Revision Surgery Following Breast Reduction and Mastopexy

Breast reduction and mastopexy are two commonly performed breast operations in which the surgeon’s goal is the same: to produce symmetric breasts that have a pleasing shape with round, sensate nipple areolar complexes (NACs) that are appropriately positioned. The surgeon attempts to produce breasts whose shape is preserved for as long as possible and that have a minimum number of well-positioned scars.

Both procedures entail a superior shifting of the breast parenchyma with some degree of breast skin flap redraping. However, they differ in that in breast reduction the goal must be achieved in the context of removing breast tissue (often in large amounts) to afford the patient relief of her macromastia-related symptoms, whereas in mastopexy most often little or no breast tissue is removed, and not uncommonly volume is added to the breast in the form of an implant.

Achieving consistently good results in both the primary surgical and reoperative setting entails a thorough analysis of the breast morphology and tissue condition, precisely identifying the correct new nipple position and producing a well-designed and precisely executed operative plan.

These surgical operations are almost always a one-stage procedure in which the surgeon tries to obtain a perfect result with minimal consideration or mention of revisional surgery. However, by their very nature, the results of both procedures are not permanent, and changes in the shape and symmetry of the breasts occur over time. This is related to changes in the relationship of the breast parenchymal volume and overlying skin envelope that are most commonly due to significant fluctuations in weight, pregnancy, and lactation, all of which alter the dynamics of the breast volume-skin envelope relationship. However, additional important factors include the individual patient’s heredity, aging, and the inexorable influence of gravity. Changes in breast shape following breast reduction are common, as is the development of asymmetry, even when a symmetric, well-shaped breast appearance is noted after the original surgery.1

These surgical operations are almost always a one-stage procedure in which the surgeon tries to obtain a perfect result with minimal consideration or mention of revisional surgery. However, by their very nature, the results of both procedures are not permanent, and changes in the shape and symmetry of the breasts occur over time. This is related to changes in the relationship of the breast parenchymal volume and overlying skin envelope that are most commonly due to significant fluctuations in weight, pregnancy, and lactation, all of which alter the dynamics of the breast volume-skin envelope relationship. However, additional important factors include the individual patient’s heredity, aging, and the inexorable influence of gravity. Changes in breast shape following breast reduction are common, as is the development of asymmetry, even when a symmetric, well-shaped breast appearance is noted after the original surgery.1

Reoperative surgery following mastopexy or breast reduction may be sought by the patient and undertaken to address changes in the aesthetic appearance of the breast that occur with the passage of time or to treat complications or problems resulting from the primary operation. Unusual types of reoperative surgery in this setting are sometimes necessary to treat an unexpected intervening problem such as an occult malignancy discovered during initial procedure or to treat recurrent breast enlargement that can occur in the setting of virginal breast hypertrophy.2

As with every type of reoperative surgical procedure, an understanding of the problem and the timing of the surgical intervention are crucial. Whether the surgeon is operating to treat a problem in his or her own patient or in a patient previously operated on elsewhere, taking a careful history and performing a physical examination are required.

Particular attention is paid to the patient’s chief complaint. I need to understand what she is most bothered by. I attempt to have her focus her complaint as much as possible. Is the patient dissatisfied with the scars, changes in shape, contour problems, nipple malposition or frank asymmetry, fat necrosis, or pain in her breasts? Following a previous breast reduction, has there been overreduction or underreduction with the persistence of symptoms? Or, after a mastopexy, has the patient experienced a recurrence of her ptosis, or is she discontented with the loss of upper pole fullness? A key element in successful revision surgery lies in understanding what the patient is most concerned with and what she would like you to do to help her.

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

Another key element is a precise understanding of the previous surgical procedure(s). This goes well beyond recognizing the scar pattern and analyzing breast dimensions and the relationship of the nipple to the breast tissue. It is essential for the surgeon to understand the existing source(s) of blood supply to the NAC. Any surgical procedure on the breast parenchyma not only alters its architecture but very often its blood supply as well. For example, I believe that if a superior pedicle mammoplasty was performed initially, then an attempt to base the blood supply to the NAC using an inferior pedicle design may result in vascular compromise of the NAC and possible nipple necrosis.

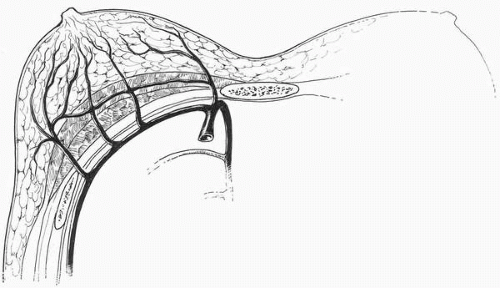

The sources of blood supply to the breast tissue emanate from various pedicle systems3 (Fig. 5-1): the internal and external mammary systems, the thoracoacromial artery with perforators from the pectoralis major muscle (PMM), and the intercostal vessels. An inferior pedicle procedure diminishes the circulation from the internal and external mammary systems, and the surgeon must be aware of this. Because of this I advocate performing revision surgery following both breast reduction and mastopexy by using the same pedicle that was employed during the first procedure. As mentioned in Chapter 2 (see Fig. 2-42) and Chapter 3 (see Fig. 3-10), the presence of an implant in the subglandular position reduces the blood supply from the PMM perforating vessels and sometimes also from both the internal mammary and lateral thoracic systems. This must be borne in mind by the surgeon considering a significant transposition of the NAC at the time of revision of an augmentation mastopexy following a previous subglandular breast augmentation.

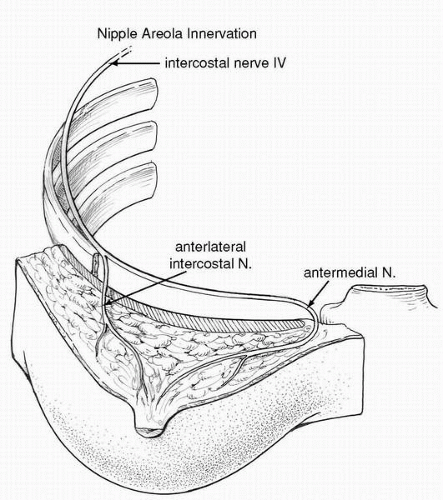

Another pertinent anatomic structure is the sensory nerves to the nipple. Nipple sensation is primarily derived from the fourth medial and lateral intercostal nerve, with the anterolateral branch of the fourth intercostal nerve thought of as playing the key role in providing sensation to the nipple.1,4 Recently my experience with vertical mammoplasty using the medial dermoglandular pedicle has highlighted the significant contribution from the medial branches of the intercostal nerves in terms of their contribution to the sensation of the breast skin and NAC (Fig. 5-2).

Any breast procedure that involves incising through breast parenchyma or a significant resection of the breast tissue adjacent to the central pedicle poses risk to the sensory nerves. Laterally the sensory nerves have their course just on top of the serratus fascia after perforating through the serratus anterior muscle in the midaxillary line.3 Therefore it is important to stay in a plane above the serratus anterior muscle fascia when dissecting in this inferior lateral breast region. As the nerves head in a medial direction they run obliquely and take a superficial course through the breast parenchyma as they proceed toward the nipple. In general these nerves run with small arteries and can be spared in many types of procedures.

PREOPERATIVE EXAMINATION

As previously discussed, the breasts must always be carefully and systematically evaluated in every patient. This includes a detailed visual analysis and thorough palpation.

FIGURE 5-1. Arterial blood supply to the breast. There are major contributions from the internal mammary, the lateral thoracic, the intercostals, and the thoracoacromial system. |

FIGURE 5-2. The nerve supply to the NAC is derived from the medial and lateral braches of the fourth intercostal nerves. |

The visual inspection is performed to evaluate the shape, symmetry, contours, scar location, and skin quality, along with nipple areola shape and position relative to both the inframammary (IM) fold and breast volume in the upright position. Careful notes are made regarding symmetry of contour, nipple areola position, presence of striae, overall skin quality, and position of scars. Additionally, the presence, size, and location of contour deformities are recorded.

I take photographs cropped in a uniform way of all patients using the same background color and lighting conditions. The views taken in each patient are the anteroposterior (AP), each lateral, and each oblique. If there are specific areas of interest in the consultation that may be better highlighted by other views, I will take a photograph from above and perhaps a view from below with the patient lying supine on the examination table.

In addition I record the surface measurements of breast structures from key fixed anatomic points and record these on a worksheet in the patient’s chart. These include the suprasternal notch (SSN) to nipple distance, the breast base width, and the distance of the nipple from the IM fold and from the midline. I refer to both diagrams and photographs when planning all surgical procedures on the breast.

A tactile examination of the breasts includes careful palpation of the skin, scars, and breast parenchyma. Of course careful palpation is done to examine for any masses, areas of thickening, tenderness, and scar adherence. In general, reoperative surgical procedures should not be undertaken until there is a return of mobility to the breast tissue over the underlying chest wall structures, the skin has reacquired its mobility over the breast parenchyma, and the skin scars have begun to soften.

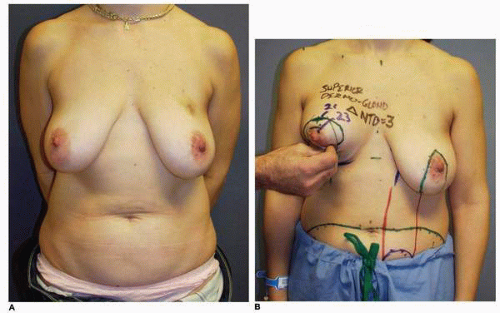

Breast palpation and tactile assessment also provide additional insight into the elasticity of the skin, as well as the volume, distribution, position, and elasticity of the parenchyma. In every patient being evaluated for primary and reoperative mastopexy I simulate the superior transposition of the breast parenchyma by pinching the lower pole or lateral inferior pole of the breast mound. This maneuver (Fig. 5-3A,B) provides additional insight into the parenchymal elasticity and helps me to select the appropriate technique for the mastopexy. The ability to transpose the parenchyma to the upper pole of the breast indicates good tissue elasticity and that the patient is probably a good candidate for a vertical mastopexy. On the other hand, if you are not able to produce this change in breast shape with the maneuver described, a mastopexy with both a vertical and horizontal skin excision should be undertaken. In addition, such a patient should be informed about an increased tendency for recurrent mammary ptosis.

Mammographic examinations of the breasts are ordered as necessary. If a patient seeking a reoperative procedure has not had a mammogram and is near 35 years of age, I routinely order this study, even if the palpation examination of the breasts is normal. This mammogram will serve as the baseline study for future mammograms, and it will provide insight into any mammographic alterations produced by the previous procedures. Surgery on the breast parenchyma produces a change in the breast tissue from the standpoint of intraparenchymal scars that are often discernible on the mammogram. In addition, a patient with high adipose content in her breasts who has had previous surgery may also have calcifications in her breasts. These calcifications are

usually easily distinguishable from the worrisome calcifications that may be associated with mitotic processes in the breast (breast cancers).

usually easily distinguishable from the worrisome calcifications that may be associated with mitotic processes in the breast (breast cancers).

GENERAL COMMENTS REGARDING REOPERATIVE BREAST REDUCTION

It is often stated that breast reduction patients are perhaps the happiest patients in a plastic surgeon’s practice. In the vast majority of instances these procedures result in smaller, shapelier breasts that have a more youthful appearance, albeit with scars on them. The tradeoff that the breast reduction patient makes is “scars for shape.” In my experience these patients gladly make this trade because the resulting smaller breast size allows them to perform virtually all of their activities of daily living more comfortably. In my experience, the overwhelming majority (>95%) of patients demonstrate a relief of their macromastia-related symptoms. This has been borne out in the plastic surgery literature by numerous outcome studies.5,6 It has been my experience that the vast majority of breast reduction patients are happy with their surgical outcome and they both accept and overlook the imperfections resulting from the breast reduction procedure, including asymmetries and associated scar deformities.

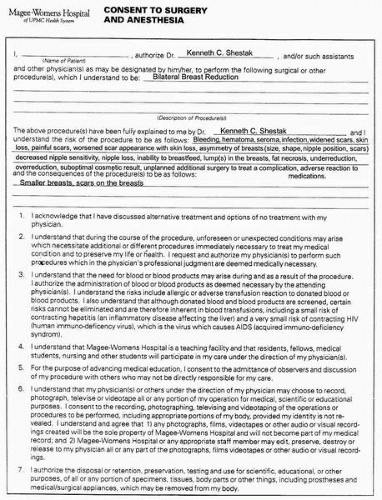

I have found that, although there are numerous complications that can occur following breast reduction, it is rare for the surgeon to perform additional surgery to treat a complication in the acute or subacute phases of wound healing. I often say to patients seen for an initial consultation for macromastia symptoms that complications in breast reduction are not all that common, and when they do occur they usually heal without additional surgery. I still believe that this is true. However, breast reduction remains a highly litigated procedure,7 and therefore it is important for the surgeon to review in detail the immediate and long-term potential risks of the procedure with each patient. I do this by discussing with the patient the risks that are enumerated on a preprinted consent form (Fig. 5-4) that outlines the probable complications and answering any questions the patient may have.

In the setting of reoperative surgery following a previous breast reduction, the initial consultation is longer in duration than it is for other procedures, and follow-up consultations are far more common. I want the patient to understand that the risk of complications is greater than it is in the primary procedure. There may be increased risks for sensory loss in the NAC, increased scar tissue within the breast, and more difficulty maintaining shape. Scars cannot be erased, and skin healing can be less predictable than it is with other procedures. Although improvement in breast appearance is likely, no guarantees can be made. Finally, a brief mention must be made regarding pain following the previous surgery. The etiology of breast pain, or mastodynia, is multifactorial. I strongly believe that it is rarely possible to cure pain with a scalpel. I specifically mention this to patients who present with pain as one of their main complaints by telling them that in no way can I guarantee pain relief with this surgical procedure and that, in fact, there is a chance that the pain could be worse.

In my practice the reoperation rate following breast reduction is very low. Nevertheless, revisional surgical procedures are done in the setting of a previous breast reduction for an aesthetic compromise in breast appearance or to treat problems resulting from the previous surgery.

Classification of the complications of breast reduction and how I handle these complications follows.

HEMATOMA

Hematoma can occur following any surgical procedure. The presenting symptoms are acute swelling; tenderness; asymmetry; ecchymosis; and, most prominently, pain. Pain is the symptom that predominates when a hematoma occurs anywhere in the body.

The incidence of hematoma following breast reduction is low (1% to 2%) despite the extensive infraparenchymal dissection. In our practice the importance of refraining from aspirin products for at least 10 days before surgery is communicated to each patient. The patient’s ingesting even a single aspirin during the week before the procedure will cause me to postpone the procedure.

Drains do not prevent hematoma and are not used in the majority of patients. However, I selectively use drains in patients with large amounts of dense white parenchymal tissue that exhibits a tendency to ooze. When incised this stromal tissue inhibits contraction of the small blood vessels, which results in prolonged oozing. In addition, patients who undergo large resections (>1,000 g) after which the parenchyma may not precisely fit the skin envelope often benefit from the use of a drain.

Large hematomas recognized following surgery should be drained. The most effective way of doing this is by returning the patient to the operating room, opening the incision, and placing a Jackson-Pratt drain (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ). I have found this to be the most reliable method of managing this problem and the most effective and reliable method of managing problems with hematoma (and seroma as well, although with seroma I place a Penrose rather than a Jackson-Pratt drain).

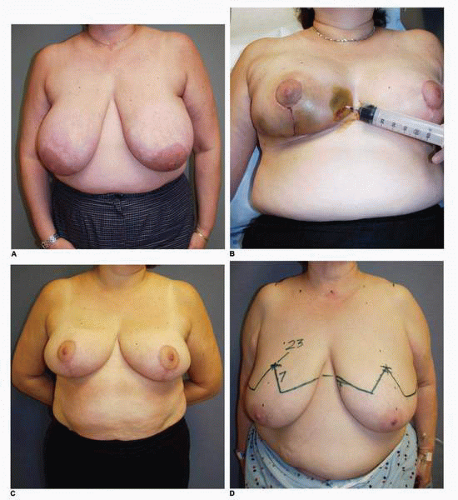

Alternatively, smaller hematomas can be aspirated using an 18-gauge needle following infiltration of the skin with lidocaine (Xylocaine). This method is effective when such collections of blood are noted later in the postoperative period (7 or more days following surgery) when the blood begins to liquefy. I used this technique in this patient, who had an inferior pedicle breast reduction for symptomatic macromastia (Fig. 5-5A). She developed a localized collection of blood in the inferior medial aspect of her breast reduction wound that was aspirated on postoperative day 10 (Fig. 5-5B). Subsequently she healed uneventfully and shows an excellent result at 1 year postoperative without excess firmness or other problem with her right breast (Fig. 5-5C). Aspiration of a hematoma was also used in this patient who had the diagnosis of hematoma made in the lateral aspect of the wound following an inferior pedicle breast reduction (Fig. 5-5D). She had very large breasts preoperatively with a wide chest. Patients with this body habitus invariably have a large fold of tissue extending down from their axillary region that is not part of their breasts (Fig. 5-5E). I routinely tell such patients that I cannot remove this fullness without extending the incision considerably posteriorly. Furthermore, to do so can put the lateral skin flap in jeopardy from the standpoint of its vascular supply because additional vascularity is sacrificed and the length-to-width ratio is increased. However, because this patient was particularly bothered by the fullness, a more aggressive surgical removal of tissue in this area with Mayo scissors was carried out. No drain was placed. She developed a hematoma under the lateral chest flap that was aspirated on postoperative day 7 in the office (Fig. 5-5F). A second aspiration was needed 1 week later to successfully resolve this situation. Not uncommonly more than one aspiration is required. I also have patients apply pressure to such areas with an Ace bandage (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) that is applied and reapplied several times during the course of the day.

TABLE 5-1 Complications of Breast Reduction | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SKIN FLAP ISCHEMIA AND SKIN LOSS

Breast reduction requires careful planning in terms of flap design, surgical precision in terms of flap elevation, and pedicle resection. Enough tissue must be resected from the pedicle such that the wounds are approximated without excess tension in the line of wound closure. When using the Wise pattern with its inverted T incisional closure, the point of maximal tension is at the T junction. This pattern of flap closure involves the development of skin flaps and draping of these around a centrally positioned pedicle. For this reason the sum of the measured lengths of the medial and lateral skin flaps is always longer than the length of the IM incision.

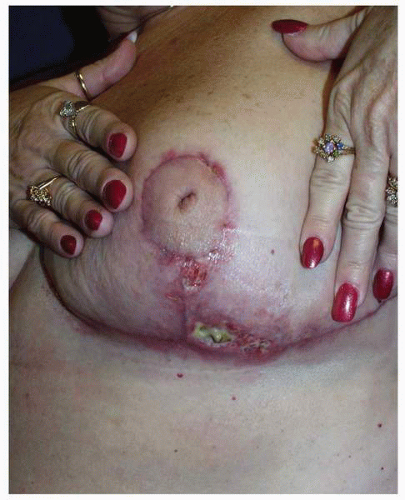

The lateral flap in an inverted T design tends to have a longer length-to-width ratio, i.e., the blood supply is further from the distal edge than it is from the edge of the medial flap. For this reason, the lateral flap is more prone to ischemia at its margin (Fig. 5-6). Such relative skin flap ischemia can result in necrosis and full-thickness skin loss if these flaps are closed under excessive tension.

By the very nature of this flap design (Wise pattern or inverted T) for breast reduction (and in fact for all designs), the skin flaps are sutured with some tightness at the line of closure. However, I do not believe that the skin closure contributes significantly to breast shape. On the contrary, I feel that the key element in this regard is pedicle configuration. I believe that part of the art of breast reduction is that the remaining pedicle must precisely fit the wound created by the flap dissection (Fig. 5-7). Therefore, if there is excessive tension in the line of closure, resection of additional parenchymal tissue from the pedicle should be considered.

Ischemia of the skin flap edges is usually noted early in the postoperative period. It is rarely noted on the operating table. In my experience, ischemia of the skin flap edges following breast reduction is much more common in patients who smoke. This is also true for the complications of delayed wound healing and fat necrosis and should be mentioned to all prospective patients who are smokers.

FIGURE 5-6. The typical appearance of skin loss on the distal margin of the lateral Wise pattern breast reduction skin flap. |

SEROMA

In my experience seroma following breast reduction is rare. It can present as a localized fluid collection that may be apparent as an area of swelling. There may be a fluid wave when the tissue is gently balloted. If such a collection is suspected, it can be aspirated using sterile technique in a fashion similar to that used to treat hematoma. I generally prefer to use an 18-gauge needle. Seromas may require multiple aspirations in most locations of the body. As previously mentioned, an alternate strategy is to open the previous incision and place a Penrose drain in the seroma cavity.

WOUND SEPARATION AND OPEN WOUND FORMATION

Some degree of wound separation is very common following breast reduction. Although I do not have precise data on its incidence, I believe it is in the range of 10% to 15% in patients undergoing inferior pedicle breast reductions and is higher in patients who have vertical pattern reductions. These numbers are much higher in smoking patients, and I inform them of this preoperatively. As previously noted, the most common site for ischemia of the flaps is at the T junction, and this is where open wounds are most commonly noted when the inverted T incisional pattern is used for breast reduction.

Open wounds following a breast reduction or mastopexy will almost always heal in time. Delays in wound healing are most often due to retained foreign bodies in the wound (usually suture material) or to infection. When infection in such wounds is present it must be treated. Depending on presentation, this may require a combination of systemic antibiotics, the topical application of antibiotic ointment, and wound dressing changes.

These wounds heal by the process of epithelialization and contraction. There can be considerable exudation from their surface, making them messy for patients to care for. I commonly ask patients to have patience during the process of wound healing. Simple wound care includes washing the wound in the shower and applying bacitracin ointment topically. The moist environment and local bacteriostatic activity of this topical emollient will facilitate healing. The scars resulting from this secondary healing tend to be larger, usually hypopigmented, thinner in texture, and more depressed relative to the skin surface than the remainder of the scars. However, patients almost never request additional treatment, even when scarring is extensive as is seen in this patient (Fig. 5-8A), who underwent an inferior pedicle breast reduction with the resection of 900 g of tissue from each breast. She developed significant skin loss on each breast (Fig. 5-8B). The total time to complete wound healing was 6 months, during which she was seen frequently in the office so that we could give her the appropriate psychologic support while we performed the necessary wound care. She was indeed a patient patient, and her eventual cosmetic result was satisfactory (Fig. 5-8C,D).

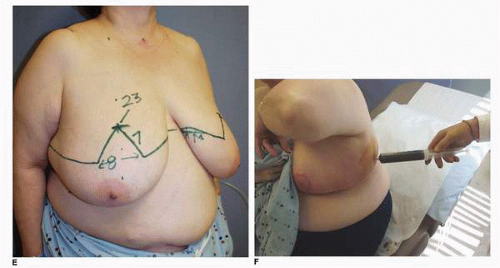

Another example of prolonged healing following skin loss is seen in this 45-year-old patient (Fig. 5-9A) who will undergo a vertical breast reduction using a medial dermoglandular pedicle (Fig. 5-9B). There was excessive tension on the inferior aspect of the vertical skin closure, which resulted in skin necrosis and large open wounds that failed to show any progress toward healing over the first 6 weeks postoperatively (Fig. 5-9C). There were changes on the surface of the granulation tissue suggesting a secondary wound infection, and cultures were consistent with a Staphylococcus sp. She was treated with both mupirocin (Bactroban) topical ointment and oral dicloxacillin [500 mg by mouth (PO) four times daily (q.i.d.)] with rapid epithelialization and wound contraction that led to healing within 1 additional month. She shows a very acceptable appearance of her breasts at 1 year following surgery (Fig. 5-9D,E), and the wound is stable (Fig. 5-9F).

This patient is interesting from several perspectives. During vertical mammoplasty the tension in the line of closure should be on the parenchyma, not the skin edges. It is a parenchymal reshaping procedure, and I made an error in placing too much tension on the skin wound closure.8, 9 and 10 In addition, it is important to recognize when a wound fails to show normal progress toward healing. The most common etiologies are wound infection or the presence of a foreign body, which in this setting is most often a contaminated suture.

In general the wounds resulting from skin loss after a breast reduction progress relatively quickly toward complete healing. It is almost never necessary for the surgeon to perform additional surgery to promote healing of such wounds. In the well over 1,000 breast reductions I have performed, I have had to resort to a split-thickness skin graft only once. This was in a patient who was mentally incapable of complying with the wound care regimen necessary to achieve complete wound healing. Likewise, wound excision and reclosure is almost never an option because the wound is usually indurated and will not hold sutures well, especially if there is any tension at the site of wound edge closure.

