalp flaps, whenever possible, should be local flaps because of the singularity of the hair-bearing surface. Massive defects may require the use of distant skin, but a compromised aesthetic result is inevitable. For this reason, the remainder of this chapter is confined to consideration of local flaps (Fig. 1.1). While axial and island flaps may be used for specialized needs, only basic peninsular flaps are discussed.

INDICATIONS

The choice between use of a transposition flap or a rotation flap is most often influenced by the size and nature of the defect. When the defect is large enough, a simple transposition flap ensures the greatest margin of safety because of direct, straight-line flow of the blood supply. A skin graft will be needed to close the flap donor site. When the defect is small and closure of the secondary wound by primary suture is possible, the rotation flap facilitates the adjustment of tension and uneven wound margins.

ANATOMY

A peninsular scalp flap is a segment of cutaneous cover composed of a full thickness of epidermis and dermis with an independent territory of vascularity consisting of a subdermal plexus with afferent arterial supply and efferent venous drainage. The scalp is a unique and specialized integument in which hair shafts penetrate a thick dermis into a highly vascular subcutaneous layer densely bound to a base of flat, rigid aponeurosis. This base, the galea aponeurotica, is the tendinous apparatus through

which the frontalis and occipitalis muscles activate the scalp. This motion is a gliding action of the galea over the underlying pericranium allowed by a gossamer webbing of loose areolar strands in the subaponeurotic layer. This latter plane is essentially avascular, rendering the scalp independent of the pericranium beneath it and thereby facilitating flap transfer.

which the frontalis and occipitalis muscles activate the scalp. This motion is a gliding action of the galea over the underlying pericranium allowed by a gossamer webbing of loose areolar strands in the subaponeurotic layer. This latter plane is essentially avascular, rendering the scalp independent of the pericranium beneath it and thereby facilitating flap transfer.

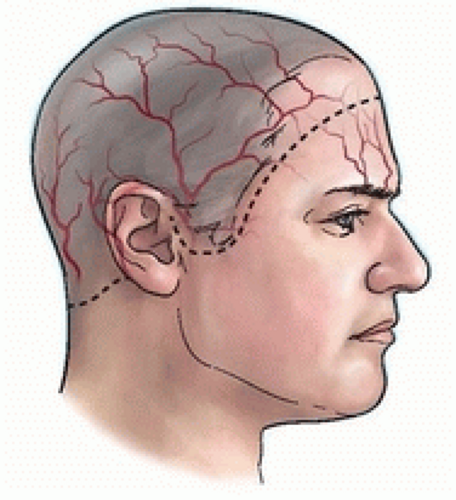

The arteries of the scalp and their accompanying veins originate peripherally and ascend to the dome in bilateral fashion (1) (Fig. 1.2); thus, it is preferable to base scalp flaps peripherally. In the younger patient, there is widespread anastomosis of the end vessels at the vertex, which provides greater latitude of safety in flap design, even permitting retrograde flaps based on this rich vascularity at the vertex. This latter advantage is not enjoyed by the older patient in whom arteriosclerosis diminishes these end vessels. One may surmount even this obstacle by including a large artery in the base of the flap together with delay of the flap. This has been demonstrated with the transfer of postauricular skin on a pedicle extending across the dome to the contralateral superficial temporal vessels (2). Successful microvascular replantation in which the entire scalp and one ear survived on a singular artery and vein reanastomosis has been reported (3, 4).

DESIGN OF THE PENINSULAR FLAP

The forehead and scalp constitute a single anatomic unit differentiated only by the location of the hairline. Preservation of this hairline in a normal configuration is a primary consideration because it creates the frame of the upper face in the frontal and temporal areas. Disruption and asymmetry of this frame are to be avoided.

The rigidity of the scalp does not lend itself to some of the more popular and useful flaps, such as the rhomboid flap, which require plasticity of the surrounding tissue for closure of the donor site. For this reason, one is limited to transposition, interpolation, or rotation flap design (see Fig. 1.1). During the following discussion, one must bear in mind that although geometry offers a worthwhile foundation for understanding basic flap design, it is best replaced with an artistic eye once the basic tenets have been mastered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree