Scalp and nail disorders

Stuart N Cohen BMedSci, MRCP

Introduction

Disorders of the scalp are common and may be intensely symptomatic. Hair loss, in particular, is frequently associated with a high degree of distress. Uncertainty regarding diagnosis makes counselling such patients even more difficult, so accurate diagnosis is especially important.

Although scalp involvement may be a feature of several of the most common inflammatory dermatoses, including psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and seborrhoeic dermatitis, the focus of this section is on diseases with a predilection for the scalp, those that are scalp specific, and on disorders of hair. This latter group often leads to diagnostic difficulty. The value of simple blood tests should not be forgotten, as biochemical abnormalities such as iron deficiency commonly lead to hair loss and are easily correctable.

Many abnormalities of the nail unit result from general skin conditions, most typically psoriasis, but also atopic eczema, lichen planus, and others. In some cases, disease is restricted to the nails. Where the cause of a rash is unclear, specific nail changes may help to confirm the diagnosis. The nails may also give clues to systemic disease, with features of Beau’s lines, leuconychia, yellow nail syndrome, and so on. Unfortunately, many conditions affecting the nail unit are difficult to manage, but care should be taken not to overlook a treatable problem such as onychomycosis.

DISORDERS OF THE SCALP AND HAIR

Alopecia areata

Introduction

This is a nonscarring alopecia with a prevalence of approximately 0.1%. It is associated with other organ-specific autoimmune diseases, such as thyroid disease and vitiligo. Atopy also appears to be linked. In monozygotic twins, a concordance rate of 55% has been found, suggesting that both genetic and environmental factors are relevant.

Clinical presentation

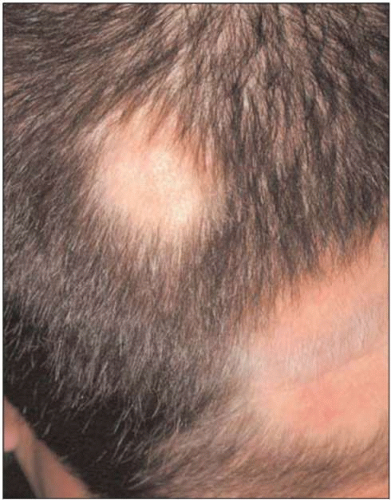

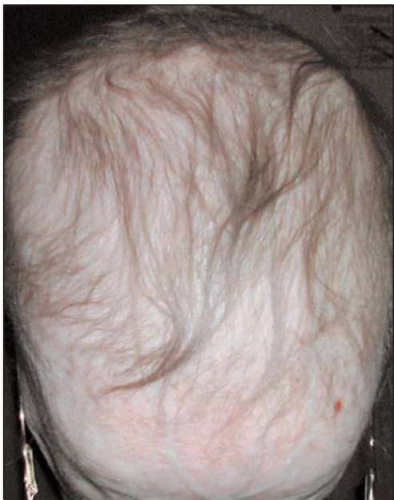

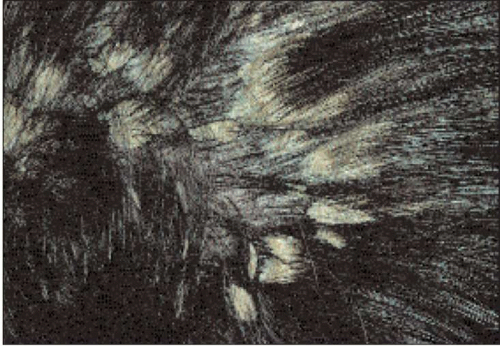

Alopecia areata usually presents with well-defined, circular patches of complete hair loss, with no evidence of scarring (8.1). Exclamation mark hairs (where the proximal shaft is narrower than the distal shaft) are often seen around the periphery of the patches. Other patterns include alopecia totalis (where the scalp is completely bald), alopecia universalis (where all body hair is lost), and ophiasis, in which there is hair loss over the temporo-parietal and occipital scalp. In diffuse alopecia areata, there is widespread thinning, rather than the usual well-defined patches (8.2). Several nail abnormalities may be associated.

Histopathology

A lymphocytic infiltrate is seen in the peribulbar and perivascular areas, the external root sheath, and invading the follicular streamers. Langerhans cells are also present.

Differential diagnosis

Localized hair loss is seen with trichotillomania, tinea capitis, traction alopecia, and pseudopelade of Brocque. History and clinical findings will differentiate the vast

majority of cases. Diffuse alopecia areata is more challenging, as telogen effluvium, iron deficiency-related hair loss, and androgenetic alopecia may look similar.

majority of cases. Diffuse alopecia areata is more challenging, as telogen effluvium, iron deficiency-related hair loss, and androgenetic alopecia may look similar.

Management

If there is doubt about the diagnosis, hair microscopy and serum ferritin may exclude other possibilities. A biopsy is only rarely required. Treatment options include potent or very potent topical steroid applications, or intralesional steroid injection. For more extensive disease, contact sensitization with diphencyprone, PUVA, systemic corticosteroids, and ciclosporin have been used, but response rates are disappointing.

The disease may spontaneously remit, though some patients have regrowth in some areas at the same time as new hair loss in others. Regrowing hairs are often not pigmented. Ophiasis pattern, extensive disease, and associated atopy carry a worse prognosis.

Trichotillomania

Introduction

This is characterized by the plucking of hairs in a habitual manner. It does not necessarily reflect significant psychopathology, though it may be a sign of impulse control disorders, personality disorder, or psychosis.

Clinical presentation

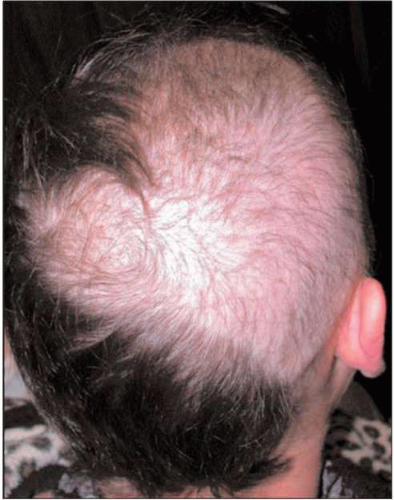

Onset is most commonly in childhood. The scalp is the most common site, resulting in localized or patchy alopecia (8.3). The affected areas tend to have irregular borders and often contain broken hairs of varying lengths. Even in extensive cases, the occiput is usually spared.

Histopathology

Biopsy is rarely needed, though follicular plugging, melanin casts, trichomalacia, haemorrhage, and increased numbers of catagen follicles may be seen.

Differential diagnosis

Alopecia areata and tinea capitis are the main differentials. The former usually results in better defined areas of alopecia.

Management

Diagnosis is usually clinical, though mycological examination of plucked hairs and histology are helpful if there is doubt. Some cases, particularly in childhood, will spontaneously resolve. Treatments have included cognitive behavioural therapy and antidepressants.

Tinea capitis

Introduction

Dermatophyte infection of the scalp occurs frequently in children, but rarely in adults. Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis are the commonest causative organisms.

Clinical presentation

Tinea capitis most commonly presents with discrete patches of alopecia, with or without scaling. Diffuse scaling may occur. Posterior cervical and posterior auricular lymphadenopathy is often present. Alopecia is usually reversed on treatment, but may be permanent after severe or long-standing infection.

An exaggerated host response may result in formation of a kerion (8.4). This is a boggy, purulent plaque with abscess formation and may give rise to systemic upset.

Differential diagnosis

Where scaling is prominent, the condition may mimic seborrhoeic dermatitis or psoriasis (such as in pityriasis amiantacea, 8.5). The alopecia may be mistaken for alopecia areata or trichotillomania. Other causes of scarring alopecia may be considered if scarring is a feature. Kerion is frequently misdiagnosed as bacterial infection.

Management

The diagnosis should be confirmed by mycological studies. Samples may be obtained through skin scrapings and brushings, or from plucked hairs. Microscopy with potassium hydroxide will reveal the fungus, which may be cultured. If the diagnosis is suspected and these tests are negative, fungal staining of a biopsy specimen will identify hyphae or spores.

Tinea capitis always requires systemic therapy. Griseofulvin 10-20 mg/kg/day for 8-12 weeks or terbinafine 62.5 mg daily (10-20 kg), 125 mg daily (20-40 kg), 250 mg daily (>40 kg) may be used. For kerion, in addition to this, antibiotics for superadded infection may be necessary and topical steroids may be used to suppress inflammation.