The one exception to this may be an open wound secondary to wound dehiscence that occurs at the time of suture removal. In this situation immediate resuturing after infection of a local anesthetic agent can prevent a more prolonged course of healing for this wound. I reoperated on one patient who developed a prolapse of her inferior central breast area through an area of skin necrosis at 1 year following surgery.

CELLULITIS

Infection following breast reduction is very uncommon. Most series will reflect an incidence of 1% to 2%. This is interesting given the length of time that wounds are open and the magnitude of the dissection carried out during breast reduction. The breast is endowed with a robust blood supply, and there are probably other local immunologic mechanisms that are protective against and minimize the incidence of infection.

When infections occur following a breast reduction they usually present as a cellulitis. In such cases there is almost always an open wound that is the portal of entry. The most common causative microbial organisms are Streptococcus sp. and Staphylococcus aureus. Typically the patient presents with erythema; tenderness at the site of infection; and, if the process is significant enough, fever. In cases of pronounced cellulitis the patient may present with shaking chills.

The treatment is prompt institution of appropriate antibiotic therapy. For small areas of involvement diagnosed early, oral antibiotics may be sufficient. I usually begin with cephalexin [(Keflex) 500 mg PO q.i.d.]. If patients are penicillin allergic I substitute ciprofloxacin [750 mg PO two times daily (b.i.d.)]. If the process is more advanced I usually begin parenteral antibiotic therapy using a second-generation cephalosporin [cefazolin (Ancef) 1 g intravenous (IV) q8h]. If the patient has a penicillin allergy I prescribe ampicillin [(Unasyn) 3 g IV q6h].

If an open wound is part of this picture a culture of the wound is obtained by swabbing the surface or unroofing an eschar. This specimen is processed for aerobic and anaerobic organisms. At times obtaining such cultures may help the clinician readjust the antibiotic treatment regimen.

In every case it is important to monitor the result of the infection process. Toward this end the patient is checked on a 24-hour basis and rechecked daily. An improvement in the cellulitis is expected within 48 hours of treatment. The average duration of therapy is between 7 and 10 days.

RECURRENT CELLULITIS

A significant cellulitis that recurs may suggest a number of potential etiologies, including a retained foreign body (usually suture material), a scar that has become embedded beneath the surface or a scar that is unstable and prone to small cracks that may become portals of re-entry, an infected hematoma or occult abscess, and fat necrosis with associated infection. Additional alternative diagnoses are hidradenitis suppurativa of the breast or an immunocompromised host.

Such clinical presentations may merit a workup with a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan to rule out a retained foreign body, retained fluid collection, fat necrosis, or a foreign body. Appropriate additional therapy is then undertaken as needed depending on the breast imaging findings and ancillary diagnoses.

Recurrent cellulitis of the breast often presents a challenge. It is important for the surgeon to make a diagnosis regarding the etiology and to refrain from surgical overtreatment. Consultations with the infectious disease service or other surgical colleagues with special training in the area of wound healing may be helpful. There is probably little indication for long-term suppressive antibiotic therapy.

NIPPLE AREOLAR ISCHEMIA

Ischemia of the NAC is a dreaded potential complication of every predicted breast reduction procedure. It is most often related to arterial insufficiency and it usually occurs in the setting of a large reduction where a long pedicle is used to carry the circulation to the NAC. In such situations the tissue resection compromises the arterial perfusion of the nipple and surrounding areola. In addition, there may be a component of venous insufficiency in those cases where the pedicle is excessively folded during wound closure.

The latter situation presents with a hyperemic congested appearance of the NAC, which shows dark deoxygenated blood emanating from its cut edges. In the former condition of arterial ischemia the nipple and areolar tissue appears pale and dusky and there is little or no blood entering its substance or noted at the cut edges of the areola.

Nipple areolar necrosis in the setting of breast reduction is very uncommon, occurring with a frequency of 1% to 2%. It is probably much rarer following mastopexy. Predisposing factors at the time of the primary surgery include a lengthy pedicle (in an inferior pedicle reduction a distance of greater than 15 cm from the nipple to the IM fold), a nipple transposition distance exceeding 18 cm, and extremely large reductions (>2,000 g) done with pedicle techniques where resection of the parenchyma can cause a decrease in nipple blood supply due to excessive folding at the time of closure.

In the setting of reoperative surgery this problem may result from an incomplete or inaccurate understanding of the previous pedicle orientation or blood supply used during the initial surgery. I have previously alluded to the importance of obtaining the most accurate information about the techniques used during previous procedures when reoperating on a patient who has had a previous breast reduction or mastopexy. When the surgeon cannot obtain such information and nipple relocation is planned, it is best to maintain a broad central pedicle as the source of blood supply to the NAC. Finally, cases of a previous subglandular breast augmentation may pose a real problem in maintaining blood supply to the nipple when a significant nipple transposition distance is planned.

Nipple areolar necrosis is a small but real possibility in every mammoplasty procedure, including reoperative procedures. As such it must be a part of the informed consent for the patient who is considering these operations.

It is important for the surgeon to recognize nipple areolar ischemia on the operating table. However, this is not always easy to do, especially when operating on dark-skinned patients of African descent or others with dark areolar skin. If there is concern about the color changes in the areola or about capillary refill following pressure placed with a finger or surgical instrument, abrading the edge of the incision with a gauze sponge and examining the quality of the bleeding may be helpful. In some situations the administration of IV fluorescein (Chapter 8) might be of benefit.

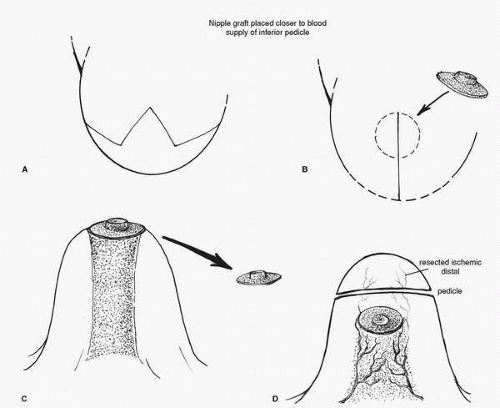

If real concern about nipple ischemia exists during wound closure, the wound should be opened and the pedicle checked for any evidence of folding or kinking. I prefer to place warm saline-soaked sponges on the pedicle to try to reverse any vasospasm that might be present. If there is obvious ischemia of the nipple following these maneuvers surgical treatment is undertaken. The nipple should be removed from its position on the pedicle by excising it as a full-thickness skin graft (Fig. 5-10A). It is prepared by aggressively defatting the areola and resecting the tissue on the undersurface to the level of the superficial dermis. I prefer to leave some of the nipple elements (the ductal tissue) in place so that when the nipple areolar graft heals, there will be some degree of nipple projection. The ischemic portion (distal aspect) of the pedicle is usually resected at this point to minimize the chance of fat necrosis and to more easily accommodate breast skin flap redraping. The free graft of the NAC is then placed on the de-epithelialized skin flaps if an inverted V pattern has been used to develop the skin flaps (Fig. 5-10B), or on a de-epithelialized portion of the original breast pedicle closer to the origin of its blood supply (Fig. 5-10C). If a Wise pattern design has been employed for the original skin incisions and the areolar cutout has been made, it is

closed with a purse string suture technique and the area where the nipple should be placed is de-epithelialized (Fig. 5-10D). Alternatively, the previous areolar cutout can be closed as a linear scar creating a T; however, the extent of the horizontal incision should not fall outside of the periphery of the nipple areolar graft. The graft is then secured by placing sutures at its periphery and finally by constructing a tie over bolster-type dressing. In my experience this gives the frankly ischemic NAC noted at the time of the original surgery the best chance for survival.

closed with a purse string suture technique and the area where the nipple should be placed is de-epithelialized (Fig. 5-10D). Alternatively, the previous areolar cutout can be closed as a linear scar creating a T; however, the extent of the horizontal incision should not fall outside of the periphery of the nipple areolar graft. The graft is then secured by placing sutures at its periphery and finally by constructing a tie over bolster-type dressing. In my experience this gives the frankly ischemic NAC noted at the time of the original surgery the best chance for survival.

FIGURE 5-10. A, The treatment of frank nipple ischemia recognized at surgery requires that the nipple be removed as a full-thickness graft. B,

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|