Folliculitis decalvans

Introduction

This is a form of painful, recurrent, patchy scalp folliculitis, which results in scarring and thus hair loss. It is thought to result from an abnormal response to Staphylococcus aureus toxins.

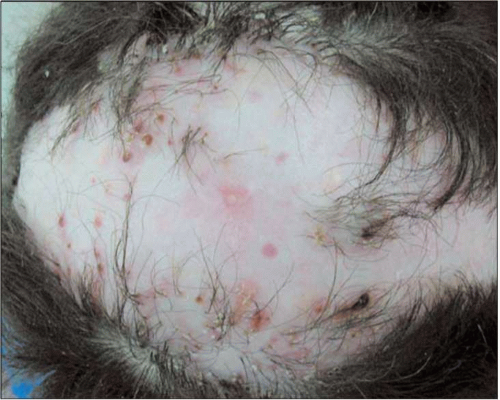

Clinical presentation

There is patchy, scarring alopecia, with crusting and pustules (8.6). There may be tufting of hairs (more than one hair erupting from a single follicle).

Histopathology

Histology shows hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, and perifollicular inflammation.

Differential diagnosis

Other causes of scarring alopecia may look similar, including discoid lupus, lichen planopilaris, or pseudopelade of Brocque.

Management

Treatment options include topical or oral antibiotics, including combination treatment such as clindamycin and rifampicin, or oral isotretinoin. Small areas of scarring alopecia may be excised.

Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp

Introduction

This condition is uncommon, usually affecting young, black men. Follicular hyperkeratosis is thought to represent the primary cause, though bacterial superinfection is frequent.

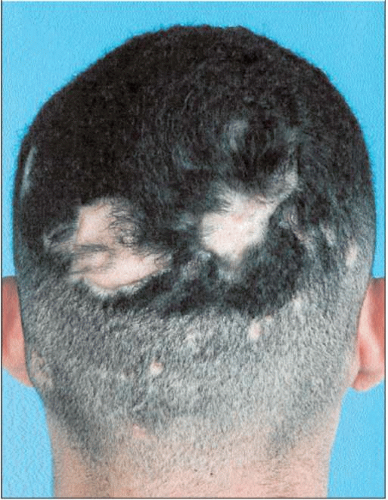

Clinical presentation

Multiple painful inflammatory nodules and fluctuant abscesses occur, giving a ‘boggy’ feel to the affected areas (8.7). It is most common over the occiput. As lesions settle with scarring, alopecia occurs.

Histopathology

Biopsy reveals neutrophilic folliculitis, granulomatous response to keratinous debris, and fibrosis.

Differential diagnosis

In advanced, or burnt-out disease, the boggy feeling may be lost, and the appearance may be similar to other causes of scarring alopecia such as folliculitis decalvans, discoid lupus, and pseudopelade.

Acne keloidalis nuchae

Introduction

This occurs mainly in black men. The precise cause is unclear.

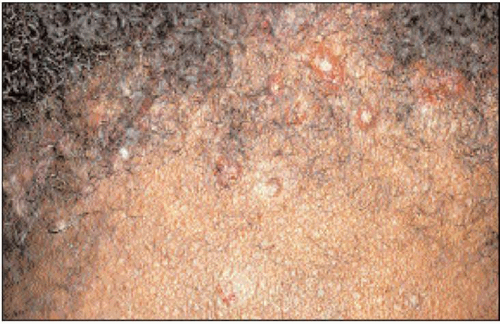

Clinical presentation

It usually begins on the nape of the neck with formation of small follicular papules (8.8). These then become firmer and more numerous, before coalescing into plaques. There is alopecia over the affected area and sometimes tufting of hairs, similar to that in folliculitis decalvans. Advanced disease may be associated with abscesses and sinuses.

Histopathology

Various types of inflammatory infiltrate may be seen, particularly in the upper third of the follicle. Hair fragments with surrounding granulomata may be seen, with scarring. True keloid changes are only seen later.

Differential diagnosis

Lesions may be similar to other types of folliculitis or acne. Advanced disease may mimic folliculitis decalvans, though the site is usually characteristic.

Lichen planopilaris

Clinical presentation

There is patchy hair loss, perifollicular erythema, and scarring alopecia. There may also be evidence of LP at other sites, including nails and mucous membranes (8.9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